At the beginning of June, Sher Afzal Marwat was given the floor in the lower house of parliament. The address he made was unusual from the many other speeches he has given in parliament. With his leader imprisoned,and his party in shambles, Mr Marwat was speaking on this occasion not as a PTI parliamentarian but as a constituency politician.

The normally fiery lawyer turned politician spoke with relative calmness as he made a case for the people of Lakki Marwat. Outside the parliament house, a small group of people from the KP District were sitting in protest. The subject of their ire, and of Mr Marwat’s speech, was the Lucky Conglomerate.

Since 1993, the Lucky Group has been operating a massive factory in Darra Pezu in Lakki Marwat, which is one of the largest cement manufacturing facilities in the entire country. Sher Afzal Marwat’s contention was that in the past two decades, Lucky Cement had failed to give back to the district in any tangible way.

It was an interesting debate on the floor of the national assembly raising an important question: Do companies have a legal responsibility in addition to a moral one to look after their local communities? Mr Marwat and the people of his constituency, NA47 Lakki Marwat in KP, were of the opinion that there should be. But it turns out Pakistan doesn’t really have any legislation that compels companies to spend in the way of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), let alone where they should be spending any CSR budget they might have.

The question is whether such laws should exist.

Sher Afzal Marwat goes to bat for the people of Lakki Marwat

In his speech to the National Assembly, Mr Marwat claimed that despite having its factory in his district since 1993, Lucky Cement hasn’t invested a single penny in the area under the head of CSR, royalty or what he calls as “surface rent” to the local community, despite earning billions of rupees in profit from the business.

He claimed that the cement company, which employs over 5000 people across the country provides a job to only 44 people of Lucky Marwat, and that too of lower grade. The company, according to him, has established a welfare hospital, but in Karachi and has not done anything of the sort in the vicinity of their factory in Lucky Marwat. Even when due to unchecked manufacturing, supply and transportation activities of the company, the infrastructure and environment of the area have been badly damaged. Pollutants putting public health at risk and industrial activity destroying the native ecosystem. Chemical dust created by the factory is also causing health issues to the lives of people living in the area.

He also claims that roads are damaged after every one or two years due to heavy trucks roaming around the factory and area.

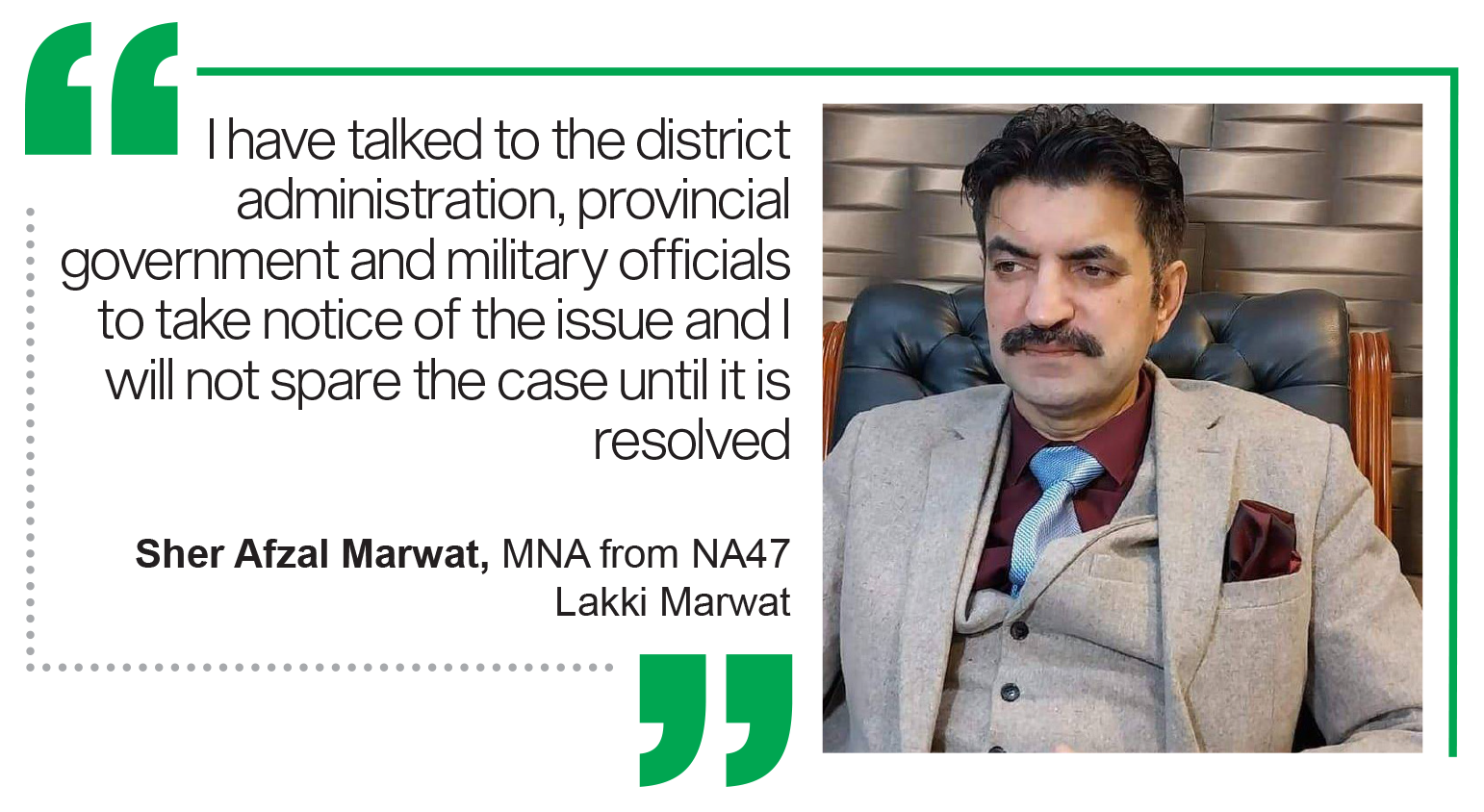

The company, according to him, has paid billions of rupees as dividend to its shareholders but it has not made a contribution to the wellbeing of people of Lucky Marwat. “I have talked to the district administration, provincial government and military officials to take notice of the issue and I will not spare the case until it is resolved”, said Marwat while addressing a protest in the area.

He claims at least a five percent dividend of the company needs to be given to the area under CSR. District administration confirmed that not a single rupee has been given by the company since its establishment in 1993 to date under the three heads.

But wait, how can a lawmaker hold a company to give its rightfully earned and taxed profit to the people? Does Lucky Cement legally owe anything to the people of Lucky Marwat? And does it amount to Rs 65 crores (5% of its FY23 profit)?

Does Marwat have a case?

In one word, the answer is, no.

When approached sources in the ministry of industries, SECP and industry, Profit found out that neither the company rules set by SECP nor the licence being issued by the industries ministry bind a manufacturing company to spare a specific share of its CSR fund to the locals and community living in the surroundings of the factory.

As such, Mr Marwat’s speech was also a bit of a surprise for the management at Lucky Cement. Speaking to Profit, Lucky Cement’s CEO, Muhammad Ali Tabba, confirmed what the SECP and ministry of industries had also said: there is nothing that binds a company to use a specific share of its CSR to the local community where it is based. Mr Tabba went on to say that despite this the company is already carrying out a number of CSR activities in the area.

“Lucky Cement affirms commitment to national development amidst criticisms. The company has played a vital role in Pakistan’s economic growth, contributing approximately Rs 285 billion to the national exchequer since its establishment. Notably, over 70% of its workforce hails from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and our neighbouring areas, emphasising the company’s commitment to local employment and community involvement near its manufacturing facilities,” he said in a written response.

“Moreover, Lucky Cement has invested significantly in social welfare initiatives, with around Rs 78.6 million dedicated to education programs annually and Rs 8.15 crores annually to healthcare efforts, benefiting underprivileged communities. Additionally, the company has allocated approximately Rs 21.4 crores to support infrastructure projects and provide assistance during disasters, showcasing its dedication to both economic development and social responsibility.”

Of course, this written response does not really address the question. Why has Lucky Cement not invested in their local community? It is true enough that they are not under any legal obligation to do so, but if they do have a CSR budget does it not make sense to spend it in Lakki Marwat?

The problem is one cannot fault Lucky Cement for this. It can be argued that the company should have been more aware of this, but the responsibility falls on local administrations.

To cut a long story short, does the company legally owe anything to these areas while it uses their resources? Not in Pakistan. Is there a logic and precedent for it? Absolutely.

Most of the developed world employs community based agreements (CBAs) before they allow any industrial activity in their constituency. It is a legally binding contract between a company and a community that outlines the benefits the company will provide to the community in exchange for the community’s support or acceptance of a project.

It can range from assurances on job creation and infrastructural improvements to environmental protections and sometimes elaborate community programs.

While most CBAs are done by the virtue of the far sightedness of a city’s administration or government. There are even examples of jurisdictions in the world that mandate a Community Based CSR or CBA, before any industrial activity is started. This includes specific jurisdictions or states in countries like the United States, Canada or Australia, and other developed countries.

When it comes to legislation around CSRs, Pakistan is far behind other countries. The country does not mandate any form of CSR for the companies. Meanwhile countries like India and Brazil have specific laws in place whereby a company is required to spend a certain percentage of their profit in CSR, which is what Sher Afzal Marwat wants from Lucky Cement as reparation.

Even though there is no such law in place, examples of community welfare by companies are more than plenty, even in Pakistan. And for a company like Lucky such CBA agreements would be greatly beneficial. Not only do they have one factory in Lakki Marwat, their other production facility is in a similarly low-development area in Sindh’s Jamshoro District.

The environment factor

While analysing the existing rules, it was also revealed that the environmental protection agency (EPA) under the Ministry of Climate Change was the only government body, which has some rules to force any company to make investment into the environment and wellbeing of locals.

However, the EPA rules largely bind the firms to ensure the reducing risk of environmental hazards through different means and procedures set in the rules and guidelines.

Director General EPA Farzana Altaf Shah, when contacted said that the EIA/IEE regulations are set for conducting environmental impact assessment for any project and related issues.

“We, through the EPA rules, give specific guidelines of inspection related to socio economic issues while asking the companies to invest in environmental protection, water supply, school, hospital and other possible facilities to the locals being the immediate affectees of any intervention in the environment,” she added.

Interestingly, in guidelines given by EPA Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to Lucky Cement for extension of its factory in Lucky Marwat, the agency, while sharing other rules and guidelines, has clearly mentioned the mandatory facilities to be provided to the local community.

“A proper CSR document keeping in view the quantum of the project activity and demands of the locals shall be finalised specifically for the proposed line having year to year project wise activities detail. The activities may include but are not limited to provision of new water supply schemes, school construction, scholarship, dispensary etc for locals,” the guidelines read.

“Furthermore, two committees for social and environmental issues shall be constituted in consultation with locals with intimation to the agency,” it adds.

According to the guidelines the share of the locals in managerial /skilled jobs shall be increased and proper plan/documents shall be submitted in this regard to the agency. Moreover, employment shall be provided to the local people of the nearest union councils in technical/non-technical jobs. Details of the same shall be provided to EPA.

The Profit/Dividend equation

And then there is the flip side. It is clear that Pakistan does not have any laws for CSR management, and as such Lucky Cement is under no obligation to spend on the people of Lakki Marwat as part of its CSR activities.

One can of course argue that there should be, and plenty of precedent exists in the world for this. The only problem is that of shareholders. For a publicly listed company like Lucky Cement, one might argue that it is the right of the shareholder to decide whether they want to invest any of their earnings that they get through dividends into some kind of charitable or CSR activity, and what this activity should be.

That, of course, is an ideal world. In reality, corporations take on lives of their own and become entities that have decision making power. As a part of that, it would not be so strange if the government legislated on CSR laws or at least negotiated with companies on the behalf of small districts where these companies operate.

The numbers:

According to an earlier Profit report published in September 2023, Lucky Cement has resolved to conclude a three-year intermission in its dividend disbursements to shareholders by dispensing a Rs 18 per share dividend to end its fiscal year (FY). At Rs 18 per share, this is the most substantial dividend payment per share the company has made since FY 2018 — when the company made a payment of Rs 13 per share.

However, cement companies are renowned for not paying large dividends to begin with. The matter is further bewildering when viewed in conjunction with Lucky’s share buyback activity over the past few months.

The company claimed Lucky Cement’s flagship business is cement, but now only 20% of its profits emanate from local cement operations. The remaining 80% are derived from the company’s of autos, power, chemicals, and international operations.

As per a report Lucky Cement’s profit-after-tax amounted to Rs 38.32 billion, a massive increase of over 109%, during the half year that ended December 31, 2023, compared with Rs18.32 billion in the corresponding period of the previous year on account of higher sales and lower cost of sales.

On a consolidated basis, the company’s Earnings per Share (EPS) jumped to Rs117.19 against Rs49.23 in the same period of the previous year. Lucky Cement’s net revenue increased by nearly 12% to Rs206.52 billion as compared to Rs185.21 billion recorded in the previous year.

However, the cost of sales declined to Rs143.46 billion in 1HFY24, as compared to Rs146.14 billion recorded in the previous year.

Resultantly, the gross profit of Lucky stood at Rs63.06 billion, as compared to Rs39.06 billion, an increase of over 61%.