We live in the age of TikTok. Generation-Z and late age millennials, who were supposed to be the internet generation, are now facing an app that is beyond even them in many ways. Being an influencer today can mean a full time job that rakes in the cash. And it makes sense, what follows an audience is money and advertising, and if recent reports are anything to go by, influencers could soon be making shifts in the Pakistani advertising industry.

A combined forecast from the two largest advertising agencies in Pakistan has shown that advertisers are ready to shrink advertising expenditure by nearly 10%. This cut will come mainly from digital space budgets, with priorities shifting towards using content creators and influencers on social media apps. The logic is that advertising through influencers will allow companies to offset the restrictions in creative production created by the ongoing pandemic.

Advertisers are using these creators to endorse products for them or offer them to their fan bases at a discounted rate. According to data provided by Sensor Tower, these creators are spread across the top five apps in Pakistan: YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, and TikTok.

“Influencer marketing focuses on using social media influencers as a communication channel in the marketing mix,” said Jana Gross, chair of technology marketing at the Graduate School of Management at ETH Zurich. “Companies communicate through these influencers to a larger and targeted audience. Marketing with influencers on digital platforms has become a frequently discussed topic over the past years.”

Essentially, this means that companies send products or invites to events to influencers to get them to positively review their products, or use them in their content. At other times, companies also directly pay these influencers for short promotional work.

Depending on which advertising agency Profit spoke to, the scope of work of dealing with online content creators to push campaign messages was either categorised under a digital public relations (PR) practice or an influencer marketing practice. It was inferred that influencer marketing is a subset of digital PR for practitioners in both agency and marketer circles.

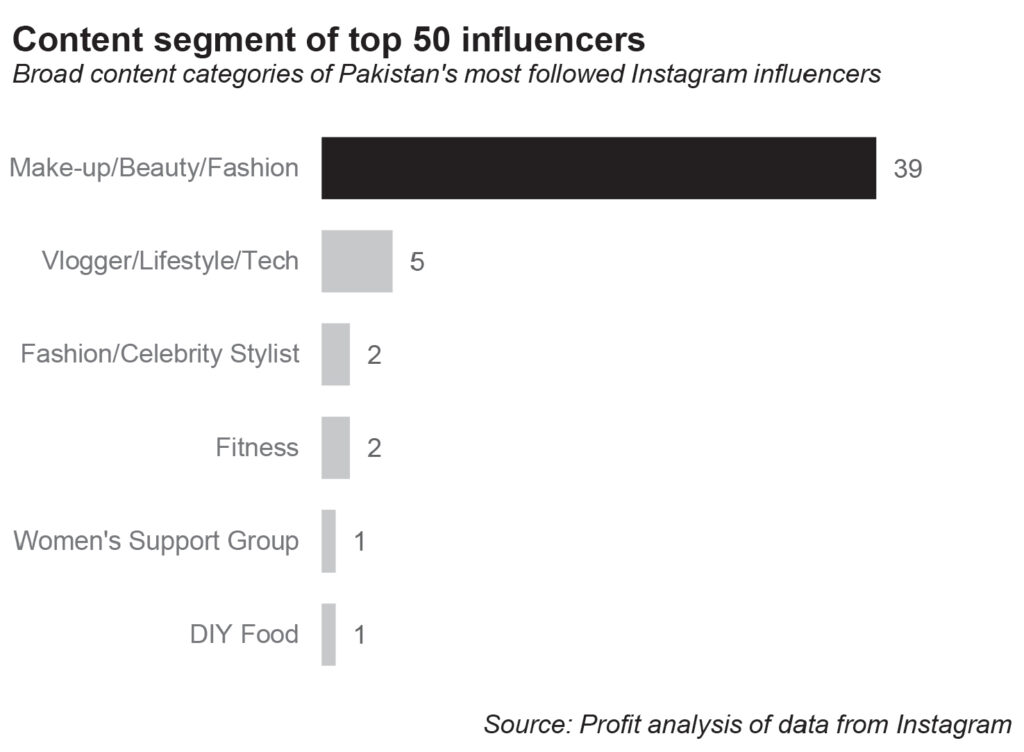

For the purposes of this study, we will be referring to the tactic of influencer marketing, which primarily attracts marketers that represent beauty, fashion, apparel, luxury, lifestyle, and food products. Profit examines the origins of this advertising tactic, the advertisers and agencies that have experimented with it, the stakeholders and players on the demand and supply side, and the black market that swindles advertisers that chase vanity metrics such as reach and awareness.

The origin of the influencer

Netizens are all too familiar with seeing their favorite online content creators, be it on YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, or even LIVEE, endorse a product or service and even offer discounts or exclusive deals by using a special coupon code. These online content creators either charge advertisers a flat fee or are offered a percentage of sales generated – sometimes both. Speaking to Profit, marketers said that when content creators preemptively offer themselves a higher fee for the latter, it creates trust and is one of the indicators of an authentic fanbase.

“[In Pakistan], food, cosmetics, technology, financial services, and others are all now moving towards engaging influencers,” said Adeeqa Nazir, the head of influencer marketing at Digitz. “The thing is that makeup bloggers have been there on Instagram and YouTtube way before [influencer marketing] became cooler and more widespread. They did their looks and all without specific brand endorsement and even to this day, they do brand integration instead of completely branding their looks/content with one brand.”

This trend started in 2016 with YouTube, when the largest video search engine and platform began to demonetise online content creators for creating content deemed either controversial or risky to brand safety. This impacted online content creators who focused on the news if they covered sensitive topics or cited centrist opinions. In some cases, a frivolous content copyright claim led online content creators to lose out on the ad revenue generated on the work they created.

These circumstances and more led online content creators to either ask viewers to support them on Patreon, a membership platform that allows online content creators to run a subscription content service and earn a monthly income, or securing deals with advertisers either through an internal sales team, an advertising agency partner, or a multimedia network such as Defy Media.

These creators, to their credit, ended up being shrewd. Instead of placing all their eggs in one basket, they also diversified their online presence outside of YouTube, with audiences on Instagram, Facebook, Twitch, and more platforms relevant to their content. Unlike YouTube, platforms owned by Facebook do not offer revenue sharing to content creators, regardless of how many views or engagement they generate. Online content creators that start off with a presence on any Facebook platform have to rely entirely on product endorsements and affiliate deals to sustain themselves.

And as the supply side has grown, with new content creators emerging on a daily basis, a new job has emerged from the chaos. If an online content creator has a genuine skill for attracting an audience, creating content against that audience, working with big brands to recommend a product and generate a return on investment against the said recommendation, they are deemed an influencer.

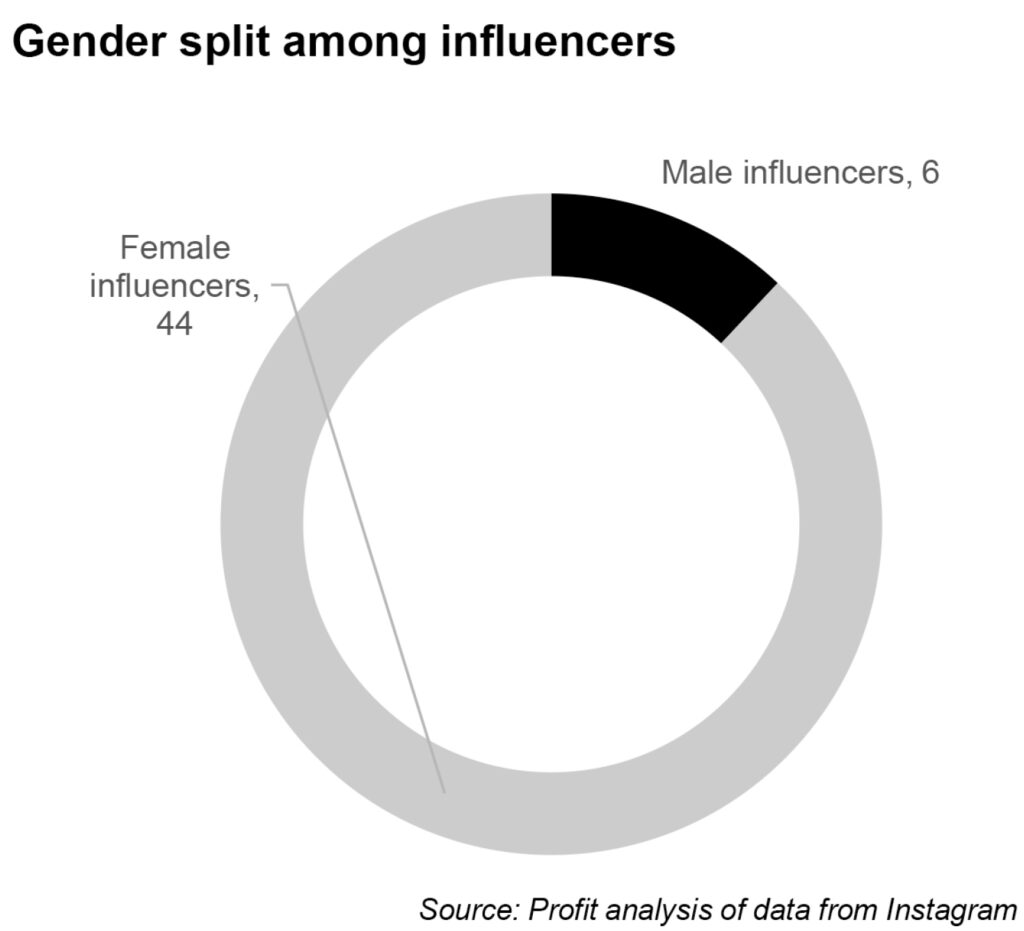

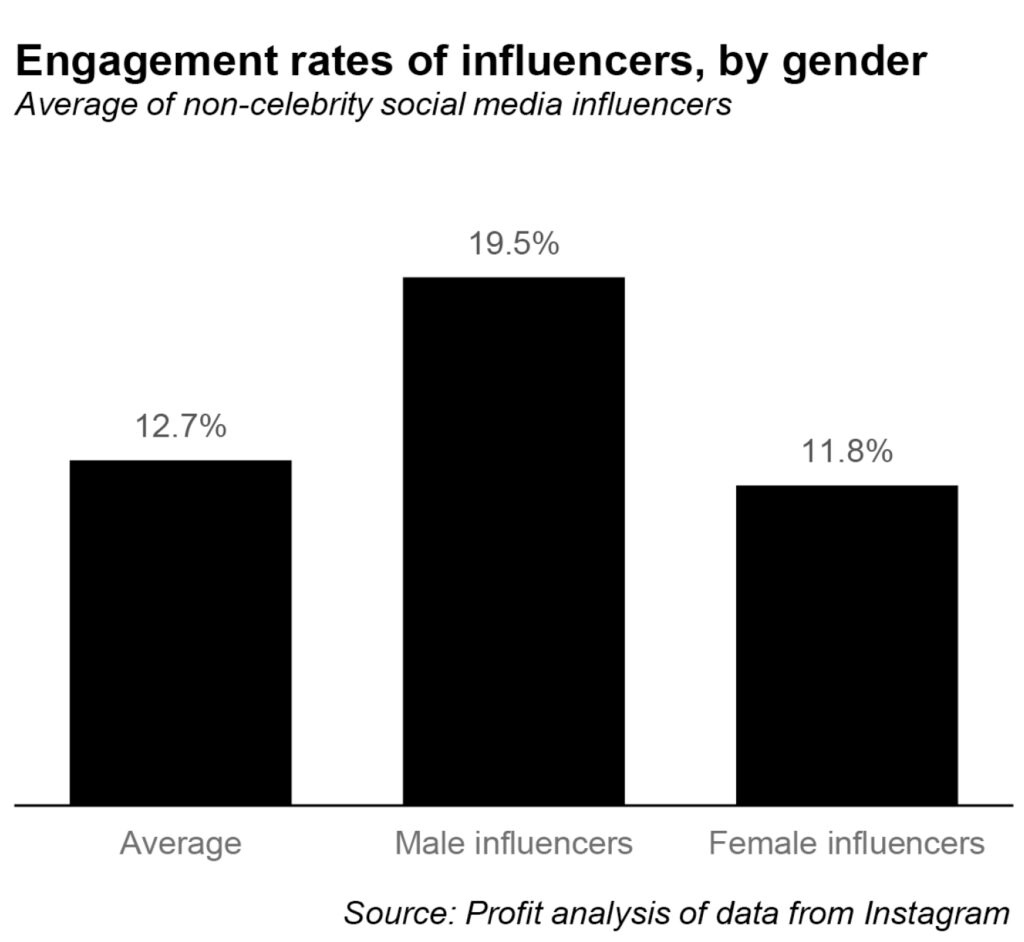

Agency executives told Profit that brand marketers are nine times more likely to prefer a female content creator than a male creator. On that note, Profit sourced a list of the top fifty non-celebrity influencers that digital agencies work with, of which 44 are female and six are male.

Aside from Altamash Javed, a Dubai-based filmmaker and cinematographer at ALJVD, all non-celebrity influencers shared with Profit peddle low involvement products, while ALJVD operates exclusively with high involvement luxury advertisers such as Audi and Apple, with whom he has been associated with for several years.

From the aforementioned list, Profit sought to rank influencers by engagement instead of by followers. But first, let’s acknowledge the unintended consequences of prioritising the one metric that can be easily faked.

Influencing and its discontents

“At Unilever, we believe influencers are an important way to reach consumers and grow our brands,” said Keith Weed, for chief marketing and communications officer at Unilever. “Their power comes from a deep, authentic, and direct connection with people, but certain practices like buying followers can easily undermine these relationships.”

The broker between influencers and brands is usually a digital advertising or public relations agency, with influencer worth calculated by the number of followers and content engagement. The latter is important, because while some influencers may have a lot of followers, their content may not be getting many hits. For this reason, they have to carefully craft their audience, and then companies also have to pick influencers that suit their product.

Stakeholders have told Profit that brand marketers often place greater importance towards following and engagement, with only about 25% of the value of any influencer to an advertising campaign placed on the quality of content produced. This focus on vanity metrics, created by the priorities of marketers who are measured by reach, has created a black market.

“Influencer marketing has led to the emergence of shady businesses called “click farms” which offer fake followers to influencers for a price, inflate the number of “likes” on their fan pages, and post spurious comments on their posts,” said authors of Influencer Marketing with Fake Followers.

“A quick Google search for ‘buy Instagram followers’ yields hundreds of results, where anyone with a credit card or Paypal account can buy hundreds of thousands of fake followers instantly. The rates for follows, retweets, likes, and comments are different based on the platform in question. Paquet-Clouston et al. report that click farm clients pay an average of $49 for every 1,000 YouTube followers. The corresponding figures are $34 for Facebook, $16 for Instagram, and $15 for Twitter. Average prices for 1,000 likes on these platforms are $50, $20, $14, and $15 respectively.”

Marketers that spoke to Profit shared that the most important metric for determining the worth of an online creator is the engagement on posts, calculated by taking the total engagement across the latest ten posts and taking out an average. This number is then divided by the number of followers. To do so, marketers and agency executives use tools such as Upfluence, SocialBlade, KeyHole, HypeAuditor, and Traackr to determine the worth of an influencers’ content, following, and possibly, their propensity to invest in brokerage services that peddle fake likes, followers, and views.

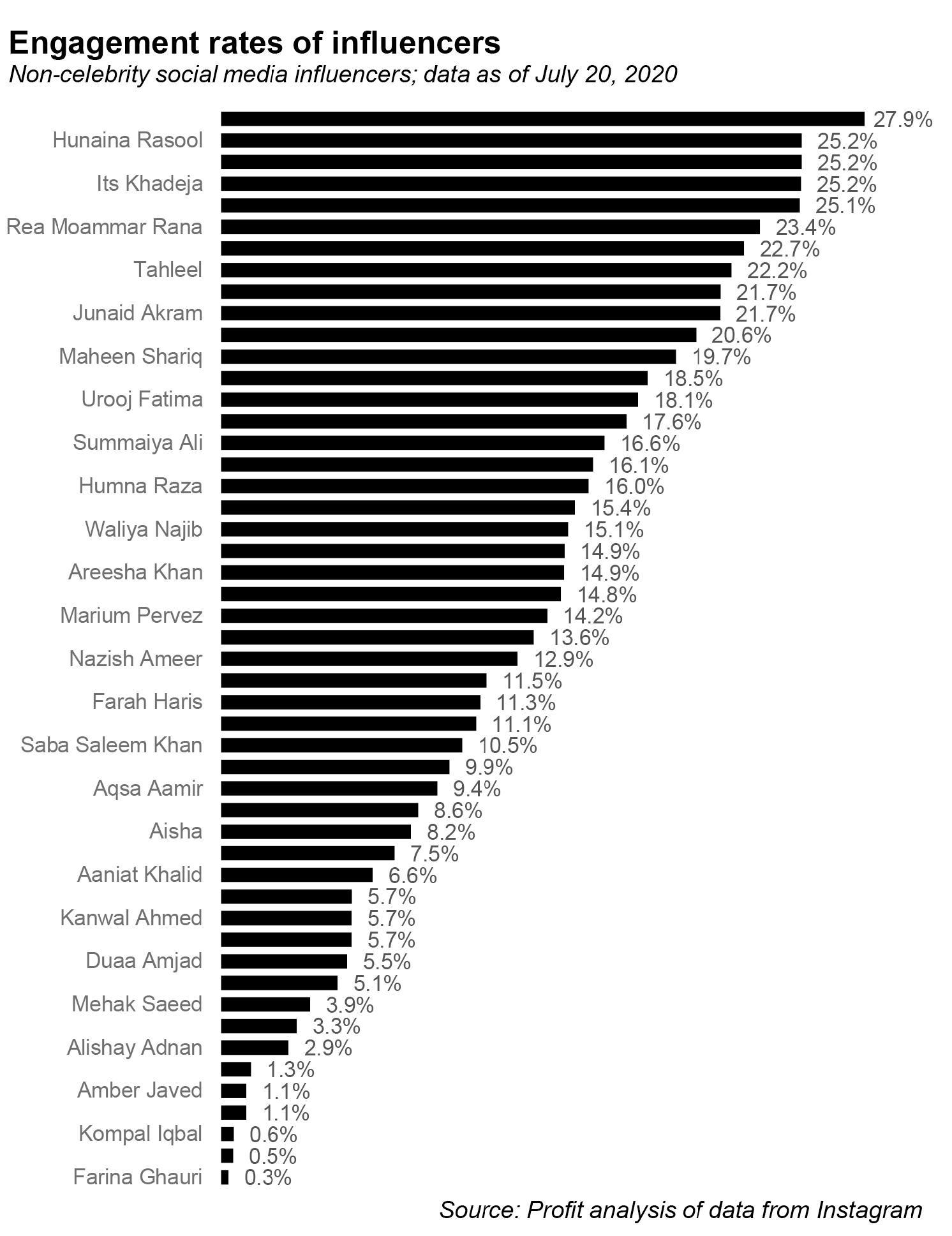

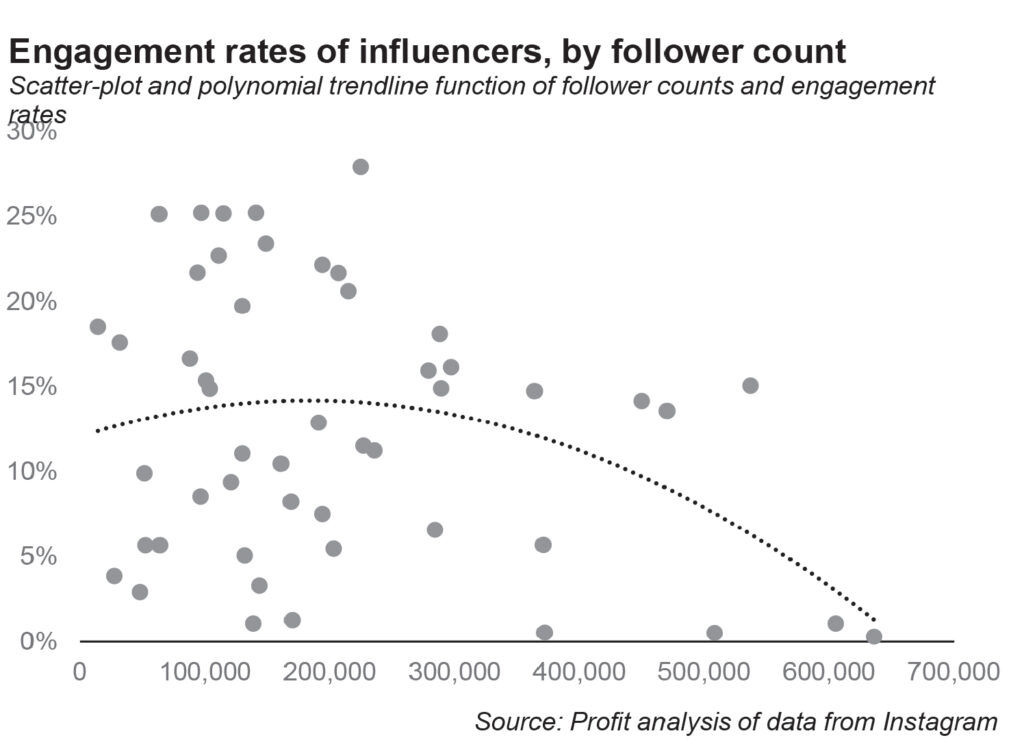

Profit was unable to gain a press pass to the influencer marketing measurement tools, with which we could determine which online content creators have used black market services based on unordinary spikes in engagement. Instead, Profit has analyzed the engagement of the top 50 non-celebrity influencers in Pakistan to understand their engagement, engagement per follower slab, differences in engagement for male and female content creators, the average engagement per gender, and how content creators market or segment themselves based on branded deals and organic content creation.

Analysis by Profit, independent of the aforementioned tools, found that as the follower count for an online content creator on Instagram rose, engagement rates plummeted (see attached charts).

The analysis was split between online content creators with over 600,000, over 500,000, over 400,000, over 300,000, over 200,000, and under 100,000 followers with their average engagement rates being 0.7%, 8%, 13.9%, 6.9%, 15.4%, 12.9%, and 14.6% respectively. Male content creators outperformed female content creators, engaging an average of 19.5% of their audience while the latter engaged on average of 11.8% of audiences, despite being the segment most preferred by marketers. This may at least partially be explained by the generall larger average follower counts of female influencers.

And even so, the likes, views, followers, and comments generated can and have been faked by using bots and private blogger networks (PBNs).

Profit also spoke to several online content creators, public relations agencies, and technology companies with a stake in the influencer marketing space, all of whom confirmed the unregulated social media marketing tactic is rife with advertising fraud, which most brand marketers having no interest in addressing, investigating, or running any due diligence on the scope of said fraud due to incentives around reach instead of depth.

Online content creators and advertising agencies told Profit that when a client-side marketer [industry lingo for the companies that actually pay for their products to be advertised, such as Unilever, Nestle, Engro, etc] has a vested interest in generating sales using influencer marketing, they are concerned about engagement fraud and try to weed out creators that have resorted to PBNs or fraud to boost their numbers. On the other hand, client-side marketers who have a vested interest in vanity metrics such as reach and awareness, Profit was told, have no interest in conducting any form of fraud assessments.

With the majority of client-side marketers falling into the latter category, a black market has emerged in Pakistan consisting of brokers offering bots or ‘organic’ fake followers, with the brokers being either freelancers found on Fiverr or members of public relations agencies helping an up and coming model or celebrity be known. A simple Google search pertaining to Pakistan on the subject will lead results, some of which are using Google Adwords to peddle their services.

The real worth of an online content creator, Profit was told, is their ability to drive the loyal fans to purchase the products which the creator has been paid to endorse or push. Advertising agency executives told Profit that if an online content creator can drive commercial results for a sponsor that represents at least 10% of their total audience, agencies begin to refer to that creator as an influencer.

“Because of the dramatic growth and diversity of influencers, one core challenge is to identify and select the right type of influencers for a given campaign,” said Gross. “Influencers differ in content, social presence, actionability, and reach. Additionally, influencers within the same vertical distinguish themselves through personality, domain, or topic. Vertical refers to the broader area to which the influencer’s content can be categorised in, for example sports. The domain is a particular sub-vertical within the focal vertical, for example angling. However, at the end of the day, a clear and consistent identification of influencer types is fundamental for a successful influencer campaign.”

The second challenge in this space is the lack of regulation in Pakistan that results in influencers failing to disclose the commercial nature of their product endorsement. A campaign by McDonald’s featuring Ali Gul Pir around the bun kebab burger was revealed to be sponsored only after the product had been launched nationwide. A similar instance occurred with Junaid Akram visiting a Haleeb Foods plant, telling his fans it was an organic invitation based on a video he did on factory hygiene standards. It was in fact a trust-building campaign initiated by and coordinated with the advertising agency Interflow Group’s digital arm DHQ.

“The use of digital influencers to expand a brand and increase business is on the up,” said Christine Riefa, a reader of consumer law at the Brunel Law School. “This creates new difficulties in ensuring consumer protection. Digital influencers provide reviews and endorsements of products usually through social networks and presented as personal endorsements.”

“Practices have been identified where digital influencers do not adequately disclose whether their review or endorsement has been paid for or if they have a financial relationship with an advertiser. This creates a lack of transparency and ability for the consumer to recognize content that is in fact paid for.”

Best practices in influencer marketing

As stated above, within the scope of social media such as Instagram and video platforms such as YouTube, advertisers have the option to utilise self-service campaign rollout tools to reach their target audience. In taking the influencer marketing route, advertisers do not have to spend money directly with platforms and instead hand over fees to either the influencer themselves or the digital agency intermediaries.

“One main difference between influencers and other key players is that the border between content creation and consumption vanishes. In contrast to celebrities or opinion leaders, influencers create content for their audience and consume the traffic generated by their content,” said Gross. “They highly appreciate audience comments and take audience feedback very seriously, thereby being influenced by their audience.”

She goes on to explain that based on the goals of a campaign, the exact target audience, and the message of the influencer campaign, companies should then decide whether to put a focus onto domain breadth or onto social presence.

The former refers to influencers that have subject matter expertise while the latter refers to influencers who simply attract an audience based on their optics. She said that making the distinction honestly plays a big part in achieving the stated campaign goals, adding that once the focus is defined, companies should identify which of the four influencer types best matches – citing The Big Four of Influencer Marketing. A Typology of Influencers, a research paper she co-authored on the types of influencers and their best fit to brands and campaign goals.

“Influencer marketing is a highly dynamic, fast-moving and growing channel,” said Gross. “When examining the trend of influencers, it becomes clear that new influencers emerge every day. It is therefore important for companies to have a guideline that can be applied when scouting influencers. In sum, it is recommended that companies should first define the target audience to be reached. Secondly, on the basis of this, they should define the goals of their influencer campaign and the message to be communicated.”

Sarah Hughes, a product marketing manager at Inmar, says that selecting the right influencer is often one of the most complex pieces of campaign planning, made worse when marketers struggle with audience legitimacy and brand affinity data. She said that surface level data like followers, engagements, and content quality will no longer cut it for influencer selection.

“In our research, which was conducted using AI-driven selection technology, we found that influencers selected via AI had a higher brand affinity and higher estimated impressions than influencer selected by a client,” she said. “Instead of using vanity metrics to measure the success of your campaign, use this information as a diagnostic tool for real-time campaign optimization to determine which channels, content, or messages resonate most with various audience segments.”

The good, bad, and the ugly

Speaking with Profit on the condition of anonymity, an executive at Mumuso shared that a recent integrated marketing campaign employed 15 online tactics for customer acquisition. Profit was told that the worst-performing tactic was influencer marketing channels, with a $400 flat fee paid to Areeka Haq. Out of her 1.3 million followers, 36% watched the sponsored content, and only 0.41% clicked through to the site link of which a grand total of three people purchased $35 worth of products. Even with the assumption that Mumoso was mistaken in its selection of influencers, the negative return on investment is so jarring that the business will never experiment with the tactic ever again.

“A successful, measurable, impactful influencer program is all about the process: research and planning, influencer selection, activation and optimization, and measurement,” said Hughes. “Use data to uncover information like shopper behavior, category trends, and audience demographics prior to selecting influencers and kicking off your campaign. Creating a campaign that is built and designed by data is the first step to a successful program.”

The most prominent use case for influencer marketing in Pakistan has been to create awareness and generate trials, with limited attempts to connect the tactic with cold hard sales which cannot be doctored through bots or PBNs. Unilever Pakistan Foods Limited (UPFL), a long-time user of influencer marketing, recently rolled out a campaign utilizing micro-influencers on Instagram for Wall’s Solero, which has thus far attracted nearly 250 unique posts at an unknown average awareness rate.

Across nearly 200 posts seen by Profit, there is no affiliate link, no coupon codes, and no ‘link in bio’ copy. The campaign only employs hashtags to measure awareness and audience growth. This approach of valuing awareness over commercial results corresponds to what Profit is told is the root cause behind the black market for bots and PBNs, with advertisers that are employees preferring measurement in this way.

“The final step to ensure a successful influencer campaign is to define your measurement strategy,” said Hughes. “Your post-campaign measurement strategy should correlate to your main campaign goal. For example, if your campaign goal was to increase in-store sales, you would want to use a retail sales lift analysis to measure the success of your influencer program.”

In direct contrast, a sales-focused online campaign launched by Tudors Pakistan has activated nearly a dozen influencers, all of whom have been given a 10% coupon code that corresponds to their Instagram handle or name, according to documents seen by Profit. Fans and followers of the selected influencers can avail discounts as a result of the code, and the influencer will be compensated in the follow-up campaign based on the revenue generated, much like the affiliate marketing model. The decision-makers behind this campaign have a vested interest in delivering commercial interest and sales, and thus are less concerned about awareness and audience growth, pushing sales and earning reach and views as a consequence.

“When large advertisers start measuring influencer marketing campaigns with sales and calculating influencer worth with their ability to drive commercial results – which no bot or PBN can fake, we will see the market shift to influencers with domain expertise instead of those that just look good for the camera and have a tharki audience,” said a prominent publicist.

“Till then, advertisers will continue being defrauded and waste their money during a recession. Strange that even in times of austerity, advertisers at MNCs are wasting money on vanity metrics. When the large advertisers evolve their approach, the market follows. Till then, they are asking to be duped and the market is more than happy to profit from their ignorance.”

Additional data analysis by Taimoor Hassan.

Nonsensical reference to Mumoso. I think they had an amazing “brand awareness” response – $400 flat fee paid to Areeka Haq. 468k PEOPLE watched sponsored content signifying fab reach! If it cost US$0.01 for a unique view on a paid ad network, they would have to pay US$4,680, 10x more than what Areeka was paid. biased reporting

Out of 468k people, only three purchased the product. The industry wide conversion rate with SMCCs is 1% so if her followers were not problematic, the client would have seen 4.68K people make a purchase.

For adverting business on social media is best way