Pakistan’s power sector is dying. Much like cholesterol clogging our veins, the circular debt in our power sector stands on the precipice of inducing a system-wide cardiac arrest. This is not a gradual, one paratha a day induced heart failure we’re talking about. Rather, Pakistan’s power sector is hurtling towards a cataclysmic collapse.One large coronary incident away from complete annihilation.

At the heart of the matter lies revenue collection. The Government of Pakistan has amassed a painful tab of Rs 2.7 trillion with every stakeholder in our power system, and the consumers it had earmarked to foot the bill are using less and less electricity with each subsequent price hike.

Our power system is a veritable maze of complexity, and its latest potential saviour is likely to baffle many. Pakistani companies, it seems, have reached their limit and thus have devised their own remedy to the chaos we find ourselves in. The solution? A reduction in electricity tariffs for industries.

Providing cheaper electricity at a time when electricity bills are soaring is, to put it mildly, perplexing. The government in response to this quagmire has been operating on a policy of sit and think. This is where lots of very important bureaucrats and politicians sit and vaguely discuss targets and measures whilst slurping tea and brushing biscuit crumbs off their chins.

But despite the much-ado-about-nothing behaviour, suggestions do filter in every now and then. And in recent days one particularly proposition has been gaining a lot of steam: Industrialist Electricity Tariffs. What does that mean? In very few words it means offering more affordable electricity to the wealthiest businesses in Pakistan. The proponents of this plan are, surprise surprise, big businesses. But what exactly does the proposal say and how in the world does it resolve our power crisis?

Capacity utilisation 101

Pakistan’s problem is it is far too hot. And the summer months are especially cruel in this heat.

Imagine, it’s midday, and the mercury has soared above a blistering 40°C. Without warning, the electricity supply is severed, leaving you marooned in the sweltering heat. The fan halts its comforting whirl, the lights surrender to darkness, and the refrigerator ceases it’s reassuring hum. Your provisions are on the brink of decay until the refrigerator revives, and your only solace is the hope that your electronic devices possess enough charge to tide you over until the power is restored.

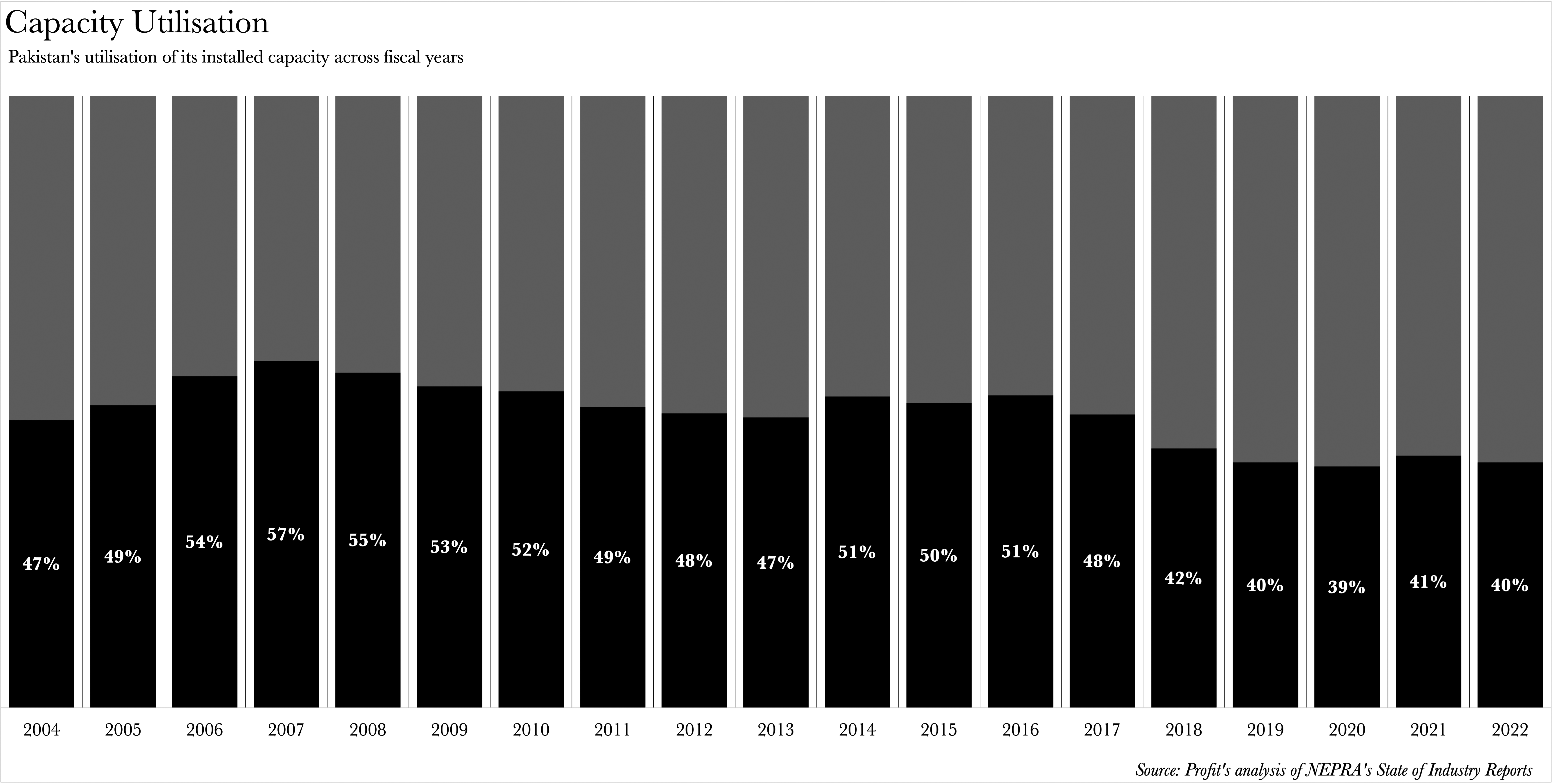

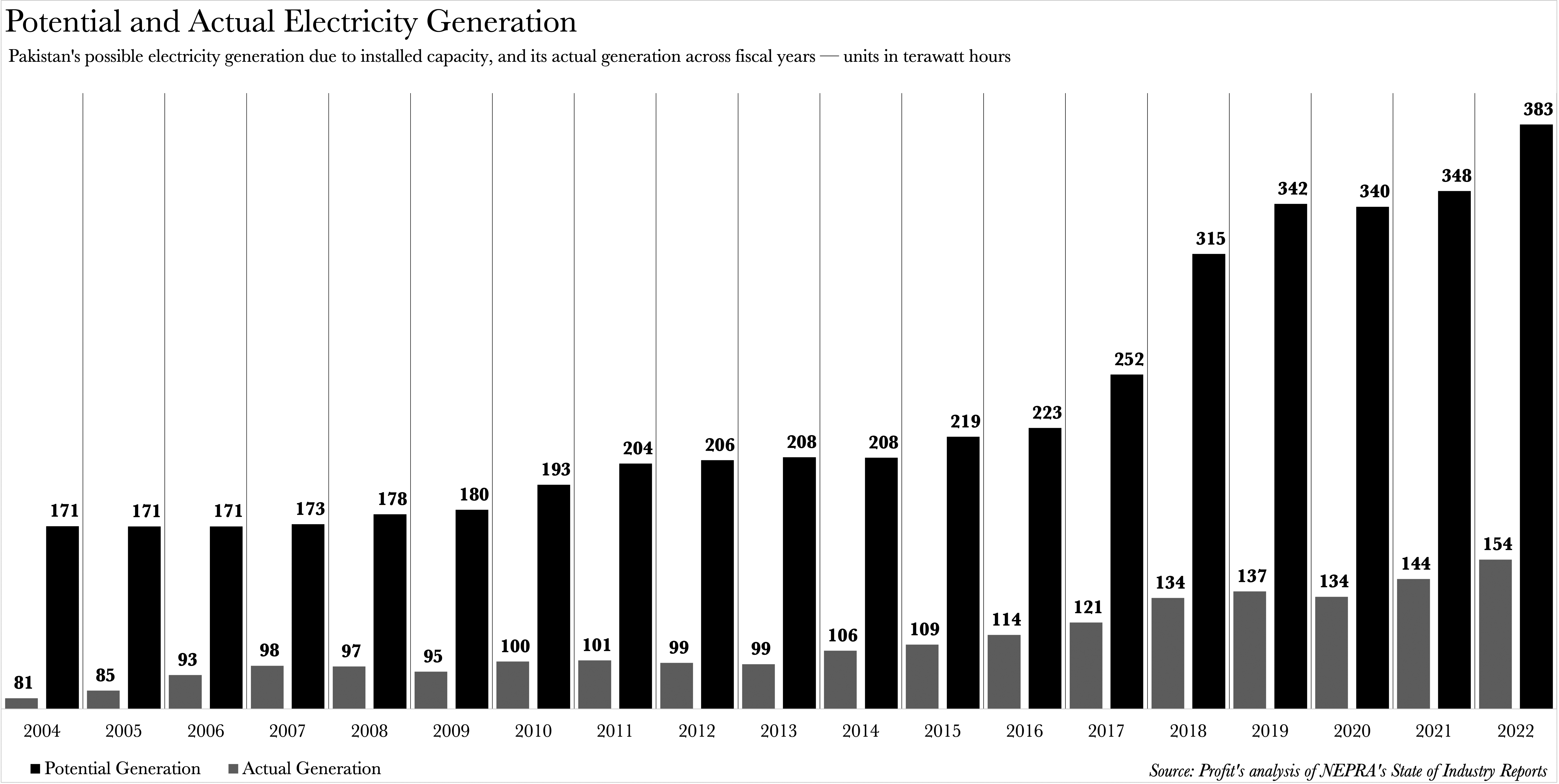

At this moment, the prevailing assumption is that Pakistan is simply deficient in its electricity supply. However, this is a misconception. In theory, Pakistan has an abundance of electricity — more than it can feasibly manage. The full potential of Pakistan’s power sector remains untapped. In other words, we have never truly harnessed the full output that our power plants are capable of generating. Our utilisation has oscillated between approximately 40% and 50% from the fiscal year 2004 to the fiscal year 2022.

Herein lies our quintessential conundrum. The invoices for the electricity that Pakistan generates remain largely unaffected by the rate of utilisation.

Herein lies our quintessential conundrum. The invoices for the electricity that Pakistan generates remain largely unaffected by the rate of utilisation.

At the heart of the issue is the Power Purchase Price (PPP). The PPP encompasses the cost of electricity generation, the capacity charge, transmission expenses, and market operator fees. It provides an approximation of the final electricity tariff, excluding taxes. The only additional costs are distribution and supplier margins, along with any adjustments from prior periods. However, it constitutes 90% of the final tariff, excluding these two costs.

The National Electric Power Regulatory Authority’s (NEPRA) benchmark PPP for the fiscal year 2024 stands at Rs 23 per unit. Out of this, Rs 16 are allocated towards capacity payments. But what exactly is a capacity payment?

A capacity payment is a fee paid by a user of an energy asset to the asset’s owner in exchange for the rights to utilise the asset’s capacity. Capacity payments are unique in the sense that they must be paid irrespective of whether a unit of electricity is consumed. Unlike the remaining Rs 7 in the PPP, which could potentially dwindle to Rs 0 if no electricity is consumed or generated, the capacity charge moves in the opposite direction. This is because it is based on an annual outlay of Rs 2 trillion, divided by the number of electricity units consumed by Pakistani customers.

“If everyone were to leave the country, and no unit of electricity were generated or consumed, then Pakistan would still owe Rs 2 trillion this fiscal year in capacity payments due to the sovereign guarantees it has granted,” says Dr Fiaz Ahmad Chaudhry, Director at the LUMS Energy Institute and a former Managing Director of the National Transmission & Despatch Company.

The converse is also true. The Rs 16 can be reduced at a per-unit level if more units are consumed. This is because the Rs 2 trillion outlay is for the installed capacity, while the Rs 16 charge is an estimate based on expected consumption. The aforementioned upward and downward revisions are possible based on the units consumed. This presents a paradox for the Government of Pakistan. It needs someone to foot the bill, otherwise, it will have to do so itself, as the capacity charge remains constant.

The more customers increase their electricity consumption, the lower the per-unit capacity payment, making it cheaper for everyone to consume electricity. However, the reverse is also true. The fewer people that consume electricity, the more expensive it becomes per person.

This is also what the Pakistani companies are pitching.

“You currently have surplus generation capacity that is not being utilised, so why not create incentives for the industry to do so? You are already paying the independent power producers for that capacity either way. Allowing industry to use the unutilised capacity at marginal cost would reduce the government’s burden, generate economic activity including jobs,” posits Ehsan Malik, the Chief Executive Officer of the Pakistan Business Council (PBC).

The current proposal for reduced tariffs, which the Government of Pakistan is contemplating, is also the brainchild of the PBC. So, how will this scheme function?

The PBC’s thought process

Just a bit about the PBC before we get into the details of this proposition. The PBC is a large umbrella organisation that advocates for macro policy changes that will be pro business in Pakistan. Since it has a lot of stakeholders, it is not exactly a lobbying organisation in the same way that industry associations are. This is a sort of loose confederation of big business in Pakistan that advocates for the freedom to do business and a good working environment in Pakistan. As such, one of the things you’d expect all industries across the board to agree to is that electricity should be cheaper.

Industries across Pakistan are currently subjected to a tariff that fluctuates between Rs 32 to Rs 38 per unit, exclusive of fuel charge adjustments. This rate is contingent upon their consumption patterns and the timing of their energy usage. The Pakistan Business Council (PBC) proposes a uniform rate of Rs 27 or 9 cents per unit for all industrial customers. They project that this would incur a cost of Rs 385 billion to the Government, under the assumption that the industry accounts for 25% of the total current electricity demand (140,000 Gwh x 25% x Rs11 = Rs 385 billion).

The PBC posits that this scheme would lead to an additional offtake of 1,500 megawatts, thereby reducing the net cost for the Government of Pakistan to Rs 180 billion (1,500 x 24 x 365 = 13,000 Gwh x Rs 16 = Rs.208 billion). They contend that the Rs 180 billion would be offset by the advantages of increased exports, reduced imports, job creation, and higher tax revenue resulting from the enhanced competitiveness of the industry.

The calculations seem plausible in theory. Consumer profiles across Pakistan’s power sector also support the PBC’s argument to some extent, particularly if the objective is to simply amplify the overall electricity consumption.

Industrial customers, despite constituting only 1% of the total connections, command a disproportionate 25% of the final demand for electricity. This stands in stark contrast to domestic customers who, while making up nearly 90% of the total customer base, account for just under half of the total consumption over the same period, from fiscal years 2016 to 2022.

Now then, what could possibly backfire in all this?

The considerations the scheme might need to incorporate

“The foremost question the industries should pose is whether they can procure a steadfast assurance from the government for a reliable electricity supply to satiate the escalating demand, particularly in light of our existing supply crunch,” argues Haneea Isaad, an Energy Finance Specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

What engenders this crunch and simultaneous underutilisation? Our energy mix.

Thermal energy reigns supreme as Pakistan’s primary energy source, constituting approximately 60% of the total, according to NEPRA’s State of Industry Report, 2022 — the most recent data available. Within Pakistan’s thermal mix, only Thar coal and domestic gas emerge as local solutions, with the fuel for all other plants necessitating importation. One of the reasons Pakistan does not fully utilise its installed capacity, aside from demand scarcity, is that when demand does surge, the fuels required to operate the plants cannot be imported due to our balance of payments predicament.

A similar dilemma manifests on a smaller scale during the winter months, when hydroelectric power nearly grinds to a halt due to weather conditions. The excess capacity is, in essence, nuanced. Our available capacity is restricted by whatever the grid can provide at any given time, and it is often curtailed by external factors. This, in turn, would inevitably lead to electricity rationing should demand skyrocket.

“You can supply electricity as close to the installed capacity as the foreign exchange position allows. When the marginal cost to provide electricity escalates, then you can prioritise it. You could, perhaps, allocate it to exporters, or to curtail supply to domestic users where the majority of the demand is for air conditioning in the winters,” explains Chaudhry.

Rationing would prove more challenging than one might anticipate. Firstly, prioritising exporters is not a novel concept. The All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) has long insisted that they be the exclusive beneficiaries of any tariff reductions, owing to the foreign exchange they generate for the country. The PBC, with their current initiative, are opposed to this bifurcation.

“Supply chains tend to be quite extensive. When providing energy at regionally competitive cost to the final exporter, what about those in the supply chain leading up to them? If they do not receive electricity at a competitive rate, then the cost to the final exporter escalates, which needs to be passed on to the overseas customers or absorbed by the exporter,” expounds Malik.

Rationing demand does not operate in such a straightforward manner. In a supply crunch, someone will have to be prioritised, lest no one is prioritised. The industrial versus domestic user debate is even more contentious.

Curtailing domestic demand is unlikely to resonate well with the Government, given their need for votes. It has protected categories; we can’t touch them. It has unprotected categories, which are already bearing a steep price. The upper tier of domestic customers are already paying even higher than the industrial segment. It’s an incredibly delicate matter altogether.

Industries will have to ensure that the Government can devise a strategy to provide them with a reliable supply come what may, otherwise they risk production interruptions themselves.

Then there is the cost of the entire initiative. The companies will likely achieve the boost in economic activity they are pledging in the long run. But what about the immediate consequences?

“In light of Pakistan’s tenuous macroeconomic climate, the luxury of an additional subsidy is one we can ill afford,” Isaad explains. “The power sector operates on a model of cross-subsidisation. Our energy mix leans heavily on imports, leaving us vulnerable to external shocks that could send the cost of generation — and consequently, the net cost of reduced tariffs — into a tailspin,” Isaad adds.

The PBC, however, staunchly refutes the notion that they are beneficiaries of a subsidy.

“The term ‘subsidy’ is a misnomer in this context,” Malik asserts with conviction. “If you compete globally, customers will not pay for inefficiency of inputs. A subsidy would be a reduction beyond justifiable cost of generation and delivery of power. The removal of an unjustifiable burden such as charges for unutilised capacity, transmission and distribution losses, theft, under-recovery etc is not a subsidy. It is a price correction,” Malik asserts.

The PBC further contends that they are, in fact, subsidising the rest of Pakistan’s power consumers. “The industry presently covers the cost to generate electricity, compensates for the transmission and the associated losses. It also shoulders the burden of theft committed by others and the non-recoveries by the distribution companies,” Malik affirms.

Could there be a middle ground in terms of the initiative’s cost? Chaudhry believes so. He proposes a simple solution for exporters: the Government could recoup the additional costs by offsetting them against any tax benefits the companies receive on exports. For companies serving the domestic market, Chaudhry suggests a straightforward approach of stock keeping and inventory management. The additional output resulting from the lower tariffs could easily be charged to the companies at a fair rate.

“The goal,” Chaudhry indicates, “to ensure that the cost of electricity remains reasonable for all, especially the industrial consumers. Should the cost of generation escalate, the Government should look for opportunities to adjust it in the profits that the power companies earn and in the fuel prices that their respective plants use.”

Is this the end of the story? There is one final argument that advocates for slashing tariffs across the board, should the ultimate ambition be to amplify utilisation rates. This is what Hammad Azhar, the former Minister for Energy, did in October 2021 for the winter season. To his commendation, electricity consumption skyrocketed. Thus, one might ponder — why not replicate this strategy?

This query takes on paramount importance if another pivotal goal is to diminish the capacity payment for all, thereby enabling a greater use of electricity. Whilst industrial consumers guzzle more electricity than their domestic, commercial, and agricultural counterparts, they are eclipsed by bulk and miscellaneous users on a per connection basis. If electricity were to be perceived merely as infrastructure, then the objective would undeniably be to maximise the number of individuals harnessing this infrastructure. Correct?

“The aspiration should be to employ electricity in a productive manner. Allocating our energy use for consumptive purposes is the very pitfall that ensnared our power sector in its current quandary,” Chaudhry posits. His argument, though cogent, is likely to present the primary hurdle for the project, should it ever receive the green light.

It may indeed hold true that other customers do not generate economic activity at a level commensurate with the industrial sector. However, this does not imply their contentment with such an arrangement. Consequently, industrialists may find themselves needing to secure a plethora of assurances that this will not be a commitment the Government of Pakistan backpedals on.

Sovereign assurances from an unreliable sovereign

As we draw to a close, let us revisit the aforementioned sovereign guarantees for the capacity payments. The Government of Pakistan is legally bound to honour them. However, whether it fulfils this obligation in a timely manner is a different matter altogether — and that is how we ended up in our circular debt.

The notion that the Government of Pakistan will bestow some of the wealthiest enterprises in the country with access to more affordable electricity whilst the tariffs skyrocket for everyone else is unlikely to garner any public support. This holds true despite the potential long-term benefits that such an endeavour may bring forth for the common good.

The amalgamation of the Government of Pakistan’s historical unreliability and the political pressure that will intensify if electricity rationing ensues will put industrialists in a quandary they would rather eschew. Our power infrastructure is in a state of chaos, and any effort to amend it is indeed commendable. The month of December 2023 witnessed a generation output that fell short of the figures from December 2017. There is no room for prevarication — our system is shattered and totters on the verge of further decay. If there ever was a time for inventive cogitation, it is this very instant.

However, for this venture to yield fruit, the industrialists will need to meticulously compute all feasible calculations. The crux of the argument at present is that higher consumption, if viewed as the denominator to the total outlay for capacity being the numerator, then the per unit cost will diminish for all. The gamble on this particular cohort of users is that they possess the requisite multiplier to not only invigorate the local economy but also usher in the necessary foreign exchange to maintain the steady supply of fuel needed to generate the additional demand for electricity that they will engender.

All of this pivots on the proposition that they can achieve something concrete before the Government of Pakistan harbours any second thoughts. Consequently, the guarantees are almost as crucial as the mathematics upon which the initiative is predicated. A considerable number of industrialists are proprietors of their own independent power production companies. Perhaps these industrialists, in particular, can illuminate their peers about the discrepancy between the promises proffered by the government and the actual treatment that is dispensed once the ink solidifies on a monumental accord.

Good guidelines for the industry indeed.