Everyone wants to get into the venture capital business these days. Even old-line electric utility companies, it seems.

K-Electric, the company formerly known as the Karachi Electric Supply Company, announced on Tuesday, October 27, 2020 that it is creating a venture capital fund – the KE Venture Company (Pvt) Ltd – with an investment of a paltry Rs275 million ($1.7 million).

“The creation of KEVCL is part of the diversification strategy of the Company to get into allied business and create new revenue streams for KE. KEVCL will be a subsidiary of KE and is intended to be the holding company for all such investments to be made by KE,” said Muhammad Rizwan Dalia, company secretary, in the public statement issued to investors through a notice posted on the website of the Pakistan Stock Exchange, where K-Electric is publicly listed.

Large companies creating their own venture capital arms is nothing new. It happens in the United States and Europe all the time, and even some Pakistani conglomerates have created venture capital arms, such as the Fatima Group (with Fatima Gobi Ventures), the Lakson Group (Lakson Ventures), and others. What makes K-Electric’s announcement fascinating is that this fund is expected to be in the renewable energy space, and the fact that it is so tiny.

Let us discuss the size of it first. Pakistani venture capital is still a nascent industry, with the largest dedicated Pakistani fund being Sarmayacar Ventures, which has only about $30 million in assets under management. In most parts of the world, the largest Pakistani fund would barely have its head above the line of being called a micro-fund.

So, announcing the creation of an entity, funding it with $1.7 million, and calling it a ‘venture capital fund’ does not really make sense. At least not until you see what it is supposed to be used for.

“[KEVCL’s] investments would include, but are not limited to, initiatives in the renewable energy space. The current initiatives planned are in the utility scale generation landscape and the distributed generation market,” said Dalia, in his written statement.

Those last three words are especially critical, and represent – at least on the surface – a change in attitude by the K-Electric management. Until relatively recently, K-Electric has been quietly lobbying against renewable electricity in Pakistan, especially against having to enter into agreements with household consumers to purchase the surplus electricity from their rooftop solar energy systems.

Why? Because the government’s regulations were a little usually favourable towards the owners of rooftop solar panels and – in K-Electric’s view – did not create an arrangement that would be profitable for utilities like K-Electric to enter into.

Here is why: the government currently requires utilities to buy electricity from households that have solar electricity at only slightly less than the same rate that it sells electricity to them, effectively meaning that the utilities have to buy electricity and then sell it to other users with very little margin left for the use of the expansive electricity distribution infrastructure that they own and maintain.

But this is not the only problem K-Electric has. While K-Electric has 2.5 million customers spread throughout the city, about 40% of its revenues come from just 2,500 of its top industrial customers. Most utilities have relatively high concentrations of their customers, so one might think that this is not a big problem. But here is where things begin to get really interesting.

Solar power is becoming increasingly cheaper and with advances in battery technology, is becoming competitive with the prices charged by the grid. It has the added advantage of being uninterrupted during bright sunny days, of which Karachi gets more than 300 of every year.

The largest, most profitable of K-Electric’s customers are also ones who are most likely to start generating their own electricity for a substantial portion of the day and even selling electricity back to the utility, a phenomenon known as distributed generation.

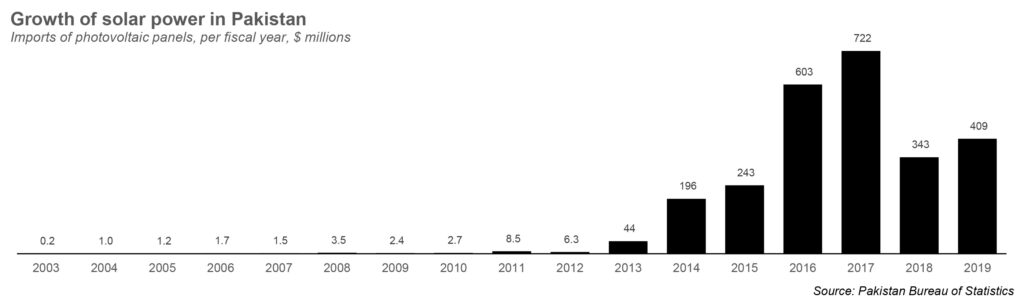

It may be tempting to think of solar power as a niche product, but that would be a tremendous mistake. The numbers suggest that the market is growing incredibly rapidly. Solar panels are not manufactured in Pakistan and are imported mostly from China.

According to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the value of solar panels imported into Pakistan in 2005 was just $1.6 million. The number for 2019? $409 million. That is an compound annual growth rate of 60.5%, astounding by any measure. Solar power in Pakistan is rapidly gaining traction.

As more of the wealthier consumers – both domestic and industrial – shift to alternative energy, K-Electric will be left with the smaller, less profitable customers, typically in areas with theft rates that can often be up to four times higher than in the more affluent neighbourhooods.

Not only would its addressable market shrink, but the utility would be left with the most bothersome portions of its customer base.

Of course, it does not all have to be doom and gloom. For one thing, distributed generation is growing slower than it could be in large part due to a lack of consumer financing. Any management team with its salt would recognise the opportunity to provide that financing in exchange for favourable power purchase agreements with industrial and upper middle class consumers looking to install solar panels on their rooftop.

This would require a utility company to start acting more like a consumer finance company, but the reorientation of business model is at this point completely unavoidable.

K-Electric’s approach until now, however, has been to oppose – or at least delay – this inevitability as much as possible. At least until now.

With the launch of a venture capital fund dedicated towards renewable energy – and with a specific mention in the investment mandate to include distributed generation – K-Electric’s management might be signaling a shift in approach to the market. Or are they?

The miniscule amount allocated towards distributed generation suggests that the company is either not serious about this initiative, or at the very least not convinced enough to make a more substantial investment into the project. It has not yet announced any details about what its investments in this space might be, and whether it will be funding entrepreneurs in this space or whether it wants to fund internal pilot projects through this initiative.

So what can outside observers make of this initiative? It is clear that at the very least K-Electric’s management is publicly admitting that distributed generation is here to stay, and will likely significantly shake up the electricity industry in Pakistan.

The more charitable explanation for why the company is investing so little in the space? They are not yet sure what direction the market will take and want to experiment with a few different approaches before they make a decision that will likely have profound impact on their overall business model.

That caution may well be the right approach. But it also suggests an unwillingness to take bold risks at a time of massive transformation in the industry, with the government finally beginning to deregulate the energy market and allowing power generation companies to sell to entities other than the state-owned electricity transmission company.

Add in the fact that solar electricity is now becoming so common that solar panels get advertised on the nightly news and banks are starting to offer financing to well-qualified buyers, and distributed generation is a reality that the utilities like K-Electric need to get comfortable with, and fast.

The sooner they can pick a strategic direction and run with it, the better. They may no longer have much time left for experimentation.