It was a big week for urology in Pakistan but in a decidedly bittersweet manner. On the one hand there was the news that the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT) was interested in buying the Regent Plaza — a sprawling five star hotel near the Jinnah International Hotel in Karachi. The proposed acquisition of the hotel could be worth nearly Rs 4 billion, indicating the success that the SIUT has had not just as a dedicated, philanthropic, patient care facility but also as a financially savvy charitable organisation.

In a country with abysmal medical outcomes and crumbling healthcare infrastructure, SIUT is a miracle. But the dizzying high of its sustained success was short-lived with the news that the government of Punjab had busted a gang trafficking kidneys to wealthy foreign clients. The initial police reports suggest that the gang was led by a single doctor, Fawad Mumtaz, who, assisted by a car mechanic as an anesthesiologist, has admitted to conducting 328 illegal kidney transplants in Pakistan.

What makes the situation worse is that this is the sixth time Mumtaz has been arrested. His practice as Punjab’s top-most illegal kidney operation doctor has been well-documented since at least 2009. Every time his arrest has been followed by release thanks to the many political and bureaucratic connections he has made over these years through his lucrative business.

The kidney trade has plagued Pakistan for many years now. In fact, up until at least 2017, Pakistan was perhaps the largest hub of illegal kidney transplants in the world. Within the country Punjab was the hotspot for such procedures. One of the reasons for this has in fact been that the presence of SIUT in Sindh has seen a significant decline in kidneys for sale.

The question is, can SIUT be copied elsewhere in the country? As a charitable organisation the institute has provided care and treatment to countless people and has become a standard bearer in the healthcare industry. But how much of this success is practically replicable, particularly in a country whose healthcare system is struggling with problems as basic as illegal kidney transplants? Profit investigates.

The SIUT story

The story of SIUT is synonymous with the life of Dr Adib Rizvi. Nine years old at the time of partition, Dr Rizvi moved to Karachi with his family from Jaipur. This is where he got his initial education. As part of the first generation of Pakistanis, Dr Rizvi was one of the many young doctors, lawyers, civil servants, soldiers, farmers, businessmen, and political leaders that were native to Pakistan. Their efforts were to determine the course the fledgling nation would inevitably chart.

As a medical student in the late 1950s at Dow Medical College in Karachi, Rizvi’s batch was one of the first in the country to be trained in the use of penicillin. Clearly this was a time of great change for medicine and with the expansion of medical philosophy opportunities in medicine were opening up. Many Pakistani doctors were going to the United Kingdom in particular to pursue services in the National Health Service (NHS).

This is the route that Dr Rizvi took after graduating in 1961. At the UK’s NHS, he undertook a fellowship in surgery for much of the decade. This is where he developed his early vision for what healthcare, in particular public healthcare, should look like. As a taxpayer funded healthcare system the NHS has often served as a n example of what government provided healthcare facilities should look like.

Which is why when Dr Rizvi returned to Pakistan at the end of his fellowship in 1970, he gravitated towards the public sector. “I began to think that healthcare should be the basic right of every human being—a birthright, like education,” he was quoted by the British Medical Journal as saying.

In 1971 Rizvi, by then an assistant professor of urology, took over the eight bed genitourinary ward at Karachi’s Civil Hospital. At the time the government was spending around 0.7% of the country’s gross domestic product on healthcare. In 1973, Dr Rizvi met Anwar Naqvi. Both were serving at a medical relief camp set up for victims of that year’s devastating floods. Soon Naqvi had joined Rizvi at Karachi’s Civil Hospital and the two began curating an established team that continues to work with him. Over the next five decades Pakistan’s population grew from 70 million to 185 million, the country underwent two military coups, two massive earthquakes, the war on terror, and then finally the country’s first democratic transfer of power. Negligence in healthcare remained constant through all of this.

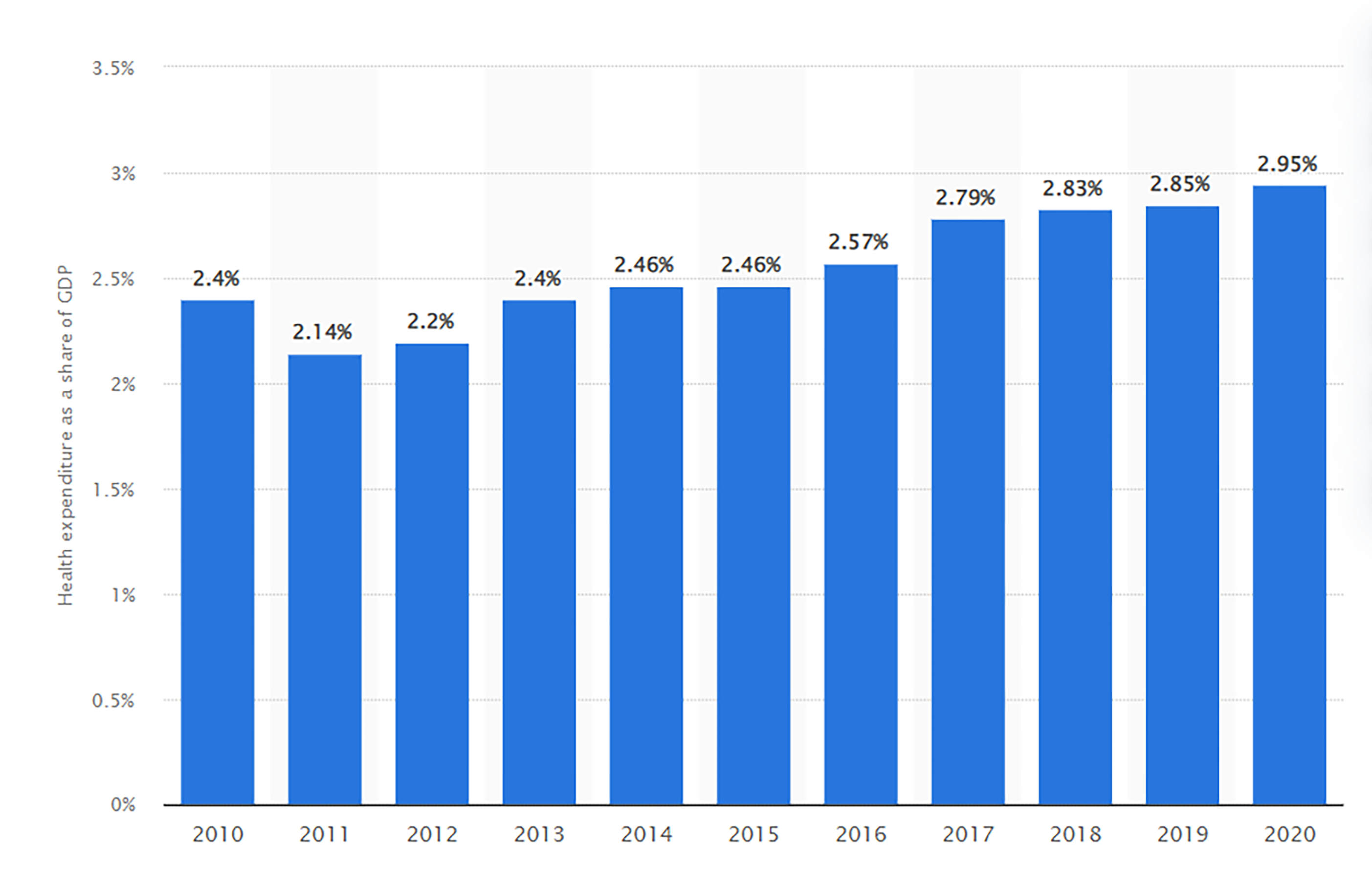

Government spending on healthcare currently is dangerously low, and between 2010-2023 has hovered between 2.4% to 2.9% of the country’s gross domestic product. This is far less than what is required in a country facing the kind of problems Pakistan is facing. These include, in no particular order, some of the highest rates of maternal, foetal, and child mortality in the world; a shortfall of around 200 000 healthcare workers; and the stubborn persistence of polio (only Pakistan and Afghanistan remain endemic for the disease).

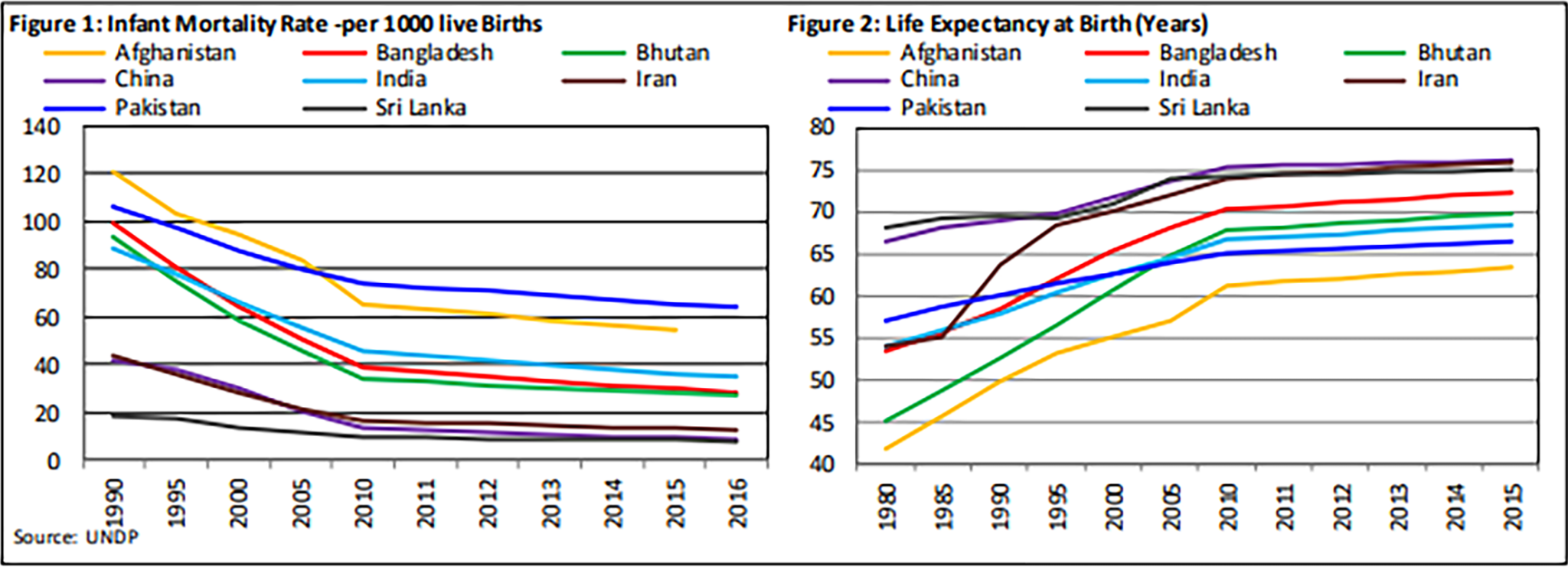

More specifically speaking, this means that 46 babies died before the end of their first month for every 1000 babies born in Pakistan making it the most risky country for newborns, ahead of even sub Saharan African countries and Afghanistan.

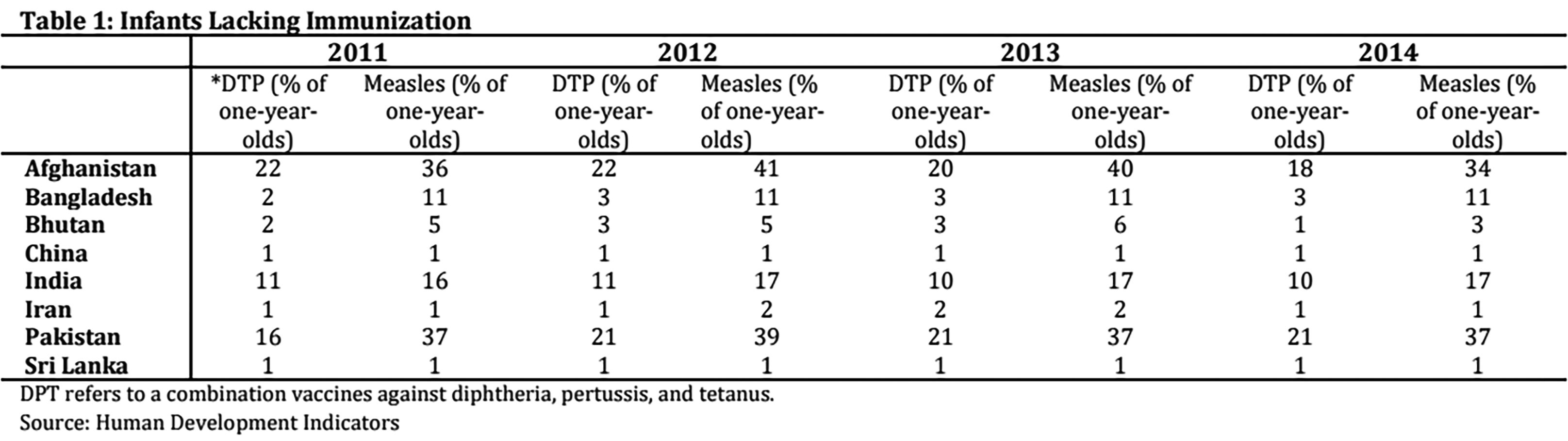

In reference to Immunization Indicators, Pakistan is being recognized as one of the few remaining countries with widespread polio. In terms of Infants Lacking Immunisation, the status of Pakistan is quite alarming given the effects of infectious diseases on economic growth in literature. Number of infants lacking basic immunisation is not only far below than other regional countries but also deteriorated over the years.

According to a more recent report by the journal Scientific Report, 44% of children less than five years in Pakistan were found stunted. Close to 31% were found underweight and 15% were found wasted. In addition, according to the National Nutrition Survey (2018) of Pakistan, 40% of children under five years of age were found stunted, 17.7% were wasted and nearly one-third of children were reported underweight (28.9%).

The earlier mentioned report of the SBP points out that the unsatisfactory performance for most of the targets may be attributed to suboptimal allocation of budget by government to health sector, internal and external economic and non-economic challenges. As a result of these terrible health statistics, Pakistanis are more susceptible to disease than the citizens of other countries. On the urology front alone, according to a report of the British Medical Journal, around 25 000 Pakistanis have renal failure every year. About 10% of these patients can obtain dialysis, a session of which costs $20-25 in the private sector, and less than 5% can obtain a kidney transplant, the cost of which ranges from $6000-10 000. Specialists are in short supply. Pakistan has no more than a few dozen nephrologists and even fewer transplant surgeons.

It was with these constraints that Dr Rizvi launched his mission. His argument was that the government was severely exhausted and unable to cope with a country the size of Pakistan. Remember, this was also well before 2008 so Pakistan’s ‘democracy’ was far from developed and devolution was a distant concept. From his experience in the UK Dr Rizvi argued that healthcare should be a partnership between the public and the government.

“We have to create a partnership between the community and the government,” he explained. The Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, which grew out of the eight bed ward, is such a partnership.

The SIUT was born as an eight-bed surgery ward in Karachi’s Civil Hospital in 1972. The confidence of the administration and the people that Dr Adib Rizvi won by his zeal for the methodical care of indigent patients facilitated the small unit’s recognition as the Department of Urology and Transplantation in 1986. Five years later, it became an autonomous institution under a Sindh act and became functional as the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT) in 1992.

This was perhaps one of the biggest decisions that Rizvi could have made in regards to what direction SIUT would take. As the leading light of the institution Dr Rizvi was also the person interacting with most donors and his credibility was a huge pull when it came to the hospital’s funding. But instead of opting to create a private charitable hospital, he sought to develop instead a government health facility’s capacity for delivering up-to-date medical care to the people, especially the poorest among them, without any cost to them and without compromising their dignity. In the words of the late I A Rehman, “this approach reinforced the principle of the state’s obligation to respect the citizens’ right to health. At the same time, it demonstrated a public health facility’s capacity to deliver if it had the right people to run it and if political authority was not blind altogether.”

The institute now takes care of nearly a million patients per year, and specialises in providing emergency services, major and minor surgical procedures, lithotripsy and dialysis sessions, transplants, radiology tests and laboratory investigations by extraordinarily skilled professionals. Since 1985 surgeons at SIUT have performed almost 5000 kidney transplants, including Pakistan’s first cadaveric and paediatric transplants. The institute has treated around 10 million patients since its inception. Several satellite branches are dotted around Sindh. There are also advanced plans for a dedicated paediatric urology, nephrology, and cardiology unit that will be named after Philip Ransley, a paediatric urologist from Great Ormond Street Hospital who has often visited the institute to teach and perform complex reconstructive surgeries.

A question of funding

Now all of this is well and good. The SUIT is an incredible organisation with an inspiring story that should be emulated in other regions of the country. The only problem is where will the money come from and who will lead the efforts?

A glance at some of the largest healthcare related charities in Pakistan will reveal that each has a dynamic, dedicated, and charismatic leader. For decades Abdul Sattar Edhi along with his wife Bilquis Edhi ran the Edhi foundation — one of the largest ambulance networks in the world. Part of the reliability of the foundation was Edhi’s own spartan way of life and rejection of luxury. His personal honesty made him trustworthy and thus the darling of not just large but more particularly small, everyday donors. Similarly, Imran Khan played and won a world cup on the back of the dream of building Shaukat Khanum. In what proved to be his second innings in life Khan successfully fundraised and made the hospital a reality with two more chapters in Karachi and Peshawar. While his fundraising with the general public was less successful than Edhi but his big personality made him a popular figure amongst the elite where he gained some of his bigger donations.

In both cases there is a solitary leader that embodies the organisation. Dr Adib Rizvi and SIUT fall somewhere in between these two philosophies of philanthropy. While he is a well known figure, particularly in recent years with his distinctive white hair and heavy-set glasses, he is by no means a celebrity in the same way that Abdul Sattar Edhi was or Imran Khan is. One can neither imagine Dr Rizvi lifting a world cup trophy nor being the subject of an iconic photograph sitting in a white Suzuki Bolan the way Edhi was. Instead, Dr Rizbi relies on a mix of popular support for SIUT and big donor funding particularly from overseas Pakistanis. He is also media shy, and upon Profit’s inquiry for an interview, this correspondent was very politely told that the good doctor does not give interviews but all of his views and statements were readily available on the internet and shared promptly by his team. He is by all accounts a figure more suited to medicine rather than fundraising but has had to become good at the latter.

So where is the money coming from exactly? For starters the organisation is a public hospital. SIUT’s 750 bed facility in Karachi is provided by the government of Sindh and as such the hospital has many of its operational costs subsidised. In this way the SIUT receives around half of its funding from the government. This in itself solves a major problem which is a glittering example not just for Pakistan but all of South Asia. It is difficult to speak of surgery in this region of the world with any great pride. The rate of surgery, meaning how many patients get operated upon, in rural Pakistan is 124 out of every one lakh patients according to a different study of the British Medical Journal. In comparison, the rate of surgery in rural towns in the United States is 8345 patients out of one lakh. The same study, which is from 2004 and is somehow still the latest data available on this, points out how even back then “SIUT in Karachi is an example that can be emulated. It conducts 110 renal surgeries a year with internationally comparable results.”

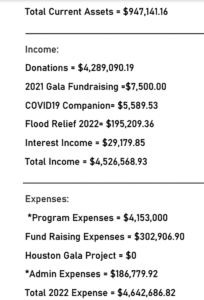

While the government of Sindh does contribute in this way to the funding of SIUT, much of its donations come from either the general public or SIUT North America — a charitable organisation formed in the United States in the year 2000 meant to be the main donor for SIUT in Pakistan. Most large donors send their donations to SIUT through SIUT North America. A look at SIUT North America’s annual report for 2022 shows that in 2022 alone they raised over $4.5 million for SIUT Karachi through campaigns for Sadqah, Zakat, Flood relief, and Covid-19 relief. And these were just the cash donations. SIUT has prided itself on maintaining the latest technology in its facilities. Since 2019, SIUT North America has donated equipment and technology to the tune of $15 million.

“Medicine is dynamic, and technology is changing rapidly; to survive as an institution, you have to keep pace with new modalities and breakthroughs,” said Dr Rizvi in an earlier statement. “We started with urology, we added nephrology, transplantation, radiology, an oncology department, and a bioethics unit—we continue investing. This model can very well be replicated. There are really only three conditions. You have to be committed because the facility must run day and night; every effort should be made to be on the cutting edge of technology; and you should be transparent and accountable to the government and the community at large”.

What is perhaps the most impressive in this is that SIUT spends most of the money it makes on patient care and a significantly smaller portion on administrative expenses. Of the $4.5 million raised in 2022, SIUT spent $4.15 million on program expenses. Only $187,000 were spent on administrative expenses. Of these expenses too, salaries and wages only accounted for around $131,473. This, of course, is the data available for the publicly listed SIUT North America and not the doctors, nurses, healthcare workers and administrators working at SIUT in Pakistan. The data for this is not publicly disclosed but a similar philosophy reigns.

But why buy a hotel?

But why buy a hotel?

This is what it all boils down to. What we started with. SIUT is clearly an organisation that commands respect and demands replication. But why on earth are they buying a hotel? As we’ve clearly seen the organisation very much has the fundraising capacity to be able to afford the hospital. According to a recent report in Dawn, at the going market rate of Rs 220.04 per share, a 100 per cent acquisition of the hotel business should be worth Rs 3.96 billion.

As a business the Regent Plaza is relatively stable. A lot of hotel businesses were terribly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic and many have either gone under. Some of the older hotels in particular could not sustain the losses of that period because they were already in a state of disrepair. The Regent Plaza on the other hand actually made a profit for the year 2023 of more than Rs 4.4 crore according to their annual financial statement. This was, however, down from 2022 when the hotel made a profit of Rs 4.7 crore.

Now, what many people do not understand is that philanthropic companies are not a simple equation of donated money going to a simple end cause. For example if you donate money to a hospital it is not necessary that the money is spent directly on the care of a patient. In fact it is entirely likely that it could be spent to buy a new photocopy machine that the hospital desperately needs as an administrative expense. That is why a lot of donations either come to particular fundraisers (like for a new piece of equipment or a new ward) or are made out to specific causes within a charitable organisation. Similarly, a charitable organisation can also run a business on the side for profit. The profits then get funnelled back into the original charitable cause.

Now, SIUT could very well be doing this if they acquire the Regent Plaza. But what is more likely, and what they claim is the case, is that they wish to convert the building into a hospital. The apparent reason for the possible acquisition of the hotel by the SIUT Trust is its prime real estate with a built-up structure that can easily be converted into a hospital with only a few architectural tweaks. Regent Plaza Hotel and Convention Centre is located on main Shahrah-e-Faisal on an area of 13,200 square yards. The total covered area of the multi-storey building is 47,034 square yards.

The plaza is owned by a publicly listed company by the name of Pakistan Hotels Developers Ltd (PHDL). This company is what SIUT would be acquiring. Now the PHDL also possesses two other pieces of real estate with a collective area of about 14 acres located in Thatta. The latest annual accounts show the company has valued its main real estate at Rs 8.9 billion. Its hotel building is valued at Rs 93.9 crores.

Butchers for hire — the other side of the picture

So on the one side we have SIUT. It has been run for nearly half a century by a doctor that is perhaps one of Pakistan’s most legendary. It has treated millions of people free of cost and has given a model of not just how a good charitable organisation can work, but how healthcare can be provided on a government level. How patients can be treated as deserving of care rather than being blessed to receive it.

But unfortunately its example is singular. Attempts have been made to provide similar facilities. The Pakistan Kidney and Liver Institute (PKLI) is one attempt to emulate something similar but it too fell to politicking and bureaucracy. In 2018, the Supreme Court actually appointed a former judge of the SC, Justice Hameed ur Rehman, to run PKLI. He was to be assisted by a committee that consisted of a former health secretary, a member of Nepra, a retired three-star general, and exactly one doctor. In 2019, when a professional doctor was finally appointed as director of the institute, he was also dismissed and eventually placed on the ECL when the government changed.

On the other hand doctors such as Fawad Mumtaz are able to run massive and lucrative businesses with the help of political patronage. A recent report in Dawn said that the notorious surgeon has become a ‘test case’ for the criminal justice system and the law enforcement agencies, especially for the Punjab police.

“Mumtaz has been booked and arrested several times by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) and the Punjab police, but each time, he has managed to obtain bail and continue his illegal transplant racket. According to his criminal record, Mumtaz has been running the largest-ever illegal kidney transplant racket across the country, especially in Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Azad Jammu and Kashmir since 2009.”

The kidney trade in Pakistan is in fact rampant. A detailed investigation conducted by Reuters Thomson Foundation in 2017 reported that kidneys were being sold in Pakistan at a rate of sometimes just $1,000. There is no official data on the number of people who have sold their kidneys in Pakistan, but some officials estimate that there could be at least 1,000 victims every year. It is mostly foreign clients coming to the country for transplants. People selling these kidneys get a few lakhs out of this and risk their lives at worst and leave with life long complications at worst.

Even now, the latest arrest of Fawad Mumtaz came after a Jordanian woman died during one such illegal operation for a kidney. The biggest hub of this business in Pakistan is still Punjab. Why has it not caught on as much in Sindh in particular? According to the British Medical Journal, Dr Rizvi’s advocacy was instrumental in the practice being criminalised. The Sindh Institute is focused on renal disorders—60% of surgical interventions at the institute are for kidney stones—but it also offers services for those with gastrointestinal or liver complaints (it was the site of Pakistan’s first liver transplant).

This is the sort of impact a good, dedicated, government facility can have not just on people’s lives but on the larger state of things. SIUT has not just been a beacon in terms of healthcare but has proven to be a bastion for human rights and the basic dignity of life. With the state of brain drain in the country, such replications are unlikely. But one can only hope that SIUT continues to thrive and many more titans such as Dr Rizvi are around to raise walls in which lives are saved.

keep up the good work