Hardly anyone is happy with the latest federal budget. Salaried class, factory owners, real estate developers, all have showcased their disappointment over the government’s lack of vision and exploitative policies. But one sector that is particularly unhappy, contrary to the status quo, is the textile exporters.

Over the years, due to a recurring balance of payments crisis, Pakistan has done its best to facilitate exporters. Not only have they been given tax breaks but major subsidies have been redirected their way to make them competitive in the international market. This year however, the government had to decide between cutting the exporters’ leisure or cutting their own and they decided to go with the former in the latest budget.

The government has taken away the exporter’s leisure of not giving tax on profits and imposed a tax rate of 29% on their profits. Meanwhile the previously applicable 1% tax on revenue has not been fully abolished but rather revised such that companies that do not make a profit will still have to pay it.

The decision has been heavily criticized by not only the industry itself but the larger business community including the sectors that have, over the years made a case for taxing the textile sector. So what is so bad about this new tax regime?

Textile Taxes over the years

Over the last two decades, the textile industry in Pakistan has seen a host of protections. It is perhaps these relaxations that have set an unfair number of expectations in the minds of the industry stakeholders.

Pakistan is a country that is often short on foreign reserves. On other occasions, the country always faces a direct balance of payments crisis, that it usually has to offset with the help of foreign aid. Any industry that hence provides any breathing room in terms of forex should be encouraged by default. Since 2005, textile, especially export oriented textile has been that particular industry.

The industry has always had exemptions and concessions for export oriented textile mills, but in 2010, the minimum tax on turnover was introduced for these mills. This rate was fixed at 1%.

Several subsidies on utilities by the government, duty drawbacks, sales tax exemptions and export refinance scheme by the state bank, provided an umbrella for the industry over this period, failing to capture a sizable market share in global textile.

This was up until 2023, when a super tax was imposed on the industry after the country fell short on tax revenue. What came about as a 1 time measure, lingered making the industry only slightly in the global market.

However the recent introduction of the 29% income tax rate on profit, puts the active tax rate well over 50% of the textile company’s profit margin, making it significantly non competitive in the global market.

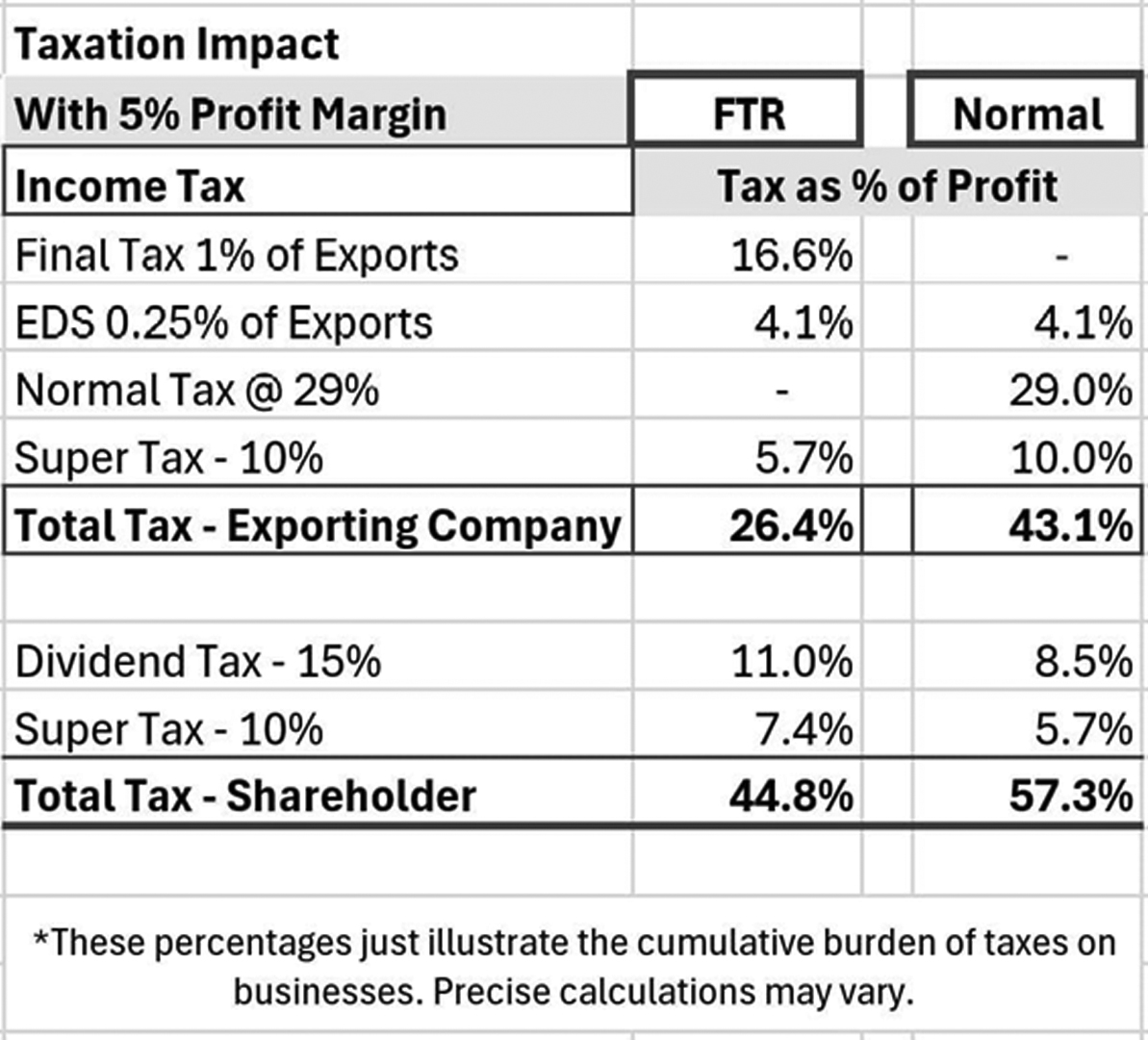

More importantly, the government has now shifted from the previous Final Tax Regime (FTR) to a Normal Tax Regime (NTR) for the exporter. Previously, the exporters only paid 1% on turnover and under certain circumstances, a 0.25 on Export Development Fund/Scheme (EDS).

Under this new regime, the exporters will also pay 0.25 % Export Development Fund (EDS) and this cost increase cannot be transferred to foreign buyers. Moreover, they will pay either of the two taxes, a 1% tax on turnover and 29% income tax on profits, depending upon their profits. In essence, the FTR hasn’t been abolished, it has been reimposed on top of the NTR.

The philosophy of being taxed

It is important to note that a company is expected to be taxed more than an individual. Similarly, bigger businesses intuitively pay more taxes than smaller companies due to their sheer size and profitability potential.

Imagine a company as a large farm and an individual as a small garden. The farm (corporation) has more resources and generates more produce (profits) compared to the garden (individual income). Since the farm uses more public resources like roads for transportation and infrastructure for business, it’s fair for the farm to contribute more to their upkeep. This ensures the farm pays its share for the benefits it enjoys and supports the community.

Setting tax rates also involves balancing. If the farm’s taxes are too high, the owner might plant fewer crops (invest less), affecting the overall harvest and economic growth of his region. If too low, the neighborhood might not collect enough to maintain shared facilities. So, governments set corporate tax rates to encourage businesses to invest while ensuring they contribute adequately to the community’s needs.

Another thing that sets corporate taxes apart from individual taxes is that they represent the residual after expenses, meaning corporations have a better ability to pay. Individuals are taxed on their income, which often includes necessary living expenses, so their rates should generally be lower to avoid excessive burden.

But what if a company makes a loss? Typically, companies that make losses do not pay income tax in Pakistan. But the minimum turnover tax does not make that exception. Companies in the textile sector that have been making losses over the last few years, have been subject to paying an additional cost in terms of turnover tax.

Over the years, the textile industry has been an exception to these rules of corporate taxes. Minimum turnover tax meant that a company that had a profit margin of close to 10% would pay less than 10% in taxes. However this year the government has decided to correct that.

Not only did it not remove the minimum turnover tax, it also added a normal income tax at 29%. Any company had to pay at least the 1% turnover tax and at most the 29%+10% tax along with other withholding taxes, taking the rate to above 40%..

The real effect

40% is just the nominal effect. The real impact of this newest taxation regime is much higher. According to data shared by the Pakistan Business Council, the effective tax rate on the textile exporter will cross 43% of the profit, if their profit margin is 5%. Translate this onto the shareholder with the increased capital gains taxes, the effect crosses more than 57%.

The council makes the case that this will discourage not only the foreign investor but also force the local industrialist to close up shop from Pakistan and set it up somewhere else.

Increasing taxes on exports is a tricky exercise because when the tax on any industry is normally increased, they translate that into an increase in prices. The burden is passed on to the consumer and the industry takes only a small hit in demand. In export it is an entirely different game. Export-oriented companies compete with other companies from around the world.

Their products are supposed to be of a better quality and are hence not as well received in the local market. To make it big in the international market they have to be good but also competitive, i.e, cheap enough for the international buyer to prefer them over the others.

Pakistan’s competition currently is countries like Bangladesh, India, Vietnam and China etc. Despite giving special tax breaks to textile, it was nowhere near the competition even in the past. The Pakistani industry is using electricity almost two times as expensive as some of these countries, and have to pay a super tax on top of the regular tax.

According to State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) data in FY23, textiles accounted for around 60% of Pakistan’s exports, and in FY24 between July to May, they accounted for around 53% of the country’s entire tax portfolio. This was after

Who is behind the change?

So if leveling the taxes for the textile industry brings about so many complications, who came up with this idea? This is where it gets interesting. According to credible sources, the idea was given to the finance division by none other than All Pakistan Textile Mill Association (APTMA) itself.

But why would APTMA shoot itself in the foot? To answer this we first have to understand the types of textile mills. APTMA is a body that represents all textile mills. This includes spinners, weavers, and garment manufacturers etc). While the spinners are not a high value added producer and exporter in the industry, they are a large share of it. The others often have similar concerns and benefits and hence can be clumped together as non-spinners.

Oftentimes the policy requirements of spinners and non-spinners has not been historically aligned. Now APTMA not only represents the best foot forward of all kinds of textile producers, it also mediates differences between them.

To understand just how important APTMA is, it is important to note that Gohar Ejaz, former commerce minister, was previously the chairman of APTMA, which some believe led to his political prominence.

Disputes within different kinds of textile millers have been common at APTMA, be it disputes on subsidies and tariffs or be it controversies on export of yarn. In 2011, a serious dispute over the export of cotton yarn was observed between spinners and non-spinners. Local spinners started exporting large quantities of yarn due to high international demand, leaving little for the domestic weavers and garment manufacturers. This eventually led to an export quota being set up by the government. It was believed that the decision was heavily influenced by lobbying from non-spinning sectors within APTMA.

Now ever since the rupee has become expensive in FY22, the value added sector has been making the bulk of the bank. As an example, in FY23 Interloop, a leading export-oriented textile company made a 17% after tax profit and saw a 63% growth in its profits. While the entire industry got to pay the 1% tax, the value added sector got the bulk of the benefit.

To compare, a spinning giant, Nishat Chunian, made a loss in the same year close to 1% of its revenue. And one of the things that the company would have really benefited from is the abolishment of the tax on turnover. It is believed that due to this disadvantageous market position, the spinners were the ones at the forefront of the abolishment of the tax on turnover and reenactment of a normal corporate tax regime. The logic is that if a company makes a loss under that, they do not have to pay income tax and can also offset their tax expenses for the upcoming years.

It sounds like a perfect goal to lobby towards especially for loss making spinners. However a government which is severely short on cash did the exact thing that both factions did not want for themselves. An all encompassing tax that would hit turnover, if you made a loss and profits if you make a profit. On top of a flat 10% in the form of a super tax.

This put all the lobbyists and the interests they represented at a disadvantage.

What will happen now?

While this suppresses business and reduces exports, one serious concern that the government faces is the withdrawal of investment, such is the nature of industrial policy based on a free-market economy. So the government really needed to do something, and so it did.

The commerce ministry has formed a committee to address and accommodate the concern of the exporters. Will this committee and its findings amount to anything? No one can guarantee.