Perhaps we should have seen this coming, but count us surprised. Share buybacks – the practice of publicly listed companies buying back their own shares from the stock market – have come to Pakistan. Long a mainstay of the capital markets in the United States, they now appear to have a place in Pakistan’s nascent markets as well.

Over the past few months, at least two major Pakistani companies – backed by two major Pakistani financial and industrial conglomerates – have announced share buybacks. On July 25, 2019, JS Investments, the asset management company that is part of the broader JS Group, announced that it would be buying back Rs503 million worth of shares, equal to 34.8% of the company’s total outstanding shares.

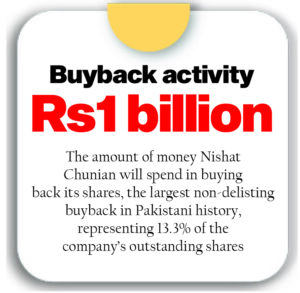

Then, just two weeks later, on August 9, 2019, Nishat Chunian Ltd, the textile company that is part of the broader Nishat Group, announced that it would be buying back Rs1 billion worth of its own shares, equal to 13.3% of its total outstanding shares.

These two transactions are not the first of share buybacks in Pakistani history. Indeed, they are not even the first share buybacks for the conglomerates in question: JS Global Capital, the investment banking and securities brokerage subsidiary of the JS Group, conducted a similar share buyback in 2016. During that year, JS Global Capital spent Rs552 million buying back 12 million shares, which at the time represented 24% of the total number of shares outstanding, and nearly half of the company’s free float.

And while three data points are not necessarily a trend, given how novel this phenomenon is in Pakistan – and how prevalent it is in mature capital markets like the United States – it is worth exploring what share buybacks mean for investors, and the broader Pakistani economy.

The financial economics of buybacks

Let us start with a recap of some corporate finance basics, which will help explain why corporate buybacks are possible, and why companies even contemplate them.

When a company makes profits, there are essentially five possible choices it has as to what it can do with the money it has earned, and it can choose any combination of these five:

- Spend it on capital expenditures

- Spend it on buying other companies

- Keep it for a rainy day

- Pay it out as dividends

- Buy back its own shares

Each of those has a different outcome, both from the perspective of management and investors in the company, as well as the economy.

And the two perspectives are not always aligned. In theory, the job of a CEO is to allocate capital efficiently and continue to grow their business, and by extension create jobs and grow the economy. Doing that job well can result in CEOs being very highly compensated. In practice, however, it is possible for the CEO to earn a high income by rewarding shareholders without necessarily contributing to the growth of the broader economic pie. And the most popular way of doing that – at least among CEOs of American companies – is share buybacks.

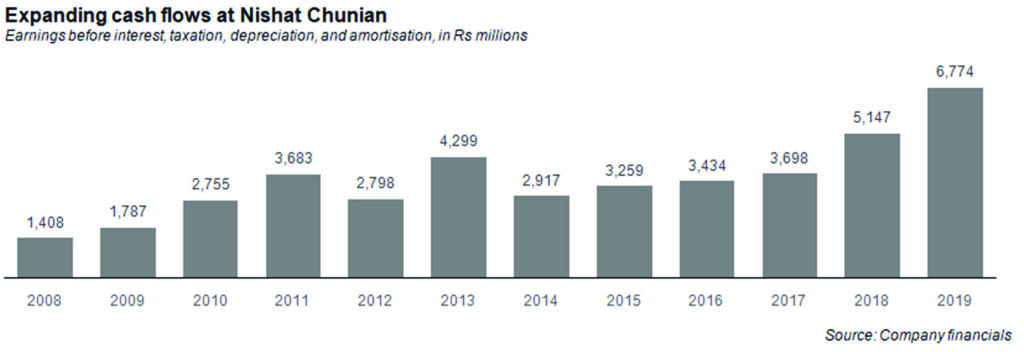

Owing to reasons relating to both finance theory as well as taxation laws, instead of net income, it is easier to examine what a company does with its free cash flow. A quick proxy for free cash flow, and one used for the purposes of this analysis, is earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA).

From a company’s perspective, the first two options – spending on capital expenditures or mergers and acquisitions – are both ones that involve the most risk and the most reward, with capital expenditures often involving more perceived risk than even mergers and acquisitions. And that makes sense intuitively: it feels a lot riskier to set up a completely new factory from scratch rather than buying a running factory from another company, where at least the revenue and profits are known variables.

From an economy’s perspective, though, the riskiest option – capital expenditures – if successful, is clearly the best option: a new factory or business unit would require the company to hire new staff (creating new jobs), create relationships with suppliers (creating new sales for other businesses), and ultimately pay taxes (new revenue for the government). Mergers and acquisitions may result in higher profits, and therefore higher tax revenue for the government, but not necessarily new supplier relationships, and often result in job losses as redundant employees are let go.

Among the largest global companies, Amazon is famous for always choosing option one: the company will invest as much of its free cash flow as possible in new projects, resulting in Amazon becoming one of the most valuable companies in the world.

The third option – saving the money for a rainy day – is somewhat neutral. From both the economy and the company’s perspective, doing so achieves one major goal: risk mitigation. Saving cash during a boom means a company will have more cash when there is a recession, which in turn will likely mean that it can keep its business open despite hardship. From the broader economy’s perspective, that may also mean being able to avoid layoffs during an economic downturn, and perhaps even keeping salaries steady.

Some companies – such as JPMorgan, the largest financial institution in the world – use option three as a countercyclical growth strategy: save money while everyone else is investing, and then, when the rest of the market runs out of money during a recession, go out and buy all the good assets that are now cheap because nobody has the money to buy them. Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan, refers to this strategy as the “fortress balance sheet”.

Others, such as Apple, simply hoard the cash and opportunistically deploy it in acquisitions as and when needed, but otherwise sit on a mountain of money. As of June 30, 2019, Apple was sitting on $94.6 billion in cash and cash equivalents (short term investments that can quickly be converted into cash, such as term deposits, money market funds, etc.).

What the first three options have in common is that they are some form of investment: each of the three options involves some element of strategy whose ultimate purpose is to grow the company’s revenue or profits, and usually both.

That is not true of the last two options, which are both just two different ways of returning capital to shareholders.

Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with returning capital to shareholders. After all, that is the stated purpose of existence of all for-profit businesses. Indeed, the value of a company is calculated by estimating how much cash it can generate for its shareholders.

But returning capital to shareholders means that management has decided not to use that cash to grow the company. That does not mean that returned capital – whether in the form of dividends or share buybacks – cannot still help grow the economy. After all, shareholders who receive the dividends or buybacks can reinvest that capital in other, more productive companies.

Of these two options, dividends are the one that result in all shareholders receiving the cash back from the company, and are generally taxable at a higher rate than capital gains, which means that the government tends to receive more in revenue from dividends. By comparison, share buybacks result in cash capital gains only for the few investors who sell their shares as part of the buyback, though the unrealised capital gains are available to all investors. The cash capital gains are generally taxable at lower rates than dividends, resulting in lower revenue for the government.

The Pakistani context of buybacks

While each of these choices have different consequences for both companies and the economy, these are not exclusionary choices: most companies can and do select multiple options each year, and can switch between them over the course of several years. Paying dividends does not preclude the possibility of capital expenditures, and vice versa.

Hence, to understand the consequences of a company’s choices, it is helpful to examine the relative weight of each option in the company’s decisions on how to deploy its capital. The biggest criticism of share buybacks is not that they are an inefficient use of capital. It is that if they become the dominant use of capital, they could perhaps represent an abdication of responsibility on the part of management.

In other words, a company’s CEO may decide to do share buybacks because they have simply run out of ideas for what to do.

“If a company is buying back equity, then one reason could be that it has run out of new ideas, or they don’t have enough new ideas,” acknowledged Shahzad Saleem, CEO of Nishat Chunian Ltd, in an interview with Profit.

For the purposes of this analysis Profit focuses on Nishat Group. While both JS Group and Nishat Group initiated share buybacks, the JS Group companies are both financial institutions which have different dynamics that are not directly comparable to non-financial companies. Balance sheets and income statements are organised differently for financial institutions and capital expenditures, though not wholly absent, are a less relevant feature of a financial services company’s business strategy.

By contrast, an industrial company offers the kind of characteristics that most other companies – including some services companies – might face, and thus has more applicable lessons to offer.

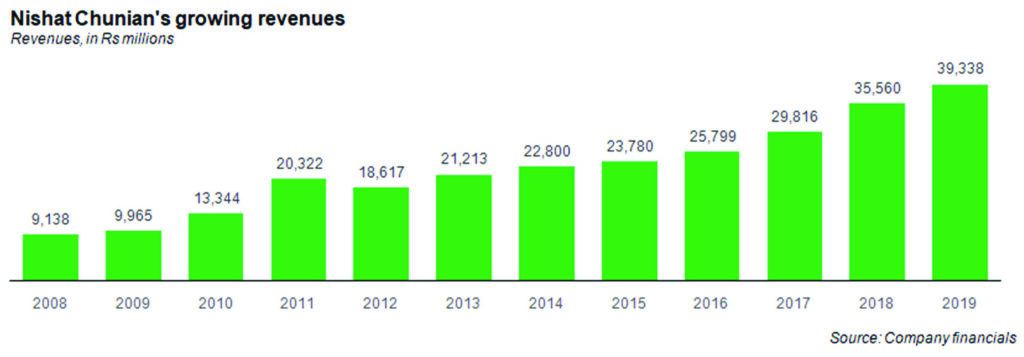

Our analysis of Nishat Chunian indicates that it is far from being the kind of company that is out of ideas on growth strategy. Then why did it go for a buyback?

A bit about Nishat Chunian

Nishat Chunian Ltd was established in 1990 as part of the Lahore expansion of the then-Faisalabad-based Nishat Group, which owned Nishat Mills Ltd, what is now – and has been for decades – the largest textile mill in Pakistan.

At first, Nishat Chunian was the most basic form of industry: a spinning mill that spun ginned cotton into cotton yarn. In 1998, however, the company invested nearly Rs700 million to diversify its product offerings into weaving: manufacturing cotton cloth out of the yarn it was producing. Over the next few years, it continued to expand its spinning and weaving capacity until, in 2006, the company finally entered the home textiles business (bed sheets, linens, etc.)

By 2010, the company had set up its own independent power generation unit that not only supplied its power plant with electricity, but in fact sold electricity to the national grid. That subsidiary was eventually listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange as Nishat Chunian Power Ltd. In 2014, the company invested in expanding the power generation capacity of NCPL by adding a 46-megawatt (MW) coal-fired power plant.

In 2015, Nishat Chunian tried diversifying by investing in a cinema operating business, though that business was eventually sold off as management decided it was too far removed from the company’s core business. They did, however, decide in 2016 to invest in creating their own retail outlets called The Linen Company (TLC), which was a vertical integration for the domestic market.

Needless to say, that short history illustrates the fact that this is a management that has been more than willing to take risks and think creatively. This is particularly impressive, considering the fact CEO Shahzad Saleem has been at the helm of the company since 1997, and has been involved with the company for even longer. Typically, CEOs with long tenures tend to get complacent and stop innovating, though that is evidently not the case with Nishat Chunian.

Shahzad Saleem is the son of founding CEO Sheikh Mohammad Saleem, and the nephew of Nishat Group chairman Mian Muhammad Mansha. A graduate of the University of Karachi, Shahzad then went on to do his MBA at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in 1989, one of the earliest batches to attend what is now inarguably Pakistan’s finest institution of higher learning.

“The interview for admission into LUMS was held at Packages Ltd. office in Karachi by Syed Babar Ali, Abdul Razak Dawood, Javed Hamid, Yusuf Shirazi, Ehsanul Haq and Waseem Azhar,” he said, during a 2012 interview with his alma mater, highlighting just how seriously the university’s industrialist founders took their commitment to the institution in its early years.

Following his graduation from LUMS, Shahzad Saleem joined the Nishat Group, and has been working with Nishat Chunian Ltd since its inception.

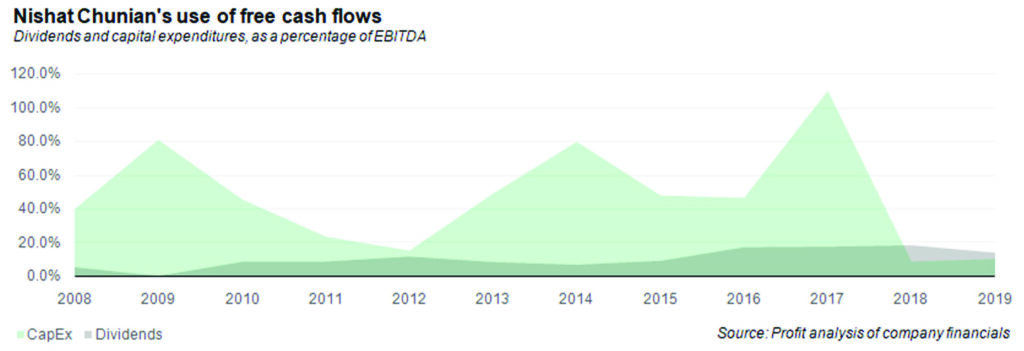

One would assume that such a company would be ripe for complacency and stagnation, but over the past decade – Shahzad’s second decade as CEO of the company – Nishat Chunian used the bulk of its cash flow for investments and capital expenditures rather than returning capital to shareholders, according to Profit’s analysis of the company’s financial statements.

Since 2008, measured as a percentage of EBITDA, Nishat Chunian’s investments in its subsidiaries, as well as direct capital expenditures, accounted for a far greater proportion of the use of its cash flows than dividends, even though the company has paid a dividend in all but one of those years.

However, over the past two years, dividend payments have outpaced investments, suggesting the company may be encountering some difficulty in finding profitable investments. That may at least partially be due to the economic slowdown experienced by the Pakistani economy, which has hit large scale industrial companies like Nishat Chunian especially hard.

Why the buyback?

The scale of the buyback – Rs1 billion worth of buybacks – is worth noting: it is larger than any dividend Nishat Chunian has paid throughout its history. And it would take 13.8% of the company’s shares off the market, effectively one-third of the free float of shares.

So, what is going on? Why has the company decided to pursue buybacks?

“The reason for our buy back from the stock market was that we had a PE [price-to-earnings] ratio of 2, which is ridiculously low. So, the best investment for us was to buy back shares. Our value subsequently rose 33%. We bought back at low prices, and eventually our shareholders made money,” said Shahzad Saleem.

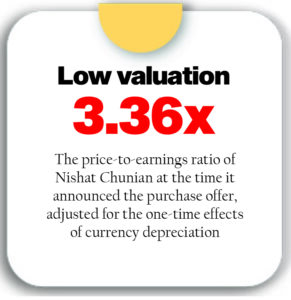

He is certainly correct: the market has been pricing Nishat Chunian stock unusually low, even when taking into account the fact that the earnings per share that Saleem cited as part of his price-to-earnings calculation was artificially inflated this year due to favourable currency gains that Nishat was able to take advantage of as a result of the massive devaluation of the rupee this past year.

Analysts and investors correctly conclude that such gains are likely one-off and do not represent ongoing profitability for the company. Still, even if one excludes that Rs1.4 billion in currency gains, the price-to-earnings ratio for the stock, a measure of its valuation, would come out to just 3.36 times financial year 2019 earnings. Nishat Chunian’s financial year ends June 30.

For context, the broader Pakistani market currently trades at 7.4 time trailing 12 months’ earnings, according to calculations by Topline Securities. Hence it is rational for Nishat Chunian management to feel that their stock price was being unnecessarily undervalued by the market, and that a stock buyback would be an efficient way to return capital to shareholders while also correcting what they felt was an anomaly in the stock price.

“There are two other things here: sometimes the valuation of these stocks is so low, and your market has fallen so much, that it is in the shareholders’ best interests to buy back stocks. That’s often the smartest thing for a company to do. And this happens all over the world,” said Shahzad Saleem. “The other thing is our tax structure. In Pakistan, there are low taxes on capital gains in Pakistan. So financially, it’s a good idea.”

Should buybacks be allowed?

Still the broader question remains: should buybacks even be allowed? After all, so what if the management feels that the stock price is too low? It is the job of management to operate the company efficiently and deliver revenue and profit growth and the communicate the prospects for that growth to the market. What the market chooses to do with that information is not necessarily something that the company should have any control over.

That used to be the position of regulators around the world. It was not until the early 1980s that the United States Securities and Exchanges Commission began allowing buybacks, and it was never quite intended to become the massively popular phenomenon that it has become in that economy.

Over time, however, regulators have come around the position that the Shahzad Saleem articulated: that buybacks are simply a tax-efficient way of returning capital to shareholders. While the Securities and Exchanges Commission of Pakistan (SECP) has allowed buybacks in the past, it articulated a fuller set of rules governing such transactions in March of this year, as a result of which it is easier for publicly listed companies to navigate the regulatory process.

Nonetheless, companies that have thus far engaged in buybacks believe that the regulatory process is still too cumbersome. “The mechanism for buying back shares in Pakistan is so illogical. The system is so full of rules and regulations, and is so bureaucratic. The process takes 45 days. But the stock market doesn’t wait 45 days,” said the Nishat Chunian CEO.

Indeed, is those regulations that have persuaded many that the negative side-effects of share buybacks – where CEOs use company money to pump up the value of stocks that then inflates the value of their own shares – are unlikely to become visible in Pakistan anytime soon.

When asked if he thought that buybacks will become a worrying trend in Pakistan, Shahzad Saleem responded; “No, [because it is difficult to do] with all these rules and regulations. The government should actually encourage this, for shareholders and minority shareholders. They need to amend the rules, and the timeline [of the process].”

As for whether there could be long term damage to the economy and the depth of the capital markets, Shahzad was equally sanguine: “Absolutely not. This is a matter of opportunity [opportunity ki baat hai]. Companies can always issue rights, or raise equity.”

With additional reporting by Meiryum Ali

Thanks, super informative article a layman like myself could easily understand! All the best.

Buybacks get a bad rap but as per most recent research by Ed Yardeni, buybacks have been mostly a tool to neutralize the dilutive impact of stock compensation for employees who would otherwise not have been participants of the stock market.

The management of Nishat Chunian is clearly exercising some of the soundest fiduciary judgement to be seen in corporate history globally. The company announced a buyback at a time when its stock was down well over 60% from its peak. And that the whole idea, make prudent use of capital – best of which, at current levels, being that you’re shares are trading at levels equivalent to distress, so buy them back.

Even Warren Buffett says he’ll buybacks if he sees Berkshire Hathaway shares below a certain intrinsic value.

Comments are closed.