Avid followers of this publication will have observed our unwavering stance on critiquing the transformation of Pakistan’s banking sector into leverage hedge funds facilitated by the Government of Pakistan.

While we maintain our analysis of the strategies implemented by prominent banks and financial institutions, it is important to acknowledge another aspect often overlooked in this narrative. The evolving situation is partially influenced by the government’s monetary and fiscal stance, which, in turn, is impacted by the prevailing macroeconomic crisis and the necessity to align with the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) conditionalities.

Part of our critique revolves around the crowding out of private sector credit. This issue, currently, is primarily attributed to the elevated policy rate. Pakistan’s central bank cumulatively raised the policy rate by 15% between September 2021 to June 2023. Almost a year later, the rate still stands at an all-time high. The SBP’s tight monetary approach is, to some extent, influenced by the conditions imposed by the IMF.

“With inflation still well above target, monetary policy should remain appropriately tight and vigilant against emerging pressures. The recent deceleration of inflation is welcome and will reduce the high burden on Pakistani society, and particularly the most vulnerable. Monetary policy should remain data-driven and attentive of stickiness in core inflation, as well as resolutely address any emerging risk. Guiding inflation back to target is imperative not only to buttress a sustainable recovery but also to build central bank credibility,” read the staff report released last week.

High interest rates have implications for the private sector businesses of Pakistan. In a previous conversation with Profit, Mustafa Pasha, chief investment officer at Lakson Investment Limited bemoaned the waning enthusiasm of banks to extend credit to private enterprises. “Private-sector borrowing costs have gone up due to high interest rates. Financing availability from banks has been reduced because banks are less willing to lend to the private sector and prefer lending to the government. Demand and supply for financing have gone down, squeezing private-sector credit. This also means that greenfield projects and new investments have decreased while working capital requirements have increased.”

A bank’s business is to accept deposits from customers and lend funds to other customers. But with inflation hitting record highs and interest rates still capped at 22%, businesses haven’t exactly been lining up for credit. So what do the banks do? They lend to the one entity that does constantly need money no matter what: the government.

Moreover, the incentive for lending to the private sector was revoked in February. In late February 2023, the government exempted the tax amendment for the year 2023 imposed on income derived from investments in government securities that was applied to the sector in 2022. This tax amendment introduced steep tax rates of 55%, 49%, and 39% for banks’ investment income based on their gross advance (lending) to deposit ratio (ADR) falling within the ranges of up to 40%, 40-50%, or over 50%, respectively. Without the ADR-based tax in effect, banks could freely invest in government securities.

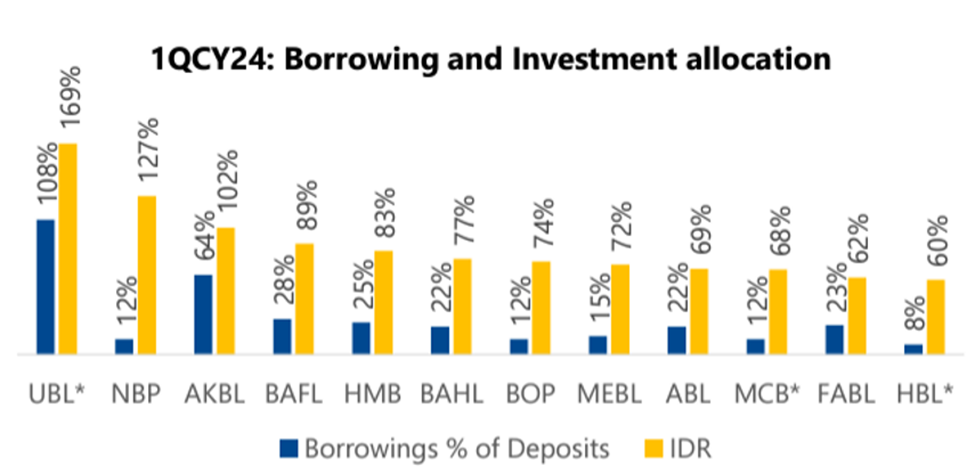

Lending to the government is profitable at a time like this. The inherent risks associated with engaging in lending operations, particularly in the current high-risk environment, have also constrained the growth of the banking sector’s credit portfolio. This is reflected in a low Advances-to-Deposit Ratio (ADR) of only 44% as of the end of 2023. This means Pakistan’s banks lent Rs 0.44 for every rupee they received from their depositors in 2023, reflecting a poor state of affairs in private credit. Whereas investment to deposit ratio stood at 91%.

At the end of March 2024, ADR trimmed down to 42% while IDR inched up to 93%. This means that the majority of the deposits with the banking sector are being lent to the government, resulting in crowding out of the private-sector.

The government’s never-ending appetite for deficit financing means that the local financial institutions have ample liquidity in the form of benevolent lending by the SBP aka repo transactions.

Consequently, the banking sector reported record-high core income and profitability despite high inflation and a 50% tax rate. Commercial banks posted an impressive 83% earnings growth during 2023, with almost all banks recording historic profits. At the same time, some financial institutions increased the size of their balance sheet by multiple times, while other businesses struggled.

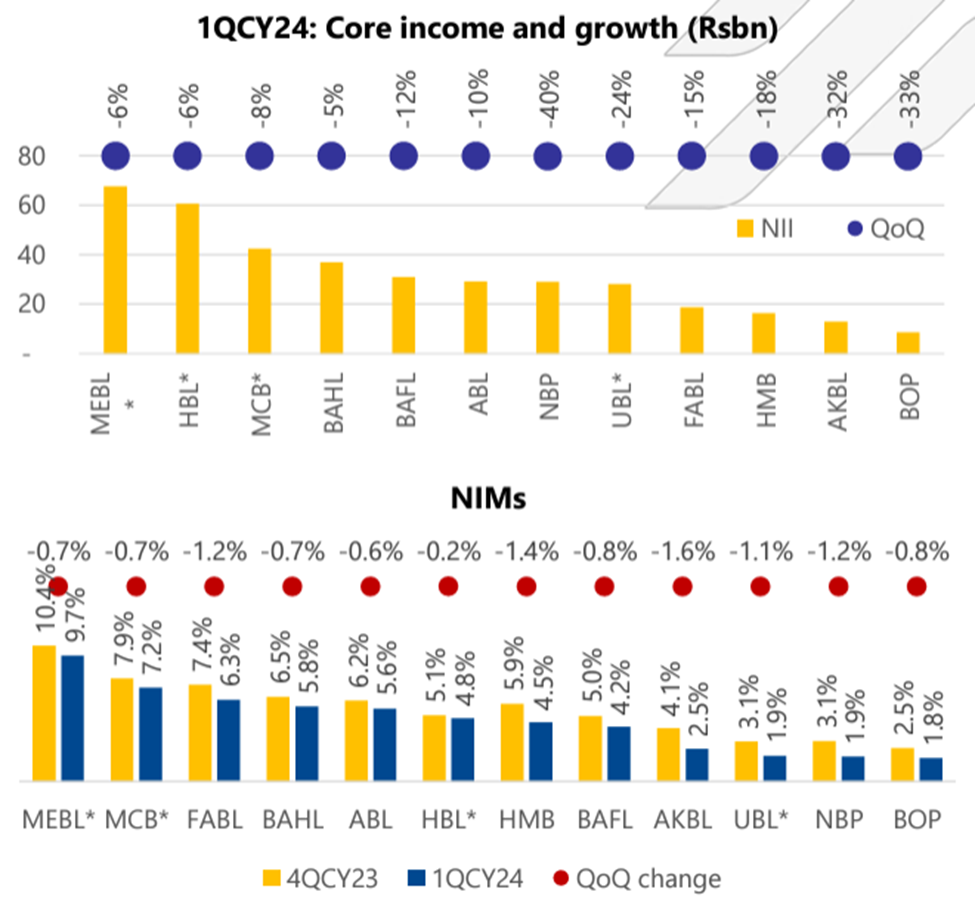

However, the trend is shifting. Following a sustained period of increasing income, the core earnings of Pakistan’s banking sector took a downturn in the first quarter of 2024, marking an end to a 12-quarter streak of uninterrupted growth, as indicated by a research report from JS Global. This is the first time since the first quarter of 2021 that net interest income (NII) has fallen on a quarter-over-quarter (QoQ) basis. This comprehensive assessment focused on a sample size of 12 banks, which collectively represent a whopping 85% share of the entire banking sector market.

This decline was driven by a decrease in asset yields, while funding costs remained flat. What does that mean?

Declining asset yields

Banks earn interest income by lending out funds to borrowers, such as individuals, businesses, and government. Banks usually acquire funds for lending and investing from deposits and borrowings.

Repurchase agreements or repos account for most of the banking sector’s borrowing. Repos, or injections, are a tool used by the SBP to manage liquidity in the interbank money market. In repos, the SBP (injects) lends money to commercial banks against eligible collateral. The banks then use this money to buy government securities like Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIB) and Market Treasury Bills (MTB).

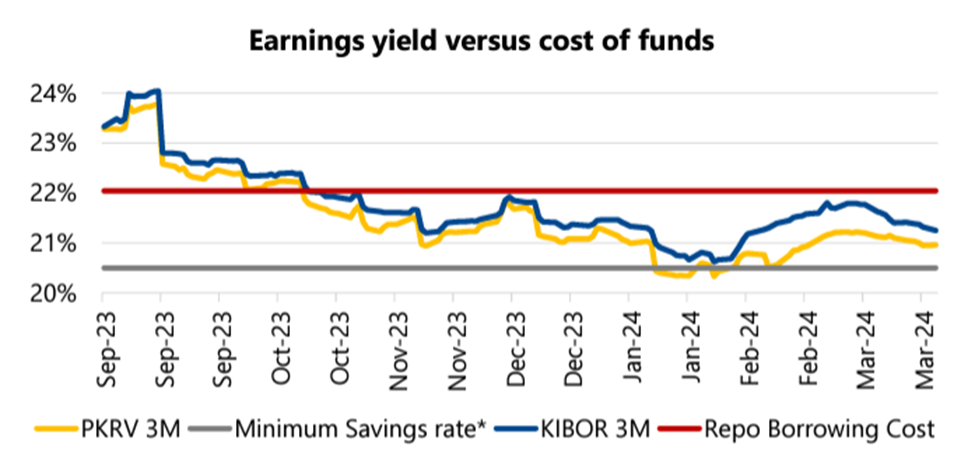

However, recently the predicament facing banks is that the borrowings used to invest in government securities are now proving to be a costly endeavour. The cost of borrowing and the interest paid on deposits held with banks are linked to the policy rate. On the other hand, returns on banking assets; investments and advances, are influenced by secondary market sentiments, as demonstrated by the Karachi Interbank Offered Rate (KIBOR) and the secondary market yields on T-bills and PIBs.

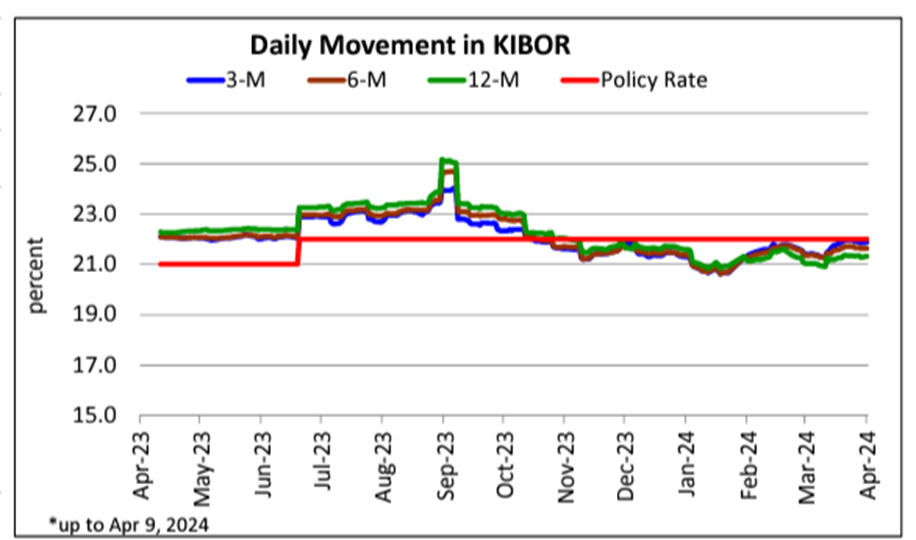

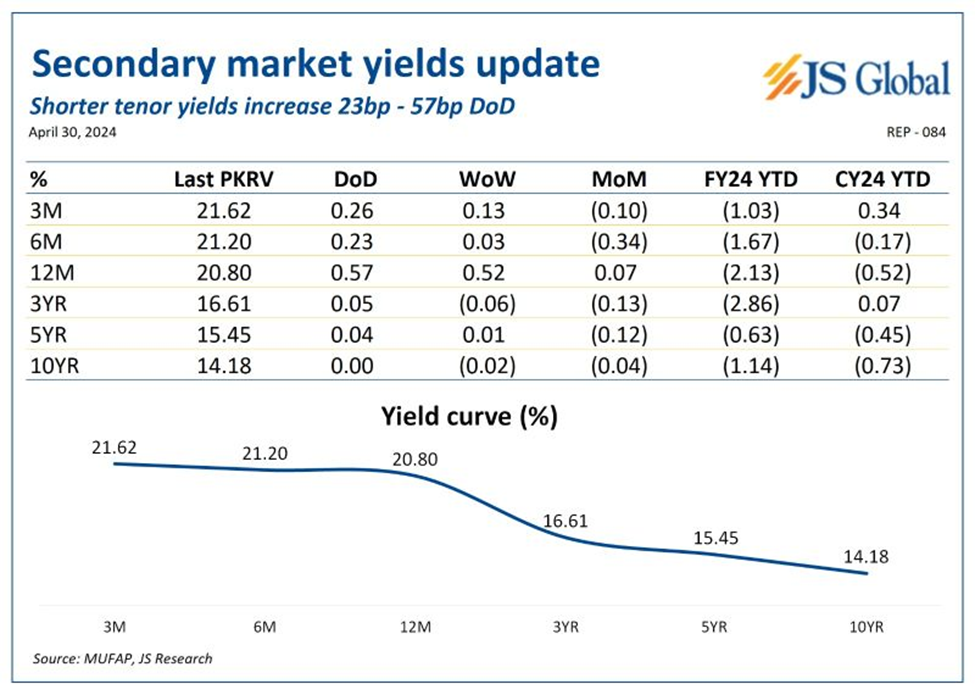

Although government treasuries are also significantly impacted by the policy rate, they are also influenced by sentiments in the secondary market. Yields in the secondary market have been below the policy rate since November 2023 as market anticipation of rate cut increased as macroeconomic indicators improved.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan

While yields for shorter-tenor securities have inched up. However, the market has factored in rate cut for longer tenured instruments.

As the savings deposit rates and the borrowing rates are pegged to the policy rate, the banking sector’s cost of funds has remained unchanged. This has resulted in the contraction of core income in the first quarter of 2024. The contraction will continue if the expectation of rate cuts persists while the SBP continues to hold on to the current policy rate. This scenario could significantly diminish the sector’s margins and potentially turn them negative, especially for certain tenured securities.

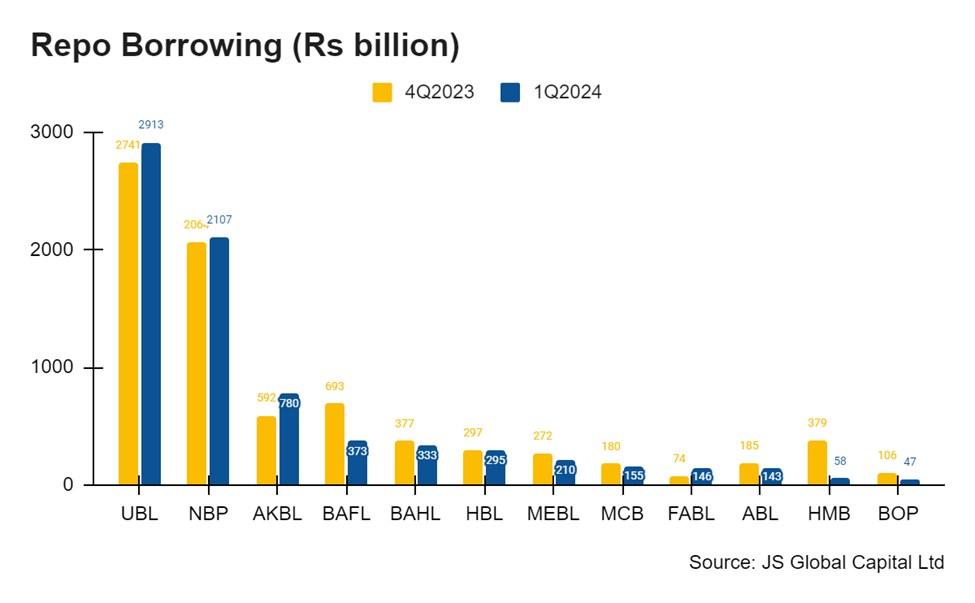

To minimise losses, some banks have reduced their exposure to repos. These include Bank Alfalah, Habib Metropolitan and Bank of Punjab. Yet there are still some banks like United Bank Limited (UBL) and Askari Bank (AKBL) that have further expanded their repo borrowings. As per the JS Global report, repo borrowings are now skewed to 3 banks – UBL, National Bank of Pakistan and AKBL, as these 3 banks account for ~57% of the outstanding repo borrowings.

To minimise losses, some banks have reduced their exposure to repos. These include Bank Alfalah, Habib Metropolitan and Bank of Punjab. Yet there are still some banks like United Bank Limited (UBL) and Askari Bank (AKBL) that have further expanded their repo borrowings. As per the JS Global report, repo borrowings are now skewed to 3 banks – UBL, National Bank of Pakistan and AKBL, as these 3 banks account for ~57% of the outstanding repo borrowings.

IFRS-9

The banking sector’s declining yields coincided with the implementation of IFRS-9 by Pakistani banks, potentially resulting in the recognition of accelerated provision losses by these institutions. However, most banking institutions maintained sufficient capital buffers due to record profitability and liquidity over the past year.

“With implementation of IFRS 9 from 1 January, 2024, non-performing loans stock witnessed one-time adjustments, resulting in higher accretion during the quarter. Accordingly, credit loss allowance was also reported, maintaining 100%+ Coverage ratio by most players”, read JS Global report.

Deposits

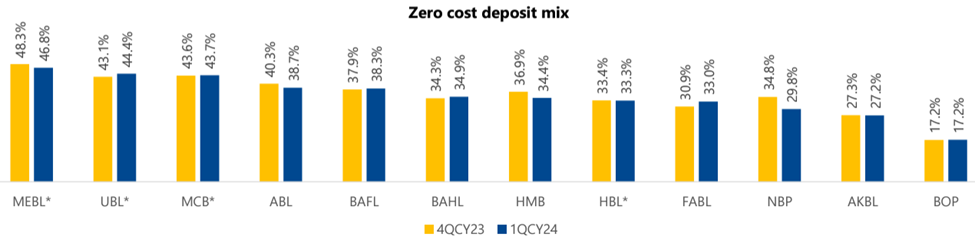

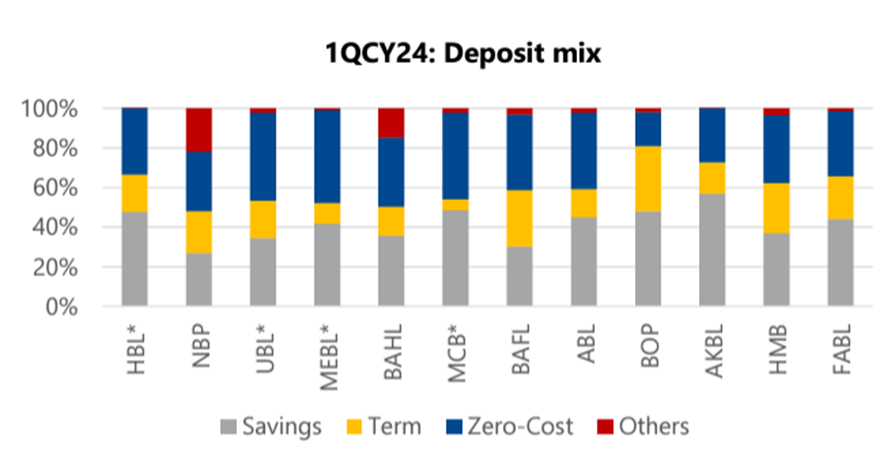

While deposits are increasing, zero-cost deposits are declining. Zero-cost deposits for most banks declined quarterly, which shows that the consumers are moving to interest-bearing accounts in the high-inflation environment.

This is not good news for the banking sector which is already suffering from squeezing margins. In the ongoing high-interest rate environment, zero-cost deposits hold significant value for banks. These deposits serve as the holy grail for banks as they can utilise them for lending purposes or invest them in government securities. Both of these options generate interest income for the banks, contributing to increase in profitability and overall financial performance which explains the astounding increase in income.

The fiscal impact

The fiscal impact

While the normalization of banking profits seems inevitable once the macros stabilize, one crucial aspect that should not be overlooked is that the fiscal repercussions of the sovereign-bank relationship are often exaggerated. Although more than half of federal revenues are consumed by debt servicing, with 90% related to domestic debt, a substantial portion of these funds circle back to the government through dividends from the SBP. According to the latest fiscal accounts, in the first nine months of fiscal year 2024, the SBP dividend amounted to approximately Rs. 972 billion. Additionally, the sovereign is on track to achieve a primary surplus for the first time since 2004.