Fauji Foundation, the military-owned diversified industrial and financial conglomerate, is now eyeing a new frontier—the steel industry. Known for its presence in fertilizers, food, energy, banking, and more, Fauji is looking to acquire Agha Steel. But is this move a shrewd step into a growth market, or a plunge into troubled waters?

There are three key variables are key to answering that question. The first is Fauji’s own ability to manage ventures in its ever-expanding and diversifying empire. The second is whether Agha Steel is the best acquisition target in the space, or at least is it one through which Fauji can have a realistic expectation of making a reasonable return. And then the third is the economics of the steel industry itself, and whether or not it is a good industry for Fauji to expand into.

Fauji’s conglomerate

The Fauji Foundation was set up in 1954 as a welfare organization originally meant to support veterans of World War II from the area that is now Pakistan. Its initial capital came from the recently-departed British government. The foundation set up a textile mill, a sugar mill, and a cereal mill from those funds to create a flow of ever-growing dividends that would support the foundation’s grants to the veterans and the families of deceased soldiers.

Over the decades, the foundation expanded its activities, and most notably, in 1978, entered the fertilizer manufacturing business. Fauji Fertilizer Company was set up as a joint venture with the Danish company Haldor Topsoe. he first urea complex was commissioned in 1982 in Sadiqabad, Punjab. To keep up with the urea demand in the country, a second plant was built at the same location in 1993.

Fertiliser are now the core business of the conglomerate. In 1993, a second fertilizer company – Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim – was incorporated and began production of phosphate-based fertilisers in the country.

Both Fauji Fertilizer Company and Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim are among the most consistent dividend-paying companies in the country, in part because they sell a product for which there is almost consistently growing demand every year and the country does not produce enough of it. Fauji Cement is somewhat less consistent in terms of paying dividends, but is nonetheless also a major piece of the conglomerate.

As was stated in a recent analysis of Fauji’s business, part of what makes Fauji unique is the insistence on hiring retired soldiers at the top levels of the company. This has certain consequences which lean into some stereotypes about military men: they do well when the product is industrial and requires disciplined adherence to a strict production process, and much less well when they try to sell consumer goods that require creativity in creating brands that appeal to a mass audience.

So, for instance, Fauji Foods struggled even after acquiring well-known Pakistani brands from Noon Pakistan, which owned the Nurpur brand of butter. It required civilian management to come in and steer the ship, which appears to be struggling again now that it is back under military control.

By that logic, Agha Steel – an industrial entity – is absolutely consistent with the conglomerate’s strategy: it represents the kind of business that Fauji has a strong track record of managing. But there is at least one wrinkle in this decision: it seems to be going against what appears to be a move to simplify the complexity of the conglomerate.

Fauji has been on a simplification kick of late. It is in the final stages of merging Fauji Fertilizer Company and Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim into a single entity – a move many market observers believe was long overdue. In 2022, it merged Fauji Cement and Askari Cement to become one of the largest cement manufacturers in the country. And it has folded its investment banking and securities brokerage arm – Foundation Securities – under the umbrella of its bank: Askari Bank.

All of these moves were completely logical and certainly reflect a healthy instinct: cleaning up the governance structure of a complex conglomerate that had grown unwieldy over time. It is also reflective of a reality that is at the heart of every business question around diversification: there is only so much attention that senior management came give to any business line, which means it is entirely possible for a conglomerate to overdiversify.

But is it even right to think of the Fuaji Foundation as a conglomerate? Or it is really more similar to a strategic investor that just happens to prefer a strategy of majority ownership in all its portfolio interests, but otherwise leaves day-to-day management of the companies to the managers it appoints?

If it is the latter, then an investment in Agha Steel is merely deployment of surplus capital to generate returns in a business that is similar in nature to ones that the portfolio manager already owns. And perhaps the acquisition decision is more logical.

Which then leads us into a discussion of whether or not Agha Steel itself is the right play in the steel sector.

The steel contender: Agha Steel

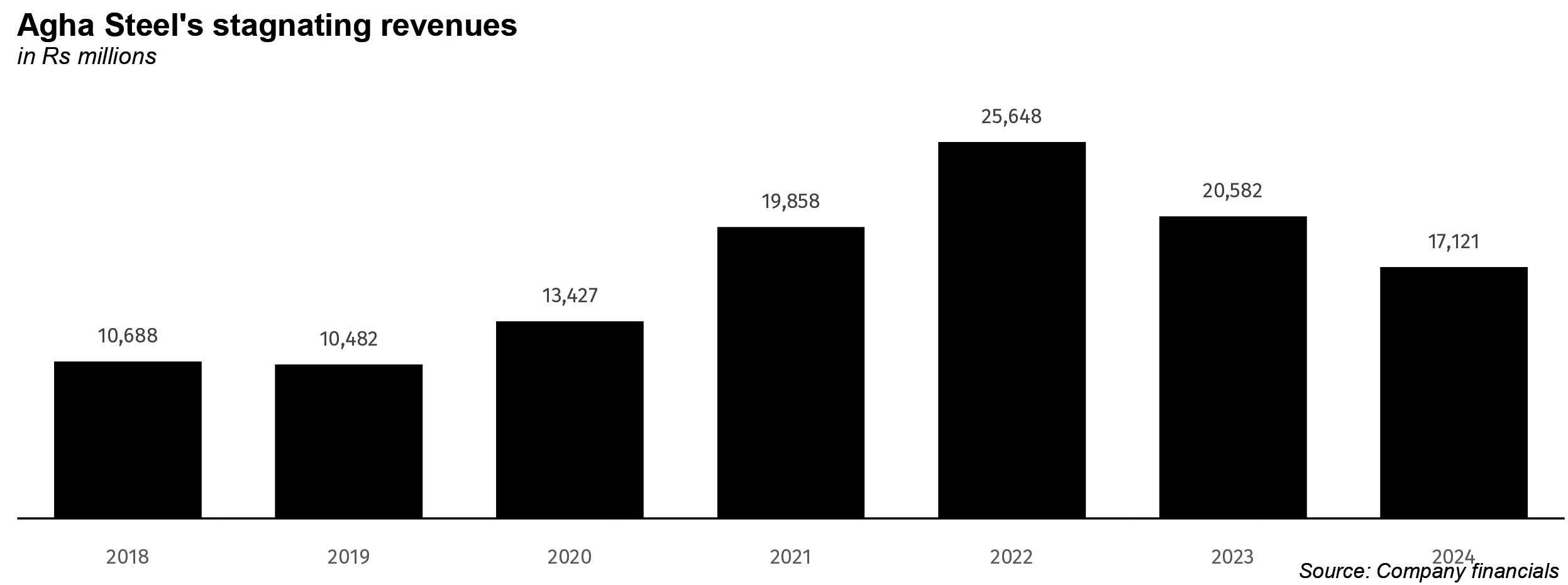

Founded in 2012, Agha Steel has carved a niche for itself in producing rebar and billets with an annual capacity of 450,000 and 250,000 tons, respectively. The company posted impressive revenue figures, clocking in at Rs20.6 billion for the year ending June 2023, along with a net profit of Rs905 million. On the surface, these figures suggest financial strength, but a deeper dive into industry comparisons raises some eyebrows.

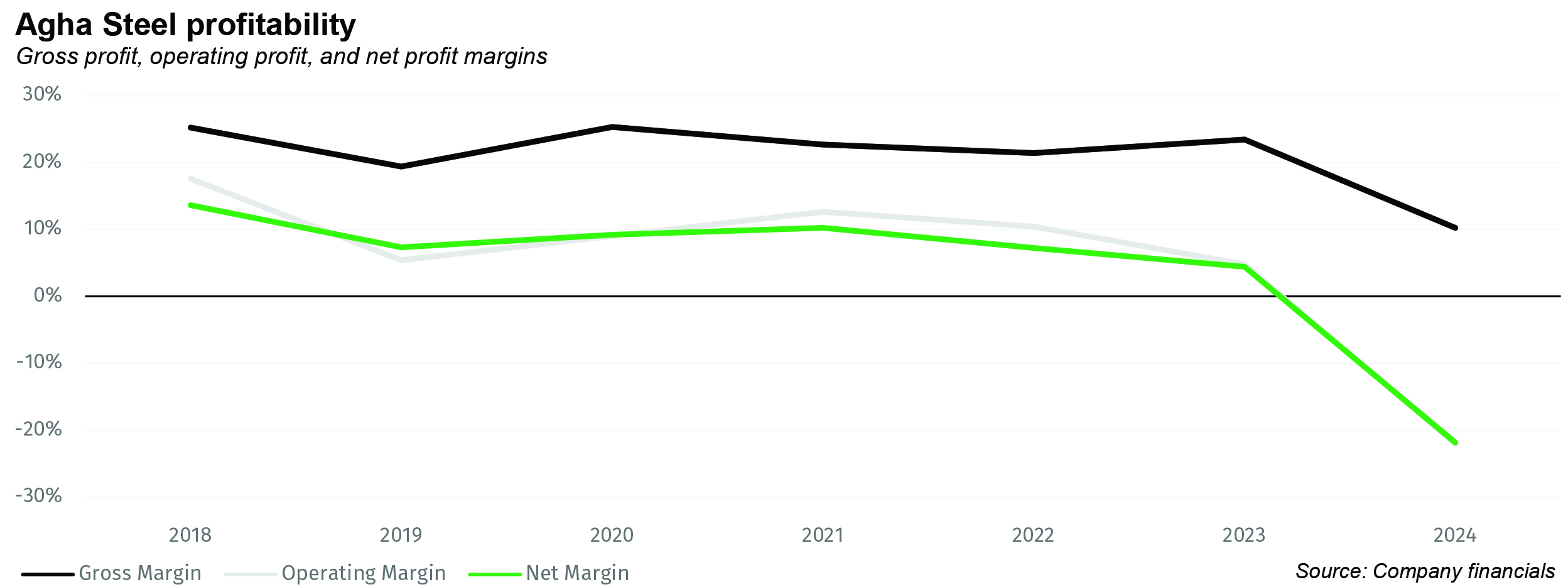

Over the past six years, Agha has managed gross profit margins ranging between 20-25%, significantly outperforming the industry average of 7-15%. However, recent downturns paint a different picture. Gross margins slid to 10%, and net profits turned negative at -22% in 2024. In contrast, its competitors saw more stability, with industry gross margins of 14% and net profits holding at 4.6%.

So what went wrong? In a word: leverage.

Agha Steel has way more debt on its balance sheet than its competitors, and it shows up in terms of how much more it has to spend on interest expenses compared to its rivals.

Agha’s financial struggles seem tied to its ballooning interest expenses. Borrowing is routine in the steel sector, but Agha’s debt servicing has spiraled out of control, with interest expenses surging from 3.92% of sales in 2018 to a staggering 28% in 2024. The reason? Sky-high interest rates imposed by Pakistan’s central bank, peaking at 22%. While the whole industry has felt the pinch, Agha’s borrowing practices have exposed its vulnerability more than most.

Its competitors? They saw their interest costs rise, but nowhere near as dramatically, maxing out at around 6.6% of revenue. Agha’s inability to renegotiate better credit terms is clearly costing it dearly.

Agha’s liquidity is another issue. Its current ratio—a measure of how well it can cover short-term liabilities with short-term assets—has deteriorated from a healthy 1.28 in 2021 to just 1.02 recently. Even worse, its quick ratio, which strips out inventory, has hovered at dangerously low levels, recovering only slightly to 0.55 in 2024. By comparison, industry players have seen stable ratios, giving them more breathing room amid economic turbulence.

Agha’s heavy reliance on short-term borrowing to fund operations has left it highly leveraged. While its debt relative to its property and equipment has fallen from 108% to 74%, the industry average remains higher, with competitors reducing their own debt loads more slowly. Yet, despite borrowing less, Agha’s inefficiency in managing this debt is undermining its profitability.

So what exactly is the problem? Why does the company carry so much debt? Because it seems to carry over eight months of inventory on its balance sheet at all times, and finances that inventory through debt. That only happens when a company is producing far more than it can actually sell, or it is exceptionally bad at planning out how much it expects demand to be.

Agha Steel, perhaps in the hopes of growing its revenue faster than it actually has the capacity to, keeps on producing a lot of steel, but then does not actually sell it at the same pace as it produces, and somehow has not thought to just stop production for a while so as to run down its inventories.

If the company did that, it would be able to sell its inventory, and use the cash received from the sales to pay down its short term debts. That, in turn, would dramatically reduce its interest burden.

That might be seen as bad, but if you are a potential acquirer, having a company’s management making such elementary mistakes is good: it means there is a clear path to fixing the asset quickly and boosting profitability without having to do a lengthy and time-consuming examination of what would be the right strategy to make the company grow.

The market’s view

Investors do not seem too optimistic about Agha Steel. For every rupee of equity, the market is willing to pay just Rs0.59, compared to its competitors Aisha Steel (Rs0.42) and Amreli Steel (Rs0.56). On the other hand, better-performing companies like International Industries and Mughal Iron & Steel command a premium, with price-to-book ratios above 1.0.

Similarly, Agha’s price-to-earnings ratio sits at 9.42, while the broader industry averages 12.4. Investors are clearly more willing to bet on companies they see as having stronger earnings potential. In other words, the market is clearly less optimistic about its sales potential than Agha Steel’s own management, and judging by the mess on the company’s balance sheet, the market is probably right.

That lower price, again, represents an opportunity for the acquirer: if the market is pricing the asset low, but a change in management and a few simple changes in strategy can result in a higher profitability for the company, that lower price is a good thing from Fauji’s perspective.

Steel’s macro risks

Zooming out, the steel industry faces its own set of macroeconomic challenges. Steelmaking in Pakistan relies heavily on imported raw materials, with iron ore and scrap metal comprising 60-70% of production costs. Between 2018 and 2024, scrap metal prices doubled, only to fall back to earlier levels. Yet, the rupee’s sharp depreciation has eroded the cost advantage this drop should have provided. Steelmakers are now grappling with a dollar that trades at Rs 280—up from Rs 100 just a few years ago.

The industry’s fortunes are tightly bound to exchange rates and raw material prices. Any fluctuation in either could make or break Agha Steel’s recovery.

Despite these headwinds, there’s a silver lining: Pakistan’s steel consumption per capita stands at a mere 36 kilograms, far below the global average of 200 kg. There’s room to grow. Recent government commitments to infrastructure projects, including a Rs 1.4 trillion Public Sector Development Program, could spur demand for local steel.

Additionally, with the central bank’s recent decision to slash interest rates from 22% to 17.5%, the cost of financing is expected to fall. For Agha, which has struggled under the weight of expensive short-term loans, this could be a much-needed break.

The verdict: is Fauji’s gamble worth it?

Agha Steel is undoubtedly a company with potential but one that’s currently bogged down by debt, inefficient capital use, and market skepticism. Fauji Foundation’s planned acquisition could breathe new life into the struggling steelmaker—but only if it tackles the internal financial woes plaguing the company.

Meanwhile, the steel sector itself remains a mixed bag. Macroeconomic volatility and competition from cheaper imports, particularly from China, Russia, and Ukraine, will continue to cast shadows over the industry. Yet, with rising domestic demand and easing borrowing costs, Fauji’s gamble could just pay off—if it plays its cards right.