Some phenomena in life are so ingrained in our minds that we take them for granted: the Earth’s roundness, the sun’s faithful journey from East to West. Likewise, in today’s Pakistan, it seems almost a self-evident fact that Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) is always on the verge of collapse. One could glance at any headline about PIA’s fortunes and be unable to tell which year of the past two decades it belongs to.

The story, from PIA’s glorious beginnings as an aviation pioneer that spawned a generation of companies to its current state of financial turmoil, has been regurgitated ad-nauseum. So much so that it’s perhaps a children’s tale at this point. It is also something that has become a quarterly tradition that floods our airwaves like clockwork when the company reveals its financial performance. However, this time the alarm bells are ringing a bit too loud to ignore.

In the past week, PIA has encountered one media calamity after another, reaching a zenith when the Government of Pakistan pronounced its verdict to jettison PIA and finally sell it off. The twist this time is that the Government is actually in dire need of cash, and might not have any tolerance for these losses anymore. The Government also has new regulatory instruments that could accelerate the sale if it so wishes.

The only hitch is, PIA contends it has finally overcome its obstacles and attained partial profitability again. It beseeches for some governmental assistance on debt resolution, vowing it could soar to new heights.

So, what’s going on?

A week of crises

Our story begins on Saturday, 9th September, when PIA announced on its X (formerly Twitter) account that it had secured the government’s approval for assistance with its debt. That tweet, however, mysteriously disappeared from PIA’s X account without a trace. No one knows when or why it vanished, but in retrospect it foreshadowed the events to come.

Fast forward to Monday, the 11th of September. The media was abuzz with the revelation that PIA had been compelled to ground its fleet due to a severe liquidity crunch threatening its operational viability for the ensuing months. Higher than usual flight cancellations evidenced the grounding of part of the national carrier’s fleet.

The subsequent day brought more disheartening news: PIA might possibly default on its payroll obligations for August as some of its bank accounts had been freezed.

As if on cue, on the next day, another revelation surfaced: an anonymous Director at the national flag carrier confided to a news outlet that the airline was on the brink of cessation and predicted its collapse by the 15th of September. The only glimmer of hope on the day was that it was reported that PIA’s accounts with the Federal Board of Revenue had been unfrozen, and it could subsequently process salary payments.

The icing on the cake came on the 14th of September. The Government declared it was injecting Rs 14 billion into PIA’s coffers but simultaneously announced plans to privatise the beleaguered airline. In fact, a new Federal Minister was inducted and tasked with privatising the company on his very first day.

This whirlwind of events, dear reader, transpired across a mere four-days. At the time of writing this piece, the 15th of September, PIA has not collapsed. So, what on earth happened?

“Amidst a tumultuous financial landscape, we were eagerly anticipating an influx of funds. Initially slated for the commencement of the week, an unforeseen delay served to amplify our existing predicaments,” elucidates Abdullah Khan, the Head of Marketing & Corporate Communications at PIA.

“Let me set the record straight — whispers of us halting operations on the 15th of September, or any time in the future, are nothing more than baseless rumours. PIA is a stalwart in the industry, firmly rooted in sound business principles. Should the storm continue to rage, our strategy involves a calculated reduction in operations,” Khan adds, dispelling any misconceptions.

“However,” Khan’s tone grows sombre, “the relentless onslaught of negative media speculation has sent shockwaves through our network of associated parties. It’s been akin to a snowball effect, with many succumbing to a pessimistic outlook.”

In an additional revelation to Profit, Khan categorically stated that no overseas aircrafts have been grounded. The cancelled flights were due to their ATR aeroplanes suddenly requiring unscheduled maintenance — a decision that was communicated well in advance, a full 10 days prior. And the anonymous Director who cried wolf? The Senate Committee on Aviation is hot on their trail.

So, is all well in the PIA camp? Not quite. PIA indeed needs to address their burgeoning debt issue — a fact they have openly acknowledged. The current situation is far from ideal, to put it mildly.

The (short-term) debt addiction

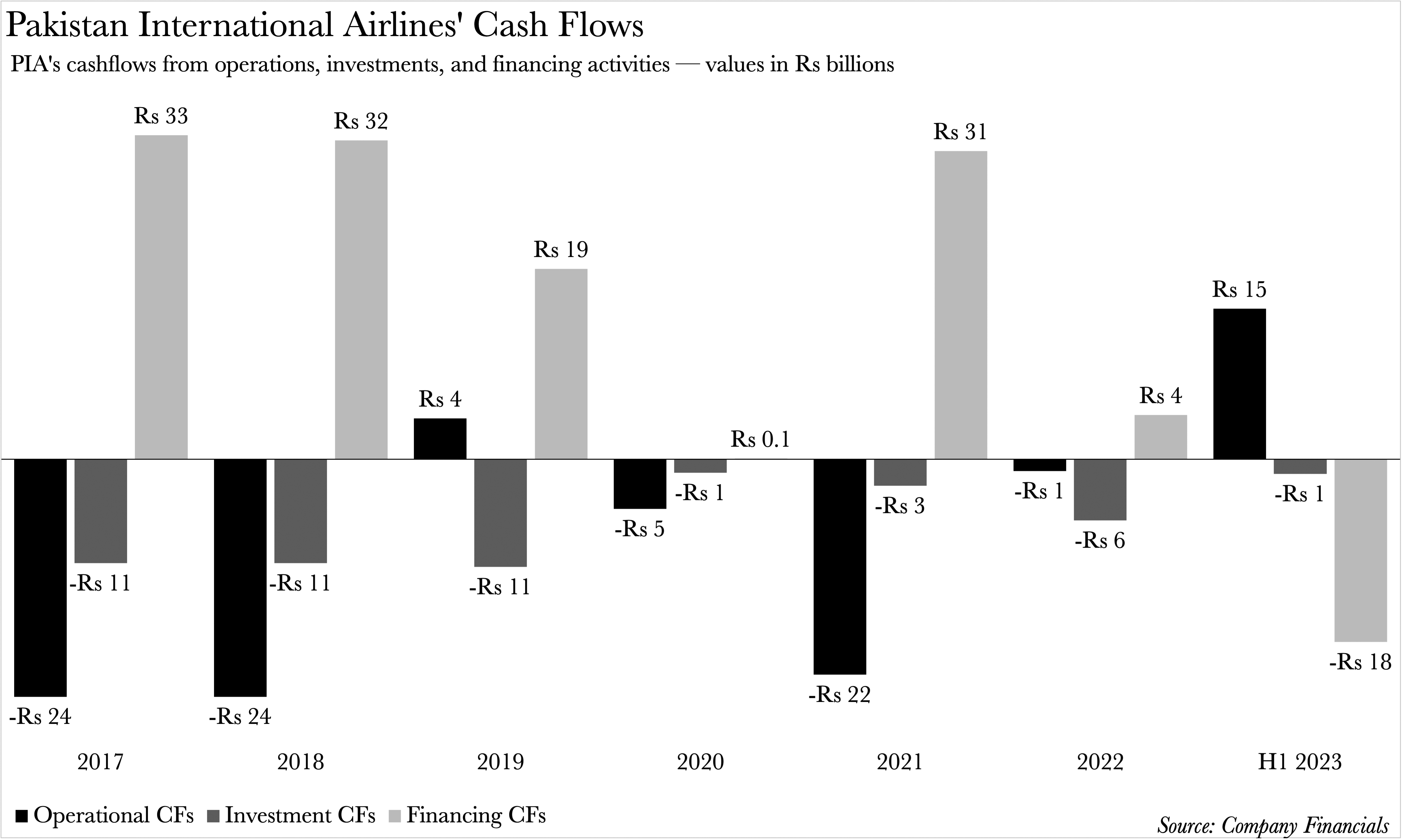

Let’s cut to the chase. PIA’s cash flows are in a state of chaos. A retrospective glance at PIA’s cash flows from 2017 to June 2023 paints a grim picture. PIA only managed to keep its head above water for a fleeting one and a half years. The remaining five years saw PIA grappling with negative cash flows from its operating activities. In layman’s terms, PIA was bleeding money from its core airline operations. So, how has it managed to stay afloat? The lifeline has been debt.

During the aforementioned period, it was only in the first six months of 2023 that PIA managed to repay more loans than it borrowed. That’s not to say it didn’t borrow. It did. This borrowing spree has been the lifeblood of its operations for the past six and a half years. Is this a sustainable model? Far from it.

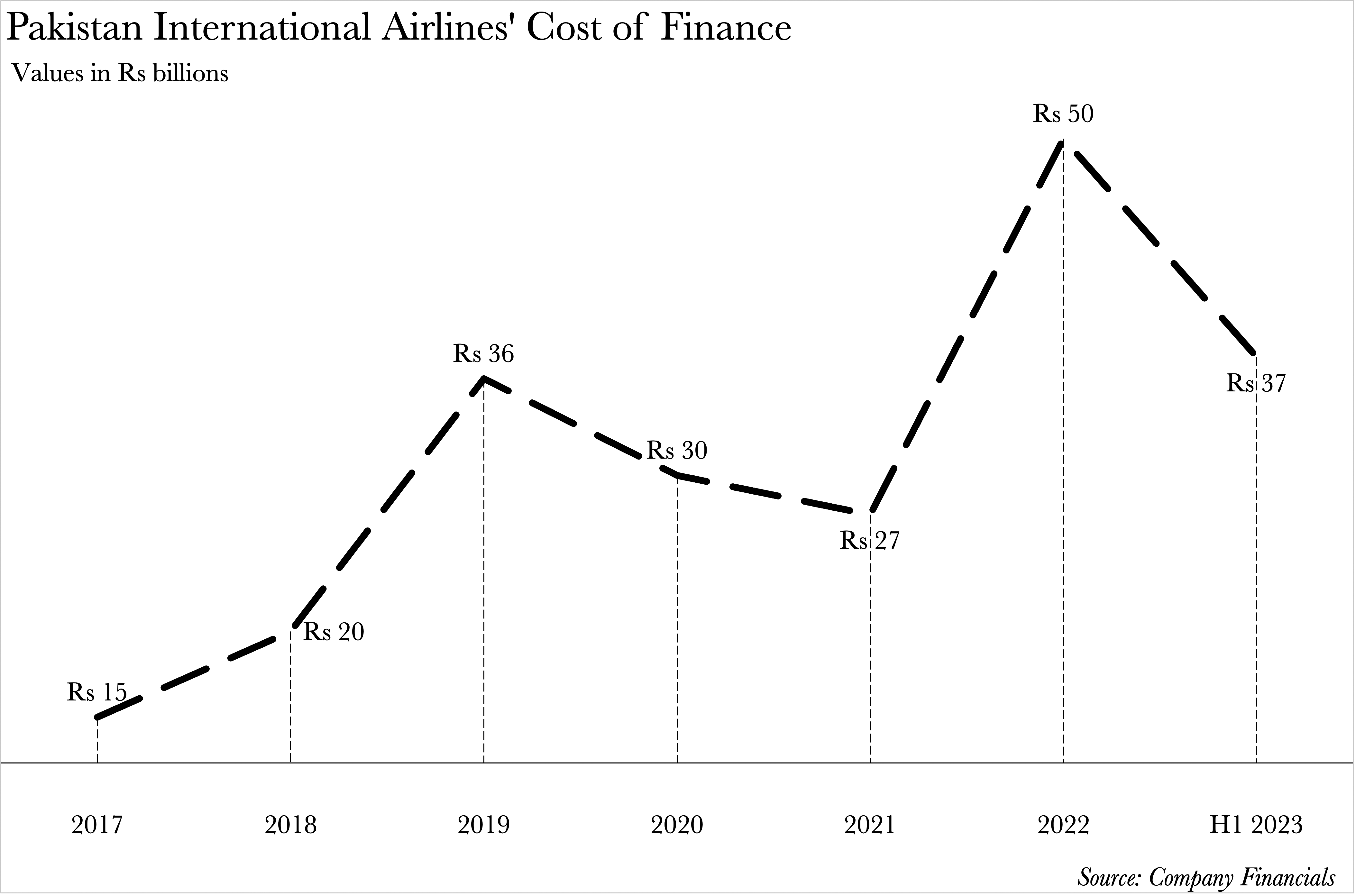

PIA’s finance costs for 2022 alone amounted to a staggering Rs 50 billion — a record high over the past six years. Yet, barely halfway into 2023, PIA has already incurred an alarming 74% of this cost. It is this escalating cost of finance that prompted PIA to engage the government in a dialogue for financial aid to alleviate its debt burden.

Read more: Can the Govt’s injection help PIA build on its gains in 2023?

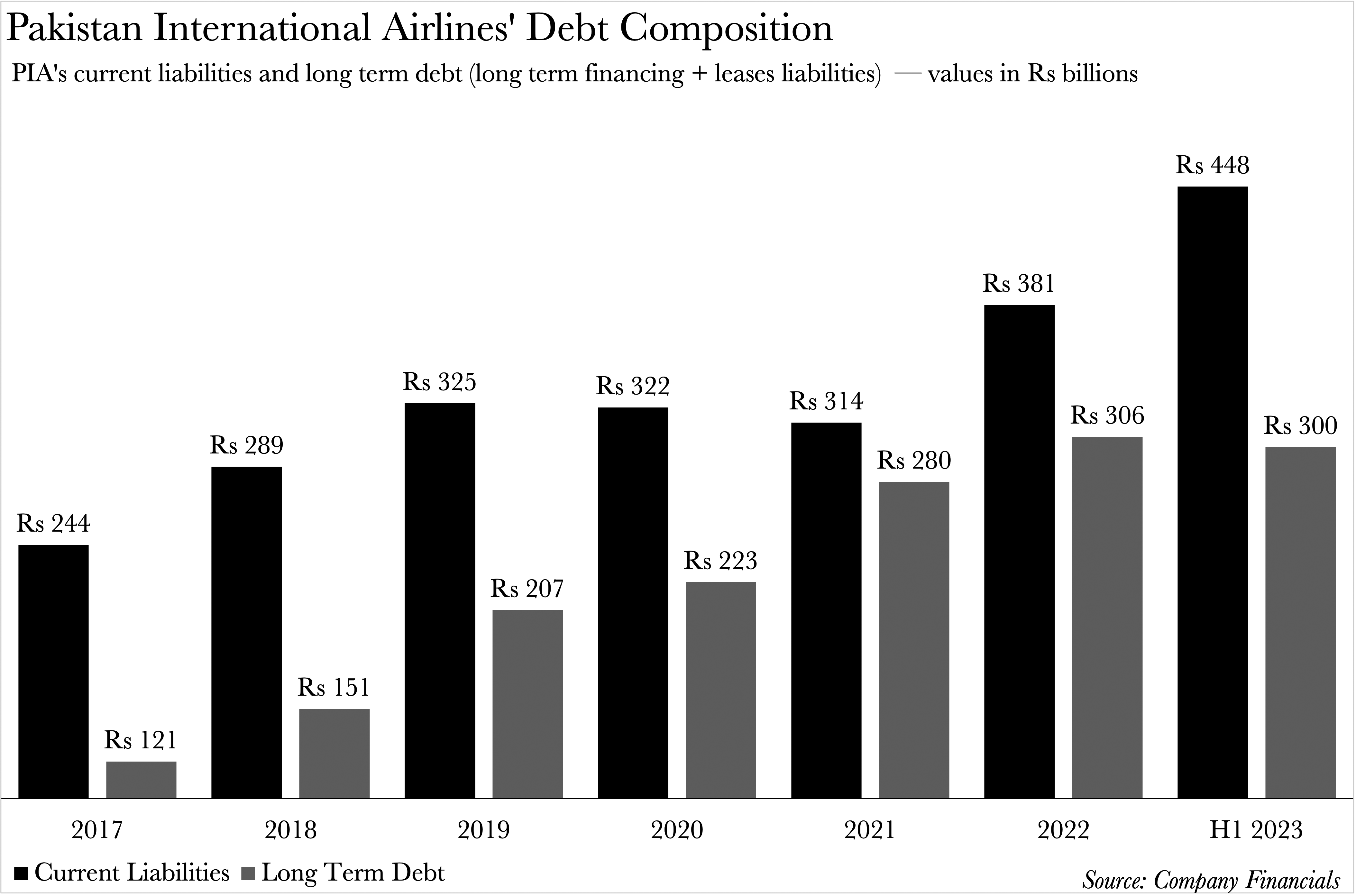

The most conspicuous reason for PIA’s soaring finance costs is perhaps the increase in the policy rate by the State Bank of Pakistan. However, PIA was bound to hit a wall eventually due to its precarious debt composition.

A closer look at it reveals a stark contrast between its short-term and long-term debt. The former has consistently outpaced the latter each year for the past six years.

If we factor in PIA’s advances from its subsidiaries and deferred liabilities (including pension obligations and vehicle redelivery expenses), its long-term liabilities do surpass its current liabilities. However, when it comes to the structure of PIA’s debt, short-term debt takes precedence over long-term debts. This is noteworthy because ideally, debt should not be structured in this manner.

The longer the maturity term of the debt, the lower the interest rate that is subsequently attached to it.

So, is PIA’s finance department manned by short term debt enthusiasts? Not really. Short term debt is the kind of debt that is most easily available to the company. Now that might sound odd upon a first read. Why are banks lending short-term debt to a company already crippled by it? Do the banks that PIA lends from not have any form of risk department whatsoever?

“All of PIA’s lenders have structured their debt against specific routes as security,” Yousuf Farooq, the Director of Research at Chase Securities. What does any of this mean? The revenues collected from these routes are essentially given to the lenders to repay the principal and interests in return for the funds they lend to PIA. The banks are all too comfortable with this method too.

“The lenders don’t have any problem in giving the debt because they know that they are going to get paid through PIA’s route revenue, which is essentially collateral. It’s a waterfall mechanism, but at the end of the day it doesn’t leave PIA with a lot of money,” Farooq continues. Can we then fault the banks for feeding PIA’s addiction? Yes. However, many don’t want to lend PIA long-term debt because they’re apprehensive about the company’s long-term future. This, Profit confirmed with one very senior banking professional. Very senior.

So, where does that leave us? Without pointing fingers, it’s just the tale of an organisation trying to do whatever it can to stay afloat in all honesty. The only problem is that it’s a public sector company, and therefore taxpayers are also paying the price.

Now, PIA is cognisant of all of this. They even have a proposal to fix the mess.

Living on a prayer

PIA’s contention, a point elaborated upon in our aforementioned article, is that a restructuring or assistance with its debt could be the lifeline that allows the company to turn a profit. It highlights the stark contrast between its operating profit and net profit in its performance for the first six months of 2023. The company outlines how it turned an operating profit, but was unable to capitalise on its gains due to its cost of finance, and subsequently reported a final (net) loss.

There is merit to PIA’s argument. Its heightened cost of borrowing is due to its debt composition. However, this presents PIA with a potential silver lining. The more funds it can allocate towards reducing its short-term debt — currently standing at Rs 448 billion — the more it stands to gain from reductions in borrowing costs.

There’s no denying that PIA has achieved the unthinkable by managing to turn an operating profit. Whether PIA can sustain its winning streak for the remainder of the year remains a mystery. However, there is potential upside to PIA going forward into the remainder of the year. The flag carrier has made progress on regaining access to its routes in the western hemisphere, which are also some of its most lucrative.

If we were to take an even more macro perspective then we could point to the International Air Transport Association’s (IATA) consultancy business plan 2022-26 for the flag carrier. The plan, touted by IATA, could transform the flag carrier into a profitable entity by 2026.

However, not everyone shares PIA’s optimism about its turnaround strategy.

“PIA is an important national asset, however it has been unprofitable for years. Owing to the lack of fiscal space, it has become important that it is given to the private sector, be recapitalized through private funds and revived,” declares Nadia Ishtiaq, Managing Director (Corporate Finance) at KTrade.

Ishtiaq further elucidates, “Debt is no longer a viable option to optimise operations or cash flows.”

Now, the Government seems to be thinking along the same lines as Ishtiaq. At least based on their most recent stance regarding PIA. However, as many times as we’ve all heard about PIA’s financial woes, we’ve also heard about how it was going to be privatised. As it stands, based on historical precedence at least, it seems doubtful the government will pull through with the decision to privatise PIA.

But let’s assume, for argument’s sake, such a deal, however unlikely, was near fruition; what would it look like?

What a new PIA would look like

In the realm of PIA’s potential transformation, two primary transaction models emerge as contenders: the division into ‘good company/bad company’, and the bifurcation into an Operating Company (OpCo) and a Property Company (PropCo). It is unequivocal that PIA must undergo a metamorphosis, for its survival as a singular private entity seems financially unfeasible.

Let’s start with the ‘good company/bad company’ model.

“Envision extracting the aircraft, the profitable routes, the operations yielding revenue, the skilled workforce, and all other profit centres, and amalgamating them into a single entity,” elucidates Asad Ali Shah, a former Country Managing Partner at Deloitte. “The remaining liabilities, surplus staff, and all other loss centres are then relegated to a separate entity,” Shah adds.

The fate of these two entities? The ‘good company’, now streamlined and profitable, is primed for privatisation, while the ‘bad company’ remains under governmental purview for future strategising. The government stands to gain through taxation and reduced losses from the ‘good company’, while simultaneously devising debt management strategies and severance packages for redundant staff. A similar strategy was successfully employed during K-Electric’s privatisation.

The key objective with this arrangement, as Shah highlights, is to extract the good PIA that can create value and future cash flows from the huge liabilities that have been incurred and have to be owned by the government. The idea is to reduce the burn rate and generate some cash flows from good assets that can be used to pay the liabilities (the bad PIA part).

Turning our attention to the OpCo/PropCo model, we see another approach. “The government would need to carve out the core airline operations and ancillary businesses such as properties, hotels, etc,” elucidates Ishtiaq. The reason for the specific split is that PIA owns a lot of properties globally, these properties are consolidated into the PropCo, whilst its core operations are kept as part of the OpCo.

“The real estate can be leased out separately at a later stage to ensure maximisation of proceeds to the Government,” Ishtiaq adds. Whether or not these in particular are made private is up to the government. PIA’s core business, the OpCo is then the one that is privatised.

Ishtiaq also highlights a “pay as you earn” model, albeit one that has yet to be implemented in Pakistan’s privatisation schemes. Despite its existence among a plethora of other models, it is anticipated that the government will likely opt for one of the two aforementioned models should they proceed with privatisation.

Now that we know what a future PIA might look like, the question that inevitably arises in every mind is — why would anyone desire it? Moreover, the conundrum persists — could one possibly trade it for its fair value, especially when potential buyers are acutely aware of your desperation?

Running out of time for humpty dumpty

PIA is a negative equity company. Negative shareholder equity is a chilling scenario where a company’s liabilities to its investors eclipse the worth of its assets. In layman’s terms, when a company’s mountain of debt towers over the aggregate value of its assets, even after a complete liquidation, it is branded with the ominous label of negative equity.

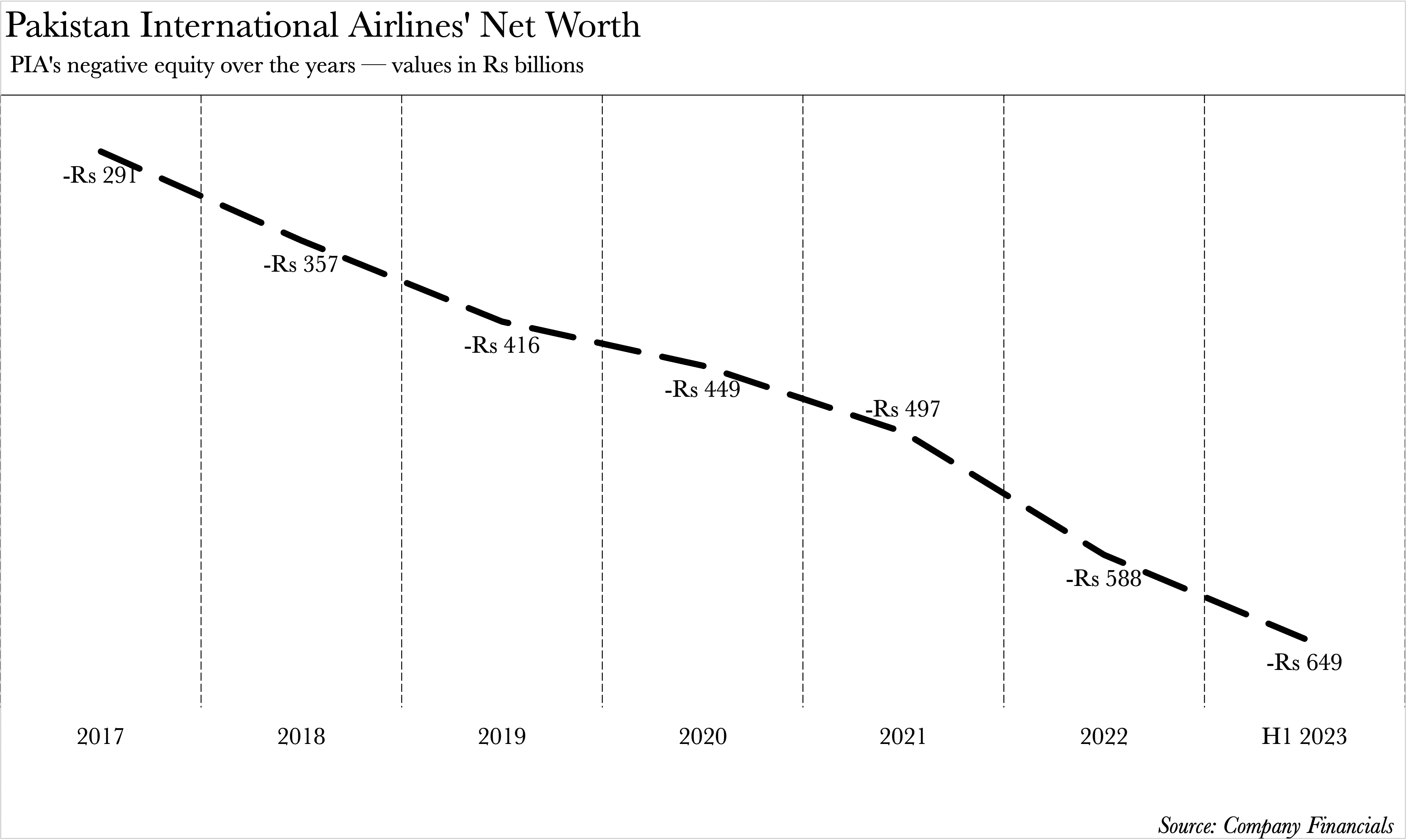

The fiscal abyss that PIA finds itself in has only yawned wider with time. The negative equity has mushroomed from Rs 291 billion in 2017 to an astronomical Rs 649 billion in June 2023. This gargantuan sum also symbolises the debt albatross that any prospective buyer would be saddled with upon acquiring PIA.

Does it make sense for anyone to want to buy it? Surprisingly, yes. Shah explains with an air of optimism, “PIA unfurls an unparalleled opportunity for any ambitious newcomer yearning to penetrate Pakistan’s airspace, or an incumbent aiming to fortify their position. While the buyer would need to brace for the depreciation of the rupee earnings, they stand to reap rich rewards from the dollar-denominated earnings accrued from Pakistanis embarking on overseas journeys. Moreover, they would not only carve out a niche in the country but also tap into the vast and untapped reservoir of the diaspora,” Shah elaborates with a glint of hope.

And what about the elusive fair value? “As far as the privatisation process is concerned, it is very transparent,” begins Ishtiaq. She continues, “independent financial advisory teams are engaged through a competitive process. Which then conducts detailed due diligence to arrive at a fair value, identify transaction roadblocks and suggest any changes that are required to optimise the privatisation proceeds .”

“A successful bidder is selected based on the highest bid, through a well defined transparent process,” Ishtiaq adds. A reference price for the bids is normally calculated based on factors such as net asset value, future cash flows, and potential dividend streams. Farooq highlights how in PIA’s case, it will likely hinge solely on the net asset value.

However, it’s plausible that PIA will change hands at a bargain price — a scenario that isn’t without precedent. “Pakistan is perpetually shackled by financial strain. We procure loans (especially foreign currency external debt) at high interest rates to finance our unproductive expenditure, resulting in a mountain of unsustainable public debt. Investors seeking equity will demand significantly higher than average dollar returns due to the heightened risk of continuing rupee devaluation associated with our country. This doesn’t imply that our business operations should grind to a halt, ” Shah adds with a note of defiance.

In all likelihood, PIA will be sold at a discount unless the Government can miraculously make it profitable before divesting it. If that were feasible, privatisation wouldn’t have been mooted in the first place. While PIA does have a blueprint to potentially extricate itself from this quagmire, the Government appears sceptical. Simultaneously, if the Government harbours doubts about PIA’s viability, it would need to dangle enticing carrots before potential buyers. What do these incentives typically entail? Imagine selling a product priced at Rs 100 for Rs 70 to ensure completion of the transaction and asking the buyer to address any issues that rear their heads subsequently. What you get as the final amount after your carrots hinge on the base value — and PIA’s base value currently languishes at negative Rs 649 billion.

One certainty amidst all this uncertainty is that indecision carries a hefty price tag. If the rupee plummets further or if policy rates soar, exchange losses and already exorbitant finance costs will spiral out of control. The government must either place unwavering faith in PIA and fix it, or sell it outright without further ado.

While opinions may be polarised on whether privatisation should occur or not, there seems to be consensus that maintaining the current fiscal position is untenable, much to the detriment of the economy, but more importantly the taxpayer.

With Rs649 B negative equity It will be a dream to sell it off even at a Big Re.00000. Naturally GOV has to take up the loans adding to its existing infinite numbers of loans.. Lets face it .

If a Company is bleeding on average Rs. 50 billion or more just to keep 10000-14000 employed… at the cost which can feed 138,889 people with minimum wages of Rs.30,000 (50billion/30000/12) per month for the whole year… let those 10-14K be unemployed and feed the 139K for free.

and BTW that 139K means (139K*2)(family of 2) 277,778 no.s of people. now please don’t argue that 30K cant feed 2 people a month.. obviously that can’t. it is based on minimum wages set by govt itself.

Thank you for providing such valuable information in your post. In certain cities in Pakistan, the driving regulations are quite stringent wether it is for air or by road. Safety holds paramount importance, particularly when navigating the roads of Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. To ensure your safety and mitigate various potential risks, it is highly advisable to consistently adhere to the established driving rules and regulations.

Select exquisite products from our wonderful collection of amazing products and enhance your shopping experience. Here is a bundle of creative items available, so click these items and purchase them.

Pia needs a proper and honest management even then will years to break even