One of the most searched topics on Pakistan’s economy is the “richest Pakistanis” list: some form of authentic measure of just who are the richest people in Pakistan and exactly how rich are they? Catering to this demand are a series of webpages that look like they have not been updated since 1998, some of which have some useful information, but most of which appear to be filled with rectally derived statistics.

We do not wish to keep you in suspense. This story is not Profit’s attempt at creating that list. That is a project that is ongoing (and has been for at least three years) and believe us when we tell you: when we pull it off, we have no intention of being subtle about it.

No, this story is an examination of who owns the largest companies in Pakistan and derived in large part from a study conducted by Nadeemul Haque and Amin Hussain at Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE). Haque, as readers of Profit would know, is currently the vice chancellor of PIDE and an economist with a longstanding career in both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the government of Pakistan. Hussain is an economics doctoral student at Uppsala University in Sweden.

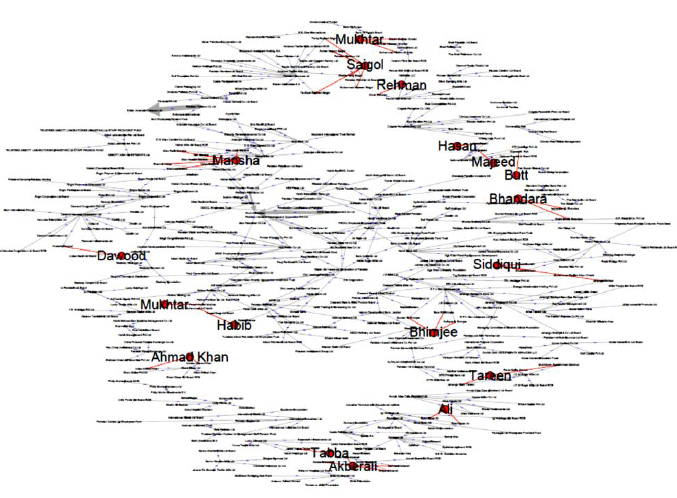

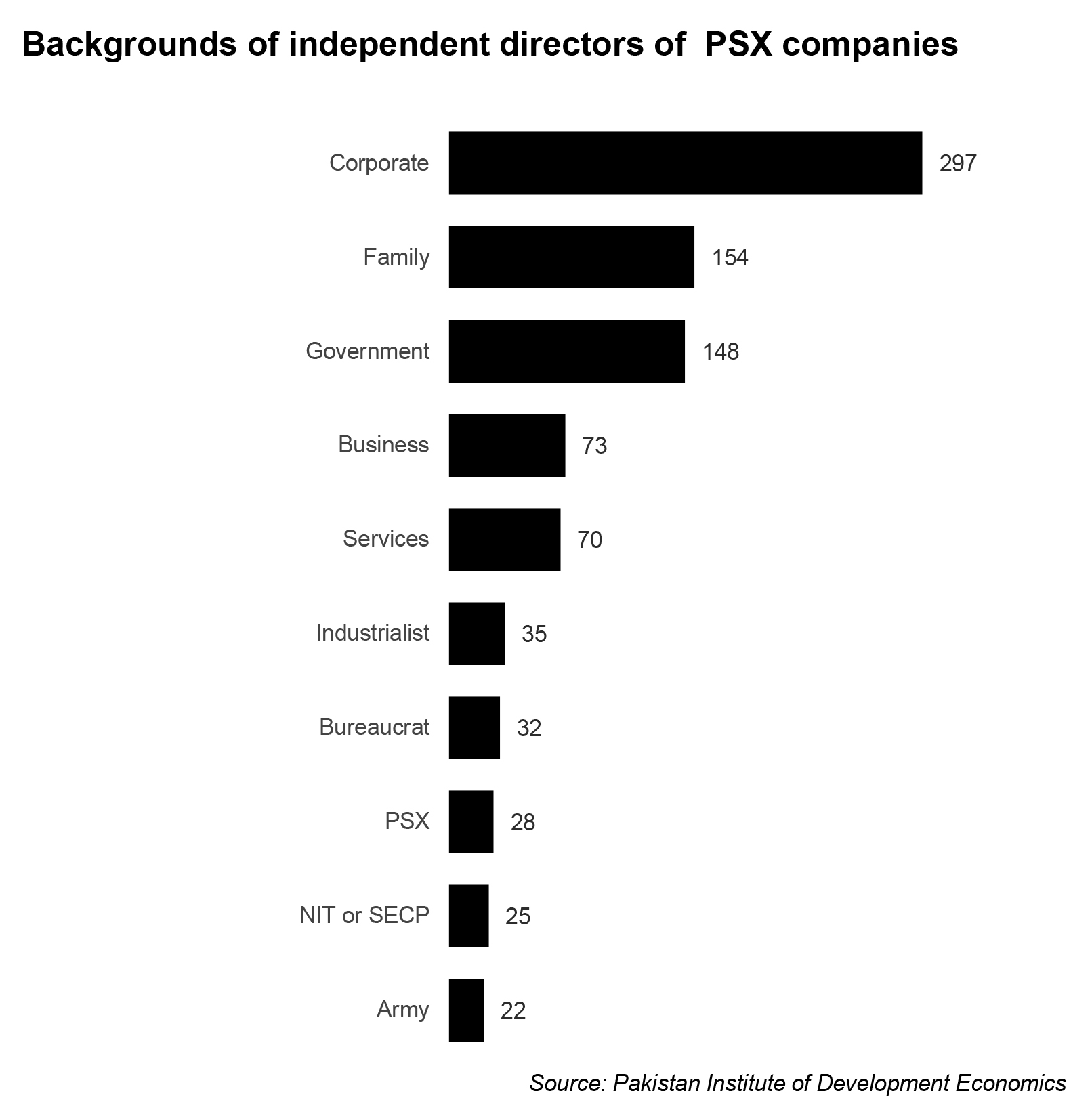

What they find in their study is fascinating: most Pakistani publicly listed companies are either owned by the government, multinational corporations, or by a small network of 31 families, most of whom exercise relatively tight control over what are ostensibly supposed to be public companies.

In this story, we at Profit will lay out some insights from that study – who are the biggest owners of businesses in Pakistan, and how tightly do they exercise control – but we will also go one step further. We will highlight how the structure of ownership has changed over time, and what that means for the nature of wealth creation in Pakistan today. We will also lay out our own case for why our interpretation of the data is perhaps more optimistic than that of the authors of the study.

But most importantly, perhaps, we will lay out the evidence behind our biggest assertion: that the wealthiest families and entities in Pakistan today are all owners of legacy businesses, and that the future of wealth creation will come from industries entirely different from the ones that account for the great Pakistani fortunes of today. Those among the current crop of wealthy families who see this, and decide to make the pivot will continue to be on this list 20 years from now. Those who do not will vanish like the more than two-thirds of the infamous Ayub-era 22 families.

A note on methodology (feel free to skip)

The study undertaken by Haque and Hussain is a point-in-time snapshot of who owned shares in publicly listed companies in the Pakistan Stock Exchange. For this, they examined the companies that comprised the benchmark KSE-100 index as of 2018, and used what appears to be annual report data on shareholding patterns from that time.

While the companies that comprise the KSE-100 index do not constitute the entirety of the universe of publicly listed companies, they do account for the largest ones and collectively constitute more than 80% of the market capitalization of all companies listed on the exchange.

Our biggest critique of their methodology is that use of annual report data rather than a more exhaustive list of shareholders that could be obtained from the Central Depository Company of Pakistan (CDC) or other share registrars. Using the latter source might have uncovered even more patterns than they were able to find using annual report disclosures. Nevertheless, what they have put together is still very impressive.

One other minor critique: companies do not have annual reports issued at the same time since many companies have different financial years, with some running from July through June (most energy and textile companies), and others running from January through December (most financial institutions and multinationals), and still others running from October through September (sugar mills).

That makes the point-in-time analysis of shareholding patterns slightly asynchronous. This is a minor defect, however, and one unlikely to substantially change the result since shareholding patterns do not materially change over the course of one year (though they do over several years).

We would argue that an intertemporal analysis would have been even better (and certainly one we plan on conducting ourselves in the future), but this is probably too nitpicky on our part. The broader insights offered by the study are fascinating, and we will now present them below.

Who owns what?

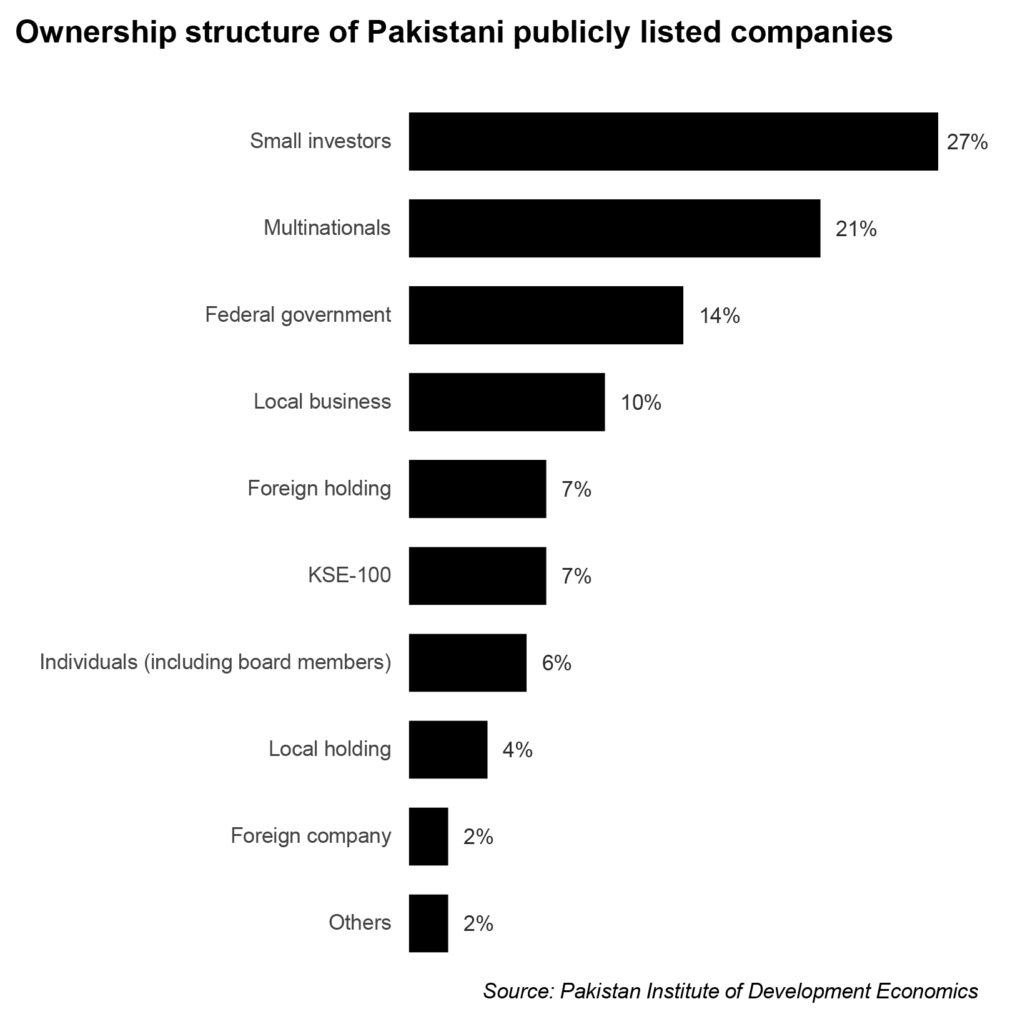

You would not know it from the headlines, but the single biggest category of owners of shares on the Pakistan Stock Exchange are small investors, who collectively own 27% of the value of companies listed on the PSX. The category that the authors of the study list as “small investors” largely consists of mutual funds, and other institutional investors that rely on retail investors for the bulk of the capital they have available to invest.

The study has a second category called “individual investors”, which is somewhat of a mixed bag, since it includes people who are on the boards of directors and managing shareholders. (This is where using the CDC and share registrar data would have helped disaggregate the data into more relevant categories.) Shareholders in this category own about 6% of the total value of shares listed on the exchange.

The second largest are multinationals whose subsidiaries are locally publicly listed (21%), followed by the government of Pakistan (14%).

All of these categories are dwarfed by the local shareholders who own publicly listed companies through other types of holding companies. The Haque-Hussain study breaks this out into four subcategories, but collectively they control about 28% of the market cap of the KSE-100 companies. The subcategories are locally incorporated holding companies (4%), foreign incorporated holding companies (not multinationals, but local groups that simply have a foreign holding company, 7%), other KSE-100 companies (7%), and local businesses (which often consists of unincorporated groups, 10%).

Employee shares, provincial governments, foreign companies (not majority shareholders), and the National Investment Trust (NIT) round out the rest.

What does this data tell us? Mainly that the vast majority of shares are clearly owned by the controlling stakeholders. This is consistent with the fact that the free-float of the Pakistan Stock Exchange – the proportion of shares available for trading on any given day, that are not locked up by the long-term owners – is approximately 30% of the total market capitalization of the PSX.

In essence, the controlling shareholders want to maintain as much control as possible while still getting the advantages of being publicly listed. This, by the way, is often portrayed as a problem of Pakistani family businesses wanting to remain in control of family businesses, but the truth is that the Government of Pakistan and multinationals sell even less of a share of their companies than local business families. The problem, in short, is not seth culture, but the general control freak nature of people doing business in Pakistan.

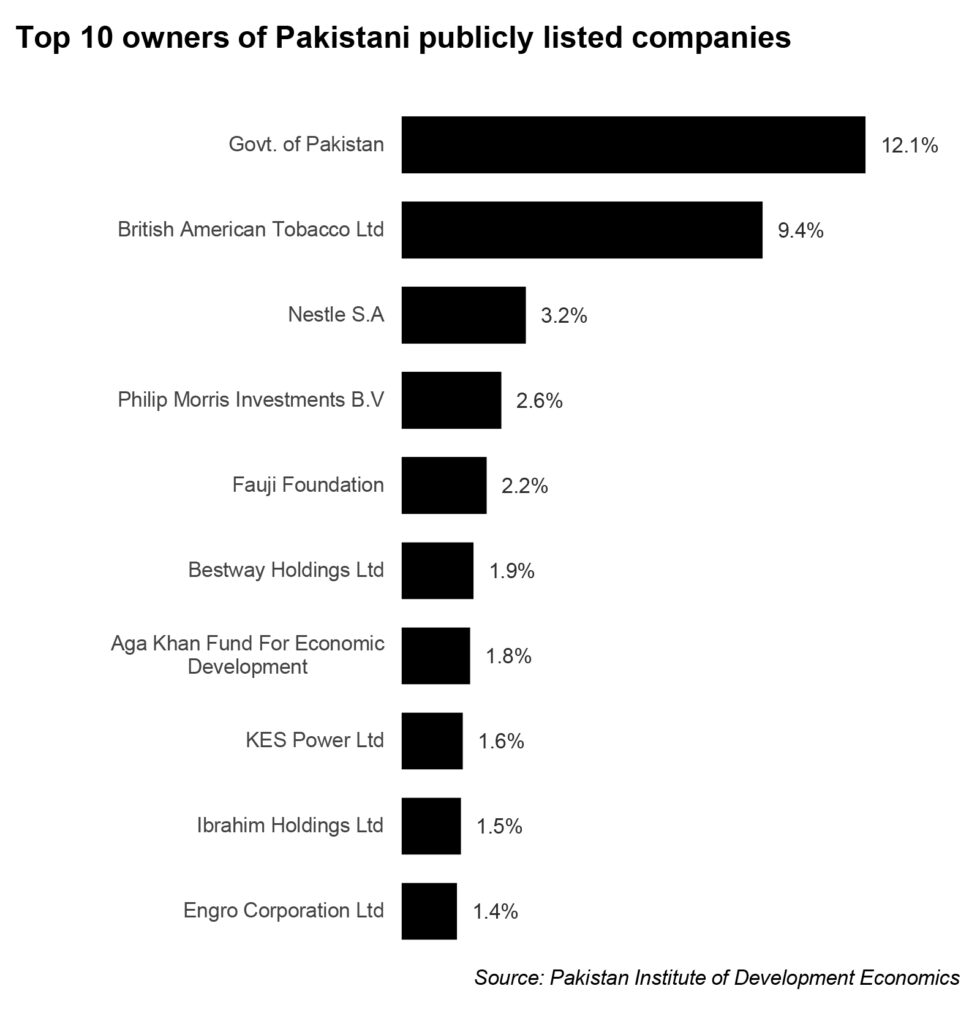

More importantly, the seths are actually smaller and less powerful in terms of absolute economic value of their companies than they appear in discussions about Pakistan’s political economy. Compile the list of shareholders by entity, and the top 10 is absolutely dominated by the government and multinational corporations and investors. Only two of the top 10 are local business entities: Ibrahim Holdings, and the Engro Corporation.

This, by the way, is not at all to suggest that Pakistani oligarchs do not have outsize power and that the rules governing Pakistan’s economy are somehow fair. Large business groups in Pakistan absolutely do have a lot of influence on government policy – too much, in our view – and the rules are rigged in their favour. But what we believe the data highlights is this: it does not take a lot of money to become an oligarch in Pakistan. You most certainly do not need to be a billionaire in US dollars.

In other words, the Pakistani establishment can be bought on the cheap and made to do your bidding, all for a trifling amount of money. How else does one explain the extraordinary lengths to which the government goes to protect the interests of businesses that are – by global, and even regional standards – medium-sized businesses at best?

Changing nature of ownership on the PSX

What is especially interesting about the study conducted by PIDE is how different the 2018 data looks from the 2008 data. While we at Profit do not have as exhaustive a documentation of the ownership structure of the PSX from that era (at least not yet), we do have some data points that indicate how much things have changed, and have important implications for the direction of change.

The single most important factor is the government’s diminished role as a dominant shareholder on the PSX. Back in 2008, more than 35% of the market capitalization of the then-Karachi Stock Exchange was owned by the Government of Pakistan. About 20% of that was the government’s shares in the Oil & Gas Development Company (OGDC) alone.

Ten years later, the proportion of the country’s publicly listed companies owned by the government is two-thirds lower than it was back then. How did that happen? Two privatization transactions helped, to be sure, but the bigger culprit is the fact that the government of Pakistan’s businesses grew a lot slower than the rest of the market, which meant that their share of the overall market capitalization declined because the other companies grew faster.

Why did the government’s share decline? Because the Government of Pakistan is much more interested in the cash flows from its portfolio companies’ dividends than it is in allowing those companies to reinvest their cash flows into growth-oriented projects. That, and the government’s biggest holdings are in industries in decline. Domestic oil and gas reserves are declining, which means that OGDC and Pakistan Petroleum (PPL), for instance, will be worth less in the future than they are today. OGDC and PPL still account for a large plurality of the government’s share of publicly listed companies.

Then there are the foreign companies, which together account for over one-fifth of the market currently. This share is only slightly higher than it was in 2008, but what makes it extraordinary is the fact that it continues to be so high despite the delisting of Unilever Pakistan from the stock exchange. Before it delisted, Unilever was one of the largest publicly listed companies on the KSE. On a like-for-like basis (meaning, excluding Unilever from the 2008 calculations), multinationals have grown their share by more than a third.

That means that multinationals have grown faster than the rest of the market. How does that happen? Well, yes, it is true that multinational corporations have access to both larger amounts of capital and a lower cost of capital than most local conglomerates – even the largest ones – but a bigger explanation for their dominance is likely the fact that the most talented Pakistanis prefer working for a multinational employer over a local one. Winning the race for talent likely allows them to come up with better ideas for their businesses and thus grow faster than their local rivals.

Little overlap in the “31 families” and the “22 families”

To say that Pakistan’s economy was dominated by 22 families in the Ayub era and is now dominated by 31 families – as most news coverage of this study have done – is to imply that the club of 22 remained intact and grew slightly larger. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Only five of the original 22 families – the Habibs, the Dawoods, the Saigols, the Babar Ali family, and the Bhimjees – are part of this club of 31 families in the current era. The rest of the 22 families are not exactly poor, but today their descendants tend to be on the upper end of upper middle class rather than the wealthy captains of industry that they were in the 1960s.

The rest of the 31, on the other hand, are those who were upper middle class in the 1960s – or even lower in some cases – and rose up through either entrepreneurial ambition, or proximity to powerful politicians, or both. This is very important to note because what it means is that wealth in Pakistan is not something static that simply gets passed down from generation to generation, and that some can rise while others can fall.

We would like to claim that this is due to the normal course of a market economy, but the truth is that in Pakistan, this upheaval took place in large part due to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s nationalization drive in the 1970s and its aftermath in the 1980s. Not everyone can trace their wealth to that upheaval, of course. Jahangir Siddiqui, for instance, made his money entirely independent of any government intervention. But most of the 22 who are no longer in this club lost their wealth due to government expropriation, and at least some of those who gained it were ones who were the beneficiaries of the government selling those assets back to the private sector on the cheap after having destroyed them for over a decade and a half.

Those on the left of the political spectrum (Kaiser Bengali, I am looking at you) would argue that this data point proves that nationalization was a good thing and that privatization should never have taken place. We, quite obviously, disagree and would point to the fact that functionally, Pakistan deactivated its industrial base for over two decades (1977 through roughly the start of the Musharraf era) before it was able to get back up the levels of industrial activity last seen in the 1960s. Was that a price worth paying? Surely, a better taxation policy would have sufficed in addressing the inequity.

And, much more importantly, the nature of wealth creation in Pakistan is about to change and make it more diffuse. The oligarchs of old will either have to adapt or else watch their fortunes wither on the vine as a newer generation of entrepreneurs scales the commanding heights of wealth in Pakistan.

Golden handcuffs

The key defining feature of the fortunes of the richest Pakistanis today is how much they are industries of the past. There is not a single fortune made in the technology sector, for instance, and most of the companies do business that is not too dissimilar from the kind of companies that existed a century ago. Cement, sugar, banking, insurance. You could go back 100 years and there would be companies that were in those business lines.

There is nothing inherently wrong with these kinds of businesses, of course. But if the last decade has taught us anything, it is that there is no faster and better way to make money than to transform what the world around you looks like. That often means the technology industry. While working in analog industries was enough to make a fortune in the past, whether or not it will be enough in the future is an open question.

The fortunes of those today, by and large, require good relations with the government (and by extension, politicians and the Army) even if political connections did not play a role in the creation of those fortunes. That makes the current system inherently closed off to outsiders and challengers. Technology – particularly software – is different. Anyone with an internet connection and the ability to read and understand basic mathematics has the potential to be able to learn how to write code and create a business that could become incredibly valuable. That completely changes the barriers to entry on making a great fortune.

It also means that – if share of total wealth, or ranking among the wealthiest, are the metrics being used to assess great fortunes – then having an old cement factor or textile factory will not be enough. The business that makes you your money will have to have a transformative impact on the economy if you hope to retain your position at the top of the Pakistani economic pyramid.

Put differently, who would you rather be: Muneeb Maayr (founder of Bykea) or Mian Mansha (chairman of MCB Bank)?

This is not to suggest remotely that the current economic elite is not investing in the future. After all, two of Pakistan’s largest venture capital funds are at least partly sponsored by family businesses: Lakson Ventures (the Lakhanis) and Fatima Gobi Ventures (partly invested in by the Mukhtar family). These funds are investing in some of the most innovative companies in Pakistan, and the families backing these funds will likely retain their place in the pantheon of the Pakistani economic elite.

But for many others, the temptation will be to stick with the companies and businesses that they know, especially since those businesses continue to yield massive amounts of cash flow that allow them to lead incredibly comfortable lives. When the world is going your way, it is very difficult to see that it is about to turn against you.

Having a great fortune now can be a pair of golden handcuffs, chaining the owner of that fortune to the means that got them there. Only a handful of people have ever been able to pivot away from the business that generates surefire cash and take the risk towards a completely new set of technology and business with much greater risks and much greater chance of failure.

The odds are that the list of the richest Pakistanis will look very different over the next 20 years, with more and more people who have made their money in technology, and fewer people who own old-school businesses.

Looking at a list of great fortunes of today, in short, is a bit like looking at the stars: you are seeing the brilliance that originated long ago. It is a snapshot of the past, and tells you little about the future. To find that view, you have to look at something far more ephemeral.

Thirty-one families may dominate the economy today, but that dominance is hardly indicative of an ongoing problem, merely a reflection of one we had in the past. The future could look like something else entirely.

As Per your request

permeation grouting