The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government is not gathering many successes on the economic front. In February, the inflation rate reached its four-year high at 8.2 percent as the impact of constant Rupee devaluation finally hit Pakistan’s import-dependent economy.

According to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) showed a 7.19 percent year-on-year increase and the last time inflation reached 8.2 percent was in June 2014. So, what is it about then and now that is similar? It seems that we are seeing the making of another tax amnesty scheme. Prime Minister Imran Khan met members of the traders’ community on March 4 and sought suggestions regarding a potential scheme.

Before delving into the merits and demerits of having another “financial NRO” and what to expect if it comes forth, let’s take a look at some of the previous amnesty schemes and the impact that they had on tax collection and the overall economic situation of Pakistan.

Let us begin by admitting that such schemes invariably end up discouraging and hurting actual taxpayers in favor of tax evaders. They also hurt the national exchequer when seen in comparison to tax collection during the absence of such amnesty schemes. “[Another amnesty scheme] is absolutely unnecessary and useless,” says Nadeem ul Haque, former deputy chairperson of the Planning Commission Pakistan. “It should be a thing of the past. Government needs a good tax policy. Tax amnesty schemes only show that you have no ability to make a policy or carry out its administration.”

History of amnesty schemes and their failures

A tax amnesty scheme, in its most basic sense, is a voluntary compliance strategy that allows individuals or organizations who have not paid their taxes previously to pay a certain amount during the scheme to avoid criminal prosecution. It is meant to help state treasury departments raise tax revenues and widen the tax net, but in effect it mostly ends up benefiting tax evaders at the expense of taxpayers.

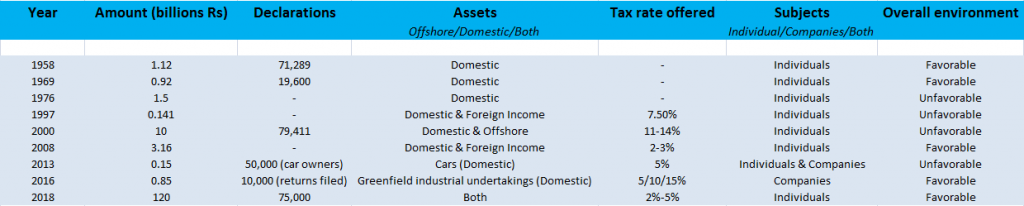

Pakistan offered its first tax amnesty scheme in 1958 and since then, there have been more than a dozen amnesty schemes with successive governments promising almost each of them to be the last. Details of some of these schemes are hard to find and probably lost in a plethora of documents that may or may not exist. For instance, the schemes of 1985, 1991, 1998, and 2012 are remembered only in name with no details on tax rates, declarations filed, or revenue generated. No data is available with the State Bank of Pakistan, the Federal Board of Revenue, or the Ministry of Finance for these schemes. For those schemes that have data available, we have compiled it below:

The first tax amnesty scheme was introduced during the regime of Ayub Khan towards the end of 1958. It brought approximately 71,000 declarations and as many as 266,183 taxpayers entered the fold contributing a total of Rs1.12 billion. Despite this, tax collection remained at less than 10 percent of the total GDP in 1958-59.

“Black economy” and untaxed economy has always been part of Pakistan’s economic problems, but the intensity of the issue has been constantly deepening with every passing regime. According to research conducted by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) in the late nineties, the underground economy was approximately 4% of the formal economy in 1983 and had worsened to approximately 40% by 1997. In monetary terms, the report valued informal economy to be $15 billion and $1,215 billion in 1983 and 1997 respectively. Considering this figure, the Rs141 million collected through the 1997 tax amnesty scheme shows inconsequential impact of the scheme.

The 2000 amnesty scheme, perhaps, holds more importance for the current regime than any other because the current prime minister was himself one of the beneficiaries of the tax amnesty scheme introduced under the Musharraf regime. Khan declared his London flat that he had bought some eighteen years ago in 1983. Along with him, approximately 79,000 other declarations also came forth in that year’s tax amnesty scheme contributing a total of Rs10 billion in tax collection. It is even more interesting to note that later, in 2013, Imran Khan became one of the fiercest opponents of tax amnesty schemes. And now, as the prime minister, he is considering another scheme. We will discuss Khan and his party’s inconsistency in policy making later.

Then, in 2013, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) announced another scheme. Dealing only with assets held within the country, like the 1997 scheme, this too was focused on appeasing a select voter base. This scheme was primarily for owners of imported cars who had brought them into the country without paying due taxes. The estimations of the loss from this “black market” activity was Rs35 billion. The calculated tax as a result of the amnesty scheme, however, was less than 1% of this value.

The 2016 scheme was also directed at the same economic strata of society, aimed at pleasing small traders by offering tax exemptions as well as immunity for the financial crimes committed previously as long as they were prepared to bring their domestic assets into the legal fold. The targeted community was not very willing to avail the scheme and only a mere 10,000 declarations were made, contributing Rs0.85 billion.

2018’s exception and external factors

To date, the most successful tax amnesty scheme, if measured purely in terms of revenue collection, is the 2018 scheme that was introduced by the PML-N government. This was the first scheme by PML-N that dealt with not just local but also foreign assets. The only other relatively successful amnesty scheme was the one announced by Pervez Musharraf which also allowed for declaration of assets abroad as well as domestic holdings. This might be indicative of the fact that those who do not pay taxes on their international properties are more willing to be included into the tax fold, as compared to those who have found loopholes in the taxation system in Pakistan which allow them to maintain properties in the country without becoming filers.

On April 8, 2018, then-president Mamnoon Hussain promulgated four ordinances to affect a one-time amnesty scheme for “legalizing” undeclared assets at home and abroad, a reduction in income tax rates, issuance of dollar-denominated bonds and restricting cash transactions in non-filer accounts.

The tax rate offered for foreign currency accounts within Pakistan was 2% while for other assets a 5% tax rate was offered. For foreign assets, the non-repatriated liquid assets tax rate was 5%, for immovable property outside Pakistan it was 3%, and for repatriated liquid assets the tax rate was 2%. The tax rate for liquid assets repatriated and invested in government securities – up to five years in US Dollar-denominated bonds with six-monthly profit payment in equivalent Rupees (rate of return 3%) and payable on maturity in equivalent rupees – was also 2%.

This scheme resulted in an unprecedented repatriation of money and declaration of assets, amounting, to approximately Rs120 billion, according to initial estimate by the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR). However, there is one more factor to be considered that might as well have been the factor for success of this amnesty scheme: by the time this scheme was announced, the maintenance and security of undeclared wealth abroad had become a lot more dangerous than ever before and governments globally had been collaborating to bring undocumented wealth into the legal fold.

Pakistan has become a signatory to the OECD Multilateral Convention which had been open to providing access to information about offshore financial accounts of Pakistani residents from September 2018. A direct impact of this is towards enhancing the capacity of the FBR which can now gain access to offshore financial accounts of Pakistani residents held in signatory countries. Furthermore, amendments were also made to the Protection of Economic Reform Act of 1992 to regulate foreign exchange movements and bring them in line with the Income Tax Ordinance of 2001. By way of these amendments, the FBR may inquire about the source of foreign remittance above Rs10 million and a limitation of five years to probe foreign assets and income has been removed.

What can be expected from the PTI government?

Currently, Pakistan faces the daunting task of cracking down against tax evaders. Only 1.3 million people file their annual income tax returns and even fewer pay the due amount of taxes. According to FBR reports, the direct tax collection is less than 40% of the total tax collection and most of it comes from over 75 types of withholding taxes.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also assessed Pakistan’s gross external financing needs at its highest, at $27 billion, for the current fiscal year. It is notable that the risks associated with the country’s debt sustainability are creating an obvious and conspicuous pressure on arranging that financing at favorable rates. Therefore, it seems logical, however practically inefficient it may be, that the current government is trying its hands at every way to bring money into the economy, even if it means pardoning tax evaders and punishing tax payers in the process.

Last year, when the PTI was in the opposition and the Nawaz Sharif administration announced an amnesty scheme, now-Finance Minister Asad Umar called tax amnesty schemes “a slap on taxpayers’ face.” Now times have changed and there are rumors that the prime minister is contemplating a tax amnesty scheme to overcome the shortcomings of FBR’s tax collection and bring more money into the country. Researchers and economists are divided on the potential benefits that another amnesty scheme may have.

“At the time of the 2018 scheme, global conditions were favorable in the sense that it was becoming less and less secure to maintain assets abroad with impunity,” Sohaib Jamali, columnist and researcher at Business Recorder, told Profit. “In fact, I believe that this particular amnesty scheme could have fetched even more in declarations and tax collections had Imran Khan not been so loud and clear in his aims to bring the beneficiaries of such schemes to task.”

Speaking about the potential upcoming amnesty scheme, Jamali said that it will be of little to no benefit without addressing three concerns: an assurance against harassment of business community members, especially those who have already taken advantage of previous amnesty schemes; understanding that not all undeclared assets are a product of ill-gotten money; and a follow-up of the scheme with strict action against those who do not avail it. In his article published recently, he wrote: “Once that ball is set in motion, and the people are convinced that there is no way you can cheat the system anymore, that’s when the government should offer a new amnesty scheme as a one-time escape route. At present, the people know that the government doesn’t have the ability to bite; not even the teeth to show for.”

There are two things to note here. Firstly, in 2018, the Lahore High Court declared the 2013 amnesty scheme illegal, which cause severe damage to trust among the business community. The aftereffects of that scare can still be seen in the unwillingness of Pakistani citizens to declare their assets despite promises by the government that no legal action will be taken against those who avail such schemes. Secondly, there are no noticeable results of the hype around the empowerment of the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) after the 2016 and 2018 schemes to act against those who did not avail these amnesty schemes and were on NAB’s radar for possessing undocumented assets gotten through criminal activities. Put together, this means that so far these amnesty schemes have created terror in the hearts of those who wish to declare their assets but have done nothing to terrorize those who continue to operate outside the legal boundaries of maintaining wealth within Pakistan and abroad.

Economist and former caretaker finance minister Salman Shah agrees with the assertion that the current international environment could be one of the factors that works in favor of the latest amnesty scheme. But unlike other experts who spoke to Profit, he is rather hopeful that a well-crafted scheme might be exactly what Pakistan needs at this dire hour of enormous external debt and depleting national reserves. “However, we cannot continue to have amnesty schemes and then also maintain a draconian taxation system that is likely to keep discouraging people from entering into the legal tax fold or paying taxes,” he says.

Shah also said that despite being one of the signatories of The Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR) by the World Bank, Pakistan has not yet followed up on its international cooperation agreements to bring back stolen wealth and act against money launderers. “But there is a crackdown happening on unaccounted wealth all over the world and moving money and assets to Pakistan will be a better option under such circumstances,” he said.

Looking at the history of Pakistan’s amnesty schemes and the current prevalent international environment, it is safe to conclude that the government needs to at least conduct tax reforms and implement amnesty schemes together if not introduce reforms first and offer amnesty later. The beneficiaries of these schemes need to be given proper and reliable assurances that they will not be harassed and hunted after for availing the new scheme, and at the same time NAB and law enforcement agencies need to go with full force after those who do not avail the amnesty scheme. Without these measures taken simultaneously, there is little hope that a future amnesty scheme will help replenish Pakistan’s foreign reserves, improve the tax net, or create any positive change in FBR’s performance with respect to tax collection.