“I’ve been out here all morning. Do you know how much I’ve earned so far? One hundred rupees.”

These are the words of a grizzled 50-year-old man, gruffly spoken through a mouth of missing teeth. His beard is white, his face is sunburnt and wrinkled, and his name is Sikander. Sikander will work up to twelve hours a day – his route will take him through sectors F and G in Islamabad. He will come home with a daily wage that barely sustains his nine children. His mother has died and his ageing father depends on him just as much as the children, none of whom are in school.

“School? Ha! I barely earn enough to feed them. Do you think I can send them to school?” says Sikander, with a wry chuckle.

“There is no place in Pakistan for the poor.”

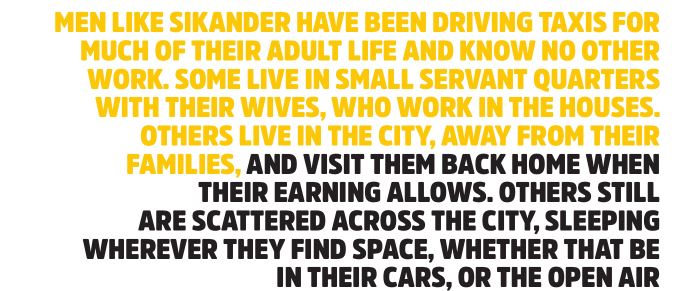

Men like Sikander have been driving taxis for much of their adult life and know no other work. Some live in small servant quarters with their wives, who work in the houses. Others live in the city, away from their families, and visit them back home when their earning allows. Others still are scattered across the city, sleeping wherever they find space, whether that be in their cars, or the open air.

“I’ve been driving a taxi for twenty years,” says Naseer Ahmed, a cabby in G-9. “I was earning roughly Rs40,000 a month. Now I’m lucky if I make half of that.”

Everywhere, the complaint is the same. The same conversation takes place over and over across the city, in dhabbas, at addas, and at shopping hubs like Centaurus Mall, where taxi drivers collate, hoping to catch the odd passenger who is not a Careem or Uber user.

“It’s made things harder,” says Arshad Shah, a taxi driver who has been at it for fifteen years now.

“The Careem people have a lot of advantage that we don’t. They can drive into the Red Zone, and we can’t. They don’t pay motor vehicle taxes either.”

Though it may sound simple, the taxi drivers’ conflict with Careem is complex. Increasingly over the past several months, a cloud of anger and resentment has seeped into the taxi driver’s psyche. If the loss of livelihood was not enough to compel them to act, Careem’s consequence-free operations were.

The taxi drivers allege that Careem is a taxi service provider and should be liable to the same laws and taxes that motor cabs and other public service vehicles incur. They argue the authorities do not compel Careem to abide by the law like it compels taxi drivers.

However, Junaid Iqbal, Managing Director of Careem Pakistan, defines Careem as a technology company that connects buyers and sellers. He outlines Careem’s first endeavour as connecting ride seekers to ride providers. In other words, Careem is simply a platform, and anyone is free to use it to get a passenger or a ride.

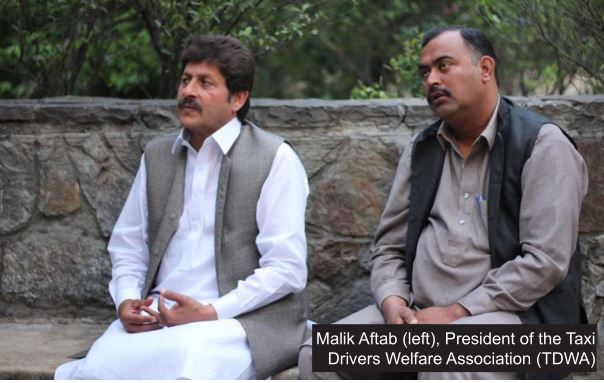

In August 2017, Malik Aftab, President of the Taxi Drivers Welfare Association (TDWA), filed a case against Careem and Uber in the Islamabad High Court (IHC), in violation of Section 34 of the Provincial Motor Vehicle Ordinance, 1965, which penalizes public service vehicles that fail to comply with motor vehicular law in reference to motor cabs i.e. cars for hire. While the hearing has concluded, Careem has obtained a stay order in reference to this case, and the final verdict has been delayed until further notice.

“The struggle of the taxi walas is the struggle of the working class,” says Umar Gillani, who represents TDWA in court, “and it has to continue, with a small chance or none.”

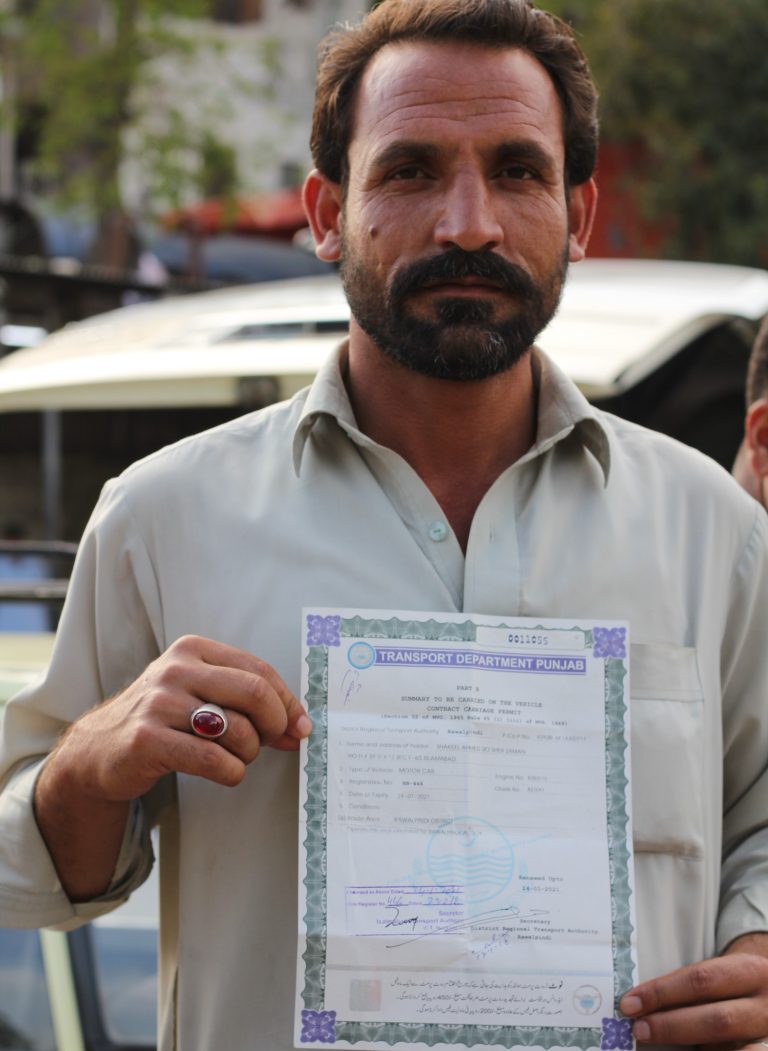

According to the Provincial Motor Vehicle Ordinance, 1965, all public service vehicles engaged in the carriage of passengers for hire or reward are compelled to obtain a permit from the Provincial or Regional Transport Authority (RTA), have a valid certificate of fitness, and pay the appropriate taxes levied under the Provincial Motor Vehicles Taxation Act, 1958.

According to the Excise, Taxation & Narcotics Control Department, Punjab and Excise & Taxation Department Islamabad Capital Territory, someone looking to drive a car for hire must pay the appropriate fee to first convert their private car into a commercial one. Applicants are compelled to pay a certain amount of money for the completion of this process, and that amount can be calculated on each department’s website.

Typically, this amounts to Rs8,000–9,500 for individual taxi drivers in Punjab and Islamabad. In addition to these initial taxes, drivers are also compelled to pay the token tax annually and pass the vehicle fitness test biannually. This can amount to Rs2,000 a year. Furthermore, drivers must apply for a route permit every three years. A route permit for Islamabad is not possible without obtaining a route permit for Punjab, and that can cost taxi drivers in Islamabad up to Rs1,200 every three years.

Under Section 34 of the Provisional Motor Vehicle Ordinance, 1965, any public service vehicle that fails to comply with the regulations outlined shall have its registration certificate suspended. Under Section 106, individuals who drive a motor vehicle or allows a motor vehicle to be used without the appropriate permit will be punished with imprisonment for a period of six months or with a fine that extends to Rs500.

The Ordinance has defined the term “public service vehicles” as “any motor vehicles used or adapted, to be used for the carriage of passengers for hire or reward, and includes a motor cab, contract carriage, and stage carriage”. “Motor cab” refer to any motor vehicle used to carry not more than ten passengers, for hire or reward.

The definition “motor vehicle for hire” is loose enough to include Uber drivers and Careem Captains, if not the companies themselves. Careem already separates its work from that of Captains, by identifying itself as a technology company. Regardless, the work of Captains remains the same. They drive for hire.

Junaid Iqbal, however, insists that Careem Captains fall outside of this definition. He believes Captains engage in ride-hailing, which refers to booking a car using an online platform. He argues that ride-hailing is a new phenomenon, introduced seven years ago by Uber, and commercialized by Careem in Pakistan.

“There’s no paperwork for ride-hailing,” insists the Careem supremo.

The distinction between ride-hailing and taxi driving seems to be that ride-hailing uses an online platform to book a car for hire, while taxi driving does not. Is that a good enough reason for the government to exempt Careem Captains from paying motor cab taxes? Or for Careem to resist classification because the legal definition is not precise enough? Or does it warrant new legislation altogether?

Even if Careem self-identifies as a technology company, Careem knowledgeably and routinely signs Captains who do not comply with motor vehicle legislation with respect to motor cabs. Careem maintains Captains are self-employed and merely use the platform to find passengers, but Careem regulates Captains signed onto its platform. Captains are prohibited from smoking in the car, driving above 40 km/h, and can seat no more than 4 passengers at a time. Captains who face complaints or consistently poor ratings are penalized and retrained to adhere to Careem standards.

“Khaadi has to abide by the rules of Dolmen Mall,” says Iqbal, “Similarly, Careem is a virtual market place and we have to manage it.”

If Careem is indeed the Dolmen Mall to these drivers’ Khaadi, the question becomes – why won’t Careem take its regulations a step further and compel its drivers to abide by the existing laws and taxes that concern motor cabs?

“Regulation affects supply,” says a Careem employee, who has asked to remain anonymous. He believes that compelling Careem to abide by legislation that pertains to motor cabs will affect the number of people signing on to Careem’s platform as ride providers. Ultimately, he says, that will impact Careem’s growth, a company he argues, that is still in its nascent stages and has just broken even.

The employee believes that unregulated, Careem is doing more good than harm. He argues that Careem has ambitions that would continue to see the country benefit from its operations. Over the last two years, Careem has worked with The Citizens Foundation (TCF) to generate donations to build schools. Most recently, Careem announced its partnership with Edhi Foundation to provide ambulance services in the country. Karachi customers of the ride-hailing app can now make a ‘later’ booking for the service by clicking on the ambulance category.

“Careem should not be regulated right now,” he asserts.

Following the formal question of its legality in January of last year, Careem has been hinting at working with provincial governments to develop new legislation that would incorporate e-commerce companies like Careem into the tax bracket. Iqbal says that so far, there has been an agreement on the broad principles on which legislation is to be based. He also claims that Careem is on the verge of signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with at least two provinces, but that does not mean an agreement has been reached with RTAs. Careem’s previous MoU had been signed with Punjab Information Technology Board (PITB), not the PTA.

Iqbal reasons that European countries have poured significant investments into public transport. Regulations against companies like Uber and Careem protect their investments. Countries like Pakistan, however, where public transport investments were near to non-existent until recently, stand to benefit from private sector investments.

“That makes regulation more unfavourable,” says Iqbal.

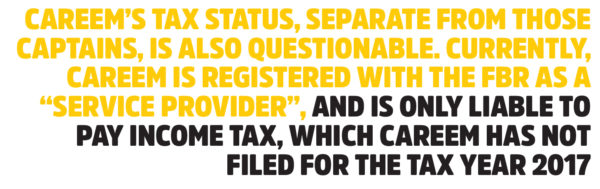

Careem’s tax status, separate from those Captains, is also questionable. The 2017 Finance Act improved on the Income Tax Ordinance of 2001, and introduced the concept of an online marketplace, which the Act further defined as “an information technology platform run by an e-commerce entity over an electronic network that acts as a facilitator in transactions that occur between a buyer and a seller”. In Section 2, 38B, the Act compels such platforms to pay an income tax of 0.5% and sets the rate of collection of advance tax on brokerage and commission on an online marketplace at 5% for the Tax Year 2018.

Currently, Careem is registered with the FBR as a “Service Provider”, and is only liable to pay income tax, which Careem has not filed for the Tax Year 2017. While Iqbal says that Careem is in the process of being regulated, he issued the following statement in relation to further questions about taxes and regulation:

“We are currently engaged with authorities at the provincial and federal level regarding how e-commerce platforms will be regulated and taxed, hence it would not be right for me to comment on specifics at the moment. Having said that, the process is moving swiftly and we have excellent support from all quarters of the government.”

Without a policy to protect them and with the weak exercise of legislation compelling them, taxi drivers have made multiple attempts to pressure the relevant authorities to compel Careem to pay these taxes, but to no avail. In December 2016, the Taxi Drivers Welfare Association (TDWA) lodged a complaint against taxi companies that were operating without permits. According to a report by Dawn, the Islamabad Transport Authority (ITA) raised and sealed these taxi companies’ offices, including Careem’s.

In late January 2017, the Punjab Government’s Provincial Transport Authority (PTA) announced that ride-hailing services, Careem and Uber, were found to be in violation of motor cab legislation. They were given 15 days to register their cars with the appropriate regulatory bodies and acquire a vehicle fitness certificate. In response, Careem lobbied for legal reforms that Careem felt would incorporate the company into the tax-paying fold.

The PTA, for its turn, compiled a report with regard to Careem’s operations in the country. The report, which maintains that Careem is operating illegally, was passed on to the Punjab Chief Minister. The report claims that Careem is neither willing to pay the required taxes, nor colour nor commercialize their cars. No formal action was taken after the 15-day period, despite Careem’s non-compliance. An official at the PTA, who wished not to be named, believes that no action has been taken because of Careem’s multinational stature, and because of consumer demand.

By August, taxi drivers in Islamabad had begun to protest at Rawal Dam Chowk. The primary purpose of the protest was to force action against ride-hailing apps, which were impacting their daily wages. Malik Aftab, President TDWA did not participate in the protest, given that he had already filed the writ petition against Careem and Uber in the IHC.

One of the taxi drivers’ major complaints is that despite paying numerous taxes, they do not receive any benefits or social security from either Punjab Employees Social Security Institution (PESSI) or ICT Employees Social Security Institution (IESSI).

“In order to qualify for social security, units must be registered with the IESSI,” says Raheel Bashir, Assistant Director Recovery, IESSI, “Currently we have 1,110 registered units under which 36,000 secured individual workers are registered to receive social security.”

Basheer says that it is mandatory for all operating units – organizational bodies – to register. Only non-government organizations and government institutions are exempt. Units must consist of at least three workers to qualify for social security, but because the majority of taxi drivers are self-employed, they do not qualify for social security with either institute. PESSI operates in a similar way that excludes taxi drivers from benefiting from social security.

Interestingly, Careem and Uber are both registered with IESSI, which qualifies their employees for social security. Whether that qualifies Careem Captains for social security is difficult to say, considering that Careem has always maintained that Captains are independent contractors.

Careem’s service category “Careem Taxi” further compounds these issues. Does Iqbal’s assertion that Careem Captains engage in ride-hailing apply to Careem’s Taxi Captains, too? If so, does that exempt Careem’s Taxi Captains from paying their taxes? Request for answers to these questions was not granted.

Careem’s ambition may have been to address taxi driver complaints by incorporating them into Careem’s service categories. The hope was to entice taxi drivers with a consistent surplus of demand (passengers) leading to an increase in net income, in exchange for a 30-70 split on earnings.

Despite the effort, Careem’s payment structure does not appear to be lucrative for taxi drivers. A typical taxi driver will keep most of his earnings, but with Careem Taxi, he is liable to pay around 30% of his earnings to Careem. Careem’s bonus structures do offer him some leeway, in that the split may become roughly 20% to Careem and 80% for himself. However, because he is still under obligation to pay motor vehicular taxes, and is often harassed for bhatta (illegal extortion) by rogue police officers, the average Careem Taxi Captain is still struggling to make ends meet.

Of course, taxi drivers can privatize their commercial cars – that would seem to solve the aforementioned contradiction, but it would be foolish for Careem to compel them to. PTA and ITA still consider Careem cars illegal and because their cars are easily identifiable, taxi drivers will be held accountable before anybody else.

“I worked for Careem Taxi for a few months,” says Liaqat Hussain. He says that Careem scouts would wait at addas and stops in attempts to recruit taxi drivers. Twice, he says, they approached him, before he relented and signed up with them.

Hussain says that the only advantage a Careem Taxi Captain has is the opportunity to earn a bonus, separate from his daily wage. Careem encourages its Captains to stay online and take rides by offering bonuses. If a Captain can achieve a certain number of rides a day, he/she will receive a bonus from Careem. Hussain alleges that when he first signed up, the bonus structure was designed such that it seemed easy to achieve. Within twenty days, the structure changed. Soon after, it changed again, making the now seven-rides-a-day goal challenging. Eventually, he says, in a two to three-month period that he worked as a Careem Taxi Captain, it became impossible.

“I quit soon after,” says Hussain, “It didn’t suit me.”

Hussain says the average taxi driver is lucky to get ten rides a day. By the time he quit, the daily bonus goal had become twelve rides. Working as Captain, he was earning the same amount he had been earning as an average taxi driver. Even though he was taking more rides, he was still taking home less money because of the 30-70 split with Careem. The continuous instability of the bonus structure and the pressure to stay online constantly also dissuaded him from continuing to work as a Captain.

“The Captains are not happy with the new bonus structures,” admits the anonymous Careem employee. Captains like Zeeshan Abbasi state that it is impossible to make a living as a Captain without the added advantage of a bonus. Increasingly, bonus structures have proven to be erratic and unfavourable, changing as early as seven days or as late two months, with targets that many Careem Captains feel are difficult to achieve.

In recent months, Careem Captains and Uber drivers have launched their own protest against the technology giants, citing unfair bonus structures and customer behavior as key motivators.

“They’re only interested in customer care,” says Zeeshan Abbasi, a Captain, “They don’t care about how the customer treats us. If I don’t want to take my car into a dark narrow alley with bumps and potholes, I shouldn’t have to – but if I don’t, the customer complains or rates me badly.”

Another reasons taxi drivers will not join Careem is that in order for Careem to work smoothly, Captains have to stay online so passengers can avail rides. The average taxi driver can refuse a ride without complaint, depending on whether he’s resting, eating or has fulfilled his personal quota for the day. Careem Captains, however, are under pressure to stay online in constant pursuit of an unachievable bonus, or even by the vendor they work for.

The Careem Captain protest has spilled onto social media. Careem’s Twitter account is flooded with complaints about a constant “peak factor” that will not relent. Careem’s peak factor is an automatic feature of the app, when demand for rides is high, but Captains available are low. Rides taken during Careem’s peak factor are typically charged more – another motivational technique for Careem Captains to stay online. The peak factor complaints on Careem’s Twitter page coincide with the Captains’ protests.

“I will never join Careem Taxi,” says Sikander with a defiant shake of his head, “Never. I would rather starve and die, earning nothing, than join them.”

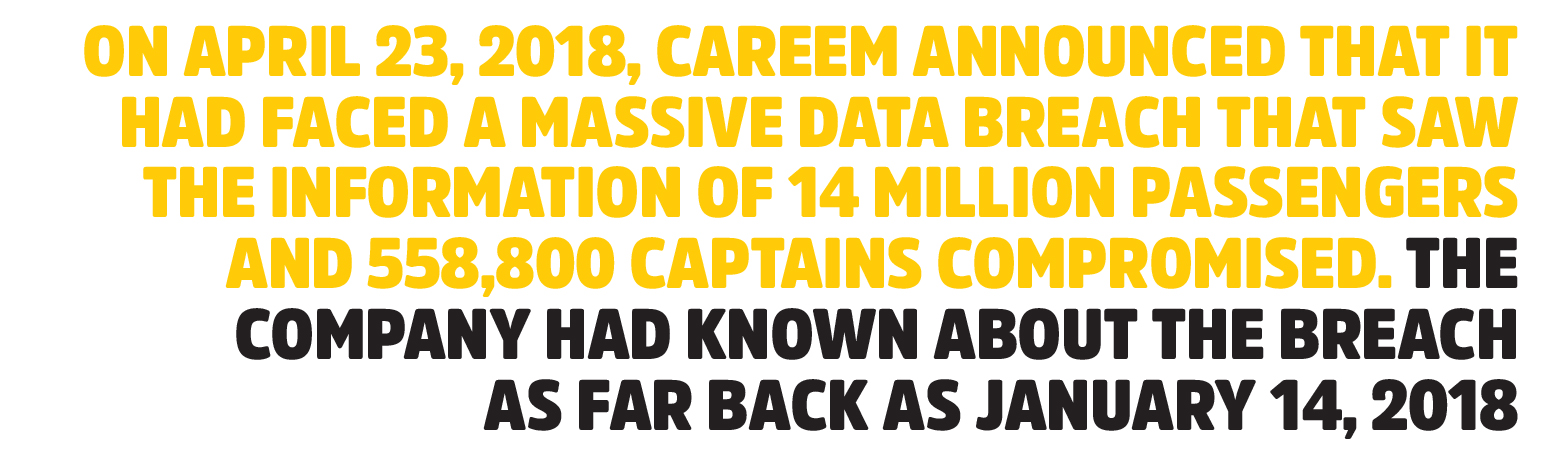

This is not the only issue Careem has faced recently. On April 23, 2018, Careem announced that it had faced a massive data breach that saw the information of 14 million passengers and 558,800 Captains compromised. The company had known about the breach as far back as January 14, 2018, and chose to contain the information to “make sure we had the most accurate information before notifying people”.

Malik Ahmed Khan, Member of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform, believes that companies like Careem need to be more transparent in the way they operate, particularly since data and privacy are key issues where Pakistan really does lag in terms of legislature.

He also believes, much like the PTA and ITA, that Careem and Uber are taxi companies that are technology-sophisticated. Khan says that with the companies’ arrival, the market is now offering something comfortable and secure, with better services, at cheaper rates and that attracts customers, more than anything else.

“It’s consumer choice,” explains Khan.

That Careem should thrive in a marketplace with limited options is no surprise. The platform’s biggest appeal for drivers and passengers is that it connects the two directly, making the process of catching a ride hassle-free and comfortable. Careem also offers an air of respectability to class-conscious ride seekers who do not want to be seen in a yellow Suzuki Mehran. Additionally, Careem’s security measures, such as providing passengers and drivers alike with a profile of the other and tracking routes, enhance its appeal, particularly for Pakistani women. Careem claims that 70% of its passengers are female.

More than that, historically, Pakistan’s public sector has always failed to meet the capacity of the country. Again and again, the private sector has been encouraged to fill the vacuum of the public sector’s failings. Specifically, the Pakistani government has a long history of encouraging private sector involvement in public transport.

Muhammad Ian of Massey University, New Zealand, charts the history of public transport in Pakistan in his paper, titled, “Public Transport in Pakistan: A Critical Overview”. In the paper, Ian writes that in the first few decades of Pakistan’s independence, despite private sector involvement, the public sector had monopoly over the public transport system. In the 1970s, public transport was deregulated, which allowed the private sector to compete with public-owned bus services. Further policy changes saw the development of incentive packages specifically to lure private sector investment in public transport.

For example, the National Transport Policy of 1991 offered soft loans, reduced custom duty and tax incentives for private investors. Similarly, the Prime Minister’s Incentives Scheme to Revamp Public Transport Scheme from the same year outlined incentive packages to import taxis, buses, and minibuses duty free. It also encouraged loan arrangements from banks and allotted special registration numbers for public transport. By 1999, the government was still involved in public transport regulation, but operational duties were left to the private sector.

While the public sector has made a comeback of sorts with the Metrobus project for inner-city transport, public transport remains unregulated and largely in the hands of private sector entities and individuals. This includes taxi drivers.

Khan argues that in the absence of strong policy and regulation, taxi drivers have gone unchecked for too long, and that has resulted in drivers exploiting passengers with unpredictable fares. He also argues that taxi cabs must be fitted with meters that calculate fares based on specified rates. Typical Pakistani taxis do not adhere to that standard, even though the Motor Vehicle Ordinance, 1965, compels them to. It also compels them to display a table of fares on the vehicle.

“There is an under-regulation on part of the municipal authorities,” admits Khan, “but the taxi drivers don’t want to be regulated either.”

The Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform is currently working on a new transport policy that it hopes to introduce by the end of the year. Despite this, because of the 18th Amendment of 2013 which saw the redistribution of power to the provinces, Khan believes it will continue to be difficult to regulate either Careem or taxis in a uniform way, because the responsibility lies with the provinces and municipal authorities.

Khan’s statement about consumer choice does not seem to have resonated with the government. On April 22, 2017, the Punjab government announced its plans to launch the Orange Cab Scheme, which would see the distribution of 100, 000 cars on the basis of soft loans. The purpose of the scheme, like many before it, is to provide job opportunities to the country’s unemployed youth, but many taxi drivers do not feel that enough is being done.

“They should offer us opportunities that would level the playing field,” says Naseeb Ullah, a taxi driver who operates part-time in Rawalpindi and Islamabad. He had been working privately for a family until late 2015, when he decided to drive a taxi. Unlike most taxi drivers, who take loans to buy their cars, the family he worked for helped pay for his taxi, loan-free.

Interestingly, the first Yellow Cab Scheme launched during Nawaz Sharif’s government in 1993, distributed cabs that offered air-conditioned taxis and had electronic meters to calculate fares. Various factors, including government instability, policy changes and misuse of cars, saw that the scheme did not succeed.

In 2011, the Punjab government, under PML-N leadership, announced that it was reviving the Yellow Cab Scheme. While it was more successful than its predecessor, the tail-end of the loan repayments from the Yellow Cab Scheme of 2011 coincided with Careem’s official launch in March, 2016.

“They had spent five years paying off those loans,” says Naseeb Ullah, “They had just started to earn for themselves. Then Careem came. We started losing money again.”

Many taxi drivers are skeptical that the Orange Cab Scheme will make an impact. The cars distributed in the latest iteration of the Scheme – typically Suzuki Mehrans, Bolans and Ravis – will not compete in a Post-Careem marketplace that prioritizes comfort, security and innovation. Their problems will remain the same, and their daily wage will not improve.

“Whenever a new government comes in,” says Aftab, President TDWA, “They use the taxi drivers like tissue paper and then throw them away. The Scheme is nothing but a business.”

Aftab believes that in order to compete with Careem and Uber, it is imperative that taxi drivers embrace technology. Aftab’s Taxi Drivers Welfare Association launched The Safe Taxi app in January, 2018. It claims to be the first legally run cab service app in Pakistan, with a registered list of taxi drivers with approved licenses and permits. Currently, it is available for download.

“The Safe Taxi app will protect both drivers and passengers and it will run legally,” says Aftab.

Aftab hopes that the Safe Taxi app will allow TDWA to segue into other issues that fall upon taxi drivers, like that of welfare and education. He also hopes to work with taxi drivers on improving their services so that they can compete with Careem and Uber.

Careem’s biggest economic contribution has been job creation. Out-of-work, young people with university degrees use the platform to make money and experienced drivers appreciate the app for reducing the hassle in acquiring passengers. Many of Careem’s registered cars belong to individuals who have invested in car fleets to start their own vending business. Still, many taxi drivers see Careem as a threat towards their way of life.

“He’s literate, he has an education,” says Naseeb Ullah of the typical Careem driver, “He’s not at a loss for anything in life. We’re in mazdoori. We have more right to earn a living this way.”

The larger grievance seems to be that opportunities seem far and few in between for people like Naseeb Ullah, Sikander and Hussain. The young people driving Careem’s growth will move onto other things – better jobs with career growth – but taxi drivers, like many of Pakistan’s disenfranchised, will continue to toil as they have for years. In the absence of strong government policies that develop competitive opportunities and protect their livelihood. Many seem resigned to their fate, and aspire to no more than a return to a good day’s wage.

Sooner or later Careem would be out of market like yellow cabbers taking a knockout at the hands of Uber. Private rent a car type business cant be regulated in Pakistan where most of officials are bribe Hungery.

Thanks.

Many drivers are selling their cars purchased on loan from banks at throw away prices to Afghanis or to local Kabuli spare marketers. We can’t see any yellow cabs given by Sharif Govt. All gone to Afghanistan or black market. 2019 year would a disasterous year for banks and insurance companies on account of the loaned cars.

Thanks.

An ex- uber driver

There is one way for Careem to survive in Pakistan. Adaptability.

Careem can’t survive in PAKISTAN where uber allows to cancel unwanted rides but Careem impose fine of 1000 rupees. That’s why careem can’t survive in PAKISTAN.

Comments are closed.