It all started with a visit, as all good bureaucratic wormholes do. On the outskirts of Faisalabad, within what is part of the Faisalabad Municipal Corporation (FMC), but doesn’t quite feel like it, a team from the commissioner’s office arrived in the lazy days before Eid.

Hanif watches as the team from the commissioner’s office hoops and hurdles its way over open sewage lines and unpaved roads, holding their forearms to their noses in meek attempts to block out the overpowering stench of animal waste.

Eid is a busy time for municipality employees. With animal markets setting stage and small scale vendors roaming all over the city trying to make a buck, there’s all kinds of smells and mess making the city a nightmare. And that’s where the municipality workers come in, strutting around demanding permits and often also just out there trying to make a buck.

Which is what makes this visit so strange. Living in one of the most dilapidated areas of Faisalabad, Hanif is also an animal farmer by profession. And while this means he is regularly hounded by the municipality, his product is milk, not meat. So at least for the time that the cattle markets are still alive, he expects the FMC to be too busy dealing with the Eid influx to care about the handful of cows he has tied up in the confines of his shabby home.

As the inspectors arrive, you can smell trouble in the air better than you can smell the animals. Usually when the inspectors come knocking, they expect bribes. A few thousand here, a few thousand there, there’s usually a strict per cow number that both parties are aware off. The municipality people huff and puff and the farmers grumble and complain but the transaction is completed and life goes on as it always does.

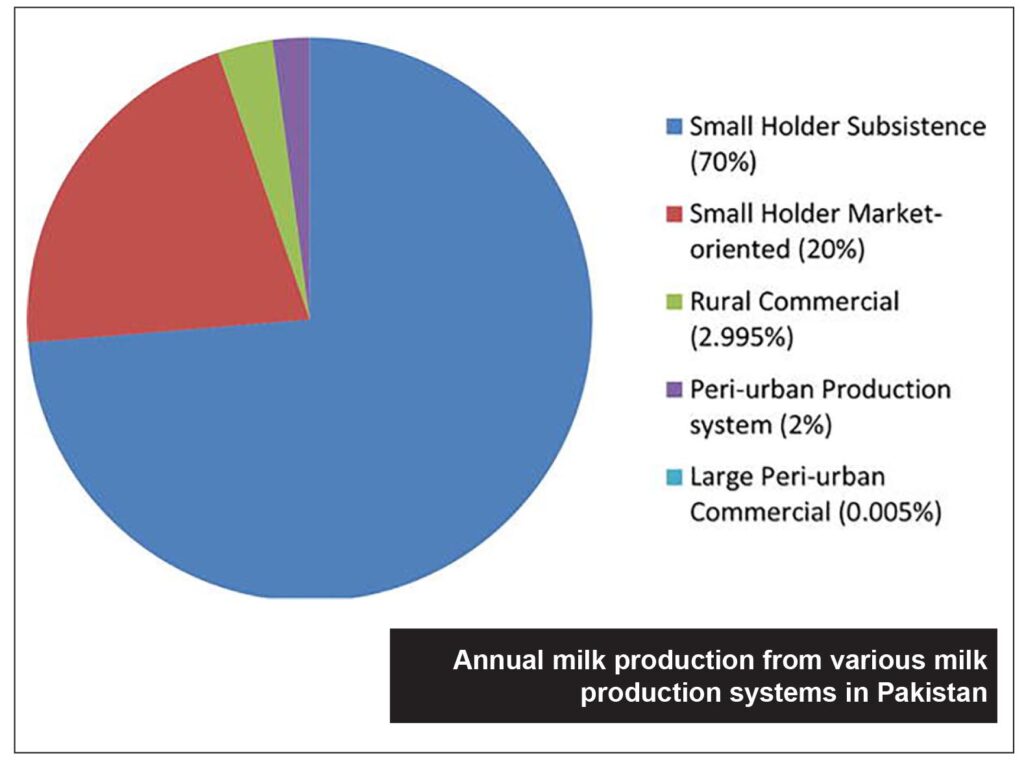

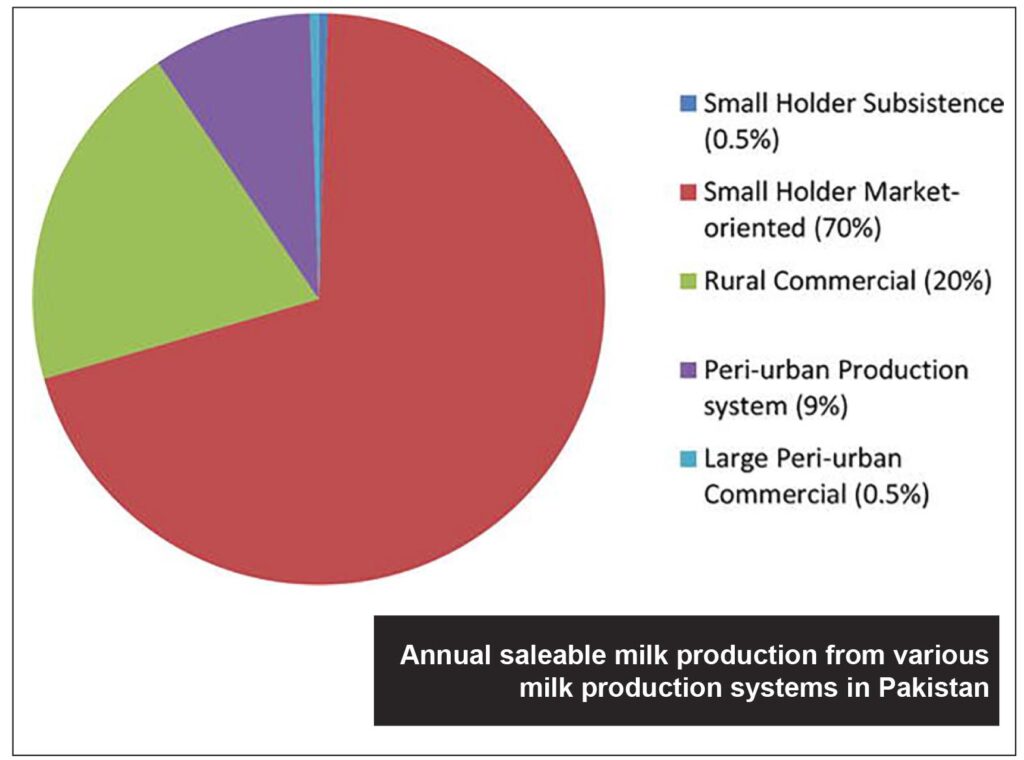

But the game is different today, and the people making their way through the neighbourhood aren’t here for petty bribes of fines. On the peripheries of Faisalabad where this show down is taking place, there live around 500 dairy farming families. Each family has between 5-10 buffaloes to their name, and all of them live off the meagre fare selling this milk gets them. It is, essentially, a milk cottage industry. A cottage industry that, by the way, produces 20% of Pakistan’s annual milk production, and 70% of the country’s saleable milk production as per Pakistan’s 2016 livestock census.

And the commissioner’s people are there to shut the whole operation down. You are within the limits of the municipality, and you can’t keep cattle on your residences they say. The team was there to evict the cattle, but in effect they were evicting the people as well. Because without their animals, they have no livelihood.

What followed was a fascinating few days that displayed how politics, bureaucracy, local government, and classist hysteria come together to try and oust from Faisalabad a community vital to local economies all across the country.

There were delays as Eid did in fact give the dairy cottage farmers some respite. And then a push to have them out again. The farmers followed up this latest deadline by going to the Lahore High Court (LHC), and the court gave them a stay.

For now, the eviction stands still, awaiting a response from the commissioner to explain his decision to have the farmers moved out. But how long will the farmers will be able to hold their ground assisted by the law? What if any effect will there be on Faisalabad’s milk market? And how in the world are we supposed to accommodate dairy cottage farms within cities, without risking health hazards?

Pardon the pun, but where’s the beef?

Milk men are evil. In Pakistan they don’t come strolling to your doorbell with a six pack of milk bottles, bow tie slightly crooked, and humming a tune. In Pakistan, they arrive on a broken down Sohrab motorcycle, struggling to carry the weight of the huge copper drums slung carelessly on either side. The fumes from their ancient two-stroke bike producing and evil black hue that undoubtedly affects the milk in some way or the other.

They also aspire to make sure your kids don’t grow tall. Which is why they all conive to mix water in your milk and inject their animals with the worst kind of steroids that will speed up your journey to the afterlife. That, at least, is the perception countless television exposes have fed to us.

Perhaps no one symbolised this milk hysteria more than former Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Justice Mian Saqib Nisar. While his lordship had taken to heart many issues and liberally used his suo motu powers, his fear of the country’s dairy situation was enough to grab international attention. When the economist profiled his honour, they captioned a full length picture of him beautifully – “judge, benefactor, milkman.”

But looking at Hanif and hearing him talk, he doesn’t seem like the monster that every gawala has been made out to be. He’s just trying to get by. And for all we know, he is among the many gawalas that mix milk in their water and charge high prices and juice up their buffaloes.

This might make you think, why care about 500 small scale dairy farmers. Maybe it’s sad that they’re being evicted, but what’s the big deal if they have to move a few blocks over? What you’re not realising then is that people like Hanif are actually significant contributors to the economy. And the problems they face are not peculiar to Faisalabad.

Pakistan is among the leading raw milk producing countries in the world. Unlike production systems in developed countries such as the US, however, milk production systems in Pakistan are typical of developing South Asian countries. This production system characteristically is a mix of traditional and commercial methods, although the traditional beats out the commercial in volume due to the sheer number of small scale dairy farmers.

According to the Livestock census of 2016, a whopping 70% of the milk producers in Pakistan are subsistence based, compared to a miniscule 0.5% of large peri-urban commercial milk producers.

The 500 small scale dairy farmers that Hanif lives with at the edges of Faisalabad milk their animals and end up selling at least 70% of the produce, using the rest for themselves. They sell to local shops and on fixed routes. Going by the census, these 500 would be categorised as market oriented small scale holders.

This is because while living on the edges of Faisalabad and selling to the city’s population makes them peri-urban, since they have smaller herds ranging from 5-15 animals at most, they also have certain characteristics of rural commercial farmers. This is even truer since a number of these 500 settled families came from nearby rural areas such as Jhang, where they had been practicing rural commercial dairy farming, due to repeated floods.

Small scale holders that are market-oriented thus end up producing a vast 70% of saleable milk from the various milk production systems operating in Pakistan.

With 10 animals per household producing up to 8 liters a day, the 500 dairy farming households facing eviction in Faisalabad can produce up to 40,000 liters of milk on a good day. According to a study in the Pakistan Journal of Agriculture, 50% of the milk produced in Faisalabad district is consumed by the city itself. Of this 50%, the larger scale commercial farmers sell to other cities and bottle their milk. The 500 dairy farmers facing eviction have a key role to play in this 50% consumption within Faisalabad.

What they’re up against

When the commissioner had made his desire known to have Faisalabad cleaned up in one fell swoop, Hanif and his fellow farmers were indignant, not bewildered. They knew they were within the FMC jurisdiction, but while they claim they had no knowledge of the legality of keeping cattle within the municipality, what they do know is that they are part of the municipality in name only.

The commissioner of Faisalabad, Mohammad Javaid Bhatti, has seen himself become the man in charge of Faisalabad in wake of the recent dissolution of local governments by the PTI. When contacted, he was unavailable to speak at length, having gone to Islamabad for training. But his office did inform us that the decision to evict the farmers was taken after multiple health and cleanliness concerns were raised.

True enough, the conditions in which this milk is produced are filthy. Animal waste and animals not only make it an ugly sight to behold, but also a haven for disease. “The commissioner took the initiative on his own after a number of complaints. He gave time to the people and gave multiple warnings before taking action” his office explained.

What they couldn’t explain, however, was the lack of municipal facilities in the area. While the commissioner says it is part of his jurisdiction, there is no sewage or waste disposal mechanism in place in this area – where experts say there should be extra care because of the animals.

An eyesore it may be, but as far as the farmers are concerned, that is the municipality’s mistake, not theirs.

The question is one of sustainable living. This cottage industry for dairy provides Faisalabad with a significant portion of its milk. But the facilities they recieve are next to nothing, which ends up promoting unhygienic and putrid conditions for milk farming. And this is not peculiar to Faisalabad. While the eviction may be their headache for now, all over the country, peri-urban and small scale market-oriented farmers face similar conditions in which to farm their product – and often similar hurdles.

They have bigger problems to deal with than possible evictions. For example, as the earlier mentioned paper in the Pakistan Journal of Agriculture points out: In Pakistan, peri-urban dairy farmers are usually poorly connected to financial institutions and livestock services, and get negligible returns from their dairy enterprise. Other existential problems include high calf mortalities, unsystematic breeding, imbalanced feeding, high loans and a hostile marketing system dominated by middlemen.

Of course, moves such as this eviction attempt are nothing new for Hanif and his fellows. Ambitious, but unelected functionaries often victimize marginalised and lower income communities in their clean up drives. Ask the farmers, and they will tell you how such moves are made every few years. While they say these attempts are usually stalled by bribes, this time around the municipality is serious.

“This operation against the small dairy producers is part of broader anti-poor bias of our bureaucratic elites” argues Usama Khawar, the lawyer that has taken the FMC to court on behalf of Hanif and the other dairy farmers.

“We have seen dispossession of poor in the form anti-encroachment drives in Islamabad first against katchi abadis and more recently against kiosks; in Karachi against small shop-keepers and informal settlements; and now in Faisalabad” he says.

“What is significant; all of these anti-poor operations were conceived and led by unelected officials and same is the case in Faisalabad in present instance. The Administrator of Faisalabad is an unelected bureaucrat.” he added.

But in addition to these biases and structural difficulties they face, there also seems to be a political challenge. The farmers have alleged that there is more than just cleanliness behind their eviction. They allege that the operation is taking place at the behest of Khurram Shehzad, the incumbent MNA for NA 107 (Faisalabad VII). Khurram’s interest in having the farmers evicted is that they would no longer be in his constituency, and be the one polling station in NA 107 that defected for the League.

While Khurram Shehzad has not responded to Profit’s attempts to contact him, one can never put too much stock into such claims. The numbers of the farmers are paltry enough that Shehzad wouldn’t go out of his way to get them chucked out. But at the same time, the farmers are insistent, and have made it part of the case they are pursuing against the FMC in the LHC.

The court case

The legal system, for now, has at least backed the farmers. The LHC has restrained the Faisalabad Municipal Corporation from displacing the dairy farmers and directed the commissioner to decide their application within two weeks strictly in accordance with law.

Usama Khawar argued on behalf of the petitioners that the authorities were determined to uproot the dairy producers, destroy the livelihood of thousands of citizens and push them into poverty by displacing them through illegal, mala fides, and politically motivated coercive action.

Ironically enough, counsel told the court that the municipal corporation invoked Punjab Local Government Act, 2013 against the petitioners which was a repealed law. The repeal of the PLGA 2013 in the wake of the PLGA 2019 is what had elevated the commissioner to the position of de facto mayor, yet it was the PLGA 2013 he used to have the farmers evicted.

Profit’s detailed dive into the PLGA 2019 compared to the PLGA 2013 in a previous issue had discussed in passing that issues such as dairy farming should be dealt with by the local government, and in the absence of these elected representatives, unelected state functionaries such as the commissioner are given free reign to do as they will.

Such functionaries cannot very well understand the importance of such communities to local markets and economies. They often brush aside the fact that many of these people have been doing this work for decades, inheriting their small properties from their fathers. And in their zeal to clean up, they often bulldoze instead of fixing important structures such as this particular cottage industry.

For now the court has simply given a stay, a win for the farmers, but an unstable one and easily set aside. What they will have to argue in front of the judge is not just their right to their livelihood, but also their right to facilities that the municipality should be providing them.

As important contributors and providers of the local economy, they should ideally receive not just municipal facilities but additional support to ensure that they can work and produce hygienically and in peace.

The point to be made here is a legal one, relating to arbitrary removal and right to property, and on some level even a constitutional one, relating to the overreach of unelected functionaries such as the commissioner of Faisalabad.

But it also presents the opportunity to set a precedent that could boost the peri-urban farming industry and increase the standard of milk being produced. Simple sewage facilities and stricter regulation could mean these small scale farmers could have proper sheds within their homes to sequester their animals in.

A cleaner area with paved roads could also encourage the setting up of milk shops by these farmers, and cut out the middle men that often leave the farmers themselves with little to take home from their produce.

This might even help tone down some of the more hysterical anti milk-mafia elements in media and whatsapp circles.

Very nicely written but the future is not bright for these people. Their small operations are inefficient. Large scale dairy farming will put them out of business even if the government lets them carry on for now.

Comments are closed.