Samba Bank is up for sale, and the buyers are lining up waving cash in hand trying to get their hands on the bank. Why are there so many contenders to buy out the smallest commercial bank in Pakistan? For starters, it is a nice, clean, well-run operation. The other reason is that banks are hard to come by for people in the market shopping for one.

Back in 2018, three major banks went up for sale. This was a first in Pakistan’s banking history,a and the news was broken in these very pages back then and did not bounce to the extent that the banks, namely Bank Alfalah, Meezan Bank, and Faysal Bank, were indeed on the market, but neither was actually sold to a new buyer and all three are still being run under the same ownership structure.

That even one of these banks would be up for sale, let alone three simultaneously, was strange to say the least as all three were doing quite well at the time, infact, thriving and growing in the individual space that they had created for themselves over the years.

So why didn’t they sell then? In one case, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) was not comfortable with any such transaction (more on that later) and in the others there was a realisation of ‘why fix it if it ain’t broke’, and all three corrected course.

But Samba going up for sale offers a unique opportunity to a number of different players licking their lips at the prospect. On the one hand there are two of Pakistan’s largest banks as claimants. The Fatima Group has also thrown its hat in the ring, and perhaps most interestingly at least one fintech startup has made its intentions known. Which of these players will be successful? Profit looks at how good of a deal Samba really is, and which potential buyer has the best chance to close the deal.

The tiny clean bank?

The origins of Samba go back to as early as 1955, when Citibank first established itself in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. However, it wasn’t until 1980 that the Saudi American Bank (Samba) was formed as the result of a change in the law which required all foreign banks to be at least 60% Saudi owned.

Samba continued to grow, expanding its international presence by entering the United Kingdom in 1984, and creating one of the largest financial institutions in the Middle East after a merger with United Saudi Bank in 1999.

By 2004, Citibank had sold all of its remaining shareholding to local investors, making the Samba Financial Group a wholly Saudi owned subsidiary, looking to expand internationally. In 2007, Pakistan did not seem like a bad place to be, with other foreign banks such as RBS and Barclays entering the market the same year. Samba bought a majority stake in a fledgling 5-year old Crescent Commercial Bank and began operations.

Looking at its growth trajectory, it seems there was never any real ambition to grow fast and grow exponentially. The focus remained on continuing to build a stable bank with a small to medium sized presence in all aspects of commercial banking. It is therefore a pretty boring bank to look at, one that is content with its size and low risk appetite.

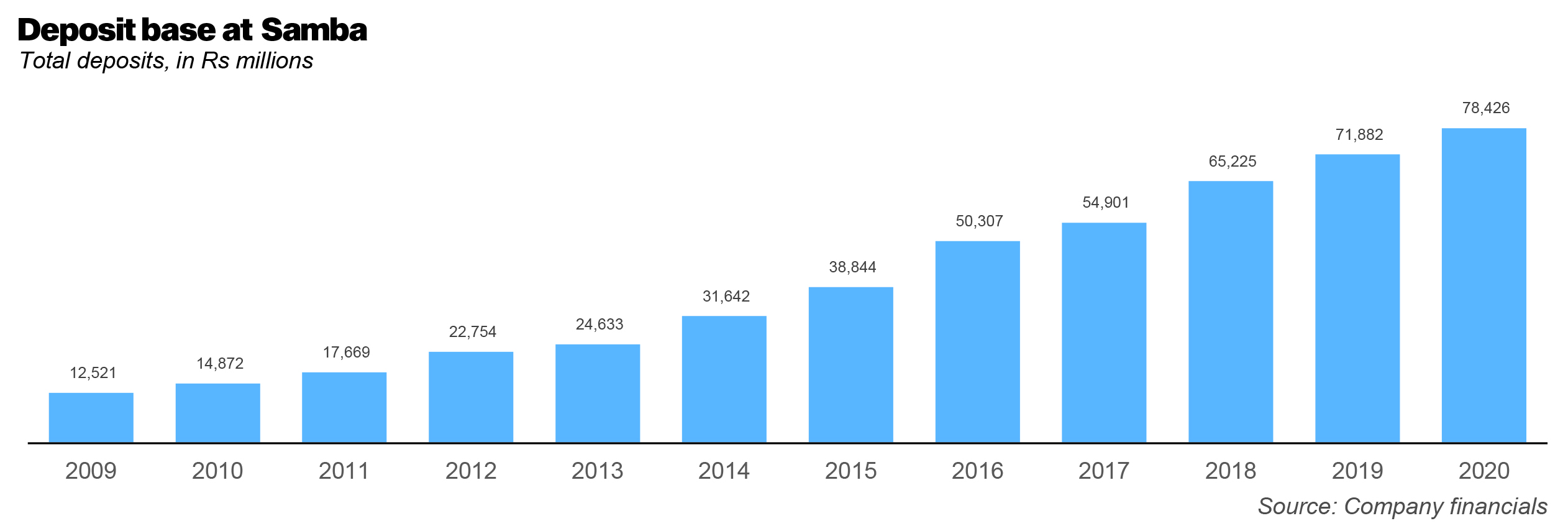

This is further evidenced by the fact that Samba has also avoided building too big a branch network, adding only 10 branches in the past 10 years to bring the total to 40. It is then no wonder its market share in terms of deposit size has remained between 0.3%-0.5% over the past eleven years, the lowest in the industry. At the same time however, although the deposit base is small, its 5-year CAGR for deposits is an impressive 15.9% compared to the industry’s 5-year CAGR of 13.9%.

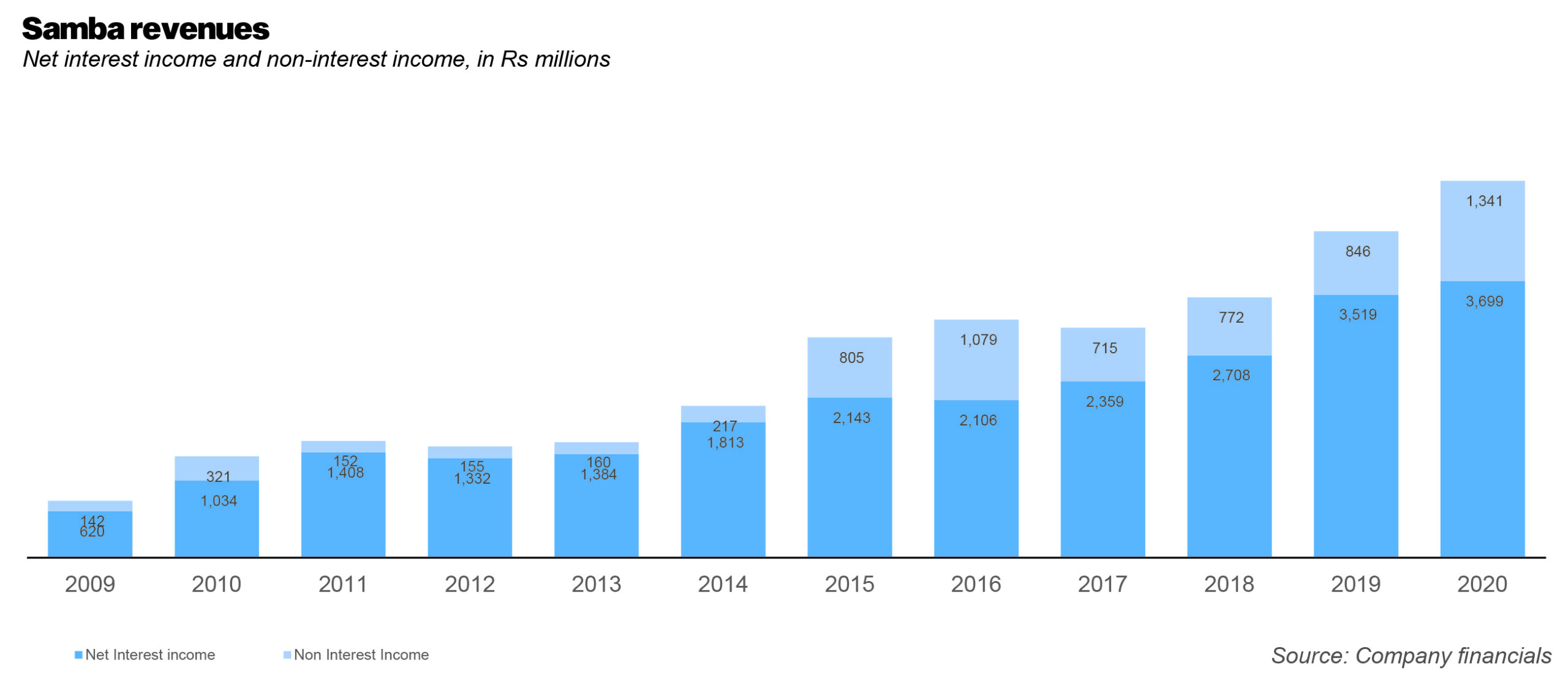

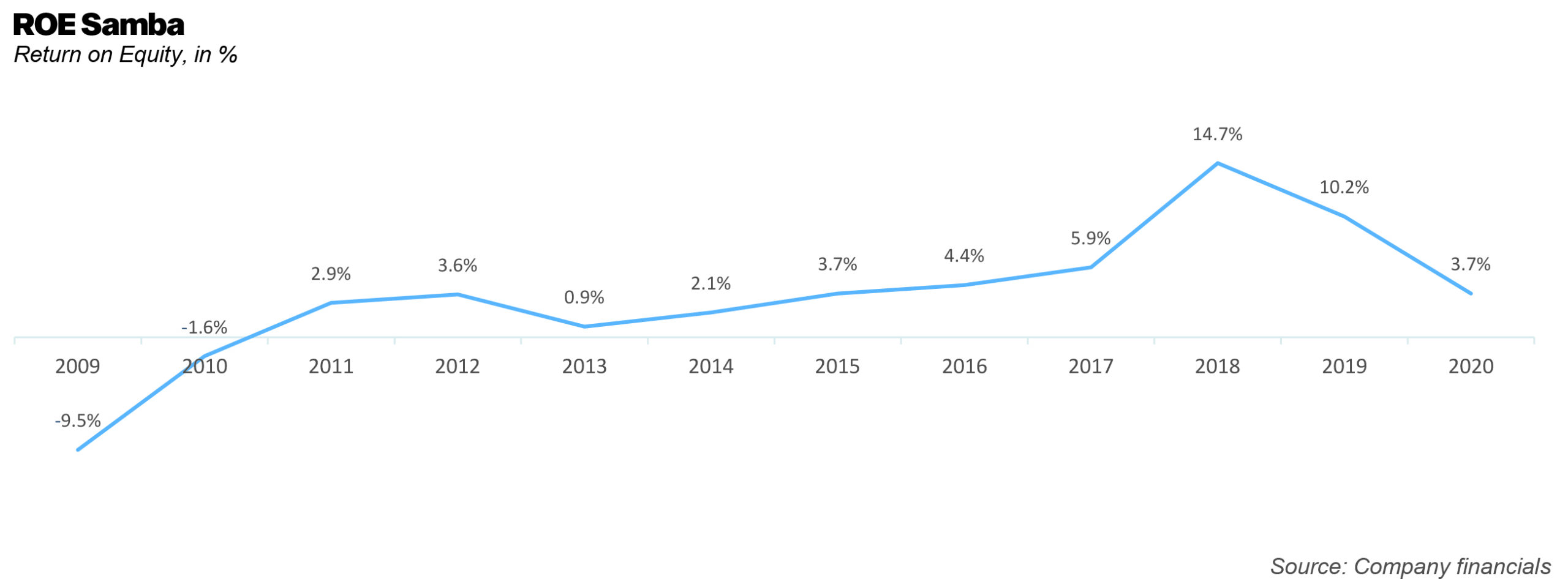

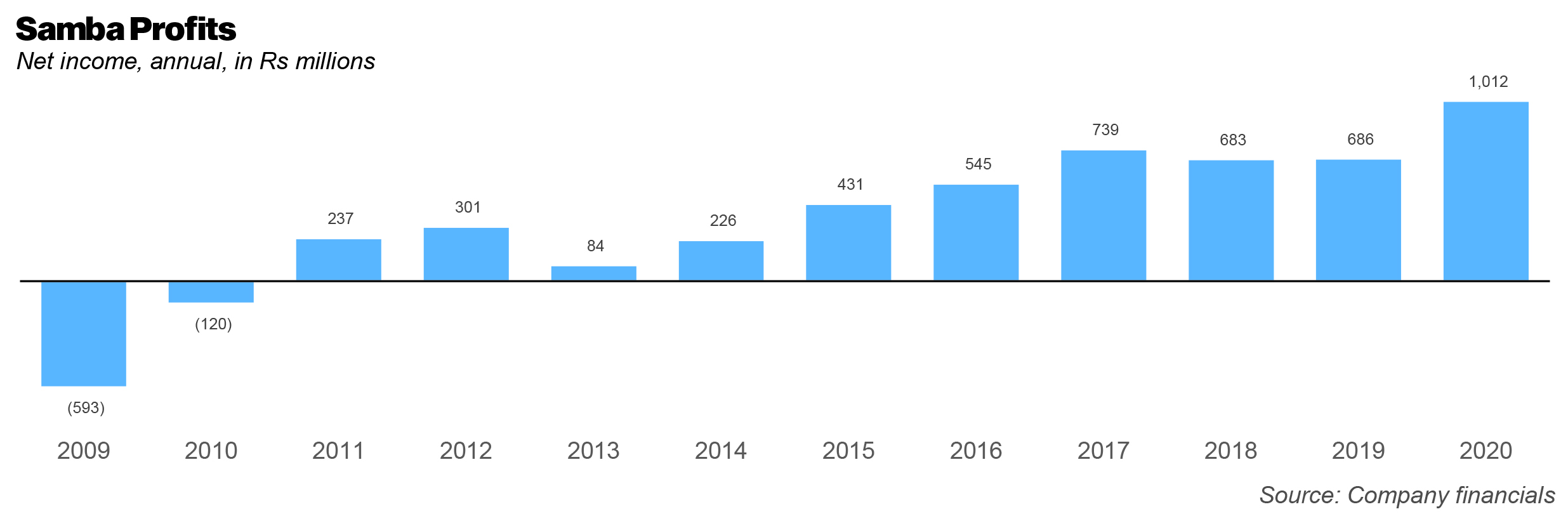

As far as revenue and profitability are concerned, there is healthy growth, with the 5-year CAGR for gross income (interest plus non-interest income) at an acceptable 11.32% while 5-year CAGR for net profit after taxation stands at a comfortable 18.62%.

Apart from the financials and size, the bank is not at all politically indulged, which is an attractive characteristic for any bank that is up for sale in Pakistan, as it reduces the likelihood of discovering dirt at later stages of a deal. Summit Bank is one such example, which was accused of laundering money for ex-president Asif Ali Zardari.

There are, however, some questions that arose during our research into Samba, answers for which were not given. To begin with, there is a key indicator of health that is missing in the balance sheet 2012 onwards, the much looked at Non-Performing Loans, figure. Up until 2012 It is listed in the ‘other information section’, but in the following 7 annual reports, it is either excluded, or at least presented in a way that is hard to understand. Profit reached out to the bank’s CFO for some clarity on the matter but was unable to get an answer.

Secondly, there is the matter of Punjab Beverages Company Private Limited, a major bottler for Pepsi in Punjab and a key corporate client at Samba. According to market sources this relationship turned messy recently when ‘bank guarantees’ Samba had provided on behalf of its client were called up. ‘Bank guarantees’ are off-balance sheet allowances made to clients and therefore do not show up in published financial statements.

For clarification, Profit reached out to Corporate Business Head Central and North Ali Raza Syed. He explained that the account had been transferred to Special Assets Management (SAM) Group, meaning it had been classified as an irregular account by the Bank. Profit was unable to reach Samba’s Group Head Legal Affairs, Zia Shamsi, who according to Syed is currently overseeing the matter. Therefore, it is safe to say that while largely clean, some problems may be highlighted when it comes to the due diligence stage.

Why sell?

If Samba is so financially stable, runs a relatively tight ship and is also profitable, why is it being sold? Profit tried to get the Bank’s perspective on this key question but to no avail. Alternatively, we took a look at a recent major development with regards to the ownership of the bank to try and understand the sale.

Back in April of this year, Saudi Arabia’s largest corporate lender National Commercial Bank (NCB), successfully merged with Samba Financial Group to become the kingdom’s biggest bank with an asset base of $239 billion. The move fits in with its consolidation strategy as well.

Eight months later, the NCB has decided to pack up its Pakistan operations and for good reason. To begin with, Samba Pakistan is merely a speck in NCB’s portfolio that does not generate a lot of revenue.

In order to maintain its operations here, no matter how small, it has to allocate some capital, capital it could use elsewhere more efficiently. Following the financial crash of 2008, ‘basel 3’ was formed, a regulatory framework that sets and monitors global minimum capital standards for commercial banks. According to one senior banker, the minimum liquidity requirement relative to Pakistan would roughly translate into NCB deploying an extra $1 to cover each dollar of capital it has parked with Samba Pakistan.

The new ownership does not view this as a viable cost to do business in Pakistan where it would take a tonne of more capital to grow in size and make more money. It just doesn’t make sense. Another consideration for a foreing financial group investing in Pakistan is the dearth of foreign banks left in the country, with practically only Standard Chartered Bank qualifying as one with a considerable presence and scale of operations.Others, such as Citibank and Deutsche operate on a very miniscule scale and specialised manner.

The potential buyers

Fatima Group:

The contender who is the farthest along in the bid for Samba is one of the largest business conglomerates in the country with interests in fertiliser, energy, textile and sugar.

According to official documents, FFCL is making the bid as part of a consortium that also includes the current management of Samba Bank represented by its current CEO, Shahid Sattar and Gulf Islamic Investments LLC, looking to acquire up to 84.51% of shares of the bank.

Additionally, Arif Habib, CEO of Arif Habib Corporation Limited who is also the chairman of FatimaFert Limited, a subsidiary of Fatima Group, is also representing FFCL, which is why, naturally Arif Habib Limited will be the manager of the transaction.

FFCL is perhaps the strongest of the contenders with a mega business conglomerate at its back. According to some industry experts however, Fatima Group, other than its fertilising arm FFCL, has had trouble making its other businesses big success stories. Its energy interest, for example, struggled to take off and has recently secured long-term restructuring for a facility it availed from a consortium of banks.

To understand the intentions of the sponsors of Fatima group, or for that matter any big Pakistani business group in pursuing a bank can be understood through an anecdote. Many years ago at a dinner party filled to the brim with the elite of this city, a friend of the Publishing Editor of this magazine was introduced to a gentleman that was not particularly impressive to look at. As is customary in such parties, the friend asked him, “and what do you do?”

“I’m a banker” came the response.

The man in question was back then not very well known by face because his pictures had not yet gone out to the media – but he was not a banker. Yes, he owned a bank, but in reality he was an industrialist, and one of the richest men in Pakistan back then and to this day. Yet when someone asked him what he did, he responded by saying he was a banker. That is the sort of respectability that the profession commands – and among the elite, there is a certain pride in having made money through the world of finance rather than business.

The bid by FFCL will therefore be purely to get a commercial banking licence and enter the banking sector. It will most likely try to grow Samba larger than its current size with adequate capital injection to become a more competitive bank.

That it has a Shariah compliant Gulf-based financial advisory firm in Gulf Islamic Investments LLC indicates that there is perhaps an Islamic Banking angle to the acquisition. As a subsidiary of GII Holding group (GII), with international presence in major markets, it brings a lot to the table.

The inclusion of a foreign buyer in the consortium also addresses the SBP’s concern about capital leaving the country as it allows FFCL to arrange the payment outside of Pakistan, via UAE to Saudi Arabia. The investment into the newly bought bank would then be generated locally.

TAG

The underdog in the running also happens to be the best suited to procure Samba. TAG, abbreviation for Talal Ahmad Gondal, the CEO of the fintech startup looking to become Pakistan’s first digital bank, is perfectly placed to take advantage of Samba’s availability on the market.

Although it already has an in-principle approval for the Electronic Money Institution (EMI) license to operate as a digital wallet from the SBP, TAG’s ambitions are larger, as it wants a seat at the big boys’ table, the commercial banking sector.

Why does TAG desperately want a commercial banking licence when it has an EMI license? Well, an EMI license has limitations that a conventional commercial banking license does not. EMIs are outrightly banned from paying an interest rate to depositors. While EMIs are allowed to invest deposits into government bonds, it is limited to 50% of the previous three months’ balance, and with their higher capital requirements than banks, this means they can realistically invest much less of their deposits than banks.

Then there are restrictions on customers as well. In terms of putting money into their digital wallet, the cap is Rs 50,000 in a month, which can be increased to Rs 200,000 provided the wallet holder has completed biometric verification. As far as withdrawals are concerned, the limit is Rs 10,000 per day, no matter what level of authentication has been completed. For commercial banks, once biometric verification of a client is done, there is virtually no limit on deposits or withdrawals.

Upgraded versions of an EMI license that SBP also offers are Digital Retail Bank (DRB) and Digital Full Bank (DFB) licenses. A DRB can perform all regular banking functions but cannot tend to corporate clients. A DFB can serve all categories of clients but cannot have a physical branch network. For EMIs to get a DRB or DFB license is no easy task either.

EMIs therefore simply cannot compete with conventional banks. For TAG, getting Samba’s commercial banking license by purchasing the bank is the quickest and cleanest way to enter and disrupt the commercial banking sector.T

That it is funded by venture capitalist firms such as New York-based Liberty City Ventures and Banana Capital is a plus for TAG, for it can easily arrange to pay NCB for Samba outside of Pakistan, thereby removing SBP’s apprehensions about capital leaving the country. Infact, in all likelihood, the initial cash injection that will be required to take Samba to the next stage, that some market experts put at around $50 million, will translate into much-needed FDI for the country. It is therefore a win-win for the central bank.

However, TAG’s obvious advantage to be able to raise capital abroad is partially trumped by its credibility problem. To begin with, there is the debatable $100 million valuation that Profit has extensively covered and explained already . Then there is the composition of the board that is problematic. Talal, who was able to get SBP to approve his company’s EMI license in a matter of months while it took others well over a year, is politically connected.

Additionally, it has on its leadership team a former general of the Pakistan army who was head of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) (Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, erroneously mentioned the former general as a board member and a comment on his connection with a Supreme Court suo moto notice. Even though on TAG’s website, the former general is mentioned as chairman, it seems to be an operational title only. This is also evident from the SECP records, according to which the only two directors of the company are Talal Ahmad Gondal and a Tayyab Kaleem Khan. The error is regretted.)

Meezan Bank

The country’s largest Islamic bank was in the running to procure Samba Bank. Speaking to Profit Meezan’s CEO, Irfan Siddiqui confirmed that it had submitted an initial non-binding offer to Samba’s auditor’s KPMG Pakistan.

“We were very interested in Samba but our initial bid, which is the first step before approaching SBP for approval to begin due diligence, was too low so we are out of the running”, explained Siddiqui. ”We felt Samba is a clean bank that would add something extra to our balance sheet while helping us expand our branch network and corporate client portfolio as well”.

Meezan’s un-audited deposits as of September 30, 2021 are Rs 1.34 trillion while Samba’s are Rs 86.7 billion for the same period. Samba would have therefore increased Meezan’s deposits by 6.45% if a deal was made, hardly a significant bump, which would somewhat explain why Meezan’s initial non-binding offer was on the lower side.

Meezan Bank has previously made two successful acquisitions in Pakistan. It bought Societe Generale Group in 2002 for its commercial banking licence. Later in 2015 it acquired HSBC Oman that provided the growing bank with better systems and some valuable human resources.

UBL

According to Market sources, United Bank Limited (UBL) is also interested in Samba. At time of writing UBL was yet to confirm or deny this to Profit. Whatever the case may be, it is difficult to understand why a bank the size of UBL would be interested in a bank as small as Samba.

But why would one of the largest banks in Pakistan be interested in acquiring such a small bank? This begs another question: how does one grow a bank like UBL, that is already so big, with over Rs1.8 trillion in deposits?

For any business that reaches this stage, there are effectively two routes: grow market share through acquisition, or growth of the market itself. The latter being easier said than done.

The last time UBL showed interest in acquiring a bank was in 2012 when it’s request to conduct due diligence of HSBC’s Pakistan operations was turned down by SBP along with those made by HBL, ABL and MCB. The SBP had apparently used ‘too big to fail’ doctrine while rejecting these requests. After a decade UBL is going to try its luck once again.

One issue that would most definitely arise, would be resistance from the SBP, as there would be an outflow of capital, something the central bank ill-affords at the moment. In fact, this was the reason why Meezan had to take itself off the market in 2018.

UBL’s un-audited deposits as of September 30, 2021 are Rs 1.80 trillion while Samba’s are Rs 86.7 billion for the same period translating into a meagre 4.79% increase in UBL’s deposit base. Compared to Meezan, it would make even less sense for UBL to go for Samba, considering the negligible increase in deposits it would bring and an already impressive portfolio of corporate and SME clients that UBL has.

At the same time, UBL would have had to inject some capital into Samba’s operations to comply with SBP’s capital adequacy requirements, which it could easily manage internally as it is heavily capitalised. However, Samba would not be bringing much to the table for the amount of money UBL would have to invest. It does not seem likely that UBL would pursue this deal too far even if it is interested.

There are also reports that Askari Bank has also shown interest, however Profit was unable to verify this independently.

Who will take it?

Both TAG and Fatima group have approached the SBP for permission to begin due diligence of Samba. This is the first step in what is likely to be a long road for both entities to eventually acquire Samba. There are no guarantees that either TAG or FFCL will get this permission. For FFCL, a serious consideration for the central bank will be its somewhat problematic relationship with its bankers. As far as TAG is concerned, its profile and credibility will be under scrutiny. Samba’s ability to negotiate a good price will depend on how many buyers are able to secure the permission to begin due diligence and move onto the valuation and bidding process.

SAMBA Pakistan should only be acquired by a regulated banking institution. SBP should ensure that none of the industrial groups or family groups should be approved as a buyer. The Fintech candidate would also be a good choice. the three large banks HBL,MCB, Askari and Allied are already controlled by groups and or family groups.

I hope the SBP will use its “professional’ judgement.

Yousaf, am impressed with the in-depth details / reporting and an articulate writing. Appreciations!

In the corporate world though it may be business as usual to buy, sell and acquire companies, but what matters most is that it should be done professionally, objectively and on merit with due dligence. Hopefully, this process should be followed.