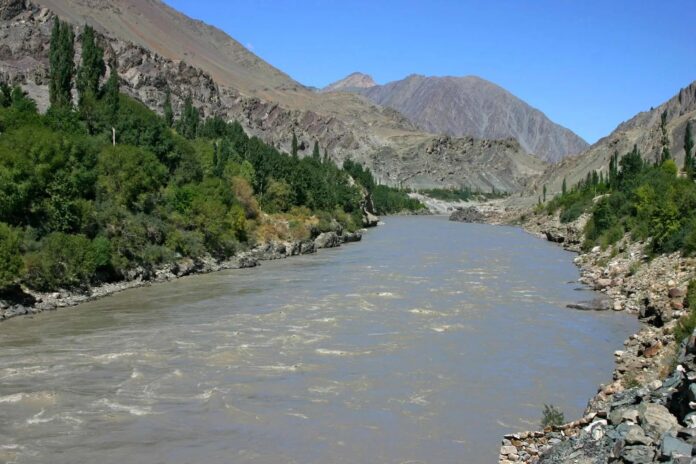

In the final months of 2025, Pakistan’s agricultural sector was shaken by a crisis that not only devastated crops but also brought attention to the growing tensions over water control in the region. The Chenab River, a vital artery for Punjab’s agriculture, swelled to catastrophic levels, flooding thousands of acres of farmland that were supposed to be nourished by the river’s steady flow. What caused this sudden surge? India’s decision to release large volumes of water from its upstream reservoirs, triggered by severe flooding within India’s own borders. This was a necessary move for India, forced by its own monsoon rains and flood management needs. But for Pakistan, the release highlighted a much more serious issue—the increasing unpredictability of water flow from shared rivers, especially the Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus, all of which flow from India into Pakistan.

India’s sudden water release was not the problem per se. The issue lies in India’s failure to notify Pakistan, as stipulated under the Indus Water Treaty (IWT). Under the IWT, India is required to inform Pakistan before releasing significant amounts of water, a crucial provision designed to prevent agricultural disasters like the one that just occurred.

Over the past week, we have once again seen the issue of water take centre stage between India and Pakistan. Irregular changes in the flow of the Chenab and Jhelum have left the wheat crop in some regions severely strained. On December 14th, the inflows and outflows of the Jhelum River at Mangla stood at 5,000 and 33,000 cusecs, respectively. However, inflows decreased to 3,300 cusecs on December 15 and remained at that level until December 19, while outflows remained at 33,000 cusecs. Water flow at the same time last year was recorded at inflows of 4,400 cusecs and outflows of 25,000 cusecs.The office of the Pakistan Commissioner on Indus Waters said that the Jhelum River was experiencing reduced inflow from upstream in India to downstream at Mangla Dam. The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan