Not for the first time, the faujis were struggling. This time, it was to do with one struggling FMCG: Fauji Foods. The ‘bad egg’ of Fauji Foundation had been a perpetual drain on the conglomerate’s resources, bleeding losses and relying on subsidies and loans from its more lucrative ventures.

What could possibly be the issue? One could assume that the dismal performance was due to a flawed governance, which placed the reins of an FMCG in the hands of bureaucrats and industrial engineers, bereft of the expertise to run a consumer centric business.

In conversation with Profit, Fauji Foods’ chief executive officer Usman Zaheer Ahmad recognised this deficiency, stating that, “It’s a fiercely competitive business landscape, and we need a talent pool that can hold its own against industry giants like Nestle and Engro.” Given the company’s track record, however, such a feat seemed like a pipe dream.

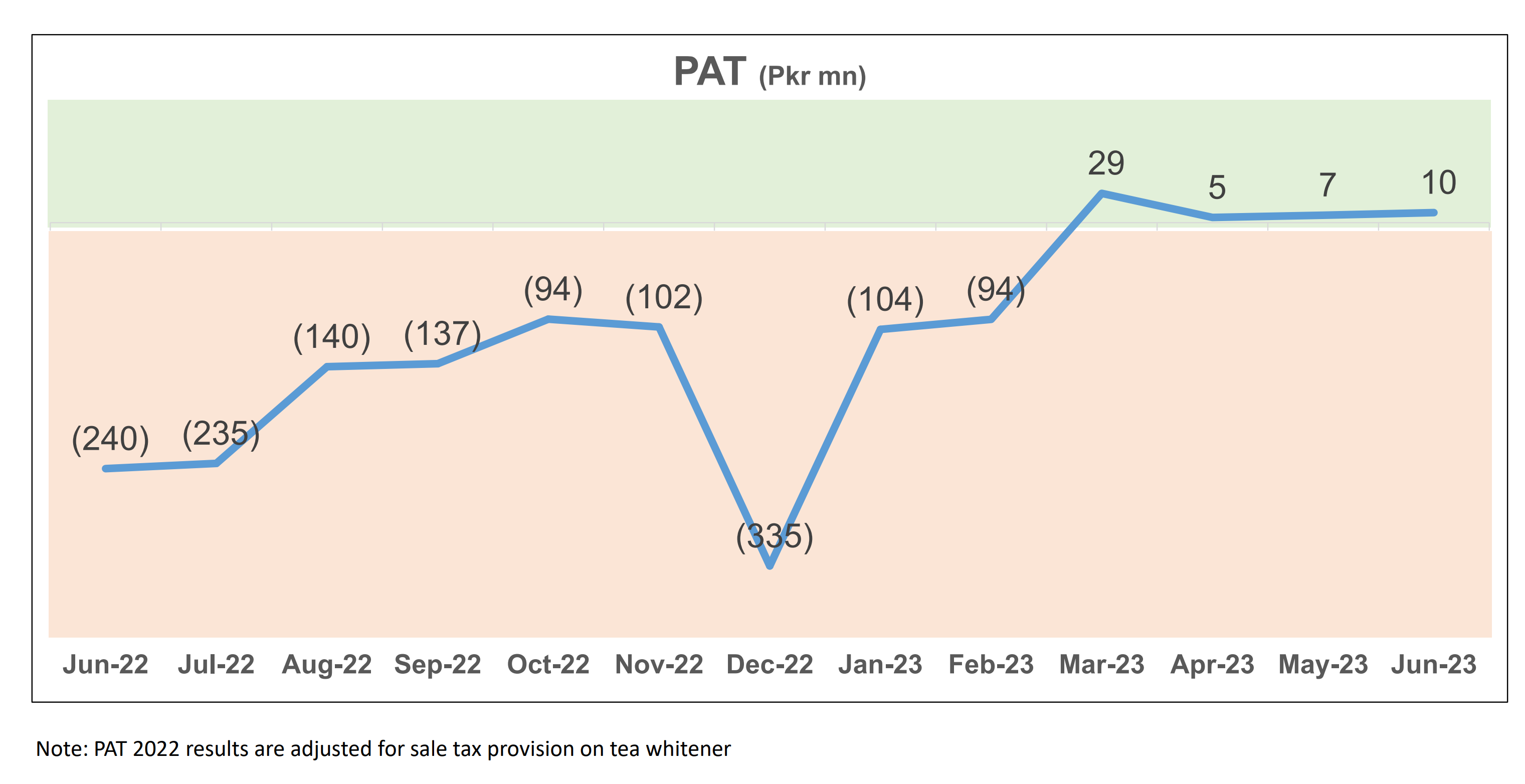

And yet, something remarkable has happened. In an unexpected turn of events this year, the company has finally turned a profit, and that too with a consecutive growth recorded in the last four quarters ending in June 2023.

How did they get here? The promising turnaround strategy that enabled this transformation involves a revamped team of professionals, a focus on value-led growth, a strategic portfolio pivot and a sustainable model of operations.

The Fauji Foundation and its problem child

Fauji Foods operates under the Fauji Foundation, which is a conglomerate owned by the Pakistan Army, with divisions spanning over sectors that include cement, fertilisers, and food.

The history of Fauji Foundation dates back to its establishment in 1945 as a Post War Services Reconstruction Fund (PWSRF) for Indian War Veterans, who fought against the axis powers in World War II. After the fund’s division between India and Pakistan in 1947, the civilian administration managed it until 1953. Subsequently, in 1954, control was transferred to the army, leading to the formation of the Fauji Foundation that makes up the Fauji Group of Companies today.

Instead of distributing the remaining balance of around Rs 18.2 million to beneficiaries, the army invested it in setting up a textile mill. This mill’s earnings were later used to establish the first 50-bed tuberculosis hospital in Rawalpindi. This marked the beginning of the Fauji Foundation’s core mission: engaging in business endeavours to generate profits for supporting Pakistan army veterans and charitable causes. Over the years, the conglomerate flourished and managed successful ventures, including ventures in the fertiliser and cement industries.

However, the foundation had not been as successful in the food industry, with Fauji Foods being a financial drain for the conglomerate.

The history of Fauji Foods dates back to 1966, way before the Fauji Foundation came into the picture. Formerly known as Noon Pakistan Limited, this legacy dairy company owned the Nurpur brand, which is a popular household name in Pakistan. Noon became Fauji Foods Limited in September 2015, when the Fauji Foundation acquired it.

According to Usman Zaheer Ahmad, the chief executive officer (CEO) at Fauji Foods, “Noon was a very traditional company. Historically, in Central Punjab, it had a good footprint. It was never a big operation but it was a good local brand. The Fauji Foundation acquired it for Rs 639 million and it was a good buy if you wanted a foothold in the dairy sector. The most important asset in an acquisition is the brand and Nurpur was already a good heritage Pakistani brand. So, in that sense, if we look at it from the acquisition perspective, it was never too big but it was a good local business to acquire and build upon.”

However, the new ownership was not able to flip the fate of its newly acquired dairy company, due to a myriad of legacy issues spanning over concerns relating to governance, financial decisions and strategy. Ahmad noted that the first thing one does after investing in a consumer business is to make a strong brand because growth and sustainability are directly linked to strong branding.

Ahmad explained that, “The early volumetric growth at Fauji, either by design or by default, came through a commoditised segment called Dostea. And there is always vulnerability where there is commoditization but no branding. This does not only result in low margins but also greater volatility. So, in the absence of a good brand equity, the margins and volumes both were constantly fluctuating.”

Instead of focusing on building the brand and securing the consumers’ loyalty, they decided to throw money at the problem. According to the company’s financials, a whopping Rs 7,260 million between 2015 and 2018 were spent on a large-scale modernisation of factory assets and infrastructure. All in debt.

Ahmad highlighted that the interest rates in Pakistan have always been quite high and such a large debt was the last thing Fauji Foods needed. “So, on the one hand Fauji Foods had a huge legacy debt and on the other hand, the commoditization also meant extremely low margins,” Ahmad explained.

And that is how Fauji Foods was set on an ill-fated course of consistent losses for years to come.

The company made a loss every single year from 2015 up until 2022. It reported an astonishing loss of Rs 2,849 million in 2018, and yet another shocking loss of Rs 5,789 million in 2019. According to its annual report of 2019, Fauji’s current liabilities exceeded its current assets by Rs 8,789 million, while its total debt amounted to Rs 13,638 million.

In 2020, revenue stood at Rs 7,373 million, which was an improvement from 2019’s Rs 5,745 million, and comparable to 2017 and 2018 revenue levels of around the Rs 7,000 million mark. Even though the company managed a positive gross profit, the jump in revenue was not enough to overcome other costs. The company’s net income in 2020 stood at Rs 3,058 million – the second biggest loss after 2019, while its financial liabilities had risen to a hefty Rs 9.5 billion.

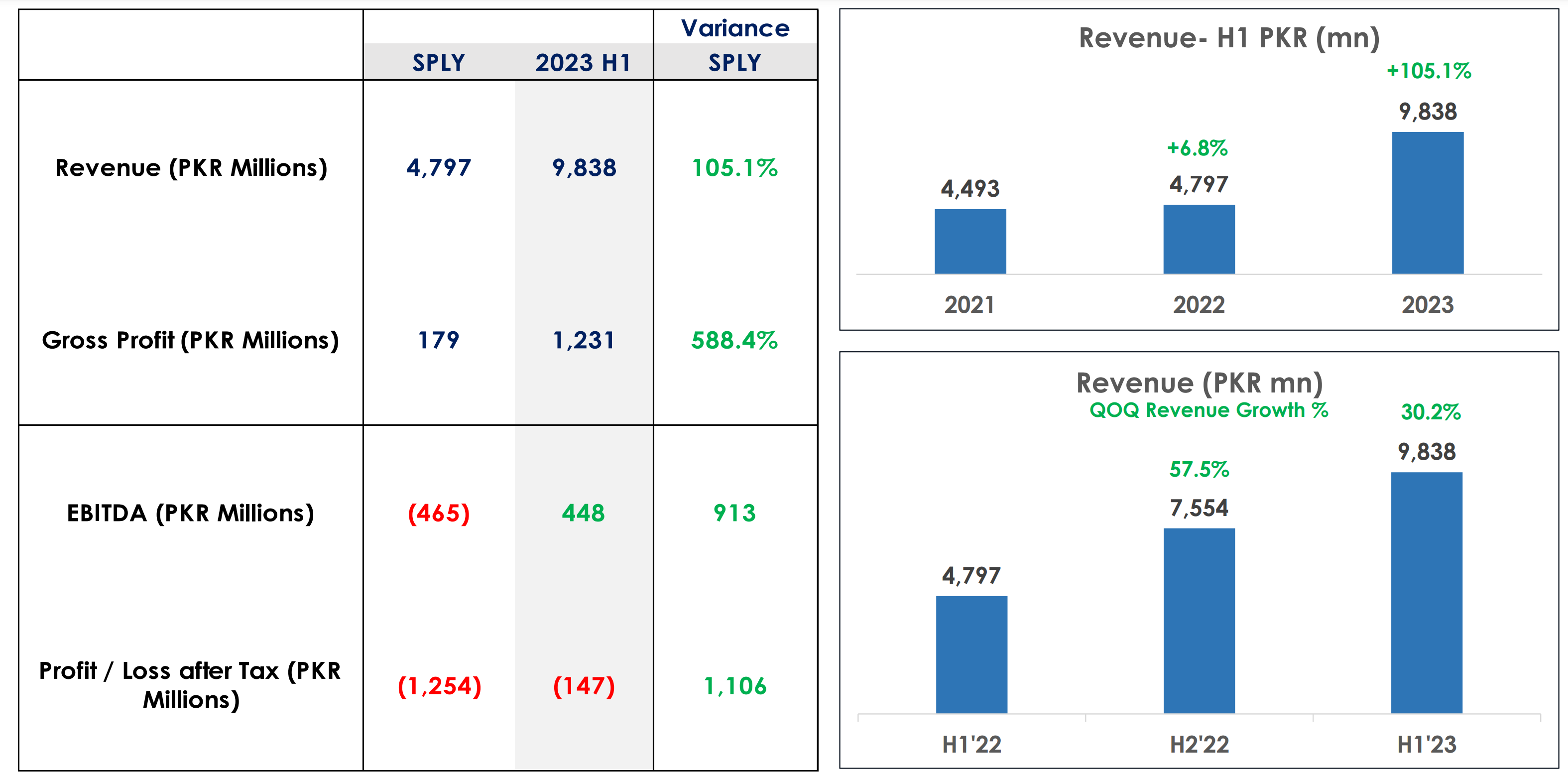

In August last year, Fauji Foods released its half-yearly financial statements ending in June 2022, which were deeply concerning to say the least. The report indicated that the company faced a staggering loss of Rs 1,253 million after taxes, a significant increase from Rs 758 million during 2021. Fauji Foods’ gross profit plummeted from Rs 545 million to Rs 178 million. The financial statements revealed a substantial rise in costs related to revenue, marketing, and distribution, resulting in an operational loss of Rs 708 million. This marked a dramatic 505% surge from the Rs 117 million recorded in the first half of 2021.

At this point, it would be fair to ask: how has the company managed to survive for almost a decade when all it has known are losses? Well, it is no secret that Fauji Foods has always relied on bailouts from the Fauji Foundation and its more successful businesses. For instance, in a stock market announcement earlier this year, it was disclosed that Fauji Foundation shareholders would be providing a loan of Rs 2.35 billion to Fauji Foods, primarily said to cover working capital requirements.

It’s worth noting that this was not the first time Fauji Foods has received aid: in fact, in 2020, Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim Ltd bailed out Fauji Foods with a loan of Rs 3.5 billion.

Read: Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim to bail out Fauji Foods with Rs3.5 billion loan – yet again

Fauji Foods onto greener pastures

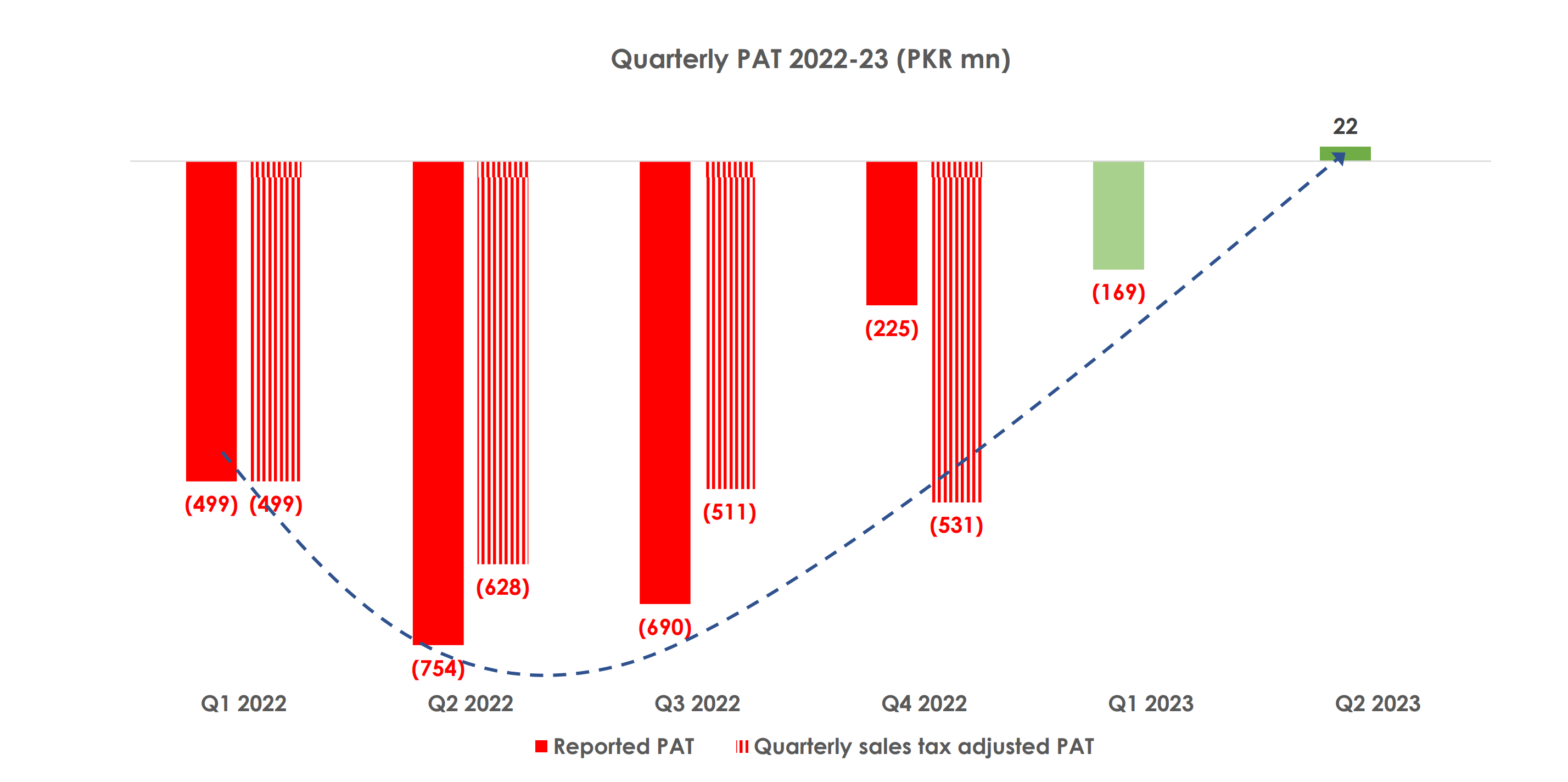

A few months ago Fauji Foods released its half-yearly financial report for the period ended 30 June, 2023. The financial quarter ending on 30 June, 2023 witnessed a net profit of Rs 22 million. In stark contrast, the corresponding quarter of the previous year reported a loss of Rs 754 million.

To express the scale of this difference, we first need to understand that moving from a loss to a profit is already a 100% improvement. However, the scale of this turnaround is even more dramatic when we consider the actual figures.

To comprehend the scale of this transformation, let’s delve into the numbers. The difference between this year’s profit and last year’s loss is Rs 776.6 million. If we consider this difference relative to the absolute value of last year’s loss (Rs 754.3 million), the percentage change would be 103%.

This means that the financial turnaround is equivalent to approximately 103% of last year’s loss. This isn’t a traditional percentage increase since we’re moving from a negative to a positive number. However, it does provide a sense of the scale of the improvement.

In essence, this is not merely about transitioning from a state of loss to a state of profit. It’s about surpassing the previous year’s losses by an additional 3%, thereby creating additional value. This granular detail underscores the magnitude of the financial turnaround achieved in this period.

Moreover, the financial quarter ending on 30 June 2023 recorded a revenue of Rs 9,838 million, while the revenue for the corresponding quarter of the year 2022 and 2021 were reported to be Rs 7,554 million and Rs 4,747 million respectively. This shows that the quarter on quarter revenue increased by 30.2% compared to last year.

This marks the inaugural instance in Fauji Foods’ history where the company has achieved a positive bottom line.

How exactly did Fauji Foods manage to pull this off? Let’s talk about Fauji Foods’ turnaround strategy that has enabled it to produce gross profit for four consecutive quarters.

Replacing the faujis

So, what did Fauji Foods do differently this time? Well, they probably grew a backbone and devised a strategy that would help them abandon their loan-seeking ways and transform the company to be a self-sufficient one.

It would be fair to assume that the root of Fauji Foods’ problems was the fact that fertiliser experts – more attuned to the industrial engineering challenges of manufacturing fertilisers – and, well, faujis, were made responsible for an entirely new type of business that was focused on consumer preferences.

Profit asked Ahmad to break down Fauji Foods’ turnaround strategy. According to him, the first pillar of the transformation was capability, because without capable people, the whole endeavour would have been rendered useless. “It’s a competitive business and you need a talent base that can compete with Nestle and Engro. So, firstly, we need the right people in the right roles, who have the capability to take on Friesland or Nestle.”

So, the company conducted training programs in-house, installed talent and performance management processes, as well as focused on talent acquisition.

In November 2020, Fauji Foods hired a new head of marketing by replacing their old chief commercial officer (CCO) with Khurram Javaid. He brought his 19 years of experience in marketing at British American Tobacco to Fauji Foods. In late 2021, the chief human resources officer was succeeded by Faisal Sheikh, whose management and HR experience spans over two decades. Not soon after, in March 2022, the company replaced the CEO Ebad Khalid with Usman Zaheer Ahmad, who had previously worked at Engro Foods and Nishat Sutas Dairy. Three months after that they brought in Wasim Haider as the company’s new chief financial officer.

When asked to elaborate on the internal governance changes and the traits they looked for when hiring a new executive and management team, Ahmad shared, “The most important thing when it came to building a new team was domain knowledge. We needed professionals from the field and that is why the common trait that you would see in almost everyone in the new team is from an FMCG and then a large number of them are from dairy specifically.”

According to Khurram Javaid, CCO of Fauji Foods, professionals with years of experience within this domain were eager to join Fauji Foods because there was a very strong notion that this is a Pakistani brand. “If you look at the dairy landscape, this is the only big local player, whereas the other big players are both multinationals. So, it was a very unique opportunity where you had room to create something from a Pakistani perspective and a Pakistani identity.”

Javaid said, “This wasn’t just Fauji Foods’ transformation but the entire Fauji Group’s transformation, with governance and executive leadership changes across the group. And when seasoned professionals from the industry saw those similar to them be incharge, they also became eager to join. So if you are working with the likes of Sarfaraz Rehman, the man behind Olpers’ and Pepsi’s success, or Waqar Malik, who came from ICI and is such a big name in the corporate world, you would want to work here too.”

This changed the general perception that the company is run by ‘faujis’. According to Javaid, prominent industry names joining the Fauji Foundation drove like-minded and talented individuals to follow suit and become part of Fauji Foods’ transformation.

Prioritising value-led growth

The second major pillar of Fauji Foods’ transformation was what they like to call value-led growth. Ahmad defines this as, “A margin accretive growth strategy or focus, whereby any new category that Fauji Foods entered or any new product it launched would be margin accretive instead of just increasing volumes.” He admitted that they consciously prioritised launches that would allow better margins.

Part of this value-led growth strategy involved Fauji Foods’ portfolio pivot.

“We always had the House of Nurpur brand but we also had a commoditized and low-margin brand Dostea. Three years ago, 85% of what Fauji Foods sold was from the commoditized brand Dostea, while the sales of value added products were a meagre 15%. During the transformation at Fauji, we flipped this ratio completely by deprioritising Dostea and redirected investment towards value-led segments such as Nurpur butter, milk, cream and flavoured milk. Now our value-added portfolio is 85% and the traditional commoditised portfolio is 15%.”

This change proved to be a good one for Fauji Foods, especially in terms of growth. Profit was requested not to share the exact growth numbers due to concerns of confidentiality, however, Javaid confirmed that after their portfolio pivot, Nurpur has become the fastest growing dairy brand in Pakistan.

Yet another arm of this same value-led growth strategy was route to market. This is a strategy concerning distribution, including when, where and how. “We digitised our approach to sales and distribution to have greater control to drive our distribution.”

The digitisation of distribution was also accompanied by a change in strategy, wherein the targets for distribution were reevaluated. “Our low-margin, commoditized products used to be distributed to over 290 cities because small volumes of it would in several cities. We concentrated distribution in the top 15 cities instead, where our value focused portfolio performs better,” Ahmad explained.

He continued, “And here we deployed state of the art digital tools for better control, visibility, penetration. These three things, including value-led growth, portfolio pivot and the reshaping and digitisation of our distribution collectively formed Fauji Foods’ basic growth propeller.”

A much needed rebranding

However, we cannot talk about Fauji’s portfolio-pivot without discussing Nurpur’s rebranding.

Javaid shared that his team did an extensive research exercise to discover what is of value to the consumers. He informed Profit that, “We wanted to know what characteristics people look for in a brand, what is being offered to them currently in the competitive landscape and whether there is a gap in the market, offering us the opportunity to provide customers with something they want but isn’t being offered to them.”

“Our next question was, can we, as a House of Nurpur, credibly own this space that our research found?” Javaid elaborated. They found that while health holds a certain priority, taste is a very important factor for Pakistani consumers. Fauji Foods’ takes pride in Nurpur butter, which they claim holds up as the consumers’ favourite local butter.

Waqas Ghani, the deputy head of research at JS Global Capital Ltd, noted that, “There has been a historical price difference between Olper’s and Nurpur, specifically within the UHT milk segment.” However, in Fauji Foods’ most recent corporate briefing, it was emphasised that they have successfully narrowed this price gap.

The re-branding also bled into restructuring of profit margins and pricing. According to Ahmad, “So, when we pivoted the portfolio, we automatically changed our set of competitors. And our competitors became Milkpak and Olpers, who are both value-oriented. Since these are our new competitors, we are at a parity price to them. We don’t sell cheaper and we can’t sell cheaper due to the value-oriented nature, and we’ve been able to pass on this inflation, especially in the last two years. So, shifting to a branded play has been a major part of this transformation.”

Sustainability for the win

The reason why Fauji Foods had been in a financial rut for so many years was inefficient spending and extremely high costs of goods sold. After doing some costing analysis and benchmarking with the rest of the industry, it was discovered that Fauji Foods’ gross margins were much higher than others. This was because their energy costs were too high.

Ahmad explained that energy in the factory is used for two components, including power and for steam processing of milk. They were using heavy fuel oil (HFO) for power and coal for steam processing.

“To tackle this, we took two major initiatives that took us to greener and cheaper energy. We have shifted all our steam production to bio-fuel. This is taken from the stubs of crop waste that is usually burned to discard, which is a major pollutant as well. We buy these stubs to use as green fuel and we have completely eliminated the use of coal,”

The ash produced from the crop waste after burning it is sold back to farmers which they then use as fertiliser, creating a circular system that limits wastes and promotes recycling. Additionally, a 1MW solar plant has been installed to limit the reliance on HFO for power. While reducing their energy costs, Fauji Foods has also significantly reduced its overall carbon footprint. Ahmad said that these changes were introduced last year and became fully operational during the first quarter of this year.

Another cost cutting strategy that Fauji Foods implemented was localisation of packaging materials. Ahmad told Profit that some stock keeping unit (SKU) packaging materials used to be imported, but due to the import bans, a global surge in material prices after the Ukraine-Russia war, as well as the rapidly devaluing rupee, continuing to import those materials was not viable or sustainable.

Lastly, the company addressed some issues it had been ignoring for years on the financial front. According to Ghani, “When we talk about earnings, it also includes financial charges, which dropped significantly during this time. Fauji Foods’ financial charges on average were 300 million per quarter for the past many quarters, but for this last quarter in June, the charges were 36 million only.”

This sudden drop was due to the payment of a debt amounting to roughly Rs 8 billion, which is no longer reflected in Fauji Foods’ balance sheet. “We don’t have the latest financials for June but in March they mentioned this in their financial reports. So, this debt will no longer drag their performance,” Ghani concluded.

How have Fauji’s competitors performed?

We cannot talk about Fauji Foods without talking about other prominent dairy companies such as Nestle and Engro-FrieslandCampina.

According to Pakistan Dairy Association’s (PDA) economic survey 2022, despite being the third largest milk producing nation in the world, only 7.4% of our milk is processed and packaged. The rest of the 92.6% milk is unprocessed, unregulated and untaxed. This means that the three main companies operating within the formal dairy sector only make up 7.4% of the pie, while the informal sector takes more than 90%.

Within this small formal sector, the division between the market share among the three main companies remains undocumented. However, we can still gauge the profitability of each company over the past year.

In the quarter culminating in June 2023, Nestlé posted a profit of Rs 5.32 billion, a significant surge from the Rs 3.24 billion reported in the corresponding quarter of the previous year. This equates to a substantial increase of approximately 64.2% from the previous year. However, comparing Nestlé’s profit growth with that of Fauji Foods may not provide a fair comparison due to Nestlé’s considerably more diverse portfolio and the undisclosed financial results for their dairy segment.

Meanwhile, Engro Foods’ FrieslandCampina reported a profit of Rs 1.33 billion for the quarter ending in June 2023. In contrast, the net profit for the corresponding quarter of the previous year was Rs 938.17 million. This denotes a notable increase of approximately 41.4% from last year.

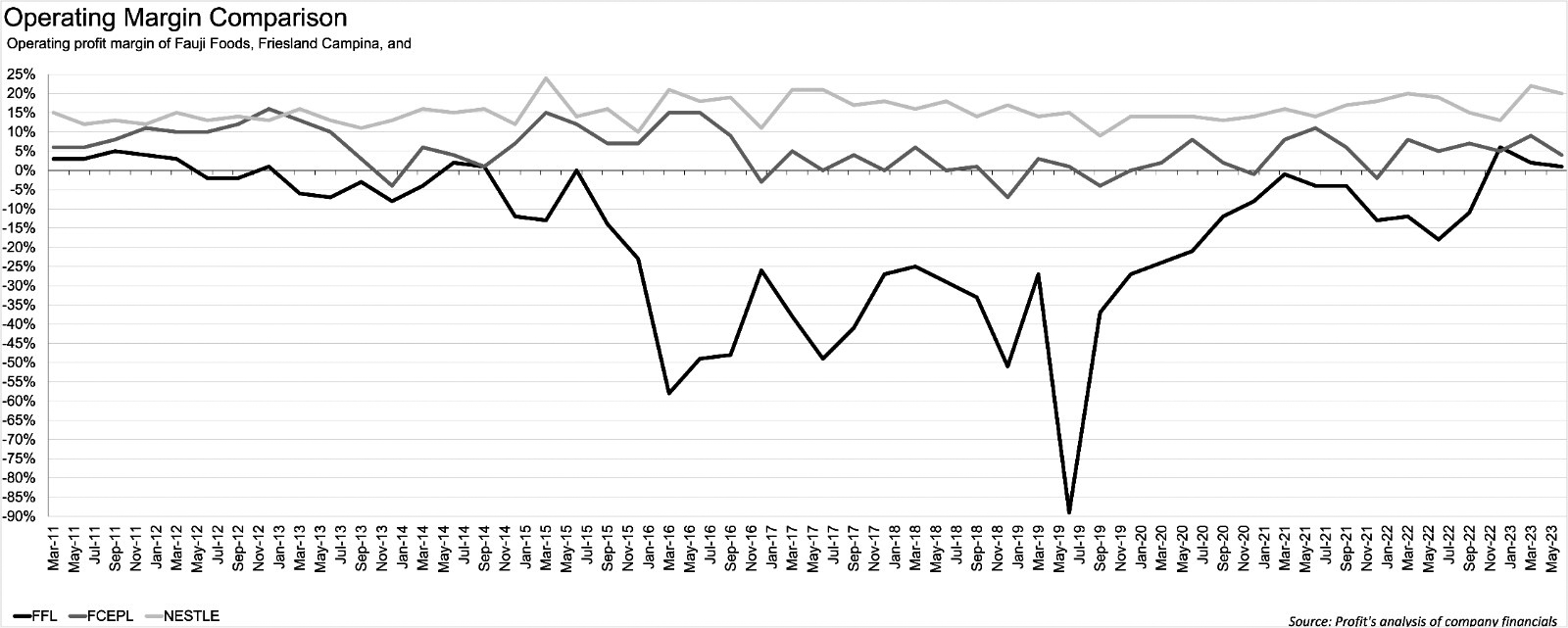

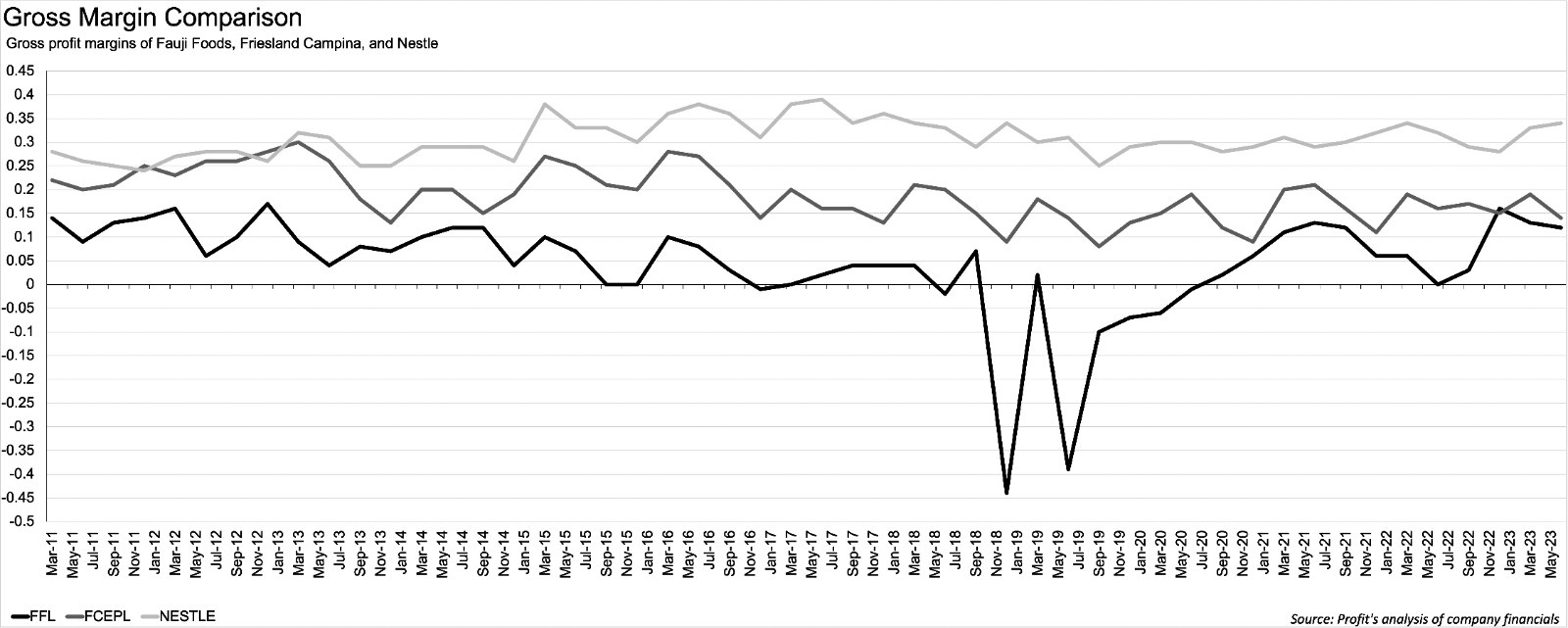

Over the past 12 years, the operating margins of the three companies have witnessed great fluctuations, with FFL experiencing the highest growth among the three in the past four years.

One can see Fauji Food’s exceptional growth since 2019 in the line graph depicting the gross margins of all three companies.

While Nestle and Engro continue to stay on a trajectory of growth and profitability, this is the first time that Fauji Foods Ltd has joined the race and recorded a significant 103% hike in net profit in just one year.

Ahmad argued that, “This is not a seller’s market, so the production capacity and the size of a company matters, but just because you can produce it, doesn’t mean you can sell it. It is a very competitive consumer business. So once you are in the market, you have to earn the share from consumers.”

Abdul Sattar Babr, the CEO of multinational market research and consulting company IPSOS believes that this is not a unique event. According to Babar, “Pakistan’s dairy sector is one of the worst performing sectors and it has been this way for years. Markets like India and China were introduced to packaged milk at the same time as Pakistan was, however, they have adapted to it much faster than Pakistan.”

Babar argues that the real competition lies not between Fauji Foods and other competitors, but in the massive unregulated market. Instead of capturing the existing market share, companies could shift their focus to market conversion, and thus experience better and faster growth.

Ahmad, agreeing with Babar, asserted that, “In the long term, every dairy player that is in Pakistan, is in this for conversion and that’s what makes this market attractive. That is why Nestle chose to come in Pakistan and also why Friesland acquired a business and made an investment in Pakistan. That is why our group is in the dairy business because dairy culture exists in Pakistan. It is a consumer market and this is an opportunity.”

“20 years ago loose milk was sold in Turkey, just like it is in Pakistan today. However, a consensus was developed around the world and on a scientific basis that it is impossible to preserve the goodness and nutritional elements of milk in a supply chain in loose form, countries changed their consumption behaviours and adapted,” added Ahmad.

He believes that our regulators have acknowledged the importance of processing, storing and selling milk through an organised and safe procedure, but they lack the resources to formalise the sector completely. However, as our societal and segmental awareness increases, the conversion will happen. “It is bound to happen,” he said.

Industries such as FMCGs rely on agile and rapid decision-making, along with fast-paced marketing approaches, to adapt to shifting trends and maintain a competitive edge. After almost seven years of operating as an archaic and traditional organisation, Fauji Foods has finally made drastic changes in both, their governance and operations. But most importantly, they have invested in developing their brand, which is a necessary requisite for battling the volatility characteristic of consumer centric industries.

Look no further than a YouTube party! Enjoy YouTube with your friends, or loved ones, no matter where you are. Use live chats, videos, and calls to talk and have fun together. It’s like having your own showtime parties, even if you’re far away!

Let’s party now with Amazon Prime Watch Party, you and your friends can watch Prime Video together. No matter how far apart you are, have a blast with synced videos, chatting together, and even making video calls while using your favorite streaming site.

I have been searching for a way to get my eBooks on my kindle for SOOO LONG!!! This was so helpful, THANK YOU!

Well researched and informative article.

A very good and detailed insight of a national company turned around from a loss generating company to a profitable venture.

I am a profound visiter of local supermarkets to meet my grocery needs. And always prefer local brands like Nurpur. But I find other brands like Haleeb at promotion or on lesser price. While their quality is also comparable. So something must be done to be more competitive in milk sector to increase the customer base.

I am a loyal consumer of Nurpur butter for more than a decade. And for the last two year buy 1 kg pack, which is economical for our household.

But at various occasions it is not available in Bin Hashim and Carrefour. Further more it’s a packaging must be improved for better hygiene and to protect from human touch.

Keep it up towards further progress.

fauji food makes ones of the best products

Is Fauji Food public listed company

Nadeem

hi cal me

Loose will never lose its significance because packaged milk is cancerous and people are fools to believe otherwise especially when cream has been removed and readded. Secondly its a personal choice and no one can be forced to buy packaged processed food that is carcinogenic hands down. Even the lining inside the package has pb layer, milk has formalin and pesticides or worse other unknown elements.

Why force ur junk product on people they are able to decide what they want and conglomerate culture will not win this game hopefully no matter how uch propaganda machinery you have activated.

A very good company with yummy products introduced such as oppa frozen products line was the game changer i think i really wanted to go and work there as an engineer but things didn’t work out as planned. Anyways best of luck to this prestigious industrial estate making good and fresh food and dairy products

Fauji Foods proved itself to be the best. thanks to Mr. Waqar Malik CEO & MD Fauji Group

“This post was a rollercoaster of emotions. Beautifully penned.”

“I appreciate the balanced view you presented. It’s rare these days.”

This is really creative kind of blog post, I love it a lot.

love to read very great article