On March 10, a five-member bench of the Lahore High Court issued a 103 page judgement on the issue of mortgaged property, a decision that has the potential to fundamentally transform the mortgage market in Pakistan, though the decision is not without controversy.

In summary, the court decided that a 2016 provision in banking laws – which allows banks to auction the mortgaged property of loan defaulters without obtaining a court order first – is constitutional.

How did the court decide on this? Why was the law promulgated in the first place, and why was it challenged? What does this mean for mortgage borrowers going forward? And what will this mean for the country’s housing market and mortgage finance industry more broadly?

The answer to all of these questions lies in understanding a single section of a law that was originally promulgated almost two decades ago: Section 15 of the 2001 Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance.

Profit breaks down the judgement reading, and spoke to both petitioners and defendants about the case to learn more. And we add the economic context surrounding the decision to help understand what impact it is likely to have on the country’s housing and financial sectors.

What is Section 15?

The 2001 Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance came into force in the early years of the Musharraf Administration, when then-Finance Minister Shaukat Aziz was seeking to update Pakistan’s regulatory structure to make credit markets in the country function better. It was intended to replace the 1997 Banking Companies (Recovery of Loans, Advances, Credits and Finances) Act.

At its heart, the law was designed to address a fundamental problem that drives at the core of banking: how to enforce a loan contract against a borrower who has defaulted on their loan payment obligations, and how to do so cheaply, and efficiently?

In designing such a law, there are two sets of interests that need to be considered: those of the borrower, and those of the lender. Make matters too easy for the lender, and you open up the possibility of the lender engaging in highly exploitative behaviour with the borrower, and with a reduction in the demand for loans over time. Go in the opposite direction, however, and lenders would not be willing to lend to otherwise qualified borrowers, reducing the optimal level of lending and economic activity in the country.

Prior to the 2001 Ordinance, the law appeared to be biased in favour of borrowers, forcing banks to go through the full court case before they could recover the property from the loan defaulter, a process that took several years and cost millions of rupees for each individual loan.

The 2001 Ordinance – promulgated as it was under a banker finance minister – was designed to make it easier for banks to take control of and sell property of loan defaulters without having to wait for a court order to do so. This would significantly reduce the banks’ risks, and thereby make it easier for them to lend to consumers.

The 2001 law has 29 sections, of which Section 15 allows banks to sell mortgaged property, in the case of a default in payment by the customer. ‘Mortgaged property’ in this case refers to any immovable property mortgaged to a financial institution, like a bank.

This section was in place until December 10, 2013, when the Supreme Court of Pakistan declared Section 15 of the 2001 Ordinance as ultra vires, or an act that is beyond one’s legal authority, to the constitution of Pakistan. Section 15, it was stated, did not have adequate protections for borrowers, nor did it provide borrowers with adequate remedies during the process of enforcement of a mortgage.

Following the Supreme Court’s judgement, the State Bank of Pakistan scrambled to fix the Ordinance. It started a process to reframe the amendments in light of the judgement, and also in light of the banks’ needs to be able to continue lending while reducing their risks. The result was the Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) (Amendment) Bill, drafted in 2015.

This bill made amendments to eight different sections of the Ordinance, but made the most substantial changes to Section 15, adding three subsections, and significantly changing the language of at least two subsections. The Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Amendment Act passed both houses of Parliament and was signed into law in August 2016.

Almost immediately, there was an outcry. A Lahore High Court bench suspended enforcement of the newly reconstituted Section 15 of the law while the matter was under litigation at the court.

The matter languished in court right up until November 2019, when arguments for both sides were heard, this time in front of a five-member bench, led by Lahore High Court Chief Justice Mamoon Rashid Sheikh.

The case against Section 15

The petitioners – Muhammad Shoaib Arshad and others – argued that Section 15 would give banks arbitrary powers to sell mortgaged property without seeking “adjudication of claims through judicial process”, and that such a process goes against Article 10-A of the constitution, which is the right to fair trial.

The petitioners argued that borrowers and banks already had their relationship and dispute resolution mechanism defined under Section 9 of the Ordinance, which identifies the Banking Courts as the venue for adjudicating defaults: “Where a customer or a financial institution commits a default in fulfillment of any obligation with regard to any finance, the financial institution or, as the case may be, the customer, may institute a suit in the Banking Court”.

Since Section 9 already exists, in effect, the petitioners argue that the rewritten Section 15 gave too many powers to banks to start proceedings against loan defaulters. As they put it, “the initiation of the recovery process before the determination of default of the customer, is like putting a cart before the horse”.

In particular, the petitioners were concerned about the potential misuse of Section 15. For instance, they argue, bank managers could invoke the section against borrowers who have a mortgage against ‘coveted’ assets, presumably a reference to particularly desirable real estate assets.

According to the petitioners, “The unfettered and unstructured discretion extended to financial institutions, without predetermined criterion, would result in exploitation of [borrowers] and expropriation of properties… there is no safeguard available against demands of exaggerated and unrealistic claims, unilateral determination of defaults and hasty, collusive, and pre-arranged sales.”

As for who gets to value the mortgaged property, the petitioners argued that banks would appoint evaluators at their own discretion, leading to the possibility of collusion and exploitative behaviour by the banks. They called this method of auction “prejudicial, mere eye-wash and classic instance of conflict of interest”.

The petitioners argued that the reintroduction of Section 15 via legislation was unconstitutional, because it went against Article 189 of the constitution, which says that decisions of the Supreme Court are binding on other courts.

The case for Section 15

The petitioners are a group of lawyers who have – in the past – acted as litigators on behalf of companies that have defaulted on their loans. On the defence is the Finance Ministry, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), and the banking industry.

While the petitioners were concerned about the banks’ overreach, the defendants, led by the government, were concerned about the rise of non-performing loans in Pakistan, and the relative ease at which people seemed to not pay back banks. According to the government, Section 15 was reenacted precisely to curb this ‘menace’ that was having a significant effect on the economy.

And to defend their position, the government pointed to the macroeconomic benefits of the rewritten section of the law: “The growth in the volume of bad debts had resulted in a liquidity crunch, where the profitability of the banks has come down, which has dissuaded them from offering new loans… default in the payment of loans constitute squandering of public funds, as the banks used depositor’s money for extending finances.”

The government also argued against the notion that Section 15 was infringing on fundamental rights granted to people under the constitution. According to them, the reintroduced section has two new subsections to protect mortgagors.

Under Subsection 13, a banking court could grant an injunction to restrain the sale of a property, under certain conditions. Under Subsection 14, a borrower could ask the banking court to void the sale of the property on the grounds of fraud.

In addition to this, borrowers were also protected by the The Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Rules, 2018, which lays out even more rules on how loan defaulters’ properties are to be sold. For instance, the bank must have loan defaults and amounts verified by a chartered accounting firm, the cost of which will be paid for by the bank.

The government argued that this combination of subsections and rules were enough to “discourage predatory tendencies and vested interests of [individual] bankers”.

What did the court decide?

In the end, the decision was not close. Four of the five judges agreed with the defendants: the federal government, the State Bank, and the banking industry. The majority opinion, written by Justice Asim Hafeez, addressed the three major issues brought up by the petitioners.

The first was the ‘due process’ argument made by the petitioners: that the law as it currently stands does not have enough protections for the borrower.

On that matter, the court acknowledged that the original Section 15 did not have adequate protections for borrowers, and went so far as to say that it was “insufficient and feeble to counter a blitzkrieg by the financial institutions.”

But the court agreed with the defence that the new Section 15 had explicit and conspicuous remedies, in particular, Subsections 13, 14, and 15. And it did so despite setting for itself a relatively high standard to meet with respect to what would constitute adequate protections for borrowers: Did the remedies in the rewritten Section 15 provide enough rights to the borrower, “both prior to the conduct of sale and, in particular, after the fall of the hammer?”, the court asked. The court found that, in both cases, it had.

Under Subsection 13, the borrower could object to the creation of the mortgage liability and amount of the outstanding loan claimed in a banking court. The borrower could also exercise the right of redemption of property, subject to the payment of the outstanding loan amount.

The court also noted Subsection 12, where banking courts are given exclusive rights to judge on disputes.

In summary, “Section 15 has not affected, prejudiced or taken away the right of the [borrower]”.

In fact, the court said that Section 15 gave two rights to the borrower: the right of redemption of mortgaged property, and also the right to object to the conduct of sale – this is all after “the fall of the hammer”.

The second major argument by the petitioners was an ‘equal protection’ argument: that Section 15 would allow banks to discriminate against borrowers and treat them unfairly. On this, the court needed to define a borrower, and whether the equal protection clauses of the constitution would be relevant in this matter, and if so, whether Section 15 violated those constitutional provisions.

On this matter, the court ruled that the law did not violate the equal protection provisions. The constitution prohibits discrimination between citizens, but it does not prevent them from freely engaging in commercial contracts with each other that would then bind them to act in one manner or another.

A borrower is one who has signed a legally binding and valid agreement, and secured payment of the money against specified immovable property. The borrower makes contractual promises and commitment with the lender (the bank).

Section 15, therefore, was only enacting action against a specific class of people, i.e. borrowers, and more specifically, loan defaulters. And that very action, the court ruled, “cannot be declared unconstitutional on mere apprehension or allegation of discriminatory dispensation.”

In short, the borrower signed up for this, and cannot declare the commitment discriminatory against him.

The third issue was one of the court’s standing: could the Lahore High Court even rule on the matter, given the fact that the Supreme Court had previously ruled on the older draft of the law and had ruled it unconstitutional (the initial 2013 judgement).

On that matter, the Lahore High Court was categorical about the separation of the judiciary and Parliament.

“It is evident that the Court is not at liberty to inquire into the motives or mala fide intent on the part of the Legislature. Once a statute is competently made, the Court is not entitled to question the wisdom or fairness of the Legislature. Nor can the Court refuse to enforce a law competently made on the ground that the result would be to nullify its own judgment.”

Well, that was easily taken care of.

So did the court have a problem with anything after all?

Actually, yes. The court said that the Rules of 2018 were acceptable; in fact, section 25 of the 2001 Ordinance gives the federal government the ability to make rules. However, the court had serious reservations with Rule-3 (c) (iv) of the 2018 Rules, which allowed an auction sale to take place even if there was only one bidder.

The concept of just one bidder does not sound very public. As the court noted, both Section 15 and the Rules referred to a “public auction”. This particular rule went against Article 24 of the constitution, which protects property rights, and is contrary to the spirit of competitive bidding.

Ok, enough legalese; what does this mean?

According to Shafaq Rehman, a Karachi-based corporate lawyer and partner at RIAA Barker Gillette, a law firm, the judgement affirmed what the legislature has already enacted: that it is a bank’s right to enforce a duly created mortgage.

Speaking to Profit, Rehman said that the judgment helps clarify the difference between a customer who has simply borrowed funds from a bank, and a customer who has mortgaged property with the bank.

“A customer is just someone who goes to the bank for financing. But Section 15 is dealing with someone who has not only borrowed money, but in addition, has provided security by creating a mortgage on immovable property in favour of a financial institution i.e. the customer has given an express right to a financial institution to sell immovable property mortgaged with the bank if the customer fails to pay,” she said.

If the mortgage has been created with the consent and knowledge of the customer, then the customer may not pull back from the commitment it has made to the lender.

The problem with the initial Section 15, was that the borrower was not kept adequately in the loop, and neither was the borrower provided adequate remedies during the process of enforcement of a mortgage. According to this judgment, the new Section 15 takes into account those deficiencies that the original Supreme Court Judgement noted.

According to Rehman, this latest judgement should not affect borrowers. “If anything, it should make them more aware of their rights and obligations towards financial institutions.”

Profit also spoke to the lead defence counsel in the case, Salman Akram Raja, the Cambridge and Harvard-educated litigator famous for his arguments on constitutional matters before the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

“It is important to note that this is really the norm around the world – in the US, India. Many jurisdictions have provisions similar to Section 15.” said Raja.

According to Raja, the court system in Pakistan is a long and laborious process, in which cases would often be heard eight to ten years later. Delayed cases of defaulting borrowers often mean a higher chance of a favorable settlement goes up.

“It’s really about the delay in the judicial system in actually settling the matter.” said Raja. “The key motivation behind this was that the bank should feel more confident and have the security that they will be able to enforce this fairly and efficiently, and not have to go to the court system.”

According to Raja, the borrower had been disproportionately powerful for far too long. This judgement served to strike a balance between the borrower and the lender.

Why the case moved so fast

It is a bit odd that this obscure section regarding mortgaged properties that had been languishing about since 2016 suddenly got a new lease of life in 2019.

You can thank Naya Pakistan for that. Prime Minister Imran Khan had introduced the Naya Pakistan Housing Programme in July 2019, which has as its goal to build 5 million new housing units in Pakistan over the next five years.

The only problem was that the Asian Development Bank (ADB) was unwilling to give loans for this project without some kind of reassurance with regard to Pakistani law. After all, those 5 million homes need to be sold to people, and most of the buyers will need loans to buy those homes, which in turn means that banks need to be willing to lend to those new borrowers. Banks, however, would not be willing to lend without knowing that, if the borrower defaults, they will be able to recover the money by selling the house.

The Prime Minister had appealed to the Lahore High Court Chief Justice, who had fixed the date of the first hearing for September 13. Later, Chief Justice Sardar Muhammad Shamim Khan fixed the date of subsequent hearings before a larger bench in November 2019.

This was confirmed by Raja, who said that the ADB, and even the World Bank, had been waiting to give money to the housing sector, but were waiting on a concrete decision by our courts.

Profit also spoke to one of the petitioners, senior lawyer Shahid Ikram Siddiqui, the sole partner at a Lahore-based law firm Lawyers and Lawyers International, which in the past has probably represented more loan defaulters than any other law firm in Punjab. From his perspective, this entire judgement was passed in order to accommodate the government in getting a loan from the ADB.

“This is a completely political judgement,” he said.

Will this be appealed in the Supreme Court?

The short answer is: yes. Any decision taken by the Lahore High Court, can be appealed in the Supreme Court of Pakistan. No decision taken by a high court is binding, as it is by the Supreme Court. An appeal really just depends on whether the individuals and petitioners in question have deep enough pockets to keep going forward.

According to Siddiqui, an appeal is expected to be drafted this very week. For him, it was not even a question that the appeal would not happen. “This case had a very weak judgement, where they just changed the language of the section, but the intention [of the bank] still remains.” he said.

He also claimed: “Out of the five judges, the most junior judge wrote this judgement. Asim Hafeez only became a judge a year ago, and the chief justice did not write this judgement. It has so many weak points.”

It is unclear if the implementation of the Lahore High Court judgement will be stayed – that will depend on appeal filed. But it is a fight that Raja is prepared for. “We completely expect this decision to be appealed,” he said. “Who knows how long this will go on for? It’ll be a couple of years before it’s finally resolved.”

[…] کے قیدیوں کے لئے خوشخبر ی لاہور ہائی کورٹ نے صوبے بھر کے قیدیوں کو فورارہا کر نے کا حکم دے دیا۔ اس […]

The decision of the High court is against the law and the constitution and also against the rights of the borrower’s. The actual solution lies in the constitution of more courts and the improvement of the auction procedures through empowerment and facilitation of the banking courts and the judges and settings up the prosecution department for the banking courts which is non existent at present. Similarly, the number of courts and the appellate courts is also highly needed. Laws relating to the auction need to be improved to enable the courts make and enforce their judgements more promptly and effectively..

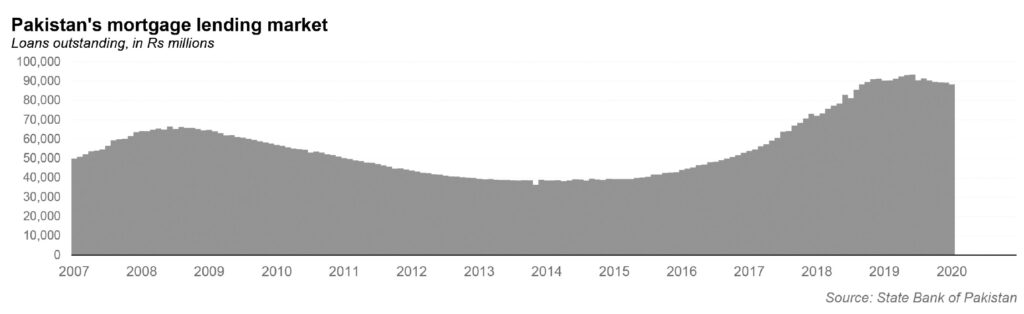

[…] of the problem of why mortgages have failed to pick up in the country. You can read the full detail here, but it all started in 2001 when the then banker Finance Minister Shaukat Aziz, got the 2001 […]

[…] of the problem of why mortgages have failed to pick up in the country. You can read the full detail here, but it all started in 2001 when the then banker Finance Minister Shaukat Aziz, got the 2001 […]

[…] it is hard for banks to take control of and sell properties. You can read the full detail here, but main point is that the lawmakers are trying to change this given the need to make Naya […]

Comments are closed.