Every night, an estimated 20 million Pakistanis go to sleep without a roof over their head. That is a whole 9pc of our population (consisting largely of nomadic tribes that herd goats and sheep). Want another depressing figure? (warning: there is no shortage of these in this article) Around 50% of Pakistan’s urban population – that is roughly 39 million people – live in a slum, or a katchi abadi.

To live in a house in this country is a blessing. To have enough on-hand money to buy a new house is a luxury. To walk into a bank and ask for a housing loan – now that is near impossible.

It is in this bleak scenario that the Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company (PMRC) exists. The company formally commenced business in 2018, and it shows. On its slick, brand new website, PMRC proudly proclaims, against colourful backdrops of various cities of Pakistan: “Housing for all Pakistanis”.

All, you say? Yes, all, said its chief executive officer Mudassir Khan in conversation with Profit. The cautiously ambitious but definitely optimistic (who can blame him) former banker is the head of a tiny company, consisting of just 27 staff members. And yet its bold aim is to reshape the entire narrative of homeownership in Pakistan. Its mission: “To be a leading catalyst for the development of housing finance and capital markets in Pakistan.”

It is impossible to understand what PMRC is trying to achieve, or what it is even up against, without first understanding the state of affordable housing finance in Pakistan, or more accurately, the lack thereof. How did Pakistan’s mortgage industry lose the plot so fast? How has the government been so blank on this topic?

Pakistan’s housing problem

By several estimates, Pakistan is facing a shortage of anywhere between 10 to 12 million housing units. The housing shortage for urban areas is estimated to be around 4 million units. And every year, according to the State Bank of Pakistan, 700,000 units are added to the overall deficit. Only about half of this demand is ever actually met.

Most of the housing backlog falls on the back of low and lower-middle income segments of the population. According to a Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) policy brief “Urbanization in Pakistan: the availability of housing”, if one looked at the housing shortage by income bracket, those those whose annual income was between Rs12,000 and Rs50,000 faced a housing shortage of 2.6 million units; those whose annual income is between Rs6,000 and Rs12,000 face a housing shortage of 3 million units, and those whose annual income is less than Rs6,000 face a housing shortage of 1.5 million units.

How did it get to this point? Several reasons. First, Pakistan’s urban population exploded over the last few decades, due to rapid population growth and rural-urban migration. It stood at just 22% in 1960 but has reached around 37% today, and is expected to cross 50% in 2050, according to the government. So housing demand has far outstripped housing supply.

Secondly, there is a shortage of land – well, kind of. The government owns around 40% of all the land in Pakistan, and acquiring that land can be a difficult process. The amount of land that is actually leased out to the private sector does not cater to low income groups – the very groups that need housing the most.

Land cost itself also contributes to the total housing cost. “The current land administration system is inefficient because development agencies buy finite urban land from government agencies, develop it, and then sell to consumers; however, government agencies auction off land leading to high prices and speculation,” explains the LUMS brief.

And lest one think that this is classic government inefficiency, the private sector is not exactly the most efficient either. Again, perhaps to cater to higher income groups, most housing development is in actual individual houses, rather than the construction of high rise or apartment buildings. As an example, Karachi is perhaps the only city in Pakistan that something actually akin to a skyline – and yet, one 2010 study showed that only 5% of urban land was used for apartment buildings, while 55% was used for individual houses.

Did the government notice the problem? No.

If one visits the Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme website, announced with much fanfare in July 2019 (more on that later), the PTI government has in clear letters spelt out:

“Housing sector has largely been neglected by various Governments in Pakistan. If at all it got any attention of the political leadership, it never moved beyond mere political slogans. Even if some work was done at the government level, it did not move beyond some desire and discussions, and not even put on any drawing table.” Political finger-pointing aside, this is actually a valid point. Affordable housing has been criminally neglected in both federal and provincial policymaking.

The first stab at improving this housing scenario was taken in 1978, with the Katchi Abadi Improvement and Regularization Programme, or KAIRP. This aimed to give leases and infrastructure to katchi abadi residents.

Then, in 2001 came the ‘National Policy on Katchi Abadis, Urban Renewal and Slum Upgradation’, to build further on the 1978 policy. Why, you may ask, have you never heard of these policies? That is because the policies apply to katchi abadis only established before 1985. This is outdated to the point of being laughable.

The slogan Roti Kapra Makaan may have been around since the late 1960s, but the National Housing Policy was only created in 2001. It aimed to create affordable housing for middle and low income groups, and also to regularise katchi abadis. Needless to say, this did not happen.

Then, there was the federal scheme of 2013, Apna Ghar, which was to provide 500,000 low cost housing units across Pakistan. The project never got off the ground and was shelved in 2017.

Provincial governments have fared only a little better. For instance, the Sindh government started the Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Town Scheme for around 27,000 plots, and the Punjab government started the Ashiana Housing Scheme in 2010 (though that one was mired in corruption controversies). The Sindh Katchi Abadi Act was passed in 1987, regularising around 600 katchi abadis, while the Punjab Katchi Abadi Act of 1992 regularised around 300 katchi abadis.

This is, of course, when the katchi abadis are not being demolished by an overzealous Supreme Court, though that is another story.

Perhaps the biggest indication of whether housing is a priority for the government, is that there was no official definition of what constitutes low-income housing until March 2019.

Housing finance in Pakistan

So there is a housing shortage, and the government seems unable or unwilling to provide help. Well, what about the private sector?

The State Bank, in its policy recommendations of 2019, was categorical about the private sector’s failure: “The formal financial sector has been failing to provide adequate and affordable housing finance to a large segment of the population.” Housing finance was only 1.7% of total private sector credit in 2018.

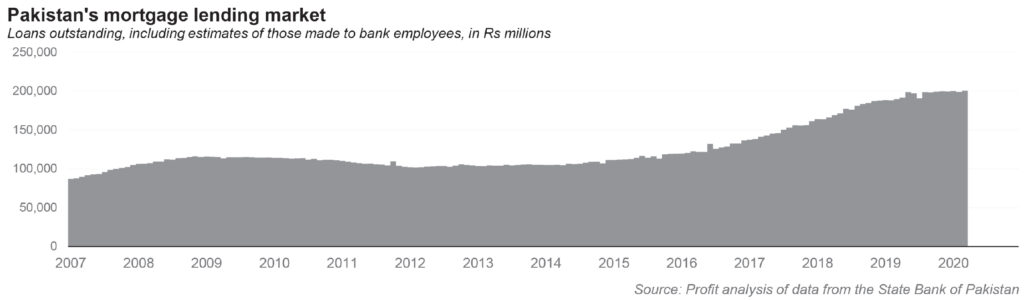

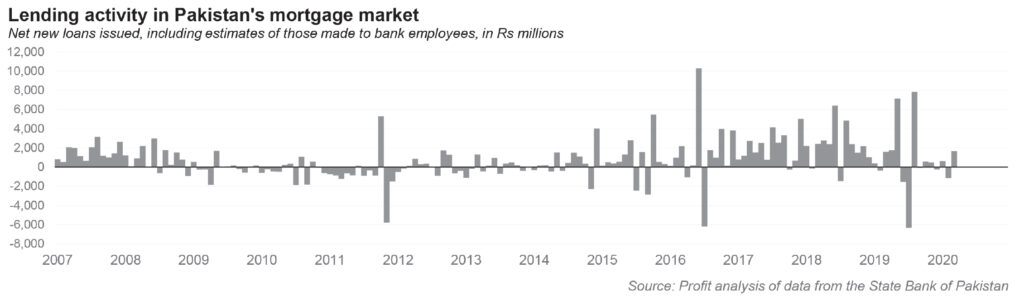

According to State Bank data, the volume of outstanding housing finance from banks stood at only Rs103 billion as of December 2019. This is an improvement when compared to the December 2018 figure of Rs92.4 billion, and the December 2017 figure of Rs82.6 billion. However, outstanding housing finance is only 0.5% of GDP.

That ratio, also known as mortgage depth, is abysmally low. For comparison, a country like the Netherlands has a mortgage depth of 83%. But one does not even have to look that far – in our region, both Bangladesh and India have a higher mortgage depth at 3% and 10% respectively.

The housing finance industry had two large problems: a lack of a legal framework, and the unavailability of long term funding.

On that first point, Khan pointed to a little known ordinance in Pakistan’s banking laws that caused a huge amount of headache for lenders: Section 15 of the 2001 Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance.

“This was Pakistan’s first attempt at a foreclosure law,” said Khan. Prior to the 2001 Ordinance, the law appeared to be biased in favour of borrowers, forcing banks to go through the full court case before they could recover the property from the loan defaulter. However, the 2001 Ordinance allowed banks to auction the mortgaged property of loan defaulters without obtaining a court order first. This would make lending to borrowers easier, since it would reduce banks’ risks.

However, in 2013, the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional, in that it did not adequately protect borrowers rights. The ordinance was then amended in 2015 and signed into law in 2016, before once again being struck down that same year, this time by the Lahore High Court.

That constant uncertainty kept the housing finance industry somewhat paralyzed, as why would banks lend if they could not recover property?

It is not to say that banks did not attempt to make an effort. According to Khan, there was a brief period in 2006-07, when interest rates in Pakistan were relatively low, at 5% or 6%, and banks began to focus on housing finance. But within the space of just a few years, the policy rate shot up to more than 14%. Since banks lend at KIBOR rates, the monthly installments shot up. “Somebody paying Rs10,000 installement, that installment became all of a sudden Rs30,000,” said Khan. As installment payments went up, people began to default on those loans, and banks witnessed a rise in non-performing loans.

This situation could still have been salvageable, if it was not for the same basic problem: there was no foreclosure law for banks to rely on. Frustrated by the legal system and scarred by the rise in non-performing loans, banks simply opted to not bother with the sector at all.

And it is not just the lack of a robust legal system. The housing finance industry does not exist in a vacuum. According to Khan, there was little to no regulatory oversight over the construction and real estate industry. For instance, there is a high number of benami properties in Pakistan, or property held in the name of one party, but paid for by another party. “It’s difficult to give finance for a property if you [the bank] are unsure about documentation,” said Khan. “All sorts of regulations were not there.”

While the real estate sector was under-regulated, microfinance banks were severely over-regulated. Prudential Regulations for Microfinance Banks before 2019 limited how much these banks could participate in housing finance. For instance, banks could only lend Rs500,000 to a single borrower, and had a regulatory cap of 40% for exposure above Rs250,000.

There was also a lack of housing finance companies, whose sole purpose was to provide loans for housing. According to Khan, there were one or two around the turn of the millennium. However, these shut down quickly, mostly due to a lack of long-term funding. The companies were often dependent on donors, and often could not raise funding from the capital market, as it was too costly.

Naya Pakistan – no, really

Obviously, this situation could not go on any longer. Something had to change, and between 2017 and 2020, quite a few things changed.

First, in 2017, the Benami Transaction Prohibition Act was passed, that was the first serious attempt at giving some semblance of structure to the real estate sector. (For comparison, India had passed similar legislation, back in 1988.)

Then in July 2018, the PTI’s Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme was announced, which aimed to give 5 million homes in five years. There was a Rs2.5 million (25 lacs) loan limit, with the loan tenors ranging between three to 20 years, and importantly, at a fixed rate of 12%.

It is still to be seen whether the scheme is successful (and based on previous federal government attempts, it is not likely). But the scheme is not as important as the spillover effects it had.

First, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) was unwilling to give loans for the new housing scheme, without a change in Pakistani law that allowed for banks to be able to recover money if the borrower defaulted. The 2001 Financial Institutions Ordinance, which had been languishing in court, finally got a new lease at life, as the Prime Minister appealed to the Lahore High Court Chief Justice. A date was fixed for the hearing in November 2019, and in March 2020, the court decided that the ordinance was constitutional after all.

The second spillover effect was that in March 2019, the State Bank issued its own housing policy recommendations. For the first time, Pakistan now had a definition for what low-cost housing actually is: the value of the house unit is up to Rs3 million, the area is up to 850sq ft, and the loan size is up to Rs 2.7 million.

The central bank also relaxed several requirements for all banks. For instance, banks no longer had general reserve requirements against low-cost housing finance portfolios. The loan to value ratio was reduced from 90:10 to 85:15. The minimum capital requirements for residential mortgage finance was reduced from 35% to 25%. Finally, a standardised loan application for all banks in Pakistan was also introduced.

Even microfinance banks got a bit of a break: banks could now lend up to Rs1 million, and the regulatory cap was completely removed.

So: the legal framework had been improved. As for the unavailability of long term funding, that is where the PMRC steps in. It is the final piece that is meant to work in tandem with everything else, to overhaul the mortgage industry.

Enter PMRC

The PMRC was incorporated in 2015, was classified as a development finance institution in October 2017, and commenced operations in June 2018, though it really began to work in around November of that year.

There are 10 shareholders in the company. The Ministry of Finance, the state-owned National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) and the state-owned House Building Finance Company (HBFC) together own 49.3% of shares in the company. The government put in Rs1.2 billion, while NBP and HBFC put in Rs600 million and Rs6.6 million, respectively.

The remaining equity came from the other banks, with Habib Bank (HBL) contributing Rs500 million, United Bank Rs500 million, the military-owned Askari Bank Rs300 million, Bank Alfalah Rs300 million, Allied Bank Rs200 million, Bank AL Habib Rs50 million and Summit Bank Rs1.8 million.

The State Bank allowed PMRC to operate with a minimum capital requirement of Rs3.5 billion, though for five years, the company cannot make any cash dividend to its shareholders.

The organisation was initially led by a Malaysian, N. Kokularupan Narayanasamy, but in 2018, Mudassir H. Khan took over as the CEO. “This has certainly been interesting and very challenging, to basically create a new market which did not exist before,” said Khan. “Here the board is new, they’re bankers, I’m a banker – I want to create and develop my role, and change the market for good.”

So, what are his aims? The PMRC is a mortgage liquidity facility set up by the State Bank. Think of the PMRC as a source of long-term funding for banks and DFIs. It does not provide its own housing loans, or mortgages, to borrowers; but it does purchase these mortgages from banks and guarantee them.

To do this, the PMRC is set up along the lines of mortgage refinancing companies in the developed world, such as Fannie Mae in the United States. (Yes, that Fannie Mae: the one that collapsed as a result of the US housing market crash in 2008, and had to be bailed out by the US federal government. Are we creating the exact same thing in Pakistan? Yes. Yes, we are.)

But just because there was a collapse in such institutions in the United States does not inherently mean that such a concept is unworkable, with the appropriate precautions.

So, how does this work? Banks can start a home loan, and can sell it quickly to PMRC. In fact any bank or development financial institution (DFI) registered with the SECP can sell to PMRC. PMRC then buys the loans extended by housing and commercial banks, and then sells them onwards to long-term investors.

To incentivise banks to work with PMRC, banks and DFI are exempt from cash reserve requirements (CRR) and statutory liquidity requirements (SLR) on borrowings from PMRC. According to the central bank, “these relaxations and incentives will aid PMRC in operating as a viable business entity on a sustainable basis.”

Where does PMRC get the money to buy the loans from banks in the first place? The company’s principal source of funding will be from the local bond market – which means that another objective of the company is to help develop the bond and sukuk markets’. PMRC will introduce a new asset class, conventional and Islamic mortgage-backed securities, for investors. These bonds will progressively have longer maturities than the current debt instruments in the market, and will have a yield higher than Pakistan Investment Bonds.

The benefit of having an institution like PMRC, is that once the bank sells its loans to the mortgage refinance facility, it has now freed up liquidity. This means it can now actually give out more loans to people, which helps in expanding the mortgage market.

The existence of PMRC means that there now exists medium to long-term funding for banks, which will help mitigate maturity mismatch risk, or when a bank has more liabilities than assets.

According to company documents, on a microlevel, if a lender faces liquidity issues during the life of the loan, the lender can now refinance existing loans through PMRC. On a macro level, this means there is generally more liquidity in a market. If there were to be a liquidity crunch in the market, the presence of PMRC can play a countercyclical role. This appears to be applying lessons learned from the US housing and financial crisis of 2008: allowing easier restructuring can go a long way towards preventing a crisis.

It is also a view echoed by Khan. “Our company has a dual role, it is to create the housing finance market, and then develop that to make it sustainable.”

“A house is a life-long, long-term asset for that family. Whereas it is funded by short term deposits of a bank. That is an asset-liability mismatch,” he explained. Khan wants to extend the tenor of a housing loan, keep the rates low, the installments smaller, and that way make loans more affordable. “That way the market will deepen,” he said.

Previously, banks shied away from long-term, fixed-rate mortgage loans. This something that the central bank has also stressed upon: “Housing finance is currently dominated by variable rate mortgages with no presence of fixed rate mortgages… Introducing fixed rate mortgages will provide needed comfort to the borrowers against fluctuating interest rates.”

But now, banks can get fixed rate funds from the PMRC, and thereby grant fixed rate mortgages to people. Fixed rate mortgages help reduce the incidences of defaults by borrowers – avoiding what happened in the late 2000s.

By the company’s own estimates, if the maturity of mortgage loans is increased from 15 to 20 years, that could lead to a 2% reduction in monthly instalments. Banks could even increase interest rates on mortgages by 1-1.5%, and borrowers would still have lower monthly payments. It is a win-win situation.

The company, since operating in November 2018, has amassed 11 clients. These include Bank Alfalah, HBL, Askari Bank, JS Bank, Bank Islami, First Women Bank, First Microfinance Bank, Thardeep Microfinance, HBFC, Habib Microfinance, and Orix Modaraba.

According to the latest company financials, in 2018, it had two clients who borrowed Rs1.2 billion. In 2019, the total exposure stood at Rs7.8 billion, against six borrowers. That number also includes around Rs1 billion in Islamic refinancing.

That Rs1 billion in Islamic refinancing is under a new product called Musharakah, which is the first Islamic mortgage instrument of its kind in the region. While other instruments exist in Muslim-majority countries like Oman and Malaysia, this is the first to be developed under the Hanafi Sunni jurisprudence, which is notoriously stricter about mortgage issues. “It was approved by the Islamic Sharia board and the State Bank, so I am looking forward to further innovation here,” Khan said.

Four clients have already borrowed in 2020, and Khan said that total financing increased from Rs7.8 billion last year to Rs11.5 billion this year so far. According to Khan, around 65% of new financing in 2019 was provided by PMRC – indicative of how small the market is.

Disbursements in 2019 were concentrated in Sindh, with Rs5.6 billion in Sindh, and only Rs1 billion in Punjab. There were no disbursements in KPK, Balochistan or AJK and Gilgit.

PMRC also invested in available-to-sell government securities, investing Rs5.4 billion in treasury bills, and Rs3.4 billion in Pakistan investment bonds.

PMRC has at its disposal around Rs17 billion allocated by the World Bank. Of that, roughly Rs8.5 billion has been set aside for low and middle-income housing, while roughly Rs7.1 billion was allocated by the World Bank as ‘‘Additional Tier 1 Capital’ for PMRC’s use. Around Rs1.6 billion is set aside for a risk-sharing facility. PMRC is close to signing an agreement with the Government of Pakistan for setting up a trust to offer a credit-loss sharing facility for low-cost housing.

According to Khan, most of the Rs11.5 billion borrowed comes from the World Bank’s pool of money. However, as noted before, one of the PMRC’s goals is to issue bonds to raise funds. So far, the company issued one bond with a valuation of Rs1 billion in March 2020. (Why have you not heard of it? Well, the PMRC did not advertise the event, as it felt most people were naturally consumed by the news of the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan.) The primary objective was to establish the pricing of the bond in the market. “By December, we expect that we’d be approaching the market again two to three times more,” said Khan.

Looking at the company’s numbers, one realizes that while PMRC has amassed an impressive number of clients in a short period of time, the amount of financing remains quite low. Despite the existence of PMRC, why are banks still so reluctant to take up PMRC financing?

Khan has a few theories. For one, though the Lahore High Court decision is favourable, there is an expectation that the decision will be appealed in the Supreme Court. It was that very court that had decided that the ordinance was unconstitutional in 2013, so according to Khan, banks will not rest easy until a final verdict is reached on the matter at the Supreme Court.

Second, despite the State Bank and government’s favourable policies, it will still take time for banks to ‘settle in’, as it were. The industry is still scarred from the experience of the previous decade of suddenly having a large number of non-performing loans in the previous decade. Still, Khan is not too worried. “With all these elements happening, with now the focus of the government on the construction industry and the housing market, I think we will see growth coming in the next year,” he said.

Looking to the future

In conversation, Khan still drew a distinction between the proposed government schemes, and what PMRC was trying to do.

“The Naya Pakistan housing scheme is still being rolled out, the impact hasn’t been felt yet,” he said. The process was long and cumbersome: first the developer industry would make the units, which would be bought by people, who would then need financing etc. But PMRC was about giving immediate financing this year.

In time, having regulations and having organizations like the PMRC in Pakistan could only have a positive spillover effect. “The private sector is slowly going to start entering this space,” he said. What Khan really wants is a pivot away from banks, who see housing finance as a small portfolio, and instead see the growth of housing finance companies, whose sole business is just that. “There are more than 70+ HFCs in India, there are none in Pakistan,” said Khan.

In fact, since the creation of the PMRC, three companies are now keen on setting up specialized agencies under the SECP’s non-bank financial institution rules; one has already been given a license. This could kick-start a whole chain of HFCs, if successful.

Khan is also optimistic that lower interest rates will also help the sector. “You’ll see more traction. With our discounted funding, these guys [banks] started producing products which are much lower than market prices. Now with market interest rates coming down…I expect a lot of growth coming in this sector, particularly in housing,” he said.

Once the housing sector takes off, according to Khan, then there is no stopping it. “Forty-five industries are involved in the construction of a single building. From the labour market, to steel and wood to light to tiles and bricks – you name it.”

“We expect the growth to be a minimum of 10 to 12pc, in 20 years maybe 25 to 30pc,” said Khan. “I would like to see the company sitting on a portfolio of 100 billion of housing finance in 5 years.”

But is that enough? Much of this article has been dedicated to explaining the scale of the problem at hand. The government, central bank, in some cases the judiciary, and now the PMRC, have in the last three years or so, formed a fragile but nascent environment, in which banks can start lending, and people can start the first step on their way to becoming homeowners.

But the level of poverty being described here, and the years and years of neglect, seem a little too insurmountable for one company with six transactions in a year to solve. It will take large scale, aggressive spending and building on the part of both the public and private sector. With a population of 212 million and growing – good luck.

The article seems to ignore the fact that from where the demand will come? Especially for a city like Karachi where all areas are super expensive and the property prices have gone up so high that they are out of reach of even middle to upper middle class. Noone kept a check on property prices here which increased by 5-6 times on average from their level in 2010. Forget about DHA, Clifton, PECHS, now even an area like Gulistan e Johar has no 240 yard (little less than 10 marla) house available under 3 crore.

This massive historic price speculation conducted by Karachi brokers (backed by provincial Govt) during the period 2010-17 was only possible because of acute shortage of decent housing societies in Karachi. In comparison, in Lahore everywhere you look around there are 100s of nice societies where you can find a plot and build a decent livable house. In Karachi there is only one location (namely DHA phase 8) where you can find a plot that is not outside the city limits. So obviously this artificial shortage led to massive price increases. With the doubling of property prices in DHA and Clifton after every 1-2 years, the property prices in remaining localities like PECHS, Gulshan, Johar etc just followed automatically as people didnt have any choice.

There is noone to address this as all the elite classes benefited massively from the game that was played during 201-2017 in Karachi property as their personal properties went up by 1 crore every year.

The ironic thing is that almost half of Karachi city area is barren. Instead of remote locations on superhighway where Bahria or DHA City was launched, the area on the west of Native Jetty (Tower) bridge till Hawksbay and beyond can easily be utilized to develop planned housing societies which are also not far from main city and just a 15 minute drive from there will take you to the financial hub. We are wasting such a beautiful naturally available coastal area from Sandspit till Gadani only due to Govt inefficiency.

The biggest housing crises and shortage is in Karachi, but the prices are so high that any scheme won’t work here. There is no use of this Naya Pakistan scheme launch in other cities like Lahore where already there is plenty of supply available at reasonable prices. Karachi property prices on average are double the level of Lahore prices even when the latter is much better in terms of living standards like cleanliness, greenery, road network and utilities infrastructure. It’s a shame everyone talks about housing crises but ignores Karachi.

It’s a shame everyone talks about housing crises but ignores Karachi.

Hi i am maha doong job in Pakistan media my salary is 50000 i want buy roof for me end mu family

Sir I am ghulam Hassan from hunza sust gilgit I need money help I have no job and if you help

Hi im from Lahore

I want a loan for a house

I am living on rent

Could you please email me your further details

Sir my name is sharoon ghouri

Respected sir/ma’am

Iam the children of an middle class family and we don’t have a perfect house to live and only we know that how we are suffering from many difficulties

Respected sir/ma’am it’s my humble request please help us

Thank you sir

Hello sir

I am Asim Ali from Lahore and I want to be a loan because I need new home and business so contact me ….

03049108432

Hy Sr AoA

I am Javed chauhdhr from Lahore and I want to be a loan because I need new home and business so contact me ….

03074415477 it’s arjent plz

Reply

Assalamualaikum

My name is arsalan from karachi Sir i need loan 25 lack

Hy zubair here from kohat kpk.. I need a loan of 5lac for my house construction .. Can u plz help me 03347275735 here is my contact number .

Sir am saneel chand from Pakistan I need loan house and business so can help me 03035626861

Sir aoa my name is amjad khan and i am soldier pak rangers sindh i live in karachi sir i need 10 lac loan to construct my home and i payback to installment so plz contact me cell number 0308.2029213.

Sir i need some money for for my family bills bay and other home need i can’t return money because my compny has closed in corana virus i am so mindly abset …me sirf dua kr skta hon aur dua k siwa kch nhi hai Allah sab ka madad gar hai ..Hamid Ansari

AOA I AM IRFAN FROM LAHORE I NEED HOME LOAN FOR REPAIR MY HOME IT IS FULL WITH WATER DURING THE RAINY DAY WATER IS COMING OUT FROM ITS FLOOR SO KINDLY ANY WHO GIVE MY LOAN AT MOST 250000 ONLY I SHALL BE THANKFUL BECAUSE I AM PRIVATE EMPLOYEE

THANKS

AOA I AM IRFAN FROM LAHORE I NEED HOME LOAN FOR REPAIR MY HOME IT IS FULL WITH WATER DURING THE RAINY DAY WATER IS COMING OUT FROM ITS FLOOR SO KINDLY ANY WHO GIVE MY LOAN AT MOST 250000 ONLY I SHALL BE THANKFUL BECAUSE I AM PRIVATE EMPLOYEE

THANKS 0321-4426754

i need support from any one for come out from the serious financial crisis. i have lost my work during covid-19 i have three childrens. Any can verify my situation. Please help me for survival and come back on track. Really appreciated and will awarded by God. 0309-2081445

Asalam o alaikum

I am facing financial instability due to covid 19 , have 3 children ,all are school going, want to start a small business and for this work needs loan up to 5 to 10 lacs.

Will you please help me to fix up this loan.

Thanks .

I have 7 marla plot in wapda town Peshawar required loan 5 lac rs urgently I will return back in installments

Plz reply me how can i get it

03224384485

Nicc

If you are real then contact me I am tell you how give him money and what is profit if your company is real then contact me my

Dear Sir

I want to build a house and need Rs.1500000. Kindly approve my case. Mr shall return in 5 years.

03444894816

This is the perfect site for anyone who wants to find out about this topic.

You know a whole lot its almost hard to argue with you (not that

I personally would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a

brand new spin on a topic which has been written about for decades.

Great stuff, just excellent!

i can not under stand english very well …pls tell me what is this ? how can we learn detail

For latest news you have to pay a quick visit the web and

on web I found this web site as a finest site for most recent updates.

Aslam O Alikum

Sir or Mam I Want To Loan 500000 Rupees Loan For My Refurnishing My House So Can You Give Me Loan For That It’s Behaf I Give You My House Land Papers Please Tell Me

Waiting…..

Sir please help me I am need small money. This year not working is business. This years tottly losses may request you please may help me may call number 03212300831 I am need 3 lac rupees loan I will return business run up.

A waiting your reply

Thank you

Assala my alikum

Sir

Main in dino baht preshan hon aor ap se request kar raha hon please mujy only 01 year k Lea 3 lakh de dain

03 Feb 2022 ko wapas kar don ga.please reply

What’s up mates, how is all, and what you desire to say on the topic of this piece of writing,

in my view its truly remarkable in favor of me.

Aw, this was a really good post. Finding the time and

actual effort to create a good article… but what

can I say… I hesitate a whole lot and don’t manage

to get anything done.

What’s up to all, because I am actually keen of reading this website’s post to be updated regularly.

It contains good material.

A motivating discussion is definitely worth comment.

I do think that you ought to publish more on this topic,

it may not be a taboo matter but usually people don’t

discuss such topics. To the next! Best wishes!!

Superb post however I was wondering if you could write

a litte more on this topic? I’d be very thankful

if you could elaborate a little bit further. Many thanks!

I am truly happy to glance at this web site posts which contains lots of

useful information, thanks for providing these kinds of data.

Thanks , I have recently been searching for

information approximately this subject for a long time and yours is

the greatest I’ve discovered till now. However, what in regards to the bottom line?

Are you positive about the supply?

Useful information. Fortunate me I discovered your site unintentionally, and I am shocked why this twist of

fate did not came about earlier! I bookmarked it.

Assalamualaikum

My name is arsalan from karachi Sir i need loan 25 lack 03361262002 my contact number please help me

Sir i m from norway live in oslo i have job at macdonald my home in pakistan i need homelon maiximum 7500000 sir can u reply me this and i m norwgin natinalti holder if posibel i take home lon sir can u reply me thanks

Mudssar Hussain

I m qari ammar i need home loan 03304527351