The year is 2019. Greta Thunberg is sailing the Atlantic to campaign for climate change. Young people around the world are marching for climate inaction, including in Pakistan. After all, this week, Karachi is scheduled to be swamped by incoming tsunamis, and, in any given week, Lahore suffers from hazardous levels of smog. The world as a whole is struggling to find new renewable energy resources, and moving away from non-renewable resources like coal.

And standing on the complete opposite end of this wave of change are the very serious men of Pakistan’s energy sector. Men like Ahsan Zafar Syed, who is the chief executive officer of Engro Energy Ltd, a position he has held since March 2019, though his association with Engro stretches back to 1991. Engro Energy comprises three separate subsidiaries, but really the main star is Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC), and Engro Powergen Thar Ltd (EPTL). Collectively, they are often known as just the ‘Thar coal project’, mainly because it is the very first one of its kind.

Ahsan has one guiding principle: that “this country deserves a cheap source of energy.“ He has absolutely no patience for critique of the coal project. And to that we say: fair. The Thar Power Project, purely by sheer size, is one of the most remarkable feats that any Pakistani company has achieved. This reporter visited Thar in late 2017, and was struck by the colossal scale of construction taking place in a district only 380 kilometres from Karachi, yet economically depressed and removed from the national economy.

If you ask Ahsan Syed, this is not a story about new energy or the climate: this is a story about how one corporation managed to pull of the feat, with no western financial backing, to start one of the only indigineous coal power plants that will add power to the national grid. In this narrative, Engro is an example of a responsible corporation, practically a national asset, and helping pave the way to solving Pakistan’s energy crisis – and if anyone is saying otherwise, well, they’re ill informed. Is it true?

The history of Thar Power Project

The Thar Power project was always a little up in the air. Speaking to Profit, Ahsan Syed says, “People had heard that there is coal in Thar, and there was a myth whether this coal can be used for power generation. Engro took a leap of faith and we invested so much time… it took us 9 years of hard work, effort, sweat and blood, to take this project to this stage.”

Engro Energy Ltd was formed in 2007, and initially focused on the Engro Powergen Qadirpur, a gas power plant. In 2009, it formed the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC). This mining company is a public private partnership, with seven partners: the major shareholder is the Government of Sindh, at 54% and Engro has around a 12% share. The other partners include Thal Ltd, Habib Bank Ltd, HUBCO and the China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC).

Its linked company, which manages the power plants, is Engro Powergen Thar Ltd (EPTL), formed in 2014. Engro has 50.1% ownership, with the remaining ownership belonging CMEC, Habib Bank, and Liberty Mills Ltd.

While the ownership structure of both companies differs, both companies are managed by and employ Engro employees.

Both of these companies operate in Thar Block II. To help explain what that means, Ahsan picked up a regular A4-sized magazine lying on his coffee table.

“So suppose this is Thar. This entire magazine, this is the Thar potential of 175 billion tonnes of coal. And this is about 55,000 square kilometres area. This potential is equivalent to Irani and Saudi Arabian oil put together. This potential is about 68 times more than the current available quantity of gas.”

He then places an iPhone on top of the magazine. “Only this area is currently being explored, and by explored I mean drilling. And the government of Sindh has taken this section [the iPhone] and has divided it into 12 blocks. And now a small piece of that, let’s say the Apple sign on the back of this phone, that one block, called Block II, has been given to Engro. This block is equivalent to only 1%, only 1% of Thar’s potential. It’s about 100 square kilometres.”

From there Ahsan elaborates: “When you start digging in that allocated area, you basically hit a pit that has 3.8 million tonnes of coal. And that is our first project, Thar Phase 1. And we have constructed a coal [fired power] plant next to it which is giving us about 660 megawatts (MW) of electricity. They are corresponding numbers”. Or more accurately, under Thar Phase 1, two power units of 330 MW were constructed.

For Ahsan, it is simple mathematics. While still speaking to Profit, he got up and pointed to his office’s fish pond. “Imagine this pond is that very coal pit. And imagine you keep expanding this pit. So basically, in multiple of 3.8 tonnes, as you keep expanding, you’ll keep putting up power plants of 660 MW.”

Coal can be roughly divided into four categories: anthracite, bituminous, sub-bituminous, and lignite. Most of the coal found in the Thar district is lignite, which is the lowest quality of coal and moisture -heavy. However, according to Ahsan, lignite coal can still be utilized – the only trick is to make sure that the power plants are close to the mine, as the coal cannot be transported across long distances well.

The reason why coal cannot be transported across long distances? If one uses trucks, it can often take more energy to transport the coal upcountry than one can get out of it by burning it. Using rail would be more efficient, but that requires hoping that Pakistan Railways has the capacity to build anything after 1952, which is howling for the moon at this point.

The cheapest way to transport energy from coal, therefore, is through electric wires: burn it at the mine mouth to convert it to electricity, and then transport that electricity via the national grid to the rest of the country.

The project reached its financial close in April 2016. Engro then selected China Machinery Engineering Corporation as the EPC for both the mine and power plant. As timing would have it, both companies were then included in the Early Harvest Project of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. Phase 1 was then completed three months ahead of schedule in July 2019, and within budget, a point of pride for Ahsan.

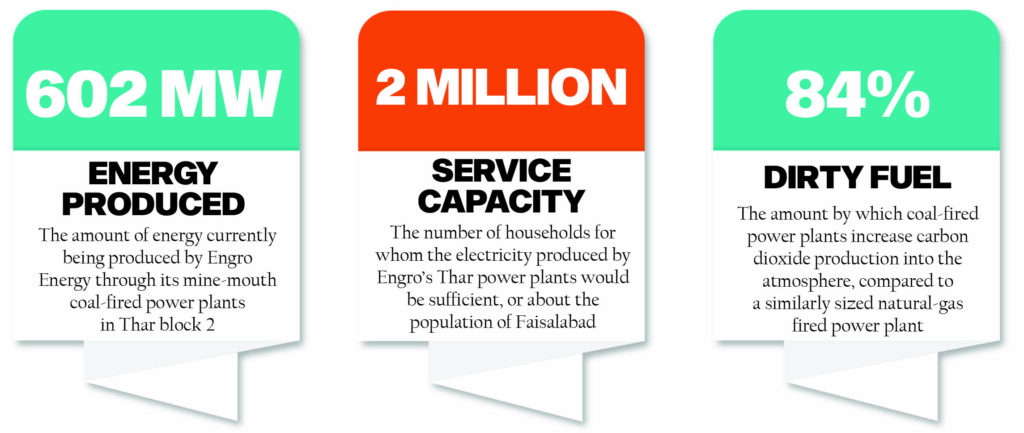

As he says: “The power plant that we’ve installed is the first indigenous coal-fired power plant in Pakistan. These two projects will provide energy security to the country. Right now, we are injecting 602 MW into the grid, which is equivalent to supplying electricity to 2 million households. And on a yearly basis we will be saving $150 million in foreign exchange.”

The trouble with financing

It’s a given that Ahsan, and by extension Engro, is extremely proud of the work they have accomplished. But Ahsan also views the project in terms of a nationlistic project: “We were carrying the burden of hope, of 220 million people of this country. A big burden of hope was on our shoulders, the shoulders of Engro, to move forward. Everyone was praying that, God, I hope they actually find coal.”

“When we talk about this country, whenever we take a nationalistic approach, it is a long-term approach. Indigenous coal is a long-term approach.”

One of the major roadblocks to the completion of Thar was financing. The nearly $2 billion project would not have been possible without the help of China. “You have to imagine the risk we took, no one was giving us money, no one was supporting us. And our country is a poor country. We did not have the money available with the government to do this project.” As he puts it a little more bluntly: “Hum say yeh project itnay paapar bailnay kay baad 10 saal mein huwa.”

It’s understandable that the government of Pakistan did not have the resources; but why did Engro only receive a loan from China, and nowhere else?

The problem? Coal. And this goes back to the earlier point about dirty energy: not one western financial institution was willing to finance a coal project in Pakistan.

Ahsan himself rightly points out: “Right now there is talk about sustainability, about the environment. So everyone said, why are you putting this coal project up? You should be putting wind energy, solar energy. Why are you ruining the environment? We won’t give you a loan.”

Why indeed is Pakistan investing so heavily in a nonrenewable resource? For one there’s the expected energy potential of Thar, which makes both companies and the Pakistani government look the other way. For another, Ahsan himself sees no problem with the construction of coal power plants.

First, he uses other developing and developed countries as an example Pakistan can follow: “This is a misnomer. Right now as we speak, around 20+ countries, are putting up coal power plants. Huge power plants are being put in Japan, in China, in India, and in South Africa.”

Second, coal power plants around the world are being shut, Ahsan insists it is because of inefficiency: “We need to ask ourselves, the right question. Those plants are closing that have outlived their useful life. If someone asks me coal plants are closing, I’ll say yes, they’re shutting. Which plants? Those that have outlived their useful life, those that are inefficient, and those that are base load plants.”

In his defense of the EPTL, he says: “I have a third-generation coal power plant. My emissions from my power plant are well within World Bank guidelines.”

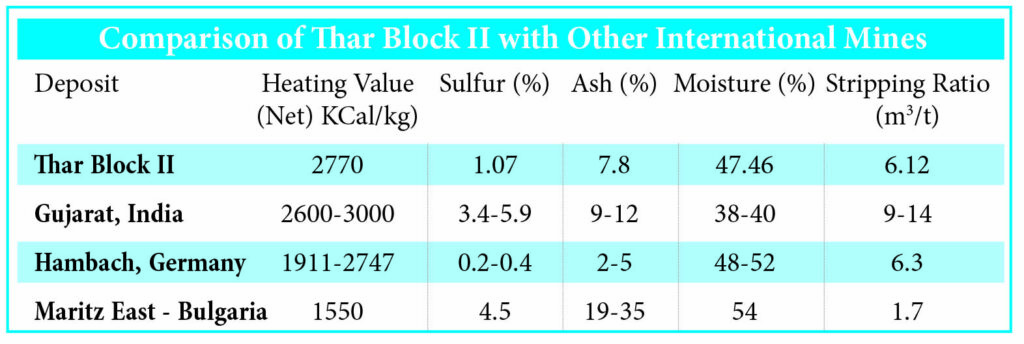

In a clarification statement published in 2018, SECMC maintains that the lignite reserves found in Pakistan are of a much higher quality than coal reserves in India, Germany and Bulgaria. The statement points to Thar coal’s low sulfur content and low ash generated post combustion as evidence, among other metrics.

That may well be so, but here is another statistic that is important to remember: Coal (the lignite variety most commonly used in Pakistan) emits 33.5% more carbon dioxide than oil-fired power plants, and 84% more than natural gas, according to data from the United States Energy Information Administration (EIA). There is no denying the fact that, no matter how efficient a coal-fired power plant, a natural gas plant will always be the cleaner option.

Shamsuddin’s squabble with Sindh

Throughout the conversation, Ahsan is quick to emphasize the support provided by the government of Sindh. As he says “There were no roads when we went to Thar. There was no source of water. There was no airport. There was no tariff regime, or how a tariff is to be built for this overall project. So the government of Sindh helped us, infrastructure was built, roads were constructed, the water line was laid.”

There is very acute reason for this. Ahsan’s predecessor was a man called Shamsuddin Shaikh, who had worked at Engro from 1987, and had been the CEO of SECMC since 2010. His retirement was due in 2023, but he dramatically resigned in November 2018.

The reason? He claimed that the Sindh government had failed to provide basic amenities promised to Tharis, and had also failed to provide electricity to Tharis, calling the government utterly “indifferent”, and accusing them of “hollow promises and fake slogans”.

Obviously, as Engro’s new CEO, Ahsan could only add: “Shams’s opinions are his own, those are his personal views, and I cannot comment on them. You need to understand that Engro is an institution. Shamsuddin Shaikh worked very hard on this project and he contributed a lot on this project, and he took this project ahead. But Engro is an institution, and a company like Engro, people change.”

Still, it’s clear that whether under Shamsuddin, or under Ahsan, Engro has heavily promoted its corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaign. Whether the Sindh government is actually incompetent is anyone’s guess. [Editor’s Note: The author’s snark is much appreciated, but we would like our readers to know that, unlike Engro management, we at Profit have absolutely no qualms about calling the Sindh government incompetent.] But that very CSR campaign has come under scrutiny, as we explain below.

Enough about coal: what about Tharis?

For someone who talked at length about coal, Ahsan is very clear about his definition of success for the Thar power project.

“For us the definition of success is not that the people living in Karachi who are using two air conditioners, and we provide them a third air conditioner”, he says. “For us the definition of success is to make the people of Thar self-reliant. The coal has come out of the land where they are living. They deserve to get the maximum benefit.”

This is a bold statement from a company that has been responsible for the displacement of hundreds of Tharis for the construction of the mine. But Ahsan frames it as: “We have converted the affectees of Thar, to the beneficiaries of Thar. If we are mining coal from under their land, and we have relocated them, then they are no longer affected, they are the beneficiaries.” He informs that Engro has built free houses for at least 171 families that will be displaced.

Engro’s main relationship with the Tharis is in term of employment. According to Ahsan, the mine itself had at one point up to 70% of local Tharis employed. Meanwhile, the power plant has up to 50% of local Tharis employed. Engro spent months on training programs for Tharis to work in the mine and the plant. The company also started a Female Dump Truck Driver Program, which has trained at least 60 candidates from Thar to drive.

Engro also manages the Thar Foundation, which is in charge of ‘social impact’ in Thar. In health, Engro has helped build: a 125-bed hospital in Islamkot, Marvi Mother and Child Health Clinic, and Cataract Eye Camps. In education, Engro has spearheaded, 24 schools with 2,500 children studying there, and helped update the Government Polytechnic Institute Mithi, which caters to 180 students.

And yet: since the very start of the SECMC project, there have been cries from Thari and Sindhi activists that Engro is responsible for taking away the agency of Tharis, and is modelling a top-down approach towards development. There is also the charge that Engro uses performative and palatable ‘women-empowerment’ activities, like the 60 dump truck drivers, to mask its real agenda: i.e. destroying Thar land.

Then there is the charge that Engro’s mining activities have altered the water table in the surrounding villages, forever changing the ecology of the area. Between 2016 and 2018, Thari families held a strike for 635 days outside the Islamkot Press Club, precisely about issues like these.

On the issue of water, Ahsan has a clear stance: “We have 36 wells that monitor the water level on a monthly basis… they also measure toxicity. When they said that the water level is decreasing, that there are toxins, we put 36 wells and retrieved the data, and provided a record to them.”

But as for other criticism lobbed by Tharis? Ahsan says its difficult to keep everyone happy: “If you hire people from one village, the other village complains. If you hire from that village, the first village complains. If you hire a villager who’s affiliated with a certain political party, then the other political party worker complains. We try and hire everyone on a merit basis.”

As per Ahsan, Engro’s ‘inclusive’ CSR model has been so successful that Tharis employed in Block I (managed by Shanghai Electric), are badgering their employers to provide them with the same level of amenities that Engro provided in Block II.

It is interesting to note that the CSR that Ahsan mentions are the kind of systems that should really fall under the Sindh government’s responsibility. Sure, it is Engro’s job to hire people, but it is the SIndh government’s job to provide basic amenities, that at this point Engro is providing. And that is concerning – if Engro, or in the future Shanghai Electric, are basically quasi-states operating in a place that has had historically zero investment, what does that say about the future of Thar?

The future of Thar Coal

Moving forward, Engro Energy has many plans. First, the financial close of Phase 2 of Thar project is expected to happen in December. This phase includes the construction of two more power plants of 330 MW each. Phase 3 will then include the expansion of Block II.

Another potential project is the construction of a railway line from Thar to the national railway. This is intended to help distribute Thar coal to the rest of the country, and helps eliminate the need to have a power plant at the mouth of the mine. The phases are expected to continue until 2024.

It is unclear how much of a market Thar coal will have in the rest of the country, however. Many power projects have already been set up to use liquefied natural gas (LNG), for instance, imported mainly from Qatar. LNG is both cheap and relatively easy to transport across the country, and has the benefit of an existing nationwide network of natural gas pipelines through which it can be pumped.

Not that Engro is likely to complain: Engro Elengy, another subsidiary of the parent Engro Corporation, is already supplying much of the natural gas being used by gas-fired power plants throughout much of the country.

Still, the folks at Engro Energy believe that ‘indigenous’ coal is better than imported natural gas, and view the Thar coal project as a national asset.

Ahsan Zafar Syed is expected to be at the helm of this project. He is genuinely banking on Thar coal power project to help propel Pakistan into a new energy phase. As he says: “I really want my country to leapfrog in all the energy areas.” Never mind that we’re leapfrogging using coal.

You wrote all that and didn’t tell us how much the electricity generated by these power plants costs. The rest of the world media tells us that solar is now cheaper than fossil fuel. So can we please have some numbers?

Comments are closed.