In 2001, when Umar Saif arrived at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for the first time in his life to deliver a lecture, he was dealt with a surprise. The university, one of the best in the world, essentially had a relatively small urban campus, especially when compared to his alma mater at the University of Cambridge and even his high school, Aitchison College.

“It was raining on that day and I had to reach the fifth floor of the building to deliver a lecture. The lift was out of order, so I had to take the stairs. By the time I started speaking, I started to recognise people in the audience as I had read text books written by them. There was a person who had invented RSA, a person had written the first operating system. Those were the kind of people that were present in the audience.”

That was the day Saif realised that MIT was not what it was because of the facilities that it offered or its campus, but what made it great was the kind of people there, students and staff alike. In the 153 years it has been in existence, MIT has produced some of the best minds in all of human history, including 93 Nobel laureates, 25 Turing Award winners, and 8 Fields Medalists who have been affiliated with MIT as alumni, faculty members or researchers. In addition, 34 astronauts and 16 Chief Scientists of the United States Air Force have been affiliated with MIT.

That experience in 2001 set the inspiration for Umar Saif to set up an MIT-like university in Pakistan, which could produce people who could impact the world at large. An inspiration, and perhaps the successful incarnation of what was once a dream is reflected in the fact that Saif’s brainchild, Information Technology University (ITU), does not have a campus, and is established only on two floors inside a government-owned building on Lahore’s Ferozpur Road, but has already started making an impact despite being in the nascent stages of its existence.

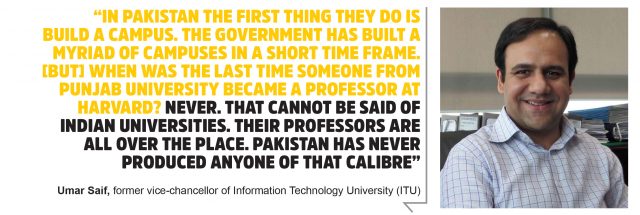

“In Pakistan, the first thing they do is build a campus. The government has built a myriad of campuses in a short time frame,” Saif said, insisting that the priority should be focused on attracting competent human resources instead. “When was the last time someone from Punjab University became a professor at Harvard? Never. That cannot be said of Indian universities. Their professors are all over the place. Pakistan has never produced anyone of that calibre.”

A research-oriented university

The original purpose of a university is to impart and produce new knowledge and be the guardian of reason, a sense that has been lost to the struggle for social mobility. The situation is particularly worse in Pakistan. Creating new knowledge has never been a purpose of Pakistani universities, according to Saif. Historically, universities have very quickly degraded into teaching colleges, only left with a purpose of teaching a very large number of students.

“They never aspired to become universities,” he argued, stressing that the universities’ mainstay is its faculty and the faculties’ ability to produce independent knowledge: in essence, research.

Saif sees that as a lack of vision on part of the government as there was no policy aligned with promoting and encouraging research at universities. Why? Because universities were used as bastions of political power, turning students into political mercenaries rather than scholars.

“The biggest gangsters used to live in universities and arms would be recovered from the campuses. So we politicised and weaponised the university students for our political gain. Politicians extracted what they wanted from the universities and then just let them be,” he said.

It is fairly easy to observe, and to speak from experience, that during the time a student invests at a normal Pakistani university, there is nothing different over the course of four years except getting taught trivial courses in an equally trivial manner. So how is ITU different?

Out of the 112 faculty members working at ITU, 86 hold a doctorate degree and are given full liberty to focus on research. “The faculty members only teach one course per semester. How can you expect someone to do research if they are teaching seven courses in a single semester? In addition, they get all the facilities for conducting research,” he said, adding that even the PhD students are paid a monthly stipend of Rs80,000 for research.

Hassaan Faisal, an ITU student enrolled in the Data Science programme, said that he chose ITU for a masters because of its faculty. “The amount and quality of research here convinced me not to go abroad. The level of teaching, the curriculum is all up to the mark. I think I made a good choice joining this institute. It is different here, students are valued.”

Traditionally in Pakistan, university faculty members have been reluctant to work under an evaluation framework, that has led to a deteriorating standard of higher education. “Even if a tenured track pays more, people teaching in universities are scared of the accountability and would rather opt to work as a lecturer earning Rs75,000 a month as it is a pensionable job,” said Saif.

Even if the university management is able to convince the faculty to work under an evaluation framework, they run the risk of getting deceived. “The professors start gaming the system. In Pakistan, there are lots of embarrassing stories. The professors start their own journals and publish plagiarized papers. Even If they get caught, you cannot fire them, because they hide behind the protection of court or a political party. Hence, Pakistani universities were destroyed and are non-entities internationally,” he said.

In contrast, ITU’s faculty gets the support they need to travel, to buy equipment and to hire people from the market for research, promoting an environment more conducive to research, structured more like MIT, as Saif envisioned. Moreover, the faculty has no constraints on how to perform, are independent and hired on a tenure-track system. “They get a six-year clock within which they have to publish a top-tier conference or journal in their field twice.”

A testament to ITU’s research endeavours was this year’s Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), considered the most prestigious in the field of human-computer interaction and is ranked one of the top conferences in computer science, published four papers from Pakistan, all from ITU. “One of those papers is the second highest rated paper in the entire conference, out of about. 2,500 submissions,” a visibly excited Saif said.

But research is expensive and not many universities in Pakistan are able to spend a significant amount of money on it. Unlike Pakistan, universities in the United States are usually supported by endowment funds, financed by philanthropic donations from family foundations. Billionaires, as an act of philanthropy, create foundations which then support Stanford, Princeton, and the likes of them.

“We are very charitable in Pakistan but we have hardly any family foundations. Most [wealthy] people hand over their wealth to their kids when they die. All the [major] American universities run on the support of these foundations. All these foundations have put money into the endowments of these universities and [some of] their endowments are bigger than Pakistan’s whole budget.”

Currently, ITU does not have any privately funded endowments but has a Rs500 million endowment fund that has come from the government. But no one spends this money and it keeps adding up as a saving of the university to help it in the time of need.

The spirit of entrepreneurship

A study commissioned by MIT in collaboration with BankBoston in 1997 summarised the impact the MIT alumni had on the world, and one of the indicators they had was their entrepreneurial skill. The report noted that the 4,000 MIT-related companies employed 1.1 million people and had annual world sales of $232 billion. If all the companies founded by MIT graduates and faculty formed an independent nation, the revenues produced by the companies would make that nation the 24th largest economy in the world. That is roughly equal to a gross domestic product of $116 billion, which was a little less than the GDP of South Africa and more than the GDP of Thailand.

Building on the same spirit, Umar Saif says that ITU’s culture has been ingrained with entrepreneurship. Our professors are also entrepreneurial. “We have a policy here at ITU according to which anything that the professors invent is yours. The university has no right over their intellectual property. Pakistan needs innovative ideas to form new companies. It does not need ITU’s ownership of intellectual property, which other universities require of their professors,” said Saif.

“Even our professors are encouraged to be entrepreneurs and they own their intellectual property. They get one day off a week from the university to do consulting, work in the industry or work on their own entrepreneurial ventures. Several of them have their own companies going on.” Almost 85% of ITU’s first batch of graduates was hired by companies owned by ITU’s own faculty members.

And then there is Plan9, Pakistan’s first and the fully organised tech incubator, located in the same building as ITU, nurtures and provides the students with a platform to develop their entrepreneurial ideas. Plan 9 has thus far graduated over 160 startups with their collective valuation standing at almost $70 million.

But not all graduates venture into their own startups. There are some graduates who choose to enter the job market, hoping to work with established giants in the tech industry for a lucrative career, as IT jobs are considered to be fairly well-paid.

Profit reached out to software firms to get an idea about their preference when it comes to ITU graduates compared with old universities such as FAST and NUST.

A software company in Pakistan, considered to be among the top firms in the country with a global presence, disclosed that it preferred graduates from FAST and NUST over ITU and LUMS graduates, for entry-level positions.

Another employer, also considered to be among the top names in Pakistan’s IT industry, disclosed that they do not have a specific preference of graduates from a particular university, but revealed that the number of applicants to their firm from ITU was far less and there was no ITU student working with them at present.

It is pertinent to note, however, that only two batches of students have graduated from ITU since its establishment in 2012, so the number of applicants from ITU would understandably be far less than other established universities. Surmising that ITU does not have a fair share in the Pakistani IT industry related jobs will, therefore, be premature.

A recent graduate of ITU told Profit that employer preference in the IT industry is based on the skills, academic record and the work a graduate has done. Being among the graduates of the only two batches that have graduated from ITU so far, he said that they bear the responsibility of building the preference among employers for ITU graduates, based on the work they’ll deliver.

Interestingly, he revealed that he was also working on two startups, corroborating with Saif’s claim of inculcating entrepreneurship among ITU students. “It’s not just me, many others from my batch, and even my juniors are working on startups.” He, however, lamented that not everyone can be an entrepreneur so for those who struggle to become one and prefer doing a job, there are no formal career placement programmes in the university.

While the university aspires to be Pakistan’s MIT, it is currently without a head after Umar Saif’s abrupt removal from vice-chancellorship by the new Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government in Punjab. The problems have already started emerging. A source told Profit that the university has now been operating without a head for over a month, which is a bad omen. Many of the contract employees have been forced to leave due to the non-renewal of their contracts, which requires a vice-chancellor’s approval. To make things worse, the government is still mum over appointment of a new VC.

In Umar Saif’s own words, the ITU faculty, most of whom came to Pakistan because they valued the ideals behind ITU, if that changes drastically, many of them might not want to stay. “Building institutions is very difficult, destroying them takes one notification,” he said.

Kodos to ITU. I

I remember two gentlemen, doctorate from MIT in the field of Chemical Engineering, Dr Allahwala and Dr Ahmed Shah Nawaz, both played pioneering role in the establishment of oil refineries, fertilizer and chemical projects as consultants, both in West Pakistan and East Pakistan, under WPIDC and EPIDC and other private sector projects starting their career from early sixties onward. I have the honour serving with Dr Ahmed Shah Nawaz in his company Chemical Consultants (Pvt) Ltd Lahore for quite some time.

Dr. Umer should be reinstated. Government should not mess with some thing going good already.

The Tehreek e Insaaf government is rapidly revealing itself to be an authoritarian outfit requiring absolute submission, particularly from those who pride in their competence and integrity. It seems to be setting off on a track which may suit the ambitions of its elite but may destroy institutions like the IUT which have pursuit of excellence as their mission. Very sad. Very disheartening.

Comments are closed.