As you walk down the bustling streets of Karachi, the scorching sun mercilessly beats down on you, leaving you longing for a drink. Your eyes light up as you spot a nearby kiryana store. You ask for a bottle of chilled water. As you guzzle it down, you realise you forgot your wallet at home.

“No problem”, you say to yourself. Instead, you take out your phone and scan the QR code on the counter. Within a second, the shopkeeper’s account details appear on your screen and you enter the required amount. With a tap of your finger, you confirm the transaction and return your phone safely to your pocket. Your experience is so seamless and secure, that you prefer to pay by your phone, even though you have your wallet, the next time you are at a kiryana store.

As of today, however, you are unlikely to find yourself in this scenario. But if the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has their way it will be the future not just of Karachi but all of Pakistan. The central bank rolled out its payment system, Raast, all the way back in 2021. The hope was that Raast would be able to do in Pakistan what the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) was able to do across the border in India where QR payments in particular have become wildly popular and successful.

While Raast was not modelled off UPI, it was trying to permeate a very similar market. Like UPI, there were also high hopes for Raast. And after almost three years, Raast is finally about to enter its next stage which will define its success or failure. That’s right, Raast has finally deployed person-to-merchant payments (P2M). P2M payments refer to transactions where an individual customer (person) is able to make payments to a retailer/shopkeeper (merchant). This phase is the real test as it is where the mass consumers and retailers will interact with Raast payments on the ground.

You see if the Indian model is any indicator this is the make or break. It was P2M transactions in India that gave UPI its momentum. The widespread acceptance of digital payments in India largely hinges on the QR-based payment system, where even the smallest shopkeepers, like kiryana store owners or fruit stall vendors, facilitate and receive payments through QR codes. Could Raast potentially mirror UPI’s success? The answer lies not just in its forthcoming interaction with the masses, and the shopkeepers, but also in how the banks, fintechs and the banking regulator play their cards. Because while the markets are similar, the stories of the players dealing with Raast and UPI are very different.

What is Raast?

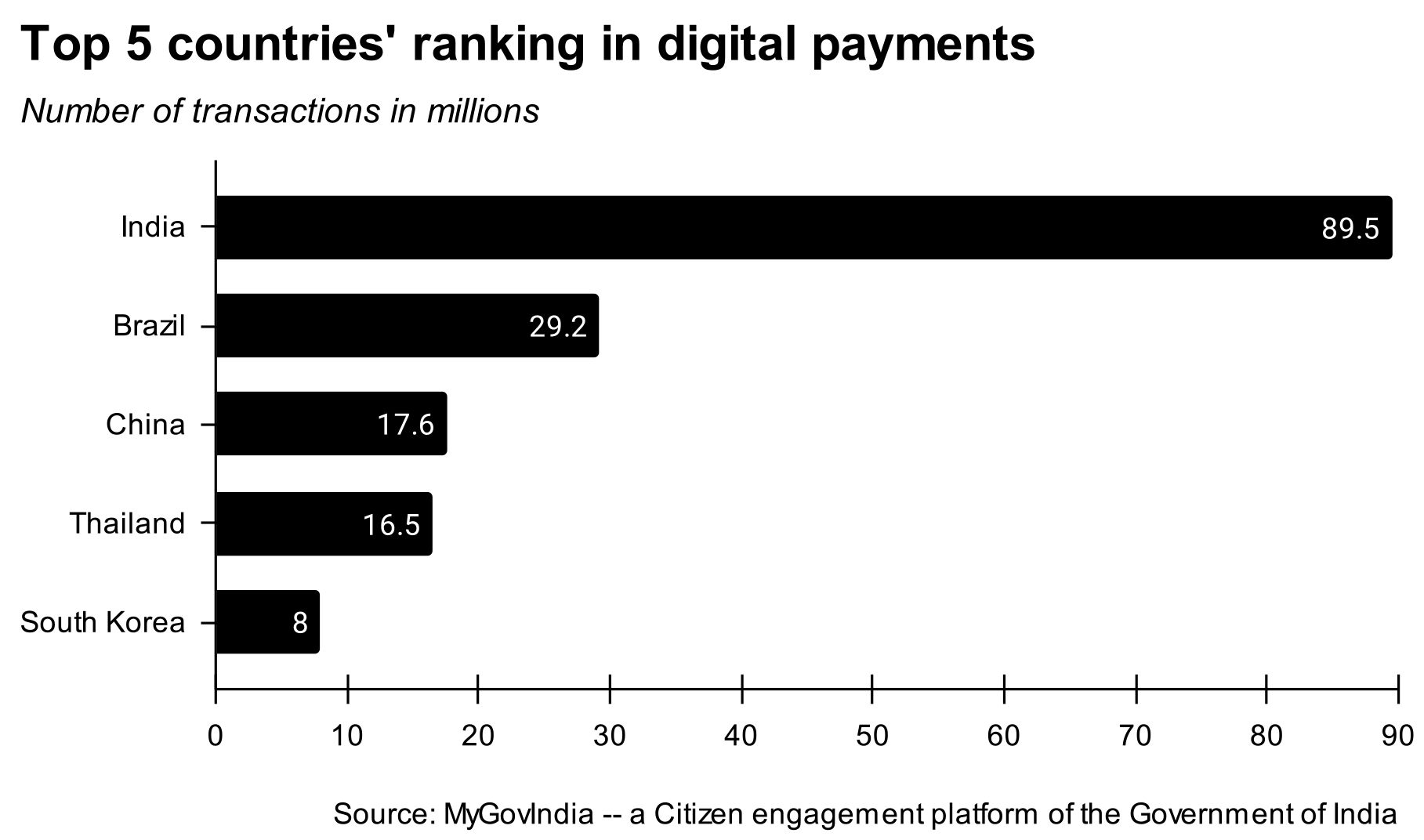

There is a lot that one can do with Raast. But very basically put, Raast is a back-end payments system that allows real-time settlement of transactions and makes them more instantaneous. The idea was to use it to fix Pakistan’s low digital payments penetration compared to other countries such as India or Brazil. There are a lot of reasons behind this such as banks relying heavily on expensive card-based payment schemes, the high cost of transactions and the unwillingness of ordinary citizens and businesses to digitise their daily transactions. What is relevant is Raast’s position in this.

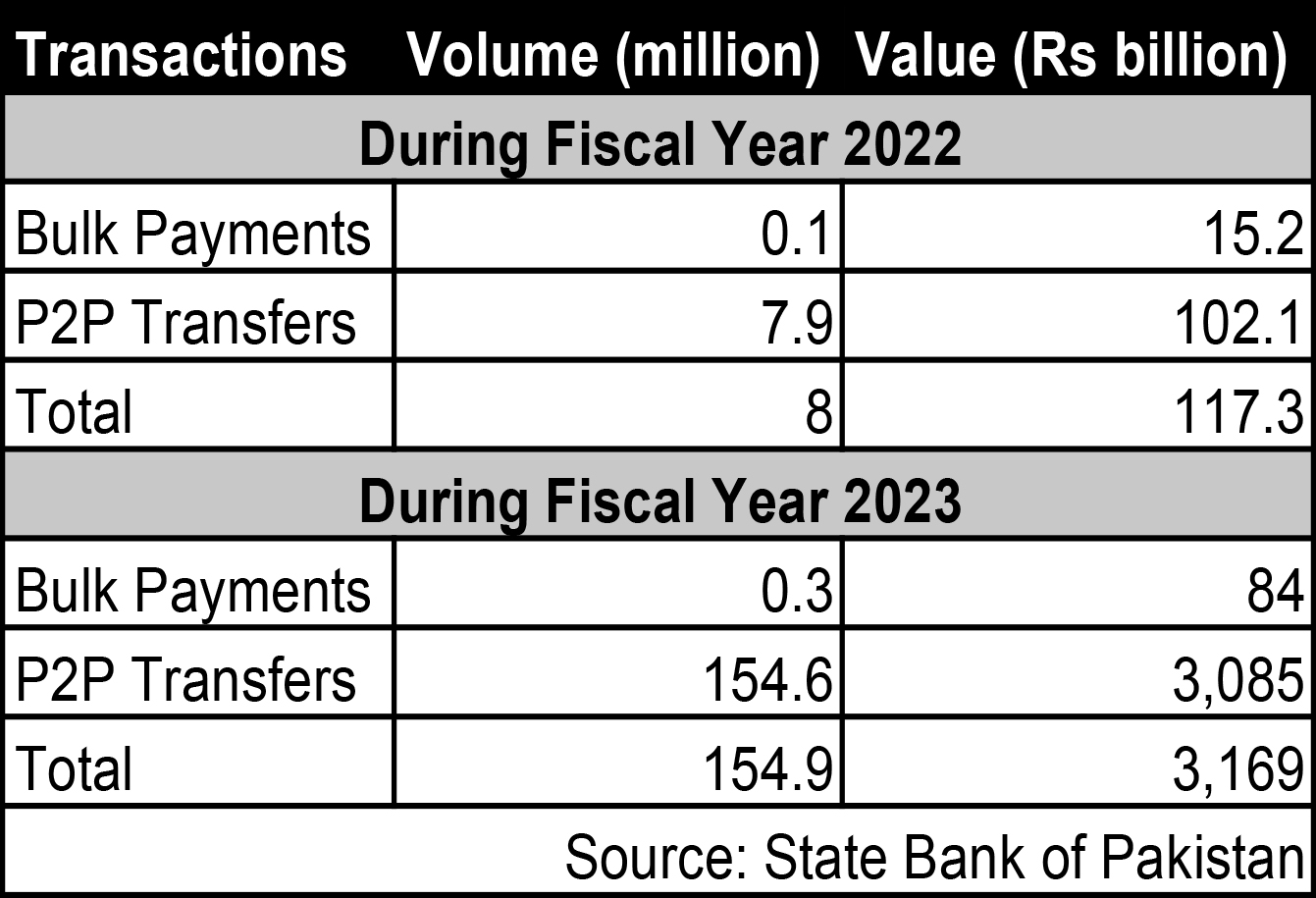

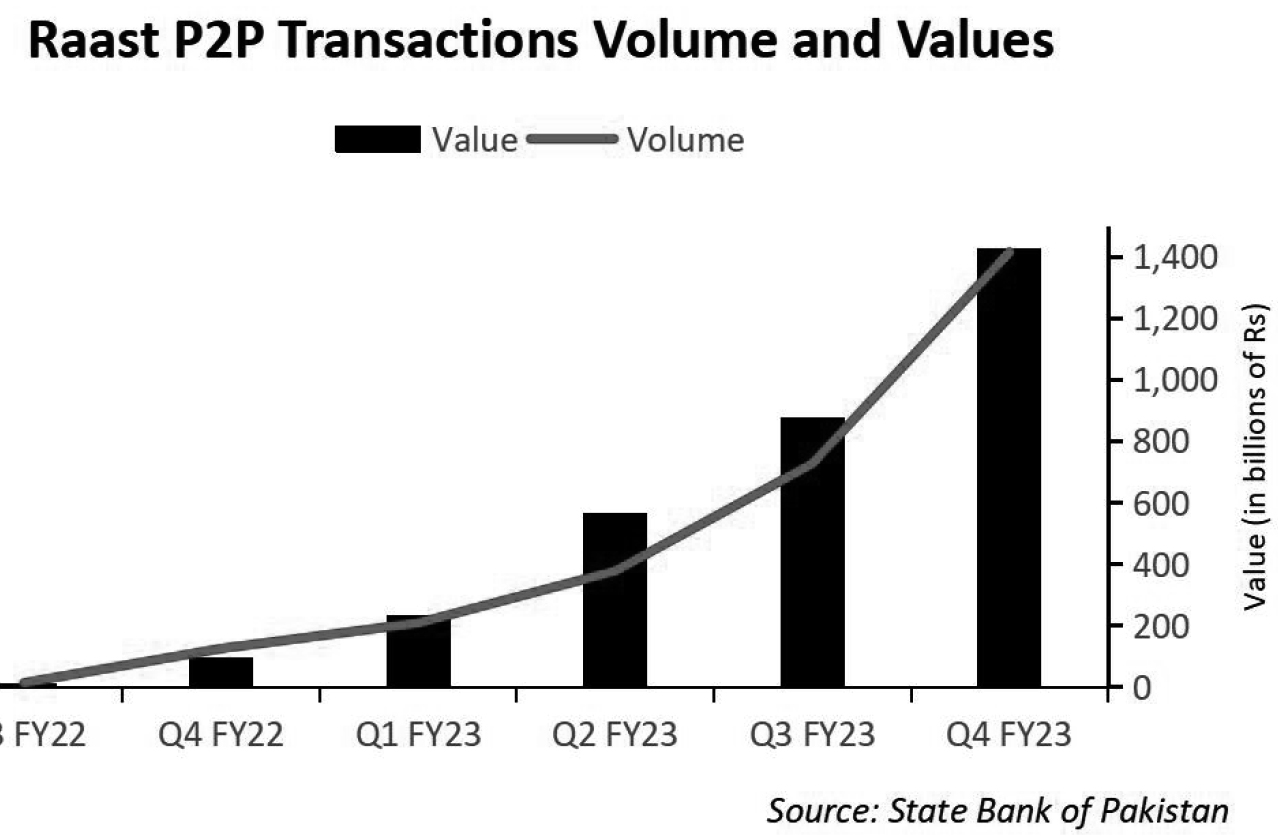

When the SBP first rolled out Raast in 2021 they introduced it with its first feature which is bulk payments. This would allow, for example, companies to disburse salaries instantaneously with the tap of a single button. The idea was to roll out the features one at a time. In February 2022, Raast launched its next big feature, person-to-person payments which would allow simple, seamless transfers of money between two individuals using any Raast power bank account anywhere in the country.

Raast picked up. According to the payment systems review 2023, there have approximately been 20 crore and 80 lakh P2P payments made through Raast worth Rs 4.2 trillion. According to Faisal Mehmood, the head of National Payments Infrastructure at Karandaaz Pakistan, there are approximately 5 – 6 crore unique account holders in the country, and around two thirds of these users now have Raast IDs.

While there have been reports that the increased Raast P2P transactions have been a result of the forced rerouting of IBFT transactions to Raast amid a push from the regulator, the SBP insists that Raast is slowly building its profile. “The progress in terms of numbers that we predicted to reach in around three years, we have already achieved those within a year. If you compare the rate of change, from that perspective, I don’t think that Raast has been a failure,” says Syed Sohail Javaad, the executive director of SBP’s Digital Financial Services Group on Raast’s progress.

Remember, these numbers are only for direct payments made by one person to another. The real test of Raast was always going to be whether or not it managed to become popular as a method to pay businesses. Yes, whether or not you could use Raast to pay for that cold bottle of water on a hot summer day from any kiryana store in the country. And for that to happen, it was always going to be a question of QR codes.

Person-to-Merchant payments – the test case for Raast

So how exactly does Raast propose you pay this kiryana store in exchange for the bottle of water it has sold you? For this Raast was going to introduce P2M payments where a person makes a payment, digitally, to a business entity or shopkeeper (merchant) for goods or services rendered. These transactions involve the transfer of funds from the individual’s account (could be a bank account, mobile wallet etc.) to the merchant’s account.

Now, you might be wondering why we need Raast for this. Card payments at Point of Sale (POS) machines have already become fairly common in the country. The only problem is that we don’t realise just how many small and micro retailers there are in the country. And deploying POS machines to all of them is a painfully expensive process for all banks. On the other hand there is a much cheaper option: QR Codes.

All this requires is that any small kiryana store owner has their own personalised QR code printed out on plastic or laminated and placed at their counter. Anyone with a Raast enabled banking app just has to scan that QR code and make the payment directly with no hassle. Pretty simple, right? As always there is a catch. While the QR code is simple and inexpensive for the average kiryana store, it still requires investment from our banks which will need to size up their digital capabilities and their marketing efforts to bring such a change.

This is perhaps why when P2M was initially supposed to be launched in November 2022, the date was extended to June 2023 and later to September 2023 when the P2M use case finally went live, because the banks were not yet ready for such deployment. Perhaps that is why during his speech at the Pakistan Banking Awards ceremony on November 24, 2023, SBP Governor Jameel Ahmed expressed deep concern, remarking, “This means that most of our banking industry is still lagging behind in Raast adoption, which is deplorable.” Urging immediate action, he appealed to the chief executives of banks not only to fully embrace P2P transactions but also to swiftly incorporate the newly introduced P2M functionality of Raast to expedite the digitisation process for businesses.

So how is the P2M roll-out going

Now that P2M payments on Raast have been initiated, so far, six participants have been onboarded: Bank Alfalah, MCB Bank, Allied Bank, JS Bank, Easypaisa and 1Link. According to the payment systems review of 2023, the SBP is working to bring more banks on board for the P2M journey, with a few currently in the pilot stages.

The SBP has only just initiated the process of deployment. Presently, partner banks are conducting transactions through their employees which means that Raast is not commercially live. Mehmood opined that these banks will start their live transactions by the end of December. He anticipated that by the middle of the following year, at least 15 banks and by the end of next year nearly 27 banks will be onboarded on Raast merchant payments.

Now, overall the Raast P2M scheme has a number of features. You can make requests to pay, there is the option for third-party initiated payments, as well as social disbursements and the instant settlement of PayPak Merchant transactions. These are all important and in some instances pretty cool use cases. But what matters most is the main one — push payments. These are payment transactions initiated by the payer through QR codes. So in the case of our example, you would be the person scanning the QR code for a bottle of water and making a “push” payment.

As a customer, you would scan a merchant’s QR code in plastic at a shop through your wallet or banking application right off your merchant’s phone, and the payment will be processed immediately. The only problem is that QR codes haven’t quite caught on in Pakistan.

There have been serious issues of interoperability in the past. That is because all introductions of QR codes in the past have been done independently by different mobile wallets or banks. This means if JazzCash has put their QR code at a shop, you can’t make a payment through the QR code with anything other than a JazzCash account. What Raast does is enable this interoperability.

Read: QR codes did not bring a payments revolution. That doesn’t mean it’s over

P2M – a catalyst for the death of cash?

The idea is that with interoperability covered, Raast will surge once P2M is well and truly introduced. After all, that is how it happened in India as well with UPI. Conceptually there is nothing wrong with this hope. Rahman, for example, expressed his belief that Raast’s P2M functionality possesses the potential to ignite a digital payment revolution.

“Even if the payments don’t result in staying in the form of deposits for a very long time, as long as they’re touching the banking system in some way or form, ideally digital payments, we’ll start chipping away at cash component of the economy,” Raza Matin founder of Brandverse and Chikoo said. And that’s where he sees Raast evolving payments.

He added that Pakistan is starved for bank deposits. “The only way we’re going to ease access to credit to private individuals, other than the government, is by expanding the bank deposit base. The easiest way to do that is by moving cash payments into the digital realm through Raast.”

But there is something built into the business model here that is different from India and that might just end up having enough of an effect to change the trajectory. MDR is the fee that businesses must pay to banks and payment processors for the privilege of accepting digital payments from customers. It’s essentially a percentage of the transaction amount, and it helps cover the various expenses associated with processing the payment, such as technology costs, fraud prevention, and customer support. So if Bank Alfalah provides its POS machine to a merchant, it will charge the merchant a fixed percentage on each card transaction processed through the POS machine.

In the case of UPI, the Indian government executed a distinctive move in 2019 by keeping the merchant discount rate (MDR) on payments through QR codes at zero. This strategic decision rendered transactions through UPI significantly more appealing.

In the case of Raast, there is no clear instruction on the pricing structure of P2M. Discussing the pricing structure of Raast P2M, Matin highlighted the absence of a defined business model for P2M and the uncertainty surrounding pricing. However, sources in SBP confirmed to Profit, that the regulator has decided to allow the MDR to be a maximum of 1% on P2M, while ensuring that MDR charges are not passed on to customers, preserving free payments for consumers. But this is distinctively different from UPI, which was completely free for both the consumers, as well as the merchants. Why would the SBP not follow the zero MDR model that proved so successful for the UPI?

Why the MDR makes a difference to the banks

This is where two distinct players come in. On the one hand there are the banks. The banks are currently getting an MDR of around 1.5% on card transactions at a much higher investment cost because of the expensive POS machines. If the SBP announces a 1% MDR rate for QR code transactions, which entails much less investment by the banks, common sense dictates that the banks should be willing to bite and promote Raast based QR codes. However, this 1% MDR would somewhat discourage merchants to start accepting QR based payments, instead of the usual cash sales, which they get in full. Not only is there no MDR deduction on cash sales, cash transactions are easier to hide from tax authorities.

It is true, the central bank had initially wanted a model similar to the UPI one with the MDR completely eradicated. This would naturally have worried the banks which are cautious institutions by nature. On top of this, notable banks like Habib Bank, UBL, Bank Alfalah, Meezan Bank etc are in the card acceptance business, earning decent income from MDR. However, a source in the central bank told Profit that it was perfectly doable for banks to charge zero MDR to merchants and not pass because banks also make money from these merchants on other services. The primary source is deposits that merchants have with banks.

On the other hand you have the fintechs which run EMIs and Mobile Wallets. Afterall, SBP could always turn to the fintechs to deploy and promote QR codes, especially if the banks were not playing ball, owing to a zero MDR.

You see, the first adopters of the UPI system in India were not banks either. They were the fintech companies, the giants like GooglePay, PayTM and PhonePe. It is these fintech companies that made UPI a success and are the biggest in terms of apps that use the UPI system. Why were they early adopters? Because they were able to afford such adoption.

Remember that banks are conventional businesses that rely on their own profits to maintain their operations. They are also answerable to the shareholders, public as well as private. So if a big investment does not start giving profits in the short run, banks would be unwilling to make such investments. Mass deployment of QR codes in the market is an expensive endeavour because it requires incentivising merchants by not charging them or lowering the charge enough for them to make it business sense.

On the customer side, such adoption requires incentivising users to use mobiles as the dominant form of payment by giving them discounts. Fintech companies follow a different business model. By virtue of being venture-funded, care a little about losses. In fact, losses mean growth in the startup business which translates into a higher valuation. So incentivising QR adoption on the back of cashback and discounts is pretty much doable for venture capital-backed startups. It is unfortunate for Pakistan that now that the final phase of P2M on Raast is being rolled out, there is a global dearth of venture capital and fintech companies do not have access to abundant venture capital and are required to follow a more ‘sustainable’ approach to business. This is further complicated in Pakistan as some fintech companies are rolling back their EMI operations, which could be attributed to the dearth of aforementioned funding, as well as competition such as from up-and-coming digital banks.

So what does a regulator do in this case? You see the central bank has a vested interest in digitising cash transactions, and charging a fee on digital transactions is always going to be counterproductive. Remember also that Raast is a donor-funded project and an expensive one. If there isn’t enough traction on the Raast platform, donors wouldn’t want to fund it further. And if Raast is monetised, it becomes expensive for merchants who would be unwilling to push digital payments. Unlike bulk payments and P2P payments, the SBP can not ensure a wide adoption of P2M QR codes using force, largely because of the many different stakeholders involved here

So in the case of P2M payments, the approach of SBP seems to be rather cautious. The central bank is poised to let banks make money out of P2M payments by allowing a 1% MDR, and not let it be completely free for merchants. This way SBP will be incentivising the banks to make the QR codes a success. But could the 1% MDR be only in the initial phases. As more and more merchants start deploying QR codes, the central bank might ditch the banks and make it totally free. The central bank has done this before.

Change the game rules, mid-game

When the talk about the digitisation of payments started, there was a growing demand from the banking industry that all stakeholders – the acquirers (the banks that deploy the POS machine), the issuers (the banks that issue the cards) and the merchants – in the process need to be adequately incentivised. All should be able to make money, they said. QR codes had busted because of a lack of interoperability and card payments were a thing of the present. The regulator felt that card payments could be improved further if acquirers were incentivised adequately. POS acquiring requires a hefty investment because the machines are all imported and with the increasing dollar rate, it doesn’t make sense to the banks if they are not able to make money off of merchants. Merchants too, need to be incentivised adequately because a 3% MDR on cards doesn’t make sense for them. Cash makes more sense in this case.

Consequently, in January 2020, the State Bank issued a circular regarding the MDR. The MDR was set between a range of 1.5% to 2.5%, with the share of the issuer capped at 0.5%. The share of the issuers now went to the acquirers and POS acquiring suddenly became a lucrative business and the number of POS machines in the market picked up. Now the State Bank is also a very smart regulator. It perhaps knows that the banks play foul and just want to make as much money as possible, even though they can keep the MDR lower. In a smart move, the State Bank issued a circular in March this year limiting further the issuer share from MDR to 0.2% on debit cards, and removing the lower cap of 1.5% on MDR. What does this achieve? Acquirers have already deployed machines and issuers have already issued cards. None of them can withdraw these back so both issuers and acquirers would now have to settle for less money from these transactions. Instead, by removing the lower cap, the State Bank incentivised further the acquisition of those merchants for whom paying a 1.5% charge on cards was also a problem.

The banking industry cried foul – that the State Bank had in one stroke destroyed their business feasibility by further capping the rate on debit cards and removing the lower cap on MDR, stoking a distrust of the central bank’s policies. What if it is repeated again? What if the State Bank allows a 1% charge on QR codes initially and then makes it completely free only say a year down after the SBP sees an increase in adoption. This distrust also explains why the banks are shirking on P2M payments via QR codes.

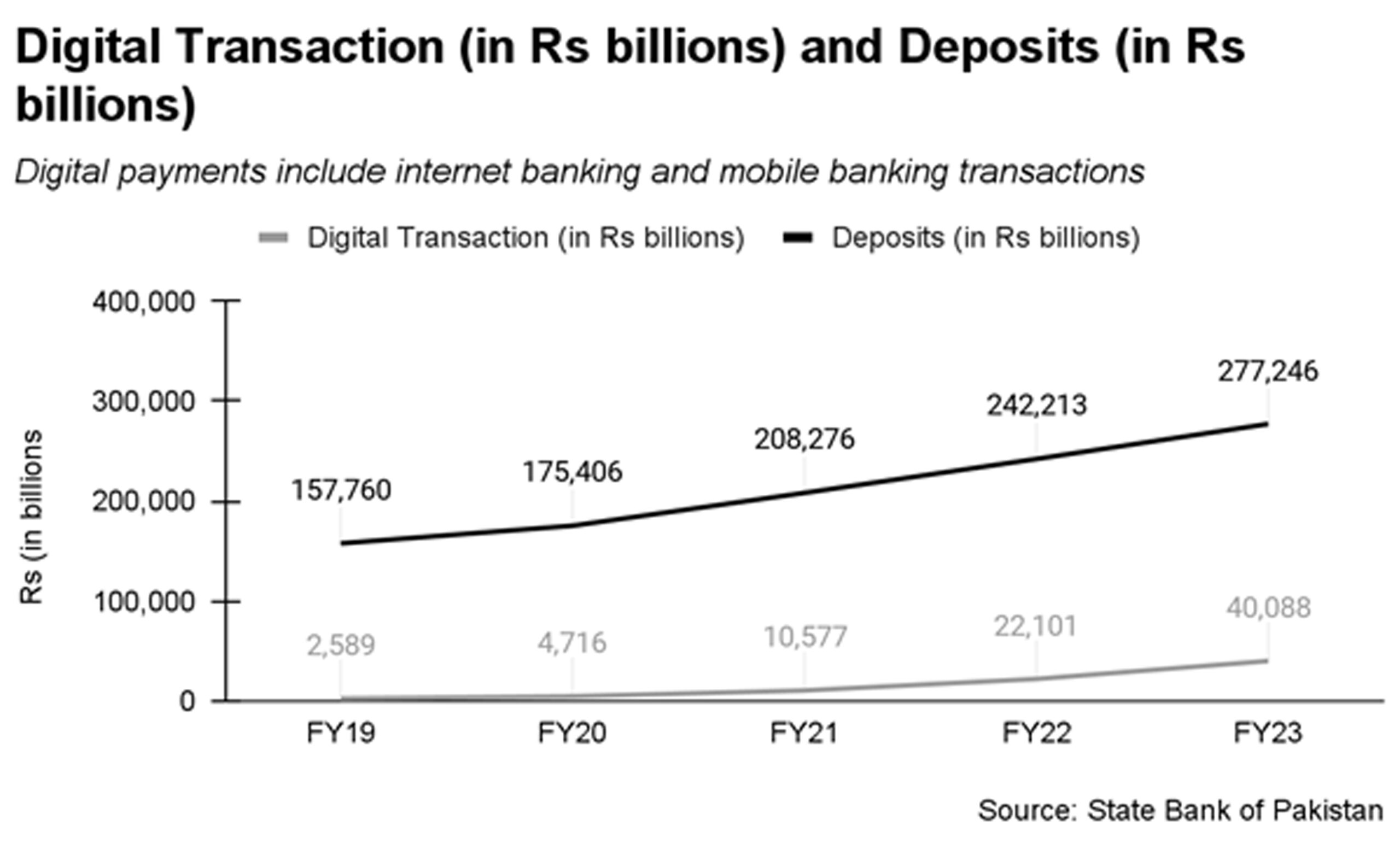

The State Bank is also not wrong in this approach. Commercial banks are failing to look at the bigger picture for short-term gains. If a lower or no MDR incentivises digital payments, cash turns into deposits which translates into better earnings for the banks. Numbers also align in this regard. According to the data from the State Bank, the surge in digital transactions is paralleled by a notable rise in deposits within the financial landscape. Remarkably, the correlation between the upsurge in digital transactions and the escalation in deposits over the last five fiscal years stands at an impressive 97%, underscoring a robust positive relationship between these two variables.

Sources at the State Bank also said that in the absence of VC funding for fintech companies and to allay the concerns of the banks with regard to costs associated with acquiring merchants and getting customers used to making P2M payments, the State Bank was contemplating setting up a fund with the help of the government to subsidise such transactions. This would be a good move until the time the VC funding picks up, which is likely to start happening next year, which would bring the hungry young guns in the fintech scene back in the game.

Matin comments on the predicament faced by banks. As mentioned earlier, some “Banks find themselves in a slightly awkward position because they already have products that cater to this use case and make boatloads of money with cards. Having invested heavily in card issuance and promotional efforts, banks now grapple with the task of balancing these services and seamlessly integrating Raast P2M into their suite of offerings for both merchants and consumers,” commented Matin.

On the other hand, Mehmood raised the point that while cash payments are inherently more costly, banks don’t charge anything on cash transactions, unlike MDR applied to digital payments. According to SBP’s unconsolidated financial statement for fiscal year 2023, banknote printing charges amounted to Rs 21 billion.

“Digital payments have a one-time cost. If a transaction occurs 500 times, it won’t get damaged like a physical note. However, in digital payments, we often ask shopkeepers who work on very thin profit margins for an MDR of 1.5%. The shopkeeper, a small kiryana store owner, for instance, has a margin of Rs 3-4. MDR of 1.5% would erode his profit margin. Then he also has to cover expenses like rent, electricity bills, worker salaries, and support their own family, so you’re essentially taking a percentage of their income away.” Mehmood argued that this practice is unfair and calls for addressing these issues.

He also highlighted international practices, stating that in Europe, the MDR on credit cards is 0.4%, and on debit cards, it’s 0.2%. In contrast, in Pakistan, the MDR starts at 1.8%, regardless of whether it’s a credit or debit card. Mehmood emphasized the significant difference between 0.2% and 1.8% and urged the industry to address these issues. He argued that simply imposing MDR and commissions on all transactions is not a viable solution. To make a successful cashless ecosystem, he suggested the need for an alternative plan, as the current approach, especially in Pakistan, is unlikely to work.

Learning from the mighty UPI

Raast being a success is contingent upon addressing the aforementioned issues. If done rightly, it could mirror the success of UPI in India. According to the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), over 11 billion transactions worth INR 17.16 trillion (equivalent to Rs 59.21 trillion) via UPI took place in October 2023. Currently, there are 300 million UPI users and 500 million merchants who use UPI to accept payments for their businesses.

By the end of 2022, UPI transactions had reached a staggering INR 125.95 trillion (equivalent to Rs 429.6 trillion), accounting for almost 86% of India’s GDP for the financial year.

The growth of UPI is remarkable, with transactions surging by over 90% between 2021 and 2022, despite a high base. The platform continues to attract more customers every day and is expected to reach INR 825.73 trillion (equivalent to Rs 2,816 trillion) by 2026.

In the case of India, UPI got traction when it launched P2M and by 2025, it is estimated that 75% of the payments processed on UPI would be P2M payments.

What did the Indian government do differently to reach such numbers? First, it abolished the very same MDR that, as discussed above, is holding Raast back.

While this move made digital payments appealing to merchants, it adversely affected the bottom lines of banks as banks lost one of their revenue streams. Besides, the cost of investing in technology was too high for the banks and the lack of business value associated with technology, at the time of its release left banks with no incentive to scale up the new technology.

Consequently, banks resorted to ceding the UPI space to non-banks like fintech and third-party aggregator platforms like PhonePe, Google Pay, and Paytm which ultimately became a household name in India. These non-banks were venture-backed. Together these three TPAPs now account for nearly 96% of UPI transactions.

Drawing parallels between India’s UPI and Pakistan’s Raast

Profit spoke to the Raast team who requested to remain unnamed. The Raast team said India’s UPI had additional extraneous advantages, such as the government’s demonetisation initiative. The team further added that if demonetisation hadn’t happened and platforms like Google Pay were not present in India, UPI wouldn’t have been able to attain the same level of scalability it ultimately achieved.

Indeed, UPI was launched at a time when there was free money circulating in the economy and startups were raising big rounds of money. Raast is late in the sense that now funding for startups has dwindled and interest rates are soaring high. Thus, fintechs and non-banks in Pakistan no longer have the cash to burn.

When asked if the fintech or startups in Pakistan would be willing to step up, Matin asserted, “It is not a question about whether startups will want to integrate with Raast or whether they can afford to integrate it, it’s whether they’d be allowed to intervene.”

“If you’re expecting the startup and developer community to help you drive adoption and usage of Raast, you need to make it easier for them by publishing technical specifications for your platform, having a developer portal, and not wrapping up access in bureaucracy,” said Matin. He opined that Raast should be one of those pieces of common digital public infrastructure that’s open to all entities, as long as they can meet a defined standard for legitimacy.

On the other hand, Mehmood told Profit that fintechs have not been coming forward. “Lack of funding could be one reason. But more than that I think there is a gap in understanding.” For instance, he said multiple fintech CEOs were still unsure of the difference between P2P and P2M payments, and what was so special about merchant payments.

“The industry is still confused and tied to the term digital payments and cannot differentiate digital payments from instant payments. Our industry is still trying to figure out how to implement these use cases. This is why enabling their systems onto Raast merchant payments is relatively low. Once they understand only then they will go to merchants or make changes to their systems”.

More importantly, the zero MDR also made transacting through UPI more attractive.

“In India, NPCI announced zero MDR on transactions up to INR 3000, and even when they introduced MDR later, it was very nominal. This is why 75% of merchant transactions in India are now happening digitally via UPI,” said Mehmood.

Mehmood added that apart from zero MDR, support from the government also played a major role. In fact, the political ownership of UPI was one of the major reasons for its success. Modi ji took UPI very seriously under his Digital India ambition and turned UPI into a product that his government was able to later export to other countries. Such ownership was visible under Imran Khan who launched the Raast platform when he was in government and was passionate about Digital Pakistan.

“The Indian government set specific targets and allocated significant resources. The Indian government has spent $1.6 billion annually for the adoption of digital payments, including advertising. They have created 2.5 lakh digital payment support systems across India to address any digital transaction errors that shopkeepers might encounter. India has made substantial investments in promoting digital payments, and that’s why digitization has been successful there,” informed Mehmood.

Pakistan may not have the financial resources to match India’s $1.6 billion investment, but it can still take meaningful steps to promote digital payments and drive digitization in the country. It might need to explore creative and cost-effective strategies to achieve this goal.

Mehmood believes that it is time for the government to step up and drive digital payment acceptance. “Most of the merchant payments are cash-based. And hardly anyone pays taxes. So, I think it is about time that the government announces a policy saying that there is an amnesty for 5 years on any transaction under Rs 5000 that happens digitally.”

He added: “If it continues, in five years, people will become habitual of digital payments. By that time, you will have built enough data for taxation. And even if you levy a nominal 0.1% tax then, you could reap enough revenues.”

According to Mehmood, an average person does two financial transactions in a day. Around 250 million people would translate into 500 million transactions. But the size of digital transactions is only around 3 million per day which means that less than 1% of payments are digital in Pakistan. Whereas in India, 75% of merchant payments are digital.

The future of Raast

As we contemplate the potential trajectory of Raast in Pakistan, the question looms large: Can Raast become Pakistan’s UPI? Matin rightly emphasises that Raast is a force to be reckoned with, capable of disrupting payment businesses profoundly. Drawing parallels with India’s UPI, Matin pointed out that Raast is something that you don’t want to sleep on because Raast can disrupt payment businesses like nothing else.“UPI in five years has upended the Visa and Mastercard in India,” said Matin.

The success of UPI in India was underpinned by crucial factors—zero cost on merchant payments and substantial government support, with significant investments to ensure widespread acceptance. The pivotal question now revolves around whether the SBP can replicate this success with P2M adoption in Pakistan. The answer hinges on the SBP’s policy initiatives to drive P2M adoption and, perhaps more critically, on the willingness of banks and fintechs to embrace and champion this transformative shift.

Raast stands at a crossroads, and its performance in the upcoming P2M phase will be pivotal. The challenges faced, such as pricing structures and merchant onboarding, need to be navigated effectively. The SBP’s ability to craft and implement policies that incentivise digital transactions, coupled with industry collaboration, will shape Raast’s destiny.

Raast was supposed to have an open API but it doesn’t. How can developers use it without an API? It’s just IBFT by another name now.

The other problem with Raast is that your mobile phone number becomes your account number and there’s no way to change that. If you have the same mobile phone number registered on more than one bank account that means you can only register to receive Raast payments on one account.

so government can keep an eye on my money and transactions? Government will get to know my money and my spending completely?

Without an API for eCommerce developers in Pakistan, it’ll be not helpful. However as it is a starting point so in future we’ll have an API for eCommerce websites. It can help online sellers to get easy Payment Gateway for fast local payments.

LOL you must be a unicrom company owner?