The Legend of Maula Jatt has done a lot of unprecedented things: an ambitious concept, a massive budget, record-shattering revenues, and gripping execution. But perhaps its most iconic battle will not be Maula Jatt vs Noori Nuth on screen. It will be the off-screen faceoff between the producers and exhibitors – a power play that has sought to upend a jealously guarded formula governing the business of movies.

Put simply, the producers believed they had an unprecedented product, and they wanted an unprecedented payday. So they proposed to rewrite a settled financial sharing formula with exhibitors. They did this by proposing two new formulas, which, in short, sought higher ticket prices for the first 11 days, and a bigger share of the receipts. The non-financial demands in these formulas also mirrored swashbuckling action sequences of a reborn Maula Jatt.

Here is how it all went down.

The beginning

Word of a return of Pakistan’s most well known action franchise first came into the open back in 2013, when another action-epic film Waar was released. Waar was also a first of its kind production back then. The director of that movie was Bilal Lashari, who spoke about his next project: a film that would bring the Punjabi gandasa genre back onto the screens in the modern age. And so the return of the brooding son of Sardar Jatt was conceived.

Maula Jatt, just for background, is a uber-masculine, testosterone-driven Punjabi action hero/anti-hero who first appeared on screen in 1979. The movie and its characters were based loosely on a novelette by Ahmed Nadeem Qasimi called “Gandaasa”, says critic and journalist Rafay Mahmood.

Jatt’s oft-exaggerated machismo has since been beloved by the masses, so much so that it inspired spin-offs and derivatives and deeply impacted the Pakistani cinema industry. Jatt was most famously and iconically played by the unmatched Sultan Rahi, who delivered one-liners that found place in Pakistani lore.

“Maula nu Maula na maare, te Maula nai marda.” Wow.

So when word came out that Lashari was taking this on, expectations began to rise. It took 10 years for Jatt’s re-invention (it’s not a “remake” Lashari insists) to be completed and for the project to see the light of day, producers say.

It’s here and it’s huge

Closer to the completion, it was clear that it was going to be big. Lashari says in interviews that he did nothing else during the shooting or production of the movie. Sources say it ended up costing between Rs 400 to 500 million and this doesn’t include the marketing budget.

Nadeem Mandviwala, owner of Karachi’s Atrium cinema and also distributor of the movie, says he has seen nothing like it in all his years in Pakistan. According to him, nobody could have believed that such a movie could be made locally. In a press conference held in Karachi on October 21 he said the issue was how to maximise returns with such few cinemas in Pakistan. The movie is being shown on more screens abroad than in Pakistan – but more on that later. Huge amounts of money were put into making Maula Jatt, and into advertising it.

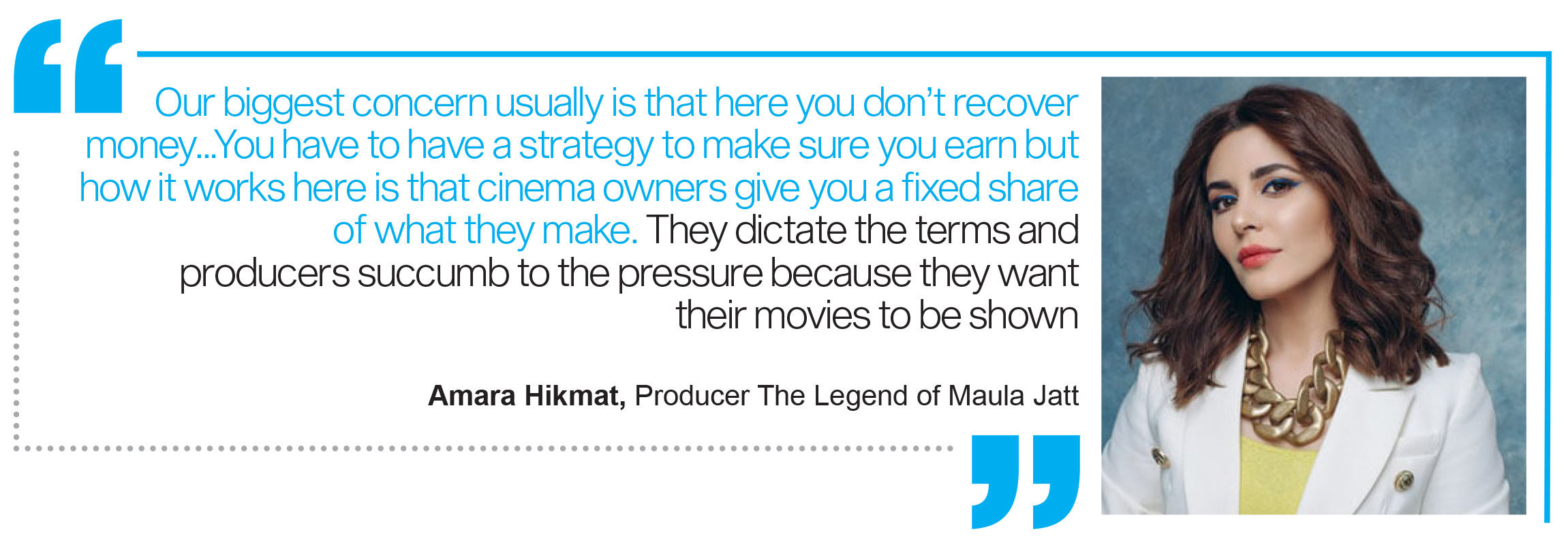

Ammara Hikmat, producer of Maula Jatt also mentioned how much time and money went into pulling off this feat. “So many expenses that normal Pakistani productions don’t incur, caused this huge budget. From foreign crew to production spread over two and a half years in outdoors and legal battles, everything was quite costly.“

Hikmat also added that both she and Bilal made a conscious decision to not spend on fancy premiers, promos and road shows. Instead, they decided to take the digital route. “We advertised in the last two weeks. We used the trailer to generate hype, and abroad we advertised on buses, metros and tube stations.” All this paid off, she added. So while their release in Pakistan may have been a little disappointing, the response overseas was both mind-blowing and gratifying.

“We have used the best of everything despite all obstacles,” she said. “We opened on fewer screens as per our overseas distributor’s suggestion, allowing demand to determine profits.” With every passing day, screens had to be added in Pakistan and abroad. “People were travelling all the way from Murree to Lahore to watch the movie.” It worked for us because the process of word of mouth was great and people loved the content. According to Hikmat, Lashari had the foresight to know that his product was nothing anyone has experienced in Pakistan. Echoing Mandviwala’s words she said, “he knew that his work would speak for itself, people just had to see it.”

Mahmood agrees. “It is the first time in history that the exhibitors’ share doesn’t matter.”

The face off

With so much money spent on making the film, a strategy had to be put in place that would benefit the producers while not hurting anyone else in the business chain. So they proposed two new financial formulas.

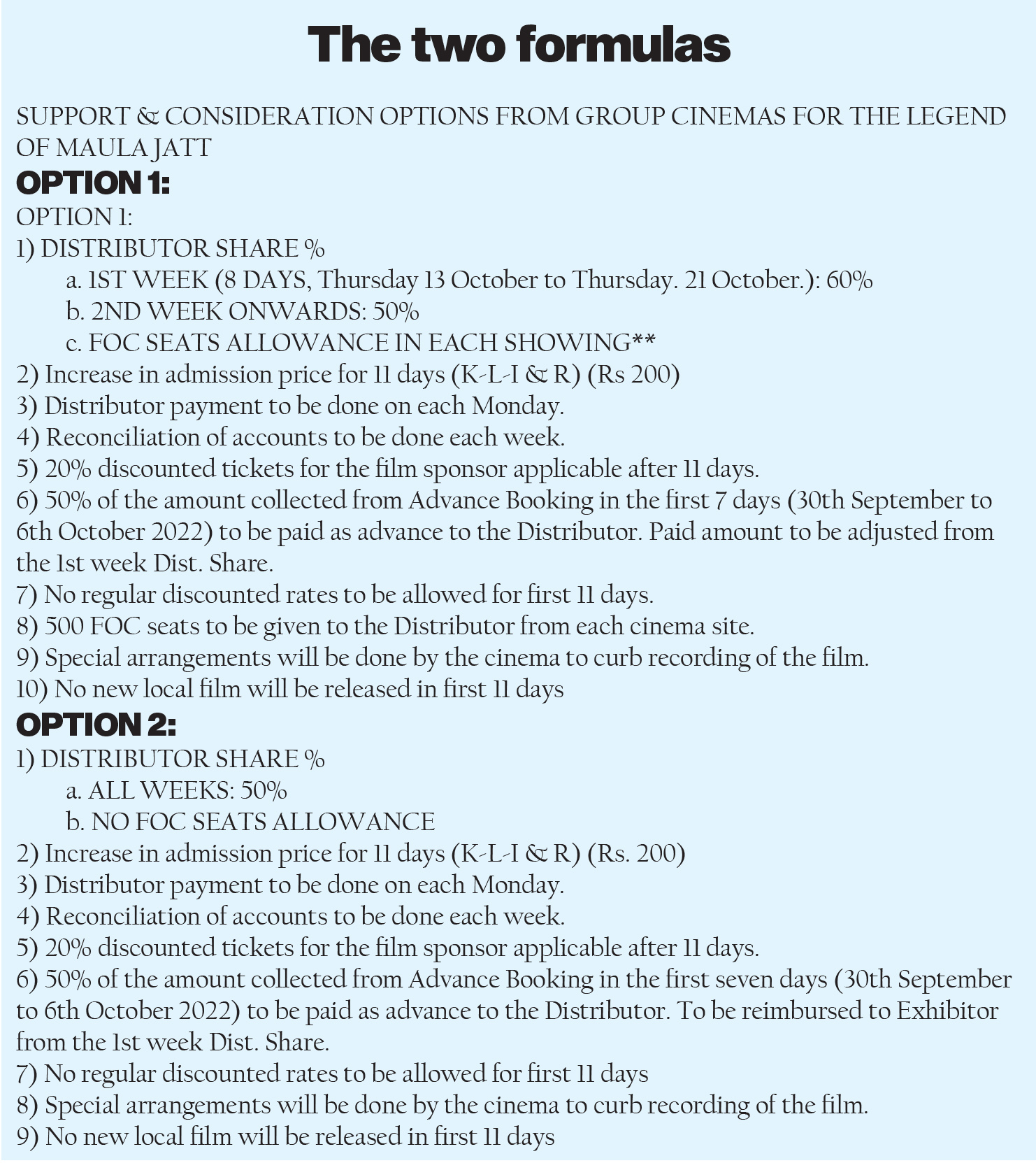

According to details given in a press conference, the first formula proposed said the distributor share for the first eight days – October 13 to October 21 – would be 60%. That was the highest ever demanded from exhibitors. This would move back to 50% in the second week of the film. To make up for this, they proposed that the ticket price be Rs 200 higher for the first 11 days, so the exhibitor’s absolute share would not be hurt, and would, in fact, increase – or so Mandviwalla believed.

Along with this, there were a number of other demands, such as strict receipt reconciliation timelines, curbing discounted rates and no new local film being released in the first 11 days.

The second formula saw a 50-50 share but demanded no allowance for “FOC” or free of charge seats – which make up a sizeable chunk of cinema footfall.

Mandviwala said that the unusual financial formula was necessary because there was no other option. Abroad, for example in the US, the number of a larger film could be shown on would just be increased and those numbers would be in the thousands. Pakistan, however, does not have this privilege; there are only 60 cinemas and a total of 144 screens, which means there is no economies of scale.

“Our biggest concern usually is that here you don’t recover money,” said Hikmat, justifying their need to recover costs. “You have to have a strategy to make sure you earn but how it works here is that cinema owners give you a fixed share of what they make. They dictate the terms and producers succumb to the pressure because they want their movies to be shown.” For the first time now, producers took the reins. “You have to let them recoup their investments,” she explained, “it is a business after all.”

“For the first time in history, content is dictating the terms,” added Mahmood. But of course, it wasn’t received well by many exhibitors. Listed below are the two options that were given to cinema owners to choose from.

Some exhibitors grudgingly chose option one, while others opted for the second. Some 38 cinema owners agreed, and four did not, Mandviwalla said. Importantly, of the four who walked away, three are considered the ‘big cinema’ owners.

Mandviwala remained unfazed. He said that it is a business at the end of the day. With a slight shrug of his shoulders and sideways tilt of the head he said, every businessman has the right to run his business the way he wants to… “But it was my duty to explain to them why this (new formula of ticket pricing) was important for the producers, for their recovery and their advertising budget.”

This has been a big blow to the business of the exhibitors who walked away, sources within the industry say. But obviously, it would also mean less receipts for the producers given the size of the cinemas. When questioned about this Mandviwala agreed and said he wasn’t worried. “People will continue going to see the movie days and weeks from now, cinema owners have only hurt themselves.”

When asked about who has lost most in terms of business by not showing Maula Jatt in the first 11 days of its release, Hikmat paused. “I would say the exhibitors mostly,” she then answers, almost reluctantly. “I never spoke to cinema owners directly. We partnered with Geo films and later on got Nadeem Mandviwalla on board as the distributor. Nobody knows cinema as good as him in Pakistan and nobody can match Geo’s strategic partnerships. Pre-covid, Mr. Mir Ibrahim had already taken ownership of the project and Geo gave us support not only on air but at the back end as well.

Cinema owners were not easy to interview. “Pakistani cinemas work like a cartel,” said Mahmood. The owner of Nueplex Cinema in Karachi, Mirza Jamil Baig, despite several attempts by Profit was unable to coordinate a time for an interview while others seemed unwilling to answer any questions. One CEO of a cinema in Lahore, wanting to remain anonymous, said the rules put forward by the distributor were “ridiculous”. “If it is a business for them, it is a business for us, too. Why should we not have a say in the matter?”

This is disheartening for some like Hikmat who was hoping the industry would come together for a movie of this scale and scope.

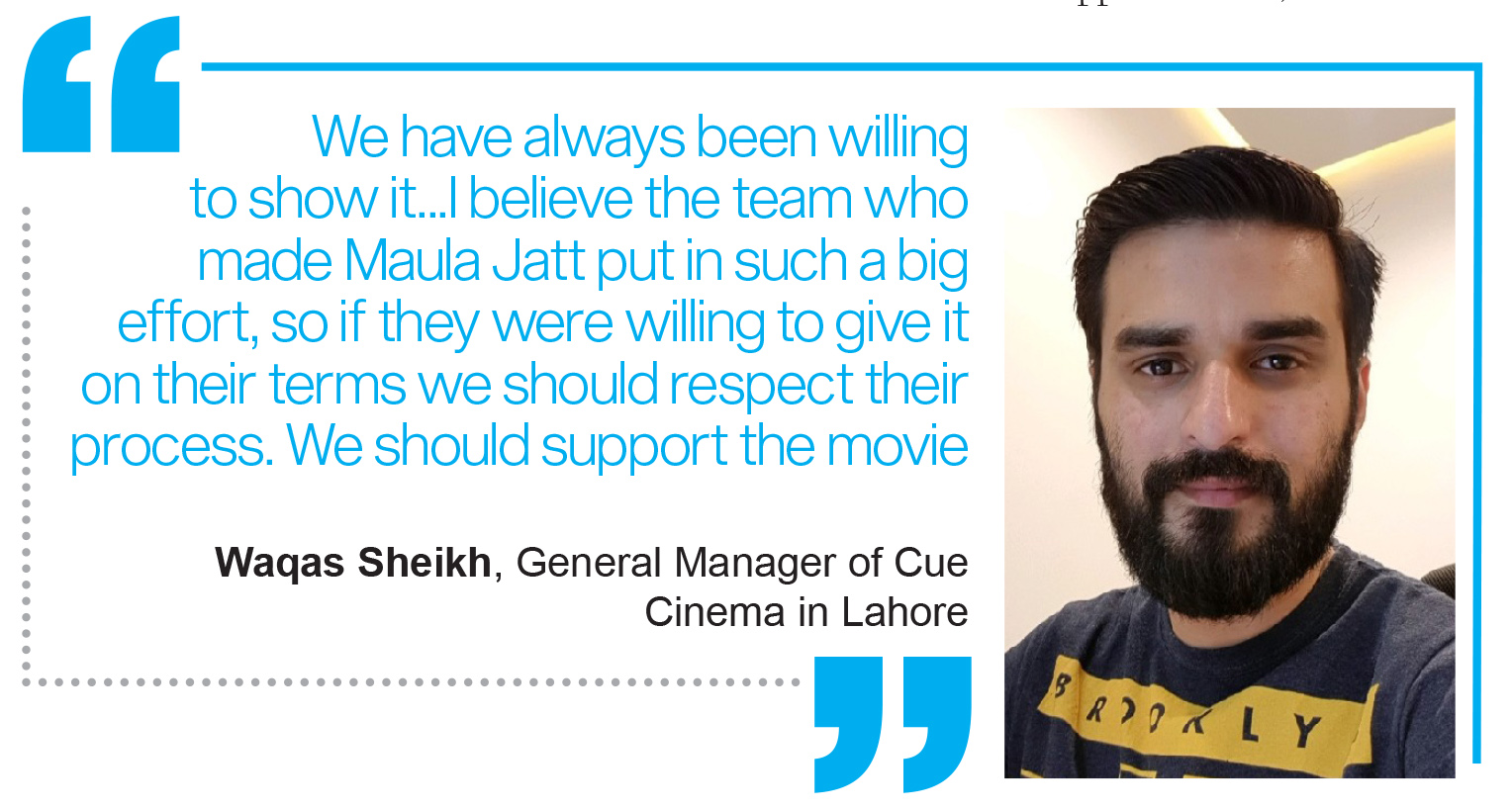

On the other hand, Waqas Sheikh, General Manager of Cue Cinema in Lahore said: “We have always been willing to show it.” Rubishing claims that they were selling tickets in black for Rs 5,000, he said, “I believe the team who made Maula Jatt put in such a big effort, so if they were willing to give it on their terms we should respect their process. We should support the movie.” With such a small cinema industry, Pakistan has no formal association but owners are closely connected and do discuss important issues that bind them. Despite this, they were unable to convince those who decided against agreeing to the terms of the distributors.

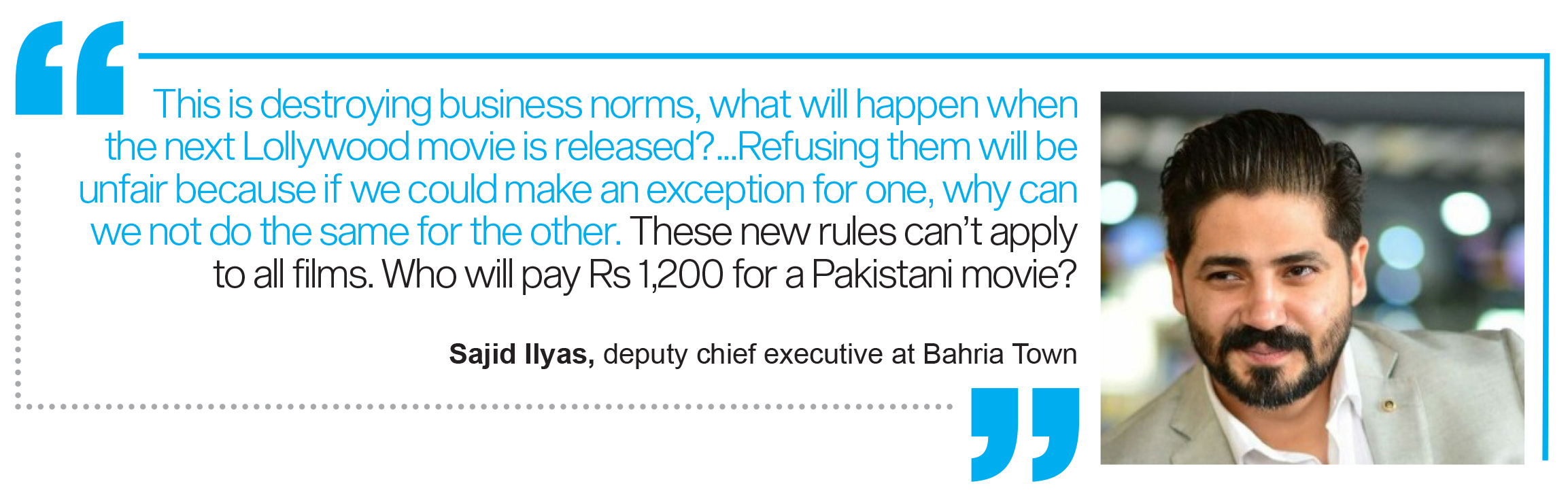

Sajid Ilyas, deputy chief executive at Bahria Town, which also has cinemas, says business dynamics have changed post-Covid, and that everyone should keep that in mind when trying to put new formulas in place. Moreover, while he understands that everyone wants to make the most of this big-budget and much-awaited film, it should not and cannot force anyone to compromise on the “fundamental principles” of doing business.

“This is destroying business norms, what will happen when the next Lollywood movie is released?” Ilyas said, adding that not every upcoming film has the size and scale of Maula Jatt but with a new precedent in place they will most likely also try to dictate terms. “Refusing them will be unfair because if we could make an exception for one, why can we not do the same for the other. These new rules can’t apply to all films. Who will pay Rs 1,200 for a Pakistani movie?”

Ilyas eventually agreed to the new formulas but called it a “compromise on business ethics” and said he was concerned about the future of the industry. He said he had nothing against Mandviwalla, and added that it is possible for both of them to be right in their own ways. Which is why he said they “swallowed a hard pill and conceded.” Maula Jatt was aired at cinemas in Bahria Town by day five.

How it ends…

Don’t worry, this isn’t a spoiler. Now that the 11-day period during which the distributors wanted the new formula applied is over, the movie is showing in the cinemas that rejected the demands. They are doing booming business. But it could have been more.

The verdict is still out on who will come out victorious. But there are some initial impressions.

“It will change the future for the better in two ways,” says Mahmood. “First of all, now international distributors and exhibitors have an example of a bankable Pakistani film so our upcoming films are more likely to open in newer markets.”

The Legend of Maula Jatt showed in over 300 screens abroad – a record by most accounts.

Mahmood continued: “Secondly, purely in terms of a Pakistani market, a precedent has been set that a good film is bound to draw crowds in regards of where and how it opens for exhibition. The local exhibitors will now think twice before acting like a cartel, and strong-arming Pakistani producers into deals that only favour the cinema owners. Pakistani producers now also have some cards in their deck.”

“Every movie makes money differently depending on variables that are unique for each project, said Hikmat. “That’s why movie production is not an ideal investment choice any investor would like to explore in a nascent market like Pakistan. That’s why even my own family insisted one should invest in real estate and not a film. Actually my husband, Asad Khan, who is also the executive producer, decided to finance this project in less than 15 mins after meeting Bilal. We made an unachievable financial projection with Bilal which solely relied on his creative vision. The market was not favourable. Covid made it worse.”

She also said she really wanted people to believe in this, to restore people’s confidence in Lollywood so that the industry could get investors. “In that sense, I feel like we have succeeded,” Hikmat said simply. And she is right, Maula Jatt has increased the box office size. Who will ultimately benefit more, the producers or the exhibitors? That remains to be seen.

In conclusion, to quote a line in the film: “One pride cannot be led by two lions.”

Or can it?

One cinema per 4 million people, must be a money spinner.

No, not when most of the millions don’t go to the cinema.

thanks for such an amazing and interesting article.

A very insightful article to highlight a much valid point, however I would have appreciated if some recommendations for the solution were also presented here.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com