The largest edible oil producer in a country that has one of the highest per capita consumption of edible products announcing an Initial Public Offering (IPO) would normally be big news. In Pakistan, however, it must be taken with a grain of salt. Dalda has over the past few months been teasing an IPO on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX).

Back in January the company, which has been operational since before the formation of Pakistan, said it was looking to raise between Rs 3.3 billion to Rs 4.6 billion in a share sale. This would account for 15% of shares in Dalda and at Rs 4.6 billion could prove to be the largest ever IPO by a consumer staple company.

The only problem is that the news of Dalda looking for a massive injection of public money is not new. In fact, it has been in the works for more than six years. Dalda first expressed an interest in going for an IPO back in 2017. The company had announced they were looking to issue 8.25 crore shares via a book-building process at the floor price of Rs 85 per share.

Back in 2017 the company had stated they wanted the injection of money to expand their seed extraction plant and increase their seed crushing capacity by an additional 500 tonnes a day. In January, the company again announced it would go for an IPO with the same intention. According to Aziz Jindani, the CEO of Dalda, the company was looking towards expanding its Port Qasim facility, referring to the company’s factory at one of the country’s busiest shipping ports. The proceeds could more than double its capacity in Karachi to extract oil from seeds.

But then they delayed their January announcement again. Rumours were back about a Dalda IPO in March before dying out until now. So will Dalda finally do it or is this another moment of testing the waters and not taking the plunge?

The Dutch origins of Vanaspati Ghee

Our story starts in 1930 when a Dutch company called Dada, in association with Lever Brothers in London, now known as Unilever, collaborated to import cheap vanaspati ghee to the Indian subcontinent. Ghee had long been an ancient staple of the rich in the Indian subcontinent, used sparingly to make delicacies on festive occasions.

Traditionally, ghee is made from clarified cow milk, which is very expensive. Some European investors discovered a method to hydrogenate vegetable oil and turn it into a substance that convincingly mimicked the taste and function of ghee. Dada and Lever brothers, under the brand name Dalda, brought this new alternative called Vanaspati Ghee to the Indian market.

There is a long story as to how Dada and Lever Brothers came to an agreement to launch Vanaspati Ghee under the brand name ‘Dalda’ Ghee — and you can read more about it here. But when the first tins of this product hit the market, they made an impression because of the bright green palm tree logo on yellow that they used.

The vegetable oil being used to make Vanaspati Ghee came from the seeds of the palm tree. That is a legacy that we have inherited to this day. In Pakistan, the most commonly used edible oil is Vanaspati Ghee – significantly more so than cooking oil used by most upper class families in domestic cooking. All of this comes from palm tree oil. And it isn’t just Pakistan. Since the early 20th century, the oilseeds of the palm tree along with Soybeans have dominated global demand, with countries like Indonesia and Malaysia centering a large part of their economies around the production of these oilseeds.

In Pakistan, nearly 90% of the import of oilseeds is constituted by palm and soybean oilseeds. This places Dalda in a unique position and it makes sense why they would want to increase their oil pressing capacity. According to the SBP report, global consumption of oilseeds has increased manifold since the 1980s, with more than 600 million tons consumed in 2019. On the cooking oil end of the equation, Pakistan in particular is a country with a high-dependency, even compared to other countries with similar dietary preferences like Sri Lanka and India.

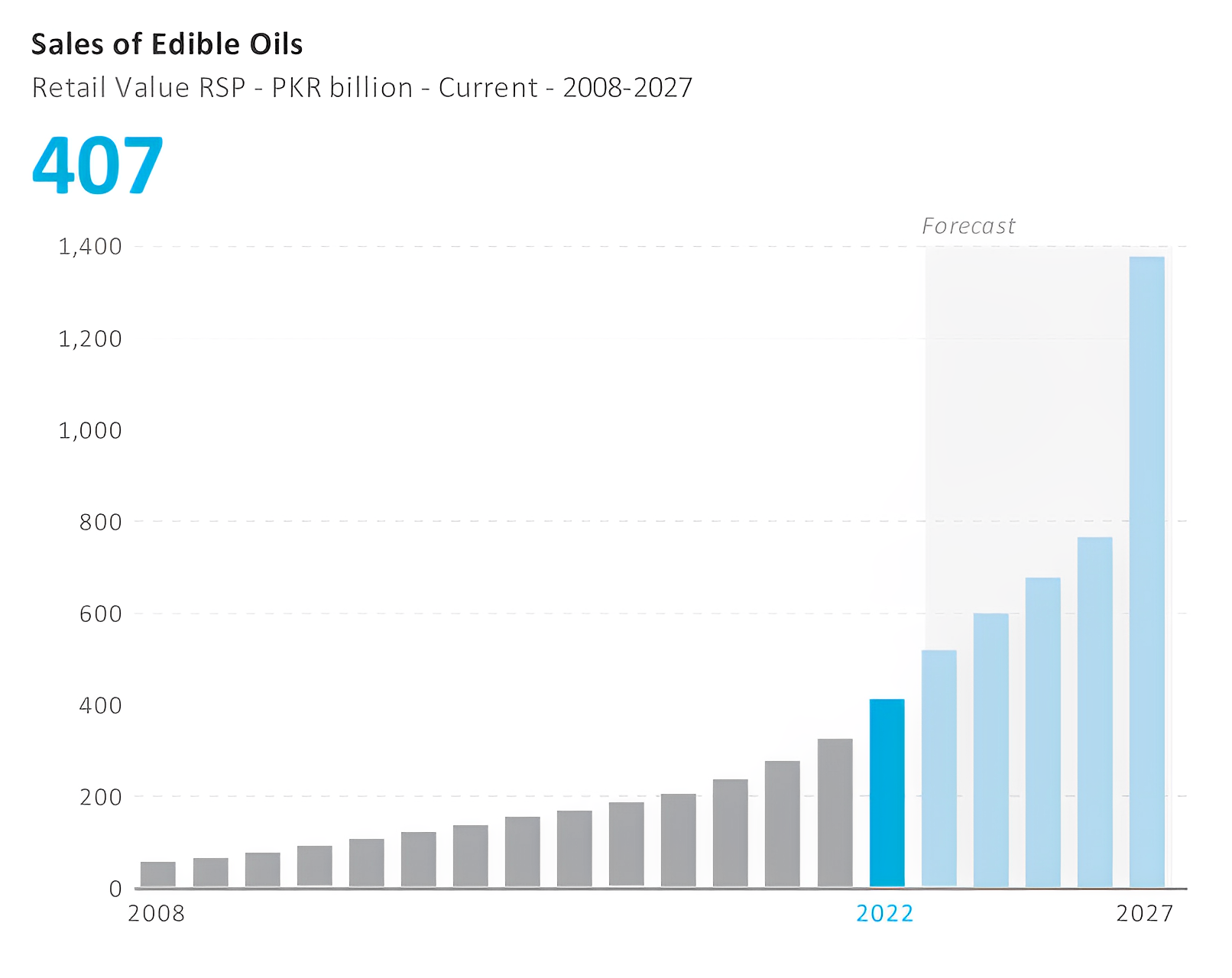

Edible oil consumption in Pakistan has increased significantly over the last few decades: from 0.7 to 4.7 million tonnes between 1981 and 2020. The main demand drivers are rising population, dietary preferences and increase in per capita income. According to the recent SBP report: Pakistan’s per capita edible oil consumption is already higher compared to economies with similar income levels. In addition, increasing income levels may also translate in increased per capita consumption of edible oil, as will population growth. According to the UN’s World Population Prospect 2019, at constant-fertility, the country’s population in 2025 is set to reach 245 million, and 328 million by 2040.

This implies that demand for edible oil will continue to increase noticeably. According to estimates by the Pakistan Oilseed Department, total demand for edible oil in the country is conservatively expected to grow to 5.9 million tonnes in 2025-26, from 4.7 million tonnes in FY21. As this demand increases the crushing and processing capacity must also increase. This is what Dalda wants to prepare for with their IPO and by increasing their oil pressing capacity.

Dalda’s expansion through the years

Unilever continued to own and operate Dalda in India and Pakistan after partition. Up until 2003, Dalda accounted for over 19% of Unilever’s revenues in Pakistan, when they decided to sell it. In 2003, Unilever decided to sell Dalda and the Westbury Group emerged as the successor of the company. Dalda saw immense growth under Westbury, which was quite well-known in Karachi’s trading and financial community, however, was not so well-known for being a manufacturing or consumer goods powerhouse. The company, run and owned by two Karachi-based brothers, Bashir Janmohammed and Rasheed Janmohammed, primarily operated as a commodities trading firm headquartered in Karachi.

While engaging in the trade of various commodities, their most significant focus was on palm oil, which serves as the primary raw material for vanaspati ghee production. In fact, at the time of the acquisition, Westbury held the position of being Pakistan’s largest importer of palm oil.

Despite being in the commodity business for decades and knowing it inside out, the brothers were not so familiar with the business of manufacturing and selling directly to the consumers. So, they retained the Unilever management team that had been running Dalda before the ownership had changed.

The post-acquisition growth included organic expansion, acquisitions, and diversification.

The first and most prominent expansion move that proved to be a successful venture happened in 2005, with the sale of Dalda’s products to the substantial expatriate Pakistani communities in the UK, Canada, and the US. Meeting the rigorous food quality standards of the European Union was a significant departure from their traditional Pakistani customer base, making this accomplishment a point of pride for Dalda’s management.

The following year, Dalda, in order to address an important market gap, introduced a new cooking oil brand called Manpasand. The management believed that Dalda primarily catered to the upper middle-class market and recognized the untapped potential in the middle-income segment.

The next phase of Dalda’s strategic, and needless to say substantial, growth occurred in 2007 through the acquisition of a controlling stake in Wazir Ali Industries. This was a struggling publicly listed edible oil manufacturer that owned the Tullo brand. This acquisition added another household brand to Dalda Foods’ portfolio. Then CEO, Perwais Khan has informed Profit that Tullo, which had faced difficulties, was successfully revitalised and had become one of the fastest-growing brands in the edible oils category.

In 2007, during a period of immense economic growth and the emergence of a substantial upper middle class, the newly emerged income group sought products beyond what Dalda currently offered. In response, Dalda Foods introduced Dalda Olive Oil, imported from Spain.

Beyond brand expansion, the company also made strategic investments to increase its manufacturing capacity. In 2011, they completed a new edible oil processing and seed crushing plant in Port Qasim, Karachi, increasing daily production by 300 tons. In 2012, a new edible oil neutralisation and bleaching plant with a 100-ton daily capacity was added. These enhancements improved the company’s ability to use locally sourced sunflower seeds instead of solely relying on imported oilseeds.

The initial eight years following the acquisition were marked by a whirlwind of efforts aimed at successfully expanding the business. From 2005 to 2012, Dalda Foods experienced an impressive annual revenue growth rate of 28.1%. This growth occurred despite an average inflation rate of 11.8% per year and resulted in the company’s revenue reaching Rs 22.6 billion by 2012.

Fast Forward to 2017, Dalda announced that it was going public, which did not happen due to “unfavourable market conditions,” according to their brokerage firm Arif Habib Corporation.

Finally walking the PSX ramp?

After striking one gold mine after the other, Dalda’s expansion spree came to a standstill for six odd years. Until early 2022, when the topic of the company potentially going for an IPO came up once again.

Summer 2023 was supposed to be a time when Dalda finally did a public offering. However, despite getting their financial accounts audited and approved by regulatory bodies, like the PSX and the SECP, Dalda did not go through with the IPO in June 2023.

Profit asked the underwriters of Dalda’s IPO at Arif Habib Corporation what caused this delay, in response to which they informed, “Pakistan was not part of the IMF program yet, which made it a bad time to go ahead with the IPO. The market conditions were still quite unfeasible. Now that the IMF bailout has been received, the market sentiment has also improved. The company is likely to go for an IPO after the audit of June 2023.”

However, it is still unclear as to when exactly one might be able to bid for a share in Dalda. Upon inquiry, Profit was told that “Dalda is conducting audits of their FY2023 accounts and also monitoring the market situation and will go for an IPO on the basis of FY23 audited accounts if the market is feasible.”

Well, the market has seemingly not been feasible for Dalda to do an IPO for the last six years. The 50 million shares that might be up for sale soon, are expected to be valued between 3.3 billion to 4.6 billion.

Dalda aims to raise capital for one main reason. Expansion of their oil refinery and seed crushing plant at Port Qasim. “IPO proceeds will be utilised towards expansion of existing business i.e. enhancement of seed crushing capacity from 400 tons per day to 900 tons per day,” Ammad Tahir, Director Investment Banking at Arif Habib Corporation enlightened Profit.

So, Dalda is essentially aiming to increase their plant’s capacity by 125%. According to analyst Waqas Ghani, the capacity utilisation of this plant was already at an optimum 79% in 2022. If Dalda successfully expands their capacity after the IPO, these numbers will increase exponentially.

According to Tahir, the demand for edible oil has been growing in the range of 2 to 3% in the past five years. The rise in demand can be attributed to the country’s increasing urbanisation and improving health consciousness among consumers. “The annual consumption of edible oil and fats is estimated to be around 4.5 million tons,” shared Tahir.

The anatomy of the giant

Let’s get one thing straight: Dalda is huge. Perhaps a bit too huge for its competitors’ liking.

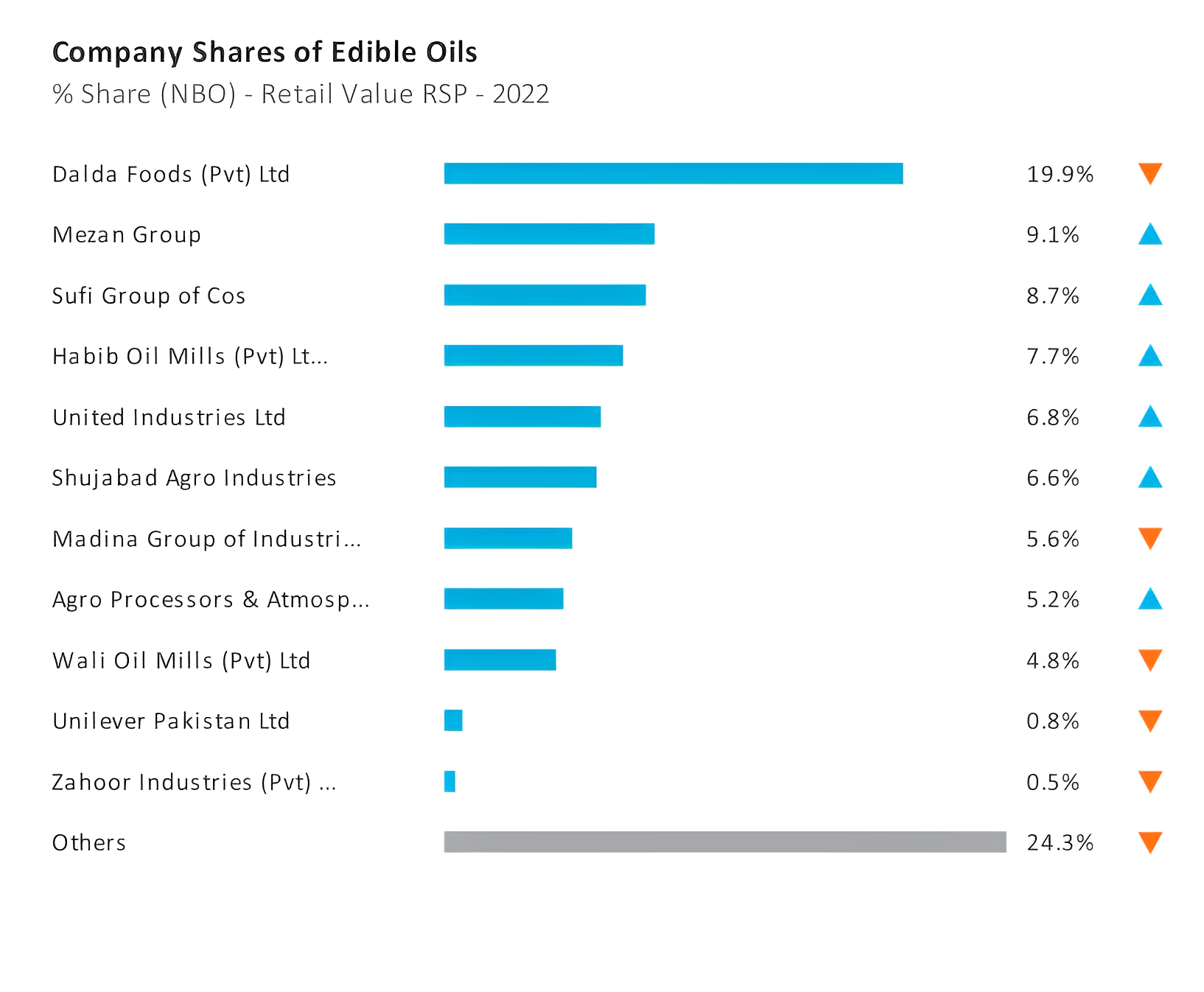

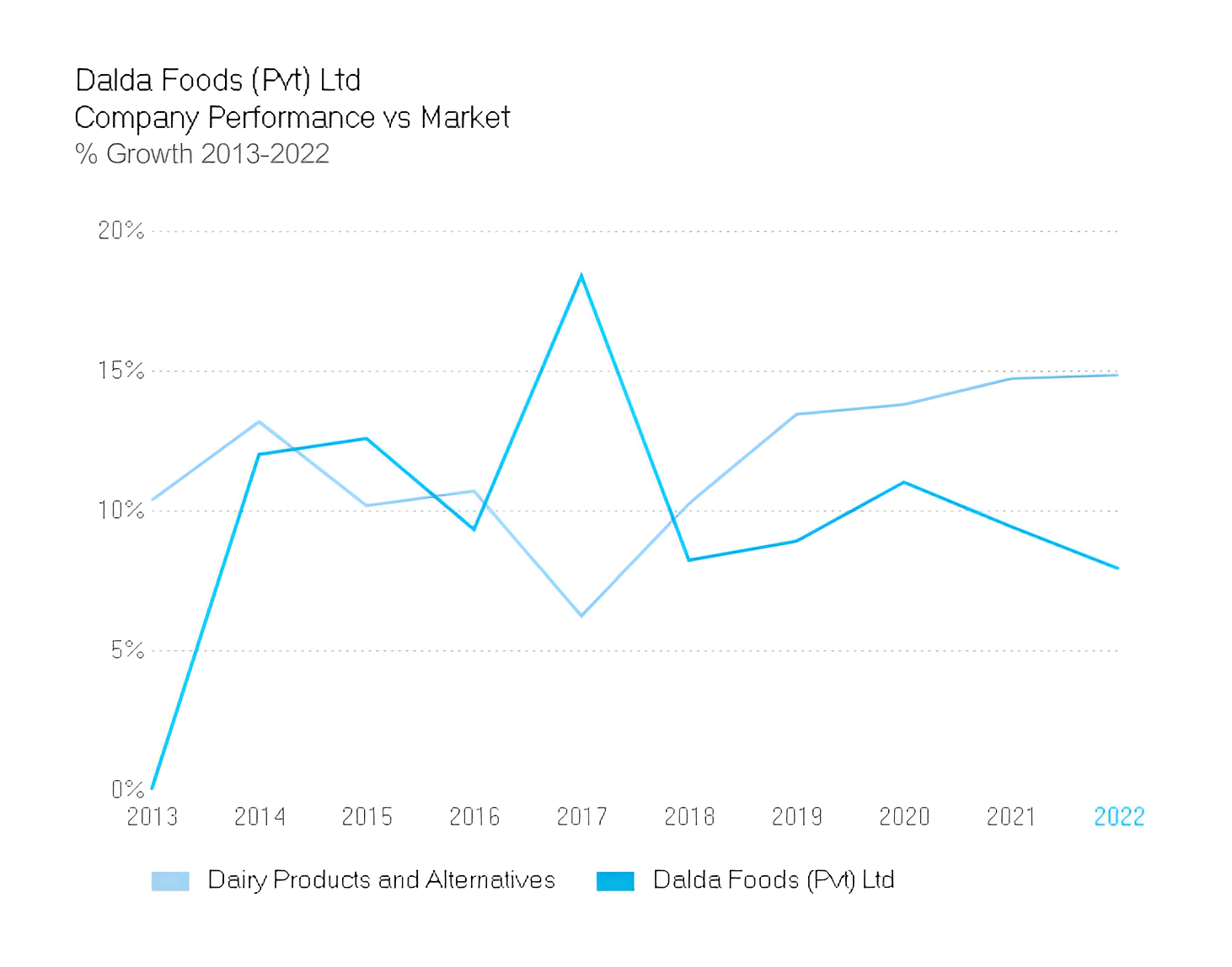

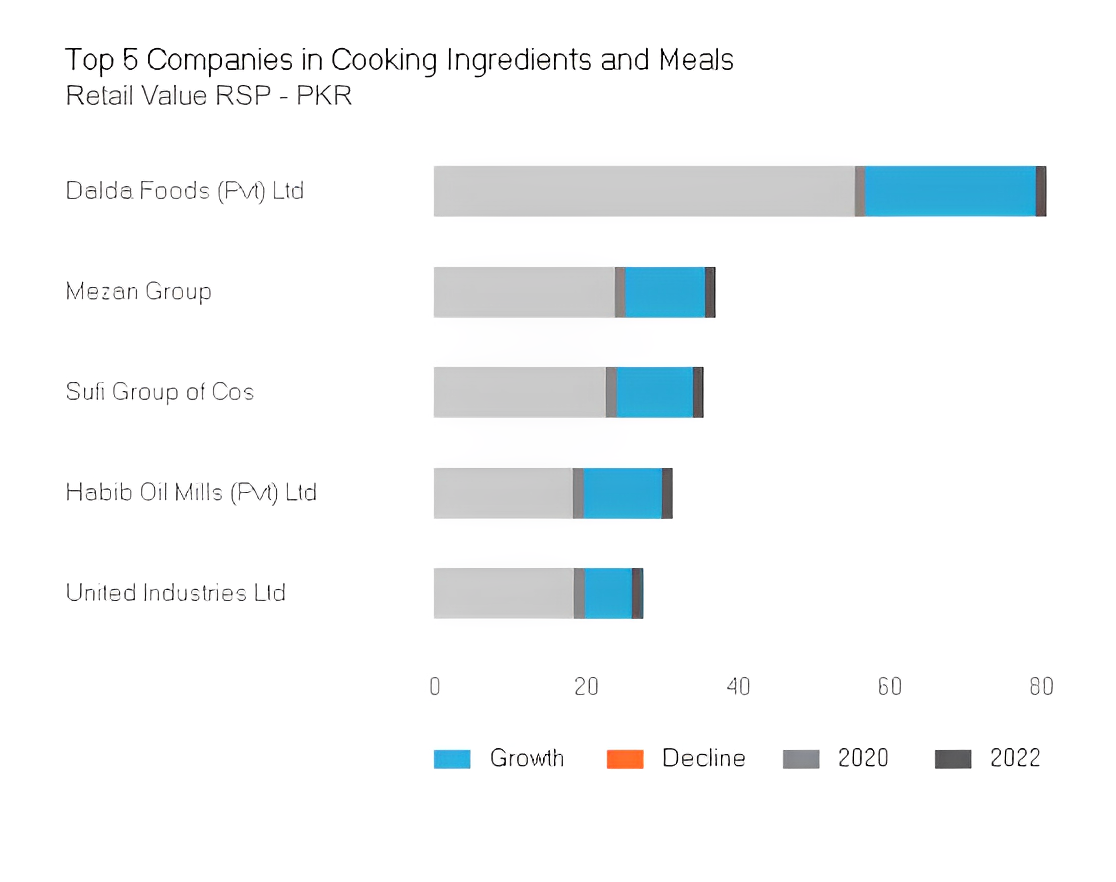

The present market division in Edible Oils between Dalda and its competitors is quite uneven, with Dalda taking up a considerable chunk of the pie already. According to reports released by Euromonitor, Dalda had a 19.9% retail value share in edible oil sales in 2022.

Now, you might be thinking that almost 20% is still not that big of a number. Well, think about it this way; the sheer size of the edible oils market was more than Rs 400 billion in terms of retail value in 2022.

Moreover, no other competitor including Mezan, Sufi and Habib has a market share of more than 10% in the edible oils and alternatives market.

Moreover, no other competitor including Mezan, Sufi and Habib has a market share of more than 10% in the edible oils and alternatives market.

Secondly, Dalda is also the third biggest company in the Dairy Products and Alternatives market after Nestle and Engro, with a 6.1% market share in the formal dairy (packaged milk and dairy products) category. It had a retail value of Rs 36 billion in dairy products, in 2022.

Thirdly, Dalda Foods Ltd is ranked at number 1 in the Cooking Ingredients and Meals category, with Rs 81 billion in sales at retail value and a market share of 18.4%.

Thirdly, Dalda Foods Ltd is ranked at number 1 in the Cooking Ingredients and Meals category, with Rs 81 billion in sales at retail value and a market share of 18.4%.

What happens when it gets even bigger?

What happens when it gets even bigger?

If Dalda’s IPO finally sees the light of day and turns out to be a successful one, its competition has another thing coming at them. Competitors have been unable to catch up with Dalda or its rapid growth while it is still a privately owned company.

And when we say competitors, we don’t just mean those in the edible oils market, but others like cooking ingredients and dairy products as we have mentioned above. Dalda has its hands in more pots of oil than what first comes to mind.

The IPO will not only help Dalda takeover a bigger share, perhaps even driving some competitors in the edible oil market out of the scene, but the company might also benefit in the several other markets that it operates in.

Considering that it already has a diverse set of operations and sectors within the food market, Dalda’s growth opens questions for the players in the other industries. What happens when Dalda has conquered more of the edible oil market? Will it use the extra resources, and perhaps greater revenues to compete in the other markets it already exists in?

best investment for long term . waiting for ipo

A well-researched, well-structured and insightful read!