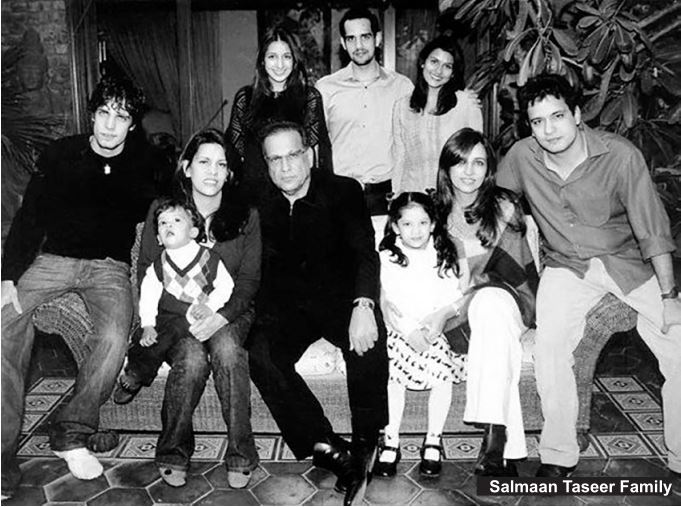

It was shortly after sunset in Islamabad on January 4, 2011. Almost every liberal in Pakistan remembers exactly where they were that day, and that moment, when all illusions of security – and their sense of place within Pakistani society – came crashing down: the Governor of Punjab, Salmaan Taseer, was shot and killed by one of his own bodyguards, on grounds that he had the audacity to suggest that there may have been a miscarriage of justice against a woman accused of blasphemy.

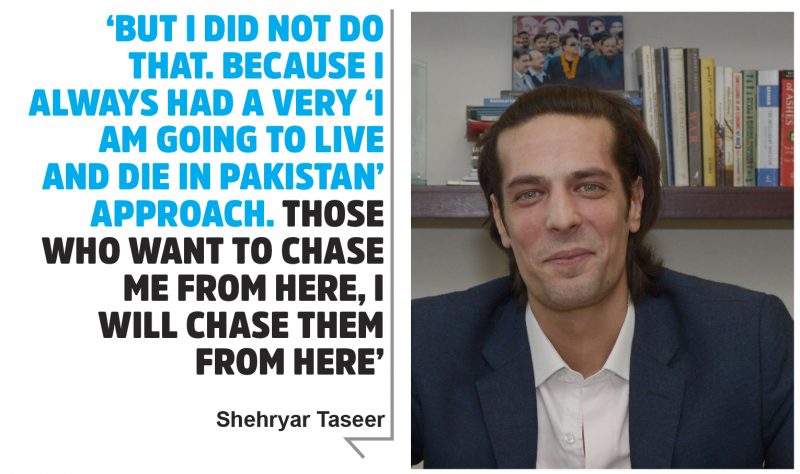

Shehryar Taseer remembers that day more clearly than just about anyone else: the man killed was his father, and the day was his 25th birthday.

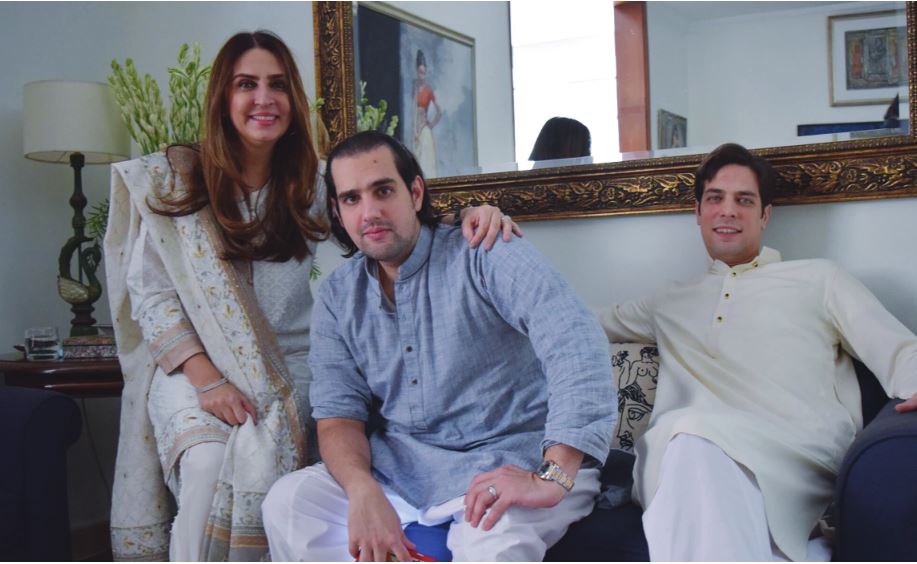

“I was with him [that day] in our house in Kohsar Market in Islamabad. Just 30 feet from my house, where I was sitting, on my birthday, my father was assassinated,” said Shehryar, in an interview with Profit.

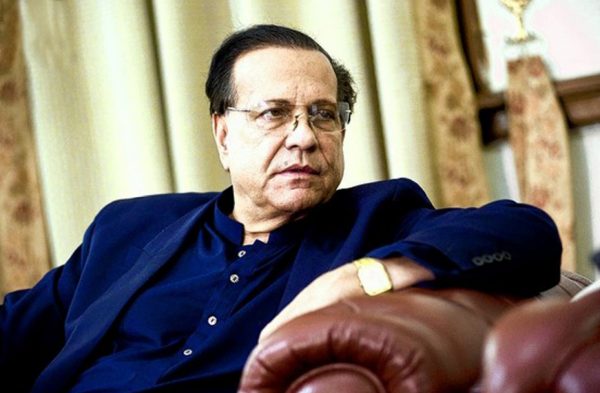

Before he was killed on that day, before he became a politically active Governor of the country’s largest province, and long before he gained his Twitter following, however, Salmaan Taseer was an icon in Corporate Pakistan, and the founder of a collection of businesses that were known to punch above their weight in terms of economic significance.

The elder Taseer will indelibly be remembered for his political legacy, and justifiably so. But lost in the conversation about the shocking nature of his assassination is the reason behind the shock: he was a very wealthy man, and not even from the “wrong” ethnic or religious groups. Men like him are supposed to be immune from the slings and arrows of daily life in Pakistan, protected by the walls that their wealth affords them. Taseer had the added protection of being the governor. But in the end, none of it was enough.

This is the story of how Salmaan Taseer acquired that wealth in the first place. And the story of what happened to that fortune after his assassination.

The poet’s son becomes a quant

The elder Taseer was born in 1944, and grew up in a multicultural, literary home. His father was Mohammad Deen Taseer (famously known as M.D. Taseer) and his mother was Christobel George, a British leftist activist who later changed her name to Bilqis. His mother’s sister was Alys, who was married to legendary poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

Taseer’s father died in 1950 at the age of 47, when Taseer was only six years old. He was raised primarily by his mother and went to St Anthony’s School in Lahore, and then on to Government College Lahore (at each of these institutions, he was only a few years ahead of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif).

Following his graduation from Government College, Taseer went off to London to study that most middle-class of subjects: accounting. He became a chartered accountant in England, and rose through the ranks of accounting firms within the UK enough to feel confident about starting his own accounting firm in the 1970s in Pakistan and the UAE.

The firm he founded, Taseer Hadi, would partner and become a member of one of the largest accounting firms in the world, KPMG. KPMG Pakistan is still known as KPMG Taseer Hadi & Company.

It was an opportune time to set up an accounting firm, since the Gulf Arab states were beginning to develop formal economic institutions, and thus would need accountants. Pakistan had an older established tradition of both accounting and corporate institutions, but the 1980s brought a revival of the need for such firms after a boom in private sector activity took off.

By the early 1990s, Taseer felt confident enough to wade into other ventures. One of his earlier such ventures was Pace Pakistan, a residential and commercial real estate company established in 1992 and still listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. In 1994, he created First Capital Securities, a stock brokerage firm that was briefly affiliated with US brokerage firm Smith Barney.

In 2001, he created Media Times, a company that now publishes two daily newspapers (the left-leaning English-language Daily Times and the Urdu-language Aaj Kal), two magazines (Sunday Times and TGIF) as well as two television channels, the business-focused Business Plus and the food-centric Zaiqa TFC.

It was not until 2001, however, that Taseer created his biggest business: Worldcall Telecom, which was a cable television and broadband internet services provider, and at one point was the largest such company in the country before the state-owned Pakistan Telecommunications Company (PTCL) awoke from its slumber and crushed all competition.

To have gone from being the partner at what started out as a small accounting firm to being the owner of an empire that encompassed several publicly listed companies across a wide array of industries is an entrepreneurial run to marvel. At the time of his death, Shehryar Taseer estimates that his father’s net worth was around $800 million, easily making him one of the wealthiest men in Pakistan (and, really, anywhere in the world, come to think of it).

The empire at Salmaan’s death

A large chunk of that money was no doubt from the sale of the family’s 60% stake in Worldcall, which was sold to Omantel in a transaction worth $210 million at the time it was executed in April 2008. Where that money was reinvested is not entirely certain, however, as Salmaan became Governor Punjab the next month, in May 2008, and appears to have largely stopped exercising direct control over any of the companies he owned.

The Taseer empire since then, at least publicly, appears to have shrunk considerably, with just Media Times, Pace, and First Capital left as the publicly listed parts of the family’s businesses. The total market capitalization of the family’s major publicly listed companies (and not just the family’s share in those companies), as of the close of Friday’s trading on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, stands at Rs2.9 billion ($30 million).

The Taseer family is likely still one of the wealthiest in Pakistan, but the publicly listed part of their wealth appears to have shrunk considerably. The reasons for this shrinkage are not simply that the company lost its founder.

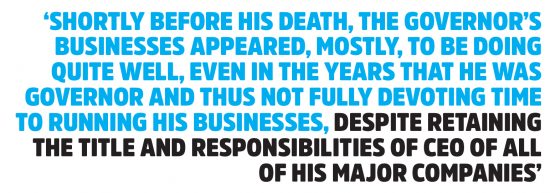

Shortly before his death, the governor’s businesses appeared, mostly, to be doing quite well, even in the years that he was governor and thus not fully devoting time to running his businesses, despite retaining the title and responsibilities of CEO of all of his major companies.

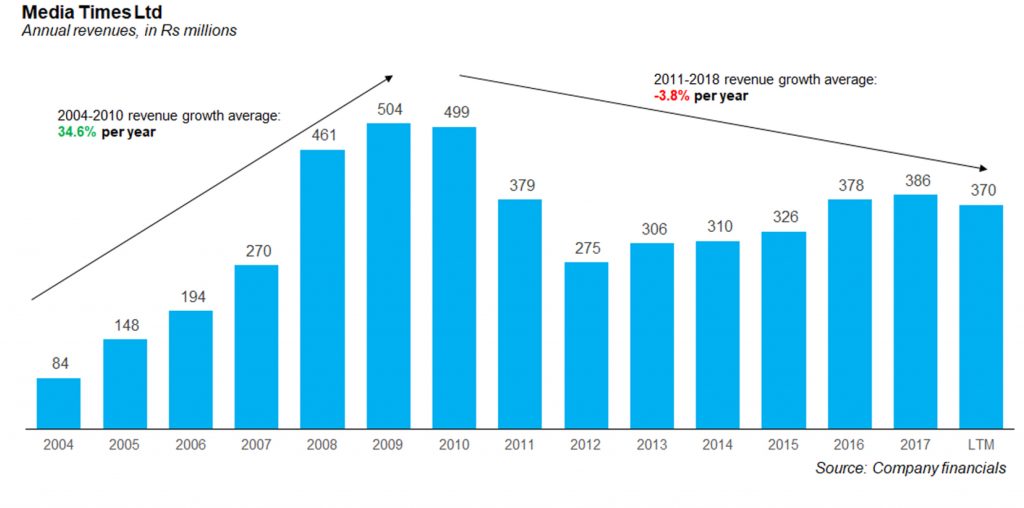

Media Times, the newspaper and television business, appeared to be making significant traction with respect to revenue growth (although cash flow health did not always match sales growth). Revenues had grown to Rs500 million in the financial year ending June 30, 2010 (all Taseer companies end their financial years on June 30). This represented an average annualized growth rate of 34.6% since 2004.

The group’s securities brokerage firm – First Capital – also had a remarkable run in years immediately preceding the governor’s assassination, with revenues rising by an average annual growth rate of 24.8% per year in the six years leading up to fiscal 2010. Most impressively for a financial services company, First Capital actually saw an increase in revenue in the years immediately following the global financial crisis of 2008, suggesting that the firm was remarkably resilient.

The biggest of the group’s businesses by revenue was the real estate arm, Pace Pakistan. Pace was, at the time, one of the largest real estate developers in Pakistan, and for a long time, the only one that was publicly listed. Though it had a strong residential real estate arm that developed both houses as well as apartments, the bread and butter of the company was middle-tier shopping malls, which it developed in cities all across Pakistan.

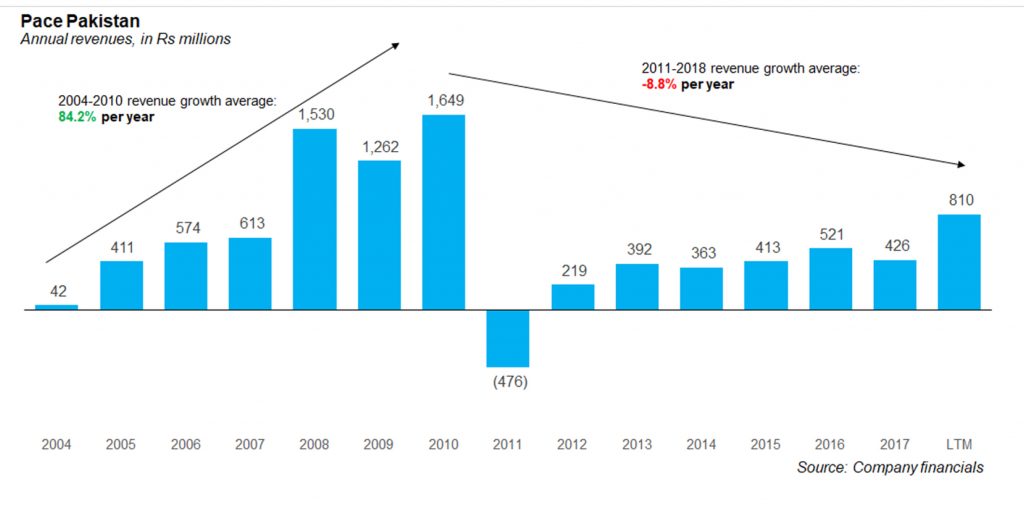

In the six years prior to Taseer’s assassination, the company had been doing remarkably well, growing revenue by an astonishing 84.2% per year on average between fiscal 2004 and 2010. In the three years before Salmaan’s death, the company consistently registered revenues exceeding Rs1 billion.

The financial cost of opposing blasphemy?

All of that progress came crashing down in 2011. The Taseer family paid a heavy price for Salmaan’s stand against the abuses of Pakistan’s blasphemy law (the governor had always made it clear that he opposes misuse of the law, not the law itself). And the price was not just in blood.

Less than one month after Salmaan Taseer’s assassination, the Taliban kidnapped his son Shahbaz Taseer, and kept him imprisoned for the next five years, until 2016. That emotional anguish, by all accounts, was devastating to the family, particularly to Shahbaz’s mother, Aamna, who had served as her late husband’s second-in-command on the boards and management committees of the family companies.

And so, the task fell to young Shehryar Taseer to manage the businesses and keep the family financially afloat as they dealt with the emotional agony of the assassination and the kidnapping. As shaken as they were, Shehryar states that they never thought of just selling it all and leaving the country.

“When my father died, when I liquidated, even if I took a negative assessment of 30%, I would say I would easily walk away with several million dollars that will see you through life. But I did not do that. Because I always had a very ‘I am going to live and die in Pakistan’ approach. Those who want to chase me from here, I will chase them from here.”

That decision to stay, however, came with costs. It soon became clear that the ideology that led people to murder the governor was far more widespread than his assassin (as if the pictures from the trial and subsequent funeral of the assassin were not enough proof already).

Every single one of the Taseers’ companies saw a sudden and sharp drop in revenue in 2011, and continued to see tremendous declines in revenue for the following several years before eventually stabilizing.

Here are the numbers: in the six years prior to the governor’s death, Media Times revenues grew at 34.6% per year; in the years since then, revenue growth has actually swung negative to -3.8%. With the paper facing increasing competition ‘Sunday Magazine’, their weekly fashion magazine, became an important revenue contributor. What began predominantly as a magazine carrying pictures of the who’s who of the week’s social events and parties started getting the attention of retailers looking for advertising space that was cheaper than the newspaper’s prime ad space. The industry of weekly magazines that was essentially founded by Daily Times ‘Sunday’ has now become a cash cow for other publications as well all of whom have ridden the retail boom through their respective weekly’s. It was a lucky break for the fledgling media group coming just at the right time.

For First Capital, the numbers are 24.8% per year in the six years prior to the assassination, and -6.7% per year since then. And for Pace Pakistan, the numbers are most dramatic: that 84.2% per year annual growth rate swung to a -8.8% per year annual contraction since the murder.

It was not just the men with the guns who came for the Taseers. It was the polite upper and middle class people who quietly decided to take their business elsewhere.

Overnight, the Taseers became pariahs in their own home.

For some of these businesses, it may be possible to explain away the results for other reasons. Daily Times, for instance, saw a decline in revenue right when Pakistan Today and The Express Tribune were beginning to pick up steam as competing English-language newspapers in Pakistan.

And First Capital Equities, by virtue of its exposure to the capital markets, is by definition in a volatile industry that can cause wild swings in revenues.

But Pace Pakistan struggled when real estate in Punjab was going through a boom. The business found both credit and customers hard to come by that year, and actually ended up with negative revenues in 2011 as it was forced to cancel orders from customers who were not paying up their requisite installments and return their money.

And it was not even the people who bought things from the Taseer-owned businesses. Even companies whom the family’s businesses paid money to perform services started to refuse to do business with the company.

“Our auditors didn’t want to audit for us anymore, because they had mullahs inside their firms who said that we don’t believe in khatm-e-nabuwat (finality of Prophethood),” said Shehryar. “What does saying anything about the blasphemy law have anything to do with khatm-e-naboowat? But people said such stuff about us and, at that time, staying alive was a very big achievement.”

That collapse in revenues, at least part of which may have been the result of the social boycott of the family, in turn caused other problems. The company began having trouble paying off its debts, since lower revenues meant lower cash flows available to make debt repayments.

“I had Rs18 billion in debt that I owed to the banks, I had no income, all my companies were in operational loss, I had no inheritance, no cash flows, all my companies were in operational loss in my father’s life. But I did not let anything shut down,” said Shehryar.

The debt repayments alone would not have been a problem if the family had been able to turn to their co-investors and longtime business partners for capital injections in businesses that had, until recently, been strong money spinners. But the social boycott – this one perhaps unintended – extended to people who had gladly been willing to do business before.

“Every investor in my group turned away and left, everyone who was associated with my business group wanted to disassociate themselves because they were scared that they will get killed,” claimed Shehryar, offering a rational explanation.

A dispute over inheritance

It was not just outsiders who were causing problems for the Taseers, however. The family was split even among themselves, in large part over the question of the inheritance, particularly the question of who should get the title of publisher of Daily Times, an asset that the family felt a lot of emotional attachment to.

Under Pakistani law, while the ownership of a newspaper can belong to any individual or any form of corporation, the title of publisher, and ownership of the name and masthead of a daily newspaper, can only be owned by an individual, and not a company.

This has the effect of making the act of publishing a newspaper more personally liable than any other form of business, but it also creates problems at the time of inheritance: Salmaan Taseer’s shares in Media Times Ltd can be split up between his hiers in accordance with his will or inheritance law, but the title of publisher, and thus ownership of the newspaper’s brand, can only go to an individual, which complicates the process of deciding who gets to inherit the title. Given the fact that Daily Times is published from multiple cities, and that the publisher title is separate for each city, the problem is not insoluble, but it does require consensus among the heirs.

This is where the heart of the dispute starts.

Salmaan Taseer has seven children, six of whom are Pakistani citizens: Shaan, Sara, and Sanam are the children of his first wife Yasmeen Sehgal, and Shahbaz, Shehryar, and Shehrbano are the children of his second wife Aamna. The seventh child, Aatish, is the son of Tavleen Singh, an Indian journalist with whom Salmaan had a brief relationship.

After the governor’s death, there emerged significant differences between the children of his two wives. While family matters are rarely simple, the legal dispute at least pits Yasmeen’s children against Aamna’s.

Sara ha not only filed claims against her half-brother in court, but has waged a very public battle on social media, attempting to draw attention not just to what she feels is unjust distribution of family resources, but also what she feels is mismanagement of the newspaper on the part of Shehryar.

For his part, Shehryar states that Media Times as a business faces external challenges that would be difficult to control for just about anyone. In recent years, Daily Times has received flak on social media for not paying the salaries of its staff on time, and Shehryar in particular has come under personal criticism for those delays (even though the salary delays were at their peak in 2009-2010).

Shehryar acknowledges the frustration of his staff, but points out that the matter is not entirely in his control. He focuses on the role of advertising agencies and media buying houses in creating cash flow problems for newspapers and other media companies, laying the blame squarely on the company Midas, one of the largest media buying houses in Pakistan.

“These advertising agencies will kill us all,” he said. “The government [largest advertiser in Pakistani newspapers] has to pay me Rs280 million and the government says that it is payable by Midas. Midas says that the government has to give it… And our total market payable is Rs20 million. In this, I have endured such abuses on staff [salary] payments. This happened with everyone in the industry. This circular debt was simply created because of Midas. They would bag government money, eat it up, and not release it to the staff. It’s the end of the month, and the staff want their salaries. Midas give us checks, the checks bounce, and the owner of Midas is suddenly in London. He is in jail, and even if the check bounces what can I do? He is already in jail.”

Comeback in the offing?

Albeit Media Times’ broadcast business struggling, for its part, Daily Times appears to be in good hands under Raza Rumi, a left-leaning former civil servant turned journalist who himself was attacked by the Taliban in 2014 and had to flee to the United States for fear of his life.

And both Pace Pakistan and First Capital Equities appear to have had significant revenue growth over the past couple of years, though neither company is anywhere close to coming back to the levels of revenues they saw when Salmaan Taseer was alive.

Climbing out of the hole society puts you in for opposing the blasphemy law takes a long time, apparently, but if the budding recovery of the Taseer family businesses is any indication, it at least looks like it might be possible.

Good luck Shehryar!

Well written!

Tragic moments for taseer family…

May God bless you Dear , You and the family suffered a lot

That is why it is said Businessman should never join politics………… By now Salman Taseer would have been the richest businessman in Pakistan !!!

Comments are closed.