The last two months have been bizarre, to say the least. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the global economy to a halt, and Pakistan along with it. The nationwide lockdown has been extended until mid May, leaving almost everything minus the country’s food supply and grocery stores on hold.

In the midst of this pandemic, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has taken drastic actions, cutting the benchmark interest rate by 75 basis points one week, 150 basis points the next week, to 11%, and then 200 basis points to 9% just three weeks later. (One basis point is one-hundredth of one percentage point.) It has also announced a flurry of relief packages and loan relaxations to borrowers and exporters, in an effort to assuage their financial concerns.

Because the pandemic is so unpredictable, and the government and the State Bank’s responses similarly so rapid, it can be difficult to make sense of what is going on. Even a cursory glance at Profit’s comments section reveals a litany of bewildered responses, some confused and others even indignant. However, one in particular stood out.

Commenting on an article titled “SBP allows one-year moratorium on consumer loans’ principle,” S. Asrar Ali had the following to say:

“Regarding recent decrease in key interest rates by the State Bank of Pakistan which was a surprise as we see prices of all other things that are dollar, gold, commodities, gas & electricity bills etc going constantly up. Hence the interest rates whatever were needed to be enhanced rather contrarily declined.

The funds in banks are public hard earned savings and not the property of the government or SBP and need to be given appropriate return in the form of interest to cover ever increasing all round prices and maintaining purchasing power of their rupee holdings in banks. Instead giving a decrease in interest to those who borrow from banks out of saver funds for facilitating ever increase in prices of their commodities at the cost of victimising saver is sheer injustice.

The Government or the state bank thus don’t own the funds in banks have no right to decrease interest particularly when prices of everything go up and should reverse the decision by fixing interest rates at 25%.”

The uncharacteristically long comment resulted in a back and forth between reporter and editor over whether the reader had a point. And while the conclusion was that the comment in question did not quite have its bearings right, it did raise a few important questions. FAQs, if you will, that Profit thought might be important to answer.

Fundamentally, there are three questions being brought up here:

- Why did the SBP decrease the interest rate if the prices of commodities are increasing?

- Why is the SBP giving a preference to borrowers, instead of savers? Does that not erode the savers’ gains?

- Why does the State Bank have any right to change interest rates to begin with, if it does not own the funds in a bank?

Profit will attempt to answer these three, pertinent questions.

- Why did the SBP decrease the interest rate if the prices of commodities are increasing?

The State Bank changes the interest rate, with one eye out at all times for the inflation rate. The inflation rate is measured monthly by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). In Pakistan, as in most countries around the world, inflation is measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which comprises both urban CPI and rural CPI. The current base year is the fiscal year ending June 30, 2016, meaning prices are measured relative to what they were that year.

The urban CPI covers 35 cities and 356 consumer items, while the rural CPI covers 27 rural centres and 244 consumer items. The CPI looks at essential items for all Pakistanis (not the prices of gold or commodities), but the prices of goods like food, housing, electricity, gas, and fuel.

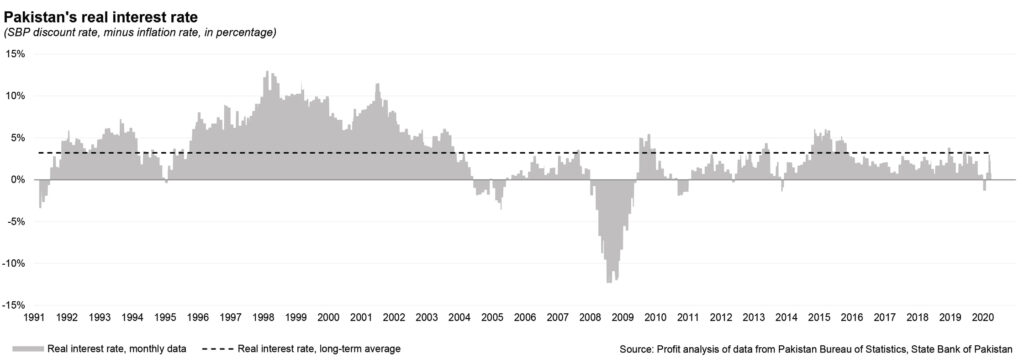

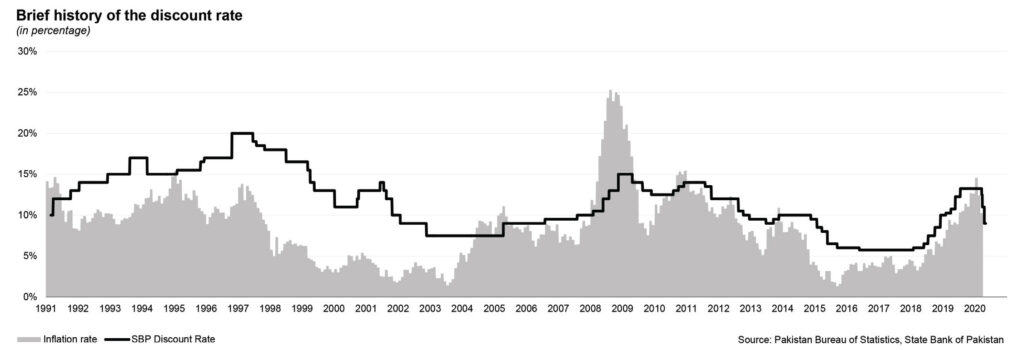

It is true that the prices of these goods rapidly rose in the last year. At the start of January 2019, the inflation rate was recorded at 5.6%, meaning prices rose on average by that much compared to the same month in the previous year. It stayed in single digits until August 2019, when the inflation rate was recorded at 10.5%. It then hovered between the 11-12% range from September to December 2019, before climbing to 14.6% in January 2020.

But then, in February 2020, something interesting happened. The inflation rate actually fell to 12.4%, and then fell further to 10.2% in March 2020. And according to the State Bank, the average headline inflation is expected to remain within the 11-12% forecast in fiscal year 2020, before falling to the medium-term target (in two years) range of 5-7%.

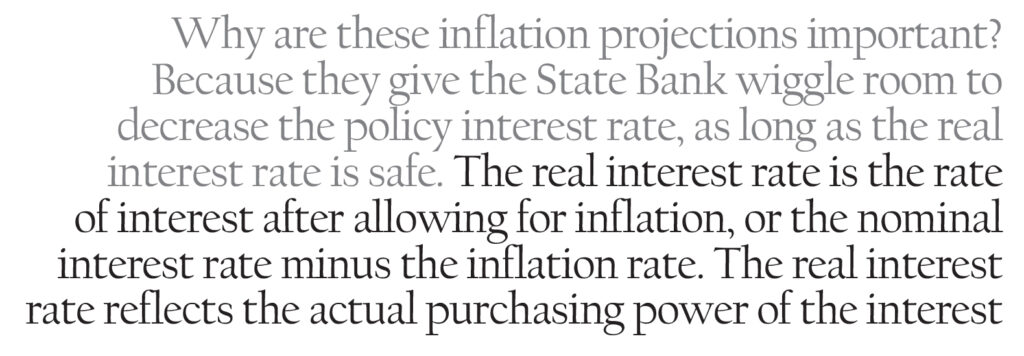

Why are these inflation projections important? Because they give the State Bank wiggle room to decrease the policy interest rate, as long as the real interest rate is safe. The real interest rate is the rate of interest after allowing for inflation, or the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. The real interest rate reflects the actual purchasing power of the interest. In economics parlance, this equation is known as the Fisher effect.

Under the conditions set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the SBP must maintain positive real interest rates, and so far, it has been working. One can calculate this for any month; in March, this is 11% minus 10.2% or 0.8%. The real interest rate in Pakistan for the second half of 2019 was around 1 to 2% (13.25% minus 11% or 12%).

Why does the IMF mandate this? Because it believes, like our commenter, that savers should be given a return over and above the inflation rate as a fair rate of return, to incentivise them to put their money in bank accounts or other fixed income investments. Otherwise, it would be tantamount to them losing the real value of their money.

To be fair, the current real interest rate is not exactly great. The State Bank Governor, Reza Baqir, has previously said that historically in Pakistan, the real interest rate has hovered slightly higher, at around 3%. He may be referring to the long term average since 1991, which has been around 3.2% during the nearly three decades for which discount rate data is available, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the SBP and PBS..

But as long as the SBP can make sure the real interest rate is positive, by looking at the prices of what the PBS sends out every month, then it is allowed to comfortably decrease interest rates, should it choose to.

- Why is the SBP giving a preference to borrowers, instead of savers? Does that not erode the savers’ gains?

Any monetary policy decision will always have some winners, and some losers. In decreasing the interest rate, this will surely affect the interest rate that savers have been receiving, particularly in the climate of extraordinarily high interest rates in 2019.

Keep in mind that at the start of the 2019, the policy rate was only 10%. Subsequent policy reviews – in January, March, May and July – increased the policy rate by a total of 325 basis points to 13.25%. At the time, it was the seventh-highest policy rate in the world, well above the world average of 6.38%.

[Also, Pakistan’s policy rate has always been on the higher side. Between the period 1992 and 2019, the highest policy rate was set at 20.0%, and the lowest at 5.75% – not that that has particularly created a culture of saving in Pakistan, but that is a different story.]

The year 2019 was an incredibly lucrative time to save. But, as the Prime Minister also keeps saying to justify his ‘smart’ lockdown, decisions have to be made for the economic well being of 200 million Pakistanis, not just savers.

Take a look back at the inflation numbers in our first answer. The numbers are going down, but why are they going down so rapidly? Well, aggregate demand has actually fallen, and there is a danger of it collapsing. The pandemic means that global demand for imports, (even low quality Pakistani exports) has fallen, and locally, the lockdowns, and subsequent layoffs, have severely affected people’s spending power.

In drastically cutting the interest rate, and introducing appealing schemes for exporters and borrowers, the SBP is saying it wants to keep demand alive, and make sure that Pakistanis still buy items, and the country still manufactures them.

This is a real concern because the pandemic is not like any other financial crisis. In the monetary announcement on 17 March, SBP governor Reza Baqir dryly noted, “Fundamentally, we are dealing with a disease.” Even if interest rates are cut, people will not take the risk of leaving their houses and contracting the disease by standing in a store. And even if they wanted to shop, when will stores reopen? The new SBP measures are a hope against hope to keep Pakistan’s economy afloat. Savers will just have to wait.

- Why does the State Bank have any right to change interest rates to begin with, if it does not own the funds in a bank?

This is one of the most interesting ideas that needed to be wrangled with. It essentially asks, does the State Bank have any right to operate the levers of the economy like this? Really, it is a fascinating concept, and borderline libertarian. We have all grown up hearing the State Bank change the interest rate to this or that, but who in the world bestowed this unelected body with this authority?

There are two ways to answer this: the historical rise of the central bank, and the practical reason for a central bank (which clears concepts of ‘ownership’).

Why do we have central banks? They are a relatively new concept having only been around for a few hundred years or so. Most of these precursor banks were started in the late 1700s or 1800s in Europe, to finance wars for governments.

The modern central bank is a much more recent phenomenon. As an example, let us look at the United States. It had regular and severe bank panics through much of the 1800s, which would frequently cause banks to collapse.

However, there was a particularly severe panic in 1907, when thousands of people scrambled to withdraw their money from banks, leading to massive bank runs and banks across the US declaring bankruptcy. The financier John Pierpont Morgan (yes, the person who started JPMorgan, now the largest financial institution in the world) had to literally step in and act as the banker of last resort, to shore up the banking system.

Realizing that an individual had to step in, the US government enacted the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which created the Federal Reserve System – or the US central bank. [Incidentally, J.P. Morgan died just a few months before the Federal Reserve was created, prompting much commentary that now that he was dead, the US government needed to create a central bank to replace him.]

This, by the way, is a good example of one of the key features of a central bank: a lender of last resort that provides emergency credit to financial institutions. If banks no longer have other means of borrowing, and if a severe bank run dramatically affects the economy, that is when the central bank steps in.

This ushered in a period of the creation of central banks, as countries around the world recognized the importance of central banks. Australia established its first central bank in 1920, Mexico and Chile in 1925 and Canada and New Zealand in 1934.

South Asia is no exception. The precursor to the State Bank of Pakistan was the Reserve Bank of India, which was created in 1935 in colonial India, mostly because of financial troubles in India due to the First World War, and the Great Depression which followed it. The Reserve Bank of India continued to be Pakistan’s central bank even after Partition, until 1948, when the State Bank of Pakistan was set up.

Under the State Bank of Pakistan Order 1948, the bank’s duties were to “regulate the issue of Bank notes and keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in Pakistan and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage”.

But eight years later, the bank’s duties, responsibilities and role were all expanded significantly. Under the 1956 State Bank of Pakistan Act, the bank now had to “regulate the monetary and credit system of Pakistan and to foster its growth in the best national interest with a view to securing monetary stability and fuller utilisation of the country’s productive resources”.

In India and Pakistan, and South Asia in general, we have had historically more “involved” central banks, due to the legacy of the Reserve Bank of India, which initially financed development projects.

On the SBP’s website, it clearly states that “The responsibility of a Central Bank in a developing country [emphasis mine] goes well beyond the regulatory duties of managing the monetary policy in order to achieve the macroeconomic goals. Ever since its establishment, the State Bank of Pakistan, besides discharging its traditional functions of regulating money and credit, has played an active developmental role to promote the realisation of macroeconomic goals”.

Pakistan embarked on a series of financial reforms in the 1980s, which led to reforms in the central bank in the 1990s. First, the State Bank of Pakistan was granted autonomy in February 1994. Then in February 1997, Parliament passed three amendment ordinances to the State Bank of Pakistan Act 1956, the Banking Companies Ordinance of 1962 and the Banks Nationalisation Act of 1974, which in total, granted sweeping autonomy and authority to pursue an independent monetary policy. The State Bank of Pakistan as we know it, with all its powers, monetary policy committees (MPCs) and ability to control the levers of Pakistan’s economy, is a phenomenon of only the last couple of decades.

This leads us to point two: the practical reason to have a central bank. For starters, the bank is a regulator, which means it can whip into shape private banks in the country, and can dictate how much banks can lend to customers, or how much cash they have on hand, though reserve requirements. And as discussed already, the central bank can provide loans to a country’s private banks, as the lender of last resort.

These loans lent as a last resort are interesting. The central bank sets the policy rate, which is the rate at which commercial banks can borrow from the central bank. This then influences the rate at which banks can lend money to one another. The average rate of lending between banks is known as KIBOR or the Karachi Interbank Offered Rate. Private banks then use KIBOR as a reference and structure their loans to borrowers accordingly.

That is how the policy rate ends up indirectly controlling the amount of private borrowing, and subsequent spending, in an economy.

Commercial banking – that is, customers depositing money, and banks lending out a portion of that money out to other customers – is one event. A private bank getting a loan from the central bank – the central bank acting as the ‘lender of last resort’ – is another event. The two are not directly related. So how come it is the central bank that gets to decide the interest rate that private banks give out loans at?

Well, the central bank gets to do this because of its mandate: securing monetary stability. On the State Bank’s website, it clearly states that the central bank bank defines monetary stability as “ the best way to achieve these objectives on a sustainable basis is to keep inflation low and stable. Low and stable inflation provides favorable conditions for sustainable growth and employment generation over time.”

This is kind of what the previous two answers discuss, that the SBP manipulates the interest rate in order to keep inflation in check. This is actually known as Taylor’s rule, which states that interest rates should change as the economy shifts. So higher interest rates when inflation is high, and lower interest rates when inflation is low.

Think of the interest rate as a moving target that the SBP can control. It has to be high enough so that savers can deposit money in the bank, and low enough that borrowers can take out money.

Private banks cannot escape the interest rate that the central bank sets, and arbitrarily set their own interest rate. The policy rate is a signal to the entire economy. That policy rate determines how many deposits a private bank is getting. That rate influences the KIBOR, or the rate at which a private bank can get a loan from another private bank.

The rate also determines how much interest the private bank itself is getting on its reserves that it has parked with the central bank. Under the SBP’s Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR), private banks must keep a portion of their rupee and foreign currency deposits with the State Bank. A private bank will not keep the rate at which it lends to private borrowers at a lower interest rate than the one set by the State Bank. Were that to happen, the bank would always be incentivised to just not lend, and keep its deposits parked. Instead to make profit, it sets it at a higher interest rate than the policy rate.

This makes the interest rate an extremely important lever at a central bank’s disposal, one that has an outsize impact on a country’s economy. To again use an example from the US: in the late 1970s the US experienced out of control inflation, reaching 14.8% in March 1980. Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve chairman at the time, decided to increase interest rates to double digits, the idea being that it would constrict borrowing and spending, thereby leading to a decrease in price inflation. The interest rates were so high, that it actually led to a recession in 1982. However, once the interest rate was relaxed a little in 1982, the higher interest rates had the desired effect: inflation decreased to less than 3% by 1983.

Something similar happened in Pakistan during the Zardari Administration, with slightly different consequences. Shahid Kardar became State Bank Governor in September 2010, a time when inflation was stubbornly high. He raised interest rates twice, once in September and again in November 2010, a move that did not go over well with the President and the Finance Ministry. Rather than letting him continue as head of the central bank, however, they created conditions that forced him to resign in July 2011. Inflation remained high for nearly the entirety of the Zardari Administration, which ended in May 2013, and did not come back down to single digits until two years after Kardar’s resignation.

So yes, the State Bank does get to control interest rates, and it does so in order to fulfill its mandate, provided to it in 1956 to “secure monetary stability and fuller utilisation of the country’s productive resources.”

Now, as to the more granular point of S. Asrar Ali about owning funds, let us move with a hypothetical. Let us say he deposits Rs1,000 in a private bank (we’ll call it Karachi Bank). He has every right and ownership over the Rs1,000 that he has deposited in the Karachi Bank, and can withdraw the money at any time. But he has no ownership or right over the interest rate that he is accruing on those Rs1,000. That just happens to be a by-product of the deposited Rs 1,000.

Whether the interest rate happens to be really high one year (as it was in 2019), or really low the next year, it is not Ali’s right. The only way the interest rate caters to Ali, is that it must be high enough to incentivize him to deposit his Rs1,000 in the first place.

In fact (to tie it back historically), by depositing his money in Karachi Bank, Asrar Ali is a member of the modern banking industry. He is not only entrusting Karachi Bank with his money, but is also confident that Karachi Bank will be saved in the event of a bank run, by another, larger bank, which will naturally be the central bank.

The central bank’s existence and ability to lend out money at certain interest rates to private banks like Karachi Bank, is what gives Karachi Bank the confidence to lend out money to citizens. This fragile system, based on money, trust, and interest rates, is what we have had in Pakistan, technically since 1935, more than a decade before we even had a Pakistan to talk about.

And if the interest rates are not of a particualar saver’s liking, what S. Asrar Ali could do, to make life more predictable, is to realize that instead of keeping money in a savings account in a volatile developing country like Pakistan, it would be more prudent to strategically deposit money in a fixed deposit account, where the return is more stable. Problem solved.

The article forgets to mention the main reason the country is so starved of capital – real interest rates are too low. There’s little incentive to save money here.

COVID-19 pendemic is a global issue people are suffering particularly low income members of society are even unable to earn the livelihood for survival in such a situation the above article is a slap on the face of humanity, state Bank of Pakistan issued directives to the banks to facilitate low income borrowers. Now is the time to save humanity not money. Atleast instead of writing these sort of article to please Private banking maafia write for the betterment of mankind and to uprise the humanity and charity. If you thing your are genius suggest policy measure rather this sort of criticism.

انداز بیان گرچہ بہت شوخ نہیں ہے

شاید کہ اتر جائے تیرے دل میں میری بات

I hope you do realize that the number of savers who have deposited money in saving or fixed income accounts is far larger in Pakistan than the ‘borrowers’ from low income group. If you are not aware let me tell you something, the banks do not give loans to low income borrowers in the first place. They are influential and powerful Corporations or big businesses usually. A very small % of population avail consumer financing. However, the amount of deposits by Consumers in Saving and Fixed income accounts far exceeds that of loans availed by Consumers (more than 20 times!). All these savers, who are mostly retired individuals with no other source of income stands to lose with reduction in interest rates. So if you talk about humanity, interest rates should be increased to facilitate larger population, rather than reduced to benefit the capitalist society and the large corporations!

Nice article. I know many savers who were basically retired individuals that run their household expense on the interest (or profit) earned on their life long investments in deposits. Now while their expenses are increasing, the income has been reduced considerably due to decrease in interest rates. Banks have reduced rates of both savings and fixed deposit accounts and more reduction is on the cards, so they have been left with little to cover up their monthly expenses.