Malik Riaz’s stint as a banker has come to an end with Escorts Investment Bank going up for sale. The stint lasted for four years. Malik Riaz’s banking career came to life in 2017, when he bought the Escorts Investment Bank. Originally, the real estate tycoon had wanted to buy Burj Bank. However, his attempt to buy this small but traditional commercial bank had been blocked by the State Bank of Pakistan. For reasons we will explain later, a traditional commercial bank would have been much better for his attempt at revamping Pakistan’s nearly non-existent mortgage market.

The failure of Malik Riaz is a rare occurrence. In his 20 years as a real estate developer, he has proven himself to be ruthless in his pursuit of expansion, and intuitive in his understanding of what people want. That is why in 2017, he bought the Escort Investment Bank for a grand total or one rupee. The acquisition was a piece of news that had everyone scratching their heads. Why would Malik Riaz want to buy a bank, and if it was to be able to offer people financing for his housing projects, wouldn’t he want to buy a commercial bank? Back then, Profit had covered Malik Riaz’s purchase of Escort Investment Bank, and in a vividly crafted story, this magazine’s managing editor, Farooq Tirmizi, explained why Malik Riaz would want to buy an investment bank in the first place and why it was bound to fail. Today, Profit has reliable news that the bank is up for sale but has no buyers – because it is in such an undesirable state.

So what did Malik Riaz do with the bank and why did he fail? Was he set out for failure from the very beginning or did something else go awry? This is a Profit obituary on Malik Riaz’s failed stint as a banker, and what the fallout of this failure could be on the ‘successful’ branding that Malik Riaz and Bahria Town rely on.

The Bahria Town concept

There is one and only one real cultural estimation of whether you have ‘made it’ in Pakistan – and that measure is whether veteran journalist Sohail Warraich has ever called you up and asked to film an ‘Aik Din Geo Kai Saath’ episode with you. A seemingly unassuming, gentlemanly, even oafish presence, Warraich is beneath the surface a master interviewer that can shrewdly get powerful men and women to spill their secrets, and bring out the private personalities of those that otherwise maintain very stoic media profiles out of necessity.

In one such interview with Malik Riaz, Warraich got him to spill his secrets on what the trick behind making Bahria Town so successful was. In a moment of journalistic mastery, Warraich asked Malik Riaz a number of lighthearted questions to soften him up, before throwing a pointed question about the European inspiration behind his housing projects. “We go to foreign countries, we see what they have done, we steal the idea and we bring it here,” Riaz responds with shocking candour. “That is all there is. Like I just saw the Eiffel Tower recently, so we imported a replica from China and everyone loves it and comes to Bahria Town from far away to see it.”

This little tidbit reveals a much darker side of how real estate developers hook in people for their housing schemes. How they prey on the most basic, the most earnest, the most common of desires that anyone of a middle class background in this country will be able to understand – to live respectably in a home of one’s own. A ‘plot’ (pee-lat) in Pakistan is sacred. The desire to live in a clean, gated, ‘posh’ area is the upper-middle class dream for most Pakistanis, one that they spend their entire lives at times, trying to achieve.

Every year, the urban housing demand in Pakistan is 350,000 homes. Of this, 62 per cent is for lower-income groups, 25 per cent for lower middle- income groups, and 10 per cent for higher and upper middle-income groups. The formal supply per year is 150,000 units, a disproportionate amount of which caters to the higher and middle-income groups. It is this desire to own a home, to live with dignity in security, and to have facilities that the government should but is unable to provide is what Malik Riaz has tapped into over the past two decades.

But with real incomes falling fast, there are now fewer people than ever that are able to afford a plot of land outright. Salaried classes find it harder to save with regularity now, which is why it is so difficult for them to pay a lump sum. If, however, mortgages were available and people could pay over time in installments, there would be a lot more people lining up to try and get possession of these plots. Besides, it is much better for some to pay in bits and pieces and acquire the place at the age of 30 rather than having to save their entire lives to buy a home outright after retirement. That is why Malik Riaz bought the bank and took the gamble – one that didn’t pay off on this occasion.

Always on the cards

The feeling of being able to say ‘we told you so’ is one that we do not revel in, but it is still a pleasant feeling to be able to say that what we predicted happened. “This transaction does not have a snowball’s chance in hell of working out,” were the exact words from the previous article. The reasoning was simple. Bahria Town was the wrong company to try to revolutionise mortgage lending in Pakistan, having absolutely no experience in consumer finance in the past. An investment bank was far from an ideal instrument to select in order to embark on a mortgage lending spree. And even if it was, Escorts was far from the best institution to pull it off. It had neither the capital, nor the talent, nor the relationships to be the kind of innovative institution that Bahria Town would need it to be for this experiment to work. Today, the experiment has failed and Bahria Town seems ready to accept that it has.

Sources have informed Profit that not only is the bank up for sale – it is having a hard time finding any buyers. That makes sense, because even four years ago when Malik Riaz first bought Escort, it was in shambles and four years of trying to turn it into something better has not worked out or even made it a slightly attractive buy.

The reasons for why Escort Investment Bank was a bad buy, why Malik Riaz went ahead with it anyways, and why it was never going to work out have already been detailed by Profit in the earlier mentioned feature titled ‘What is Malik Riaz up to now?’ that we would encourage everyone to read or even re-read. It contains not just hard financial analysis of why the idea was a bad one, but also details of the corporate history of Bahria Town and the strategies with which Malik Riaz operates. For those that do not want to, here is a very brief summary of what happened:

Pakistan has a horrible mortgage market that is not friendly towards upper middle class prospective homeowners and does not provide home financing. With the buying power of the middle class shrinking, Malik Riaz realised that new customers of Bahria Town homes would need financing, and since the banks were not ready to do this for Bahria Town, Malik Riaz would take matters into his own hands and buy his own bank. To do this, he made a bid to buy the country’s smallest bank – Burj Bank. Unfortunately for him, the State Bank of Pakistan had other ideas. The SBP worried that Bahria Town and Malik Riaz were not the kind of people it wanted to entrust with retail deposits from the general public. Undeterred by this very public snub, Malik Riaz turned his attention towards Escorts Investment Bank. On February 8, 2017, Bahria Town announced its intention to acquire Escorts from the family-owned business group that controlled over 71% of its shares for a single rupee. The deal went through, and Malik Riaz now had a financial institution that would be able to offer prospective Bahria Town buyers financing. The problem was that an investment bank was a horrible vehicle for this, and Escort Investment Bank was the worst among such banks to take on the task.

Here is what happened

Malik Riaz’s idea was that once he had the investment back behind him, it would encourage more buyers to buy Bahria Town property. The problem was that the bank was unable to lend at competitive rates due to its low levels of deposits and losses. In addition to that, the bank also has competition from the Government’s initiative for housing finance. With such cheap credit available, who would pay two times the interest rates for property in Bahria Town, especially following the controversies associated with it.

That, however, does not mean Bahria Town did not at least try to turn the bank around, because that was what they had to do first and foremost to have any chance of making something out of the investment. “The company is a listed financial institution. You will hear of it through the PSX if there is any such news,” says Naveed Amin, the CEO of the bank. A company man, Naveed naturally denies the news but not without a caveat adding later that “with things like these you never know what can happen in the future.”

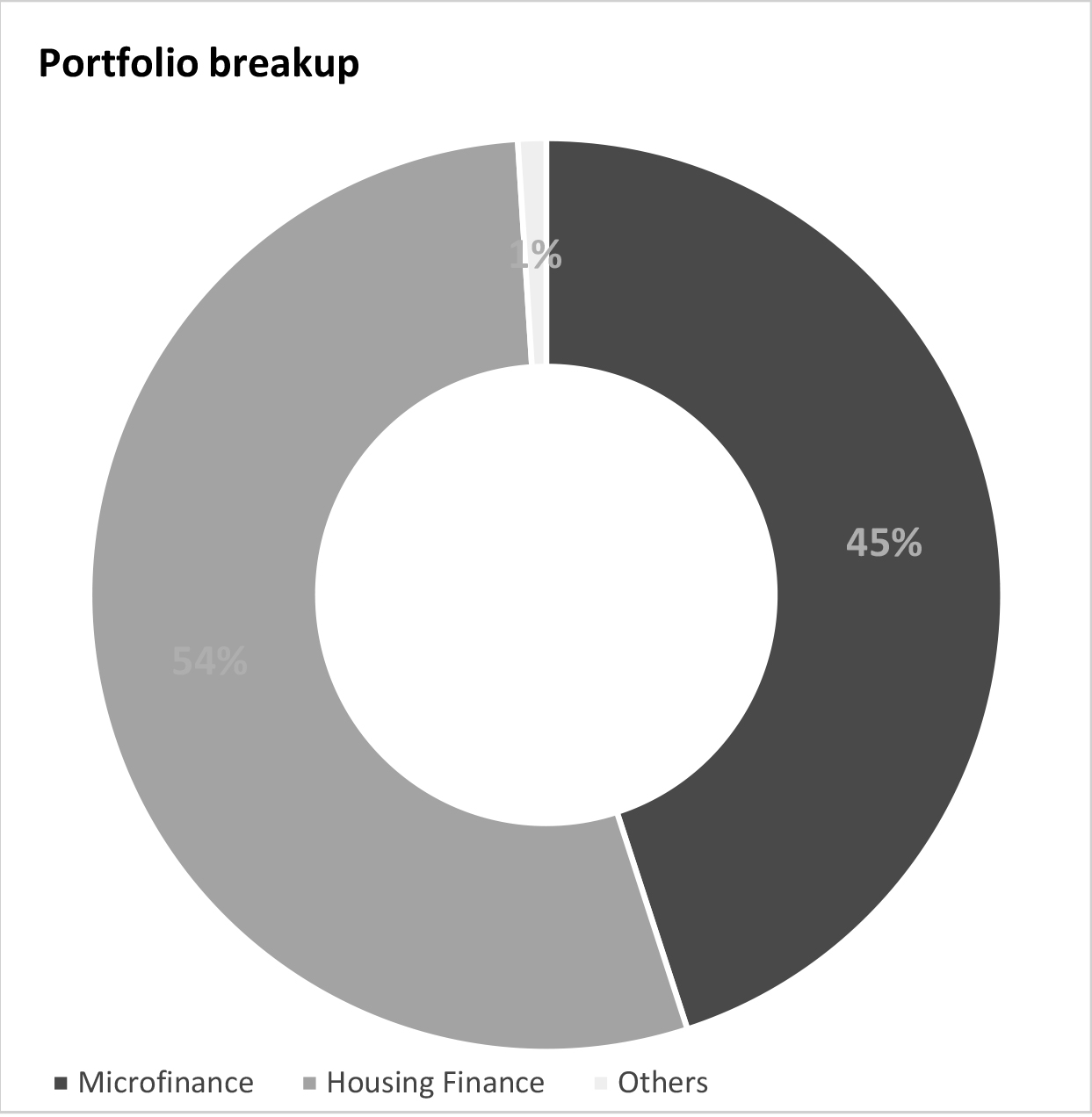

The almost clear admission of the standing of the investment bank was followed by long winding defenses, and to be fair, the bank really did try to shake itself out of its horrific run and turn things around. Following Riaz’s takeover of the bank, a lot of restructuring did take place. In addition to housing finance, Riaz decided to introduce micro financing opportunities for shops in Bahria town and other areas. However, last year when COVID hit, the implementation of the project got impacted. Amin states that they did not stop business during COVID but focused on survival, keeping the portfolio intact, and avoiding bad debts. The bank however shifted its gear towards the short and medium term instead of long term. Housing finance is generally long term. Currently, an analysis of the finance portfolio shows that 150 million, or 54% makes up the housing finance, whereas 45% through microfinance. Last year this was at 56% and 40% respectively.

“It was a bankrupt bank when they bought it. Half the reason for selling it for a single rupee was so that they could get rid of some of their bad debts and liabilities,” explains Amin. “When Bahria stepped in, they made changes to turn the bank around by 180 degrees. We had a commitment with the regulator. We made payments to all old depositors and paid off liabilities. Within a month of the takeover, we had paid around Rs 532 billion.”

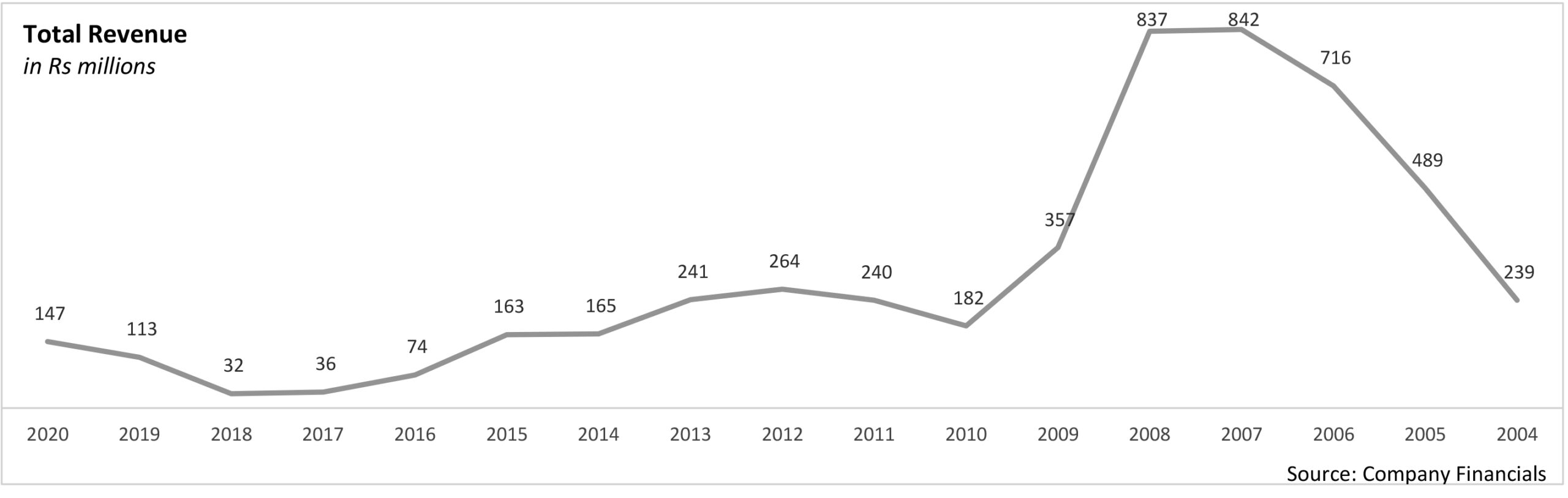

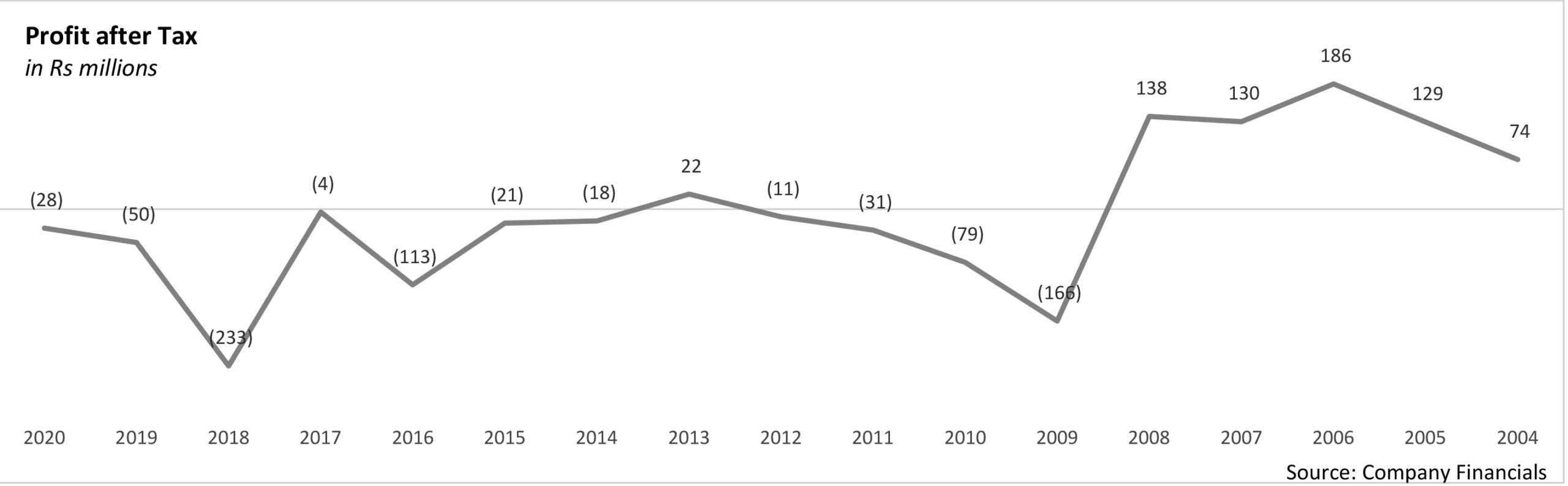

If we talk about the company’s financial position, Escorts Investment Bank has been largely making losses over the past decade with an exception in 2013. The revenue of the bank has largely remained flat over the decade. Following the acquisition, however, Escorts Investment Bank has been able to manage its profit after tax and bring that to a small number with a small rise in revenue too. To say that things are heading towards stability, if not profit, could be a safe statement. Unfortunately for Bahria Town, this is not what was required to help in financing Bahria Town property, and with stability still not guaranteed, providing expensive financing has not turned out well either for the bank or for Bahria Town. And more importantly, it has not improved enough for the bank to be desirable, since no sellers seem to be presenting themselves to take the bank off Malik Riaz’s hands.

In the right circumstances, the bank could have been a good idea.Had things gone to plan, Riaz may have been able to bolster Bahria Town sales and make a dime off it too. Pakistan currently faces a housing deficit. You wouldn’t think of that considering the number of housing projects you see being made. The housing demand itself is growing by around 700,000 houses per year. The bulk of which are for the middle and lower income segment.

Very few houses are actually financed through banks or formal lending financial institutions. It’s usually personal savings that go towards buying property. Had Riaz been able to tap into this segment, not only would he be able to sell houses in Bahria, have a base to expand the projects, but also be able to earn off the financing. Escorts provides 100% construction cost loans to people that already own plots of land. Loans are also given to non-resident Pakistanis. Considering Bahria Town is their own project, the time to get financing and carry out paperwork is also less than what you would face regularly.

Unfortunately for Malik Riaz, despite all of the desperate attempts to stop the rot, the bank’s finances are a brutal picture. Picking any commercial bank for the task of revolutionising Pakistan’s mortgage system would have been like picking a horse for a race – a discerning eye would have been required to assess which horse would best perform in the given circumstances. In Malik Riaz’s case, the choice of Escort Investment Bank was the equivalent of picking a Llama for a horse race – in its own right a Llama can run pretty fast, but not as fast as a horse and you really can’t expect it to carry you. And to make things worse, Malik Riaz picked the oldest, shabbiest, most underperforming Llama there was. At the end of the day, you do get what you paid for, and this is what you get in one rupee. Instead of the Goliath financing provider it was supposed to have become, Escort has improved with the added investment, but is not just the wrong bank to come through on this experiment, but also the wrong kind of bank.

The image issue

One thing that we must admit about Malik Riaz is that he is an astute businessman. He is not afraid to use whatever means are at his disposal, and has on occasion admitted to bribing government and public officials to get his way about things. And if there is one thing about Malik Riaz, it is that he recognises when something is going right or wrong. Perhaps that is why he is so quick to get rid of the bank he had such high hopes for. Escort was a bad decision, and that for Malik Riaz is a failure. Unfortunately for him, his entire thing is being successful and his rags to riches story. Already Bahria Town has started to get a bad reputation in property buying circles for being in the limelight for all the wrong reasons. And with this failure soon to become public knowledge, it could be another blow to the Bahria Town, and indeed, Malik Riaz image of success.

A long time ago at a dinner party filled to the brim with the elite of this city, a friend of one of the editors of this magazine was introduced by another friend to a gentleman that was not particularly impressive to look at. The friend chatted over the gentleman who stood by amicably listening to the conversation between the two men that knew each other. At one point, he turned around and asked the gentleman, “and what do you do?”

“I’m a banker” came the response.

The man in question was back then not very well known by face because his pictures had not yet gone out to the media – but he was not a banker, he was merely the owner of a bank and in reality an industrialist, and one of the richest men in Pakistan back then and to this day. Yet when someone asked him what he did, he responded by saying he was a banker. That is the sort of respectability that the profession commands – and among the elite, there is a certain pride in having made money through the world of finance rather than business. So for Malik Riaz, to fail owning a bank is a particularly stinging rebuttal of his status as the ‘it’ man of Pakistani business. If you can’t own a bank and run it well, would people still aspire to be you? The question is an open-ended one, but it will be bothering Malik Riaz even now.

At the end of the day, both the bank and Bahria Town have become issues of credibility for Malik Riaz. For starters, the initial reason why commercial banks were refusing to provide financing for Bahria Town property was that banks require clean, undisputed titles of land ownership for any house/flat they finance and the land titles of Bahria Town properties are not as clean and transparent as they appear to the general public. With continued litigation against Bahria Town, allegations of personal corruption against Malik Riaz, and a general mistrust of the housing projects means that unless perfect financing conditions were being provided by Escort, people were not going to bite.

Malik Riaz and Bahria Town have a serious image issue on their hands. As we have repeatedly said not just in this story but in the many stories Profit has done on real estate in Pakistan – Malik Riaz and others make money on the very precarious dreams of Pakistan’s middle classes to have a home of their own. For so many people, buying a plot and building a home on it is not just the most money they will ever spend on a single thing in their lives, but it is also possibly the most important decision they make in their entire lives. Where one has a house determines what school their children go to, how much inheritance they leave behind, and even what possible matches for marriage their children get. When making a decision that big, it would take the truly brave of heart to invest in a place that is considered shady or where dealings are not necessarily always thought to be above board.

this content is appreciable <3

Awesome article on the greatest conman of Pakistan.

What Is a Dead Load

keyed pointing