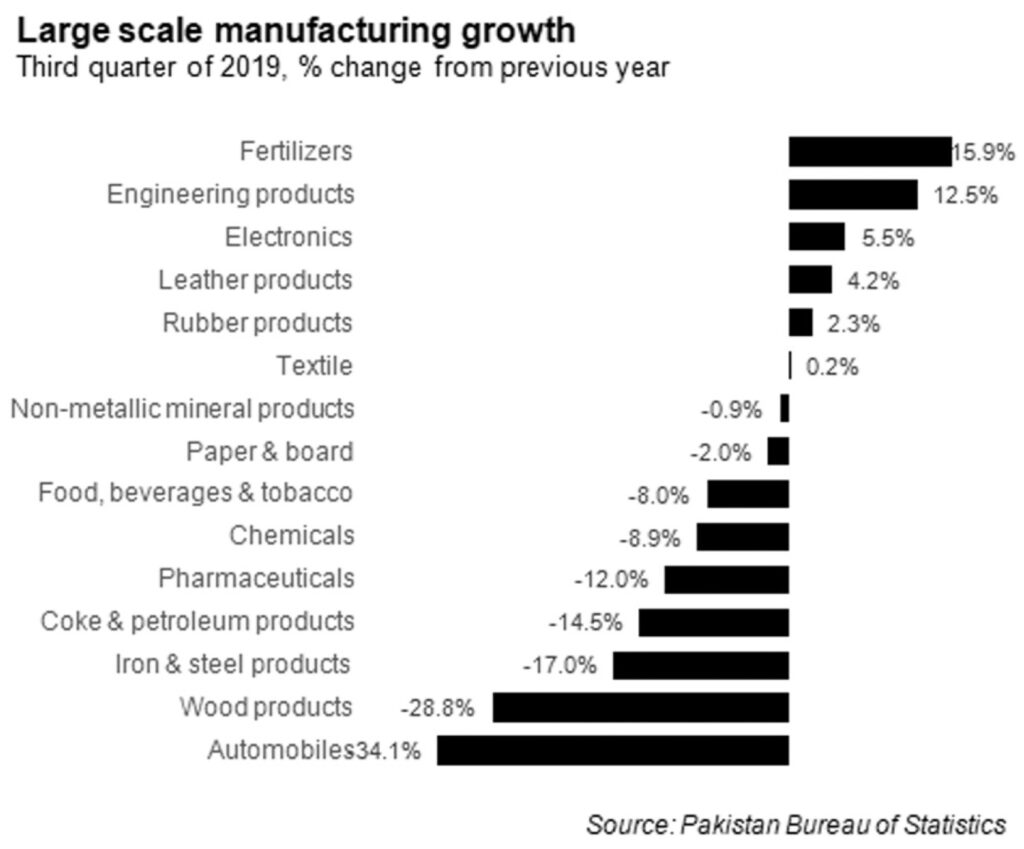

It comes as no surprise to any observer of the Pakistani economy that large-scale manufacturing continues to decline in output. For the third quarter of 2019, the LSM index declined by 5.9% compared to the same period last year, according to data released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

The variation by industry, however, revealed some interesting patterns, and suggest that there may be some positive macroeconomic news on the horizon for the coming year, particularly as it relates to exports.

“A breakdown of the broader numbers revels that while the overall performance remained broadly disappointing, some improvement was seen in export oriented sectors such as textiles and leather products (growing 0.17% and 4.24% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2019),” wrote analysts at JS Global Capital, an investment bank, in a research note issued to clients on November 26.

Yet the industry that saw the most rapid recovery from an abysmal last year was the fertiliser manufacturing sector, which saw production rise by 15.9% during the third quarter of 2019 compared to the same period last year. An increase in fertiliser production and sales reveals the following facts: farmers have purchasing power again and are able to invest in growing their production of crops.

Pakistan’s agriculture sector has had a rough few years, including an especially rough fiscal 2019. For the past 10 years, the agriculture sector has grown at a pace slower than the broader economy, and in 2019, the sector grew by just 0.85% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Given the fact that the rural population growth rate is currently higher than 2%, that means that the average farmer was worse off in 2019 than they were in the previous year.

Yet rising purchases of domestically produced fertilisers by farmers is a bullish sign for agriculture. Given the fact that these purchases took place between July and September of this year, ahead of the October–December “Rabi” planting season, suggest that the Rabi harvest in April and May of 2020 is likely to be a good one compared to last year.

In terms of crop value, though, Rabi is the less lucrative of the two planting seasons in Pakistan. The only major crop grown in the Rabi season is wheat, with the remaining crops most commonly grown during the season being gram, lentil (masoor), tobacco, rapseed, barley and mustard.

Nonetheless, a successful wheat crop would be important to the country’s food security and economic growth. In the 2019 harvest, Pakistan’s wheat production clocked in at 25.2 million tons, about 6.5% lower than the 26.7 million tons the country was able to grow in 2017.

And a successful Rabi season would set up farmers well to invest in production of the all-important Kharif season, for which planting happens between April and June. The other three of Pakistan’s four main crops – cotton, rice, and sugarcane – are all grown in the Kharif season.

The overall patterns of the industrial sector, however, appear to indicate that the central bank’s policies of weakening the rupee to improve the country’s balance of payments and increase exports is working.

“We would like to highlight that the quarterly performance has been in line with the State Bank’s stance that inward-oriented sectors continue to face headwinds while activity in import-competing and export-oriented sectors has picked up,” wrote analysts at JS Global Capital.

Yet even as some export-oriented sectors continued to improve, the fact that a massive decrease in the value of the rupee has not caused a more significant increase in the value of Pakistan’s textile exports suggests that the industry is simply less competitive than its global rivals in a manner than have little to do with the government’s macroeconomic policies, the wailing of the crybabies at the All-Pakistan Textile Mills Associations (APTMA) notwithstanding.

Among the other sectors that continue to do well include the engineering sector, which continues to benefit from the expansion in power generation capacity, even as the rest of the economy continues to remain sluggish. Other beneficiaries include the electronics sector, which may be a leading indicator in a recovery of consumer purchasing power.

The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) – led by Governor Reza Baqir – appears to be following a relatively strict macroeconomic correction policy, in conjunction with the prescription of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Over the five years of the third Nawaz Administration, Pakistan had an unjustifiably strong exchange rate, kept there by the government expending foreign exchange reserves, raised through expensive bond offerings on the global market. In addition to costing the government money that it did not have, that artificially inflated exchange rate effectively subsidised imported consumption and punished exports, causing the trade balance to become even worse.

Since the change of administration following the 2018 elections, the government has been in course-correction mode, particularly on the external front, seeking to improve the current account balance and stabilise the exchange rate at a much lower rate than two years ago.

That stabilisation exercise, however, does not come without pain, as economic growth slows down in response to higher inflation and interest rates that result from the sharply higher price of imported goods. The industrial sector of the economy is particularly vulnerable to that slowdown, since is most reliant on imported inputs as well as borrowing costs.

“Going forward, we believe that while overall LSM performance could remain subdued in the immediate term, it is likely to improve once the stabilization measures start to bear fruit,” wrote the analysts at JS Global Capital.