Let us get one thing straight: the government’s deals with the independent power producers (IPPs) – announced with much fanfare last week – are impressive: if the memoranda of understanding (MoUs) are converted into legally binding contracts signed by all sides, the government will have renegotiated deals to become significantly more favourable for itself. So, we do not mean to diminish the significance of the agreements themselves.

We do, however, want to disabuse our readers of the notion that these agreements will have any material impact on load shedding (as we collectively refer to regular power outages) nor on the reliability of the electricity grid. The rot will continue exactly as before, because the problem in Pakistan’s energy grid is not – and has not been since the 1990s – in the power generation sector.

No, the core of the mess at the heart of the country’s energy infrastructure is in the one part the government does not have the audacity to try to fix: rampant theft that plagues the transmission and, much more importantly, distribution of electricity in Pakistan.

This is not a matter of opinion. It is objective reality that absolutely everyone who has studied the energy sector agrees upon: fixing theft is several orders of magnitude more important than fixing whatever issues exist in the power generation sector.

According to the March 2020 “Report on the Power Sector”, compiled by the government’s Committee for Power Sector Audit, Circular Debt Resolution, & Future Roadmap, reforms in the power purchase agreements similar to the ones the government has agreed to with the IPPs – if implemented across the entirety of the power generation sector (and the recent agreements cover only part of the IPP sector) – could reduce electricity costs to consumers by as much as Rs1 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), the basic unit of electricity purchase.

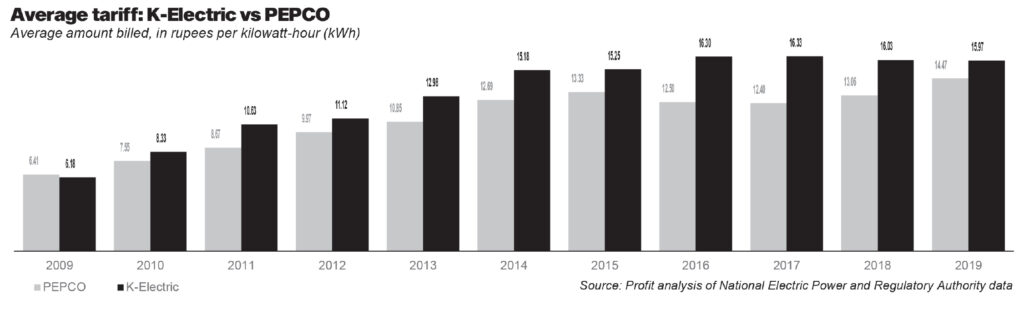

Data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) suggests that the average cost of electricity sold in the country was approximately Rs14.47 per kWh in fiscal year 2019, the latest year for which complete data is available. So a Rs1 per kWh reduction in the price of electricity is not unsubstantial.

Here is the problem, though: according to Profit’s calculations based on NEPRA data, theft of electricity and defaults on electricity bills raise the costs of electricity to bill-paying customers by Rs4.52 per kWh. (More on how we make those calculations below).

It is not even close: the reason electricity in Pakistan is expensive is because Pakistanis steal electricity much more than even comparably developing countries. Until the government cracks down on theft, trying to fix load shedding will be like trying to heal a sword wound with a Band-Aid: it might cover a very small part of the wound, but unless you use something more suited to the task, the patient is likely to bleed to death.

In this story, we will examine the history of power generation and distribution in Pakistan, how the industry has evolved over the past six decades, including how IPPs came into being, and examine how we got into this mess. We will look at the series of bad ideas that have plagued the government’s attempts to fix the energy grid, and how the government keeps digging itself into a bigger and bigger hole.

The IPP policies

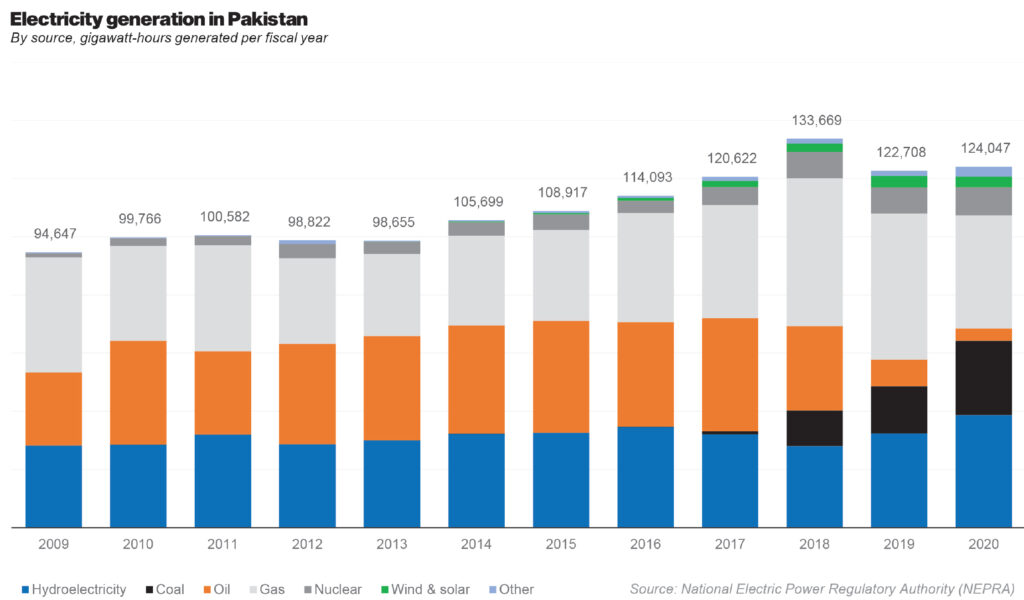

The story starts from the mid-1980s, when Pakistan’s economy first started growing beyond the ability of Tarbela and Mangla dams’ hydroelectric power production capacity, and when the World Bank suggested that Pakistan should start encouraging private sector investment in power generation. While the history of electricity generation in Pakistan starts with private companies, most of those were nationalised in the mid-1950s, long before Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became Prime Minister.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, Pakistan’s economy stood at a peculiar place. The old industrialist and wealthy families had seen their fortunes decimated by the nationalisation policies of Prime Minister Bhutto in the 1970s, but the new industrial elite – the one that currently dominates the economy – had not yet amassed the levels of capital that they have today.

As a result, the government’s policies to attract investment – and the World Bank’s recommendations on the matter – were geared mainly towards attracting international investors to the sector. This was a legitimate policy goal at the time, since the first Pakistani IPP – the Hub Power Company (Hubco) – was indeed the result of investment from European electricity companies.

As discussed in our story on Hubco in December 2019, the incentive structure offered by the government was therefore geared towards foreign investors: returns guaranteed to be indexed to the US dollar rather than the Pakistani rupee, and inflation-indexed to US inflation rather than inflation in Pakistan.

We will not delve into details as to why we argue that those incentive structures are not as excessive as they sound – at least as formulated – except to say that when they work properly, those dollar-denominated returns account for between 4% and 6% of the cost of producing one unit of electricity.

And since the government was seeking to effectively add excess capacity through the use of these IPPs, the choice of fuel was furnace oil. The reason for this is that oil-fired power plants are easy to quickly turn on and off, compared to coal or gas-fired power plants which take a little longer to get started and are best run when they are running all the time or almost all the time.

The 1994 policy originally offered a 17% guaranteed return on equity to investors, though the Musharraf Administration negotiated this down to 12%.

Solving the wrong problem

What happened next should have been predictable: the government never adjusted its policies to changing realities. In the 1990s, there were very few domestic industrial groups that had the capacity to set up large scale power projects, which is why offering incentives geared towards foreign investors was necessary. But by the early 2000s, this had changed.

Several of Pakistan’s larger conglomerates were interested in entering the energy sector, and the government revised its policies in 2002, to further encourage investment in power generation. The government, however, kept the same dollar-denominated incentive structure, with only mild adjustments to the policy.

However, the dollar-denominated incentives were not the biggest problem this time around. The bigger problem was the fact that the government was sleepwalking on its energy strategy, putting in place contracts and arrangements that they were not designed for.

In the 1990s, the government was looking to build peaker power plants, which are best set up as oil-fired power plants. By the early 2000s, however, Pakistan’s energy needs had grown rapidly and – following the Musharraf Administration’s failure to push through the construction of the Kalabagh Dam – the nation’s hydroelectric power generation capacity was not able to keep pace.

The government decided to incentivise the private sector to step in to provide more of the base load of electricity generation, which in itself is not a bad strategy. However, the Musharraf Administration failed to realise that while oil-fired power plants were appropriate for the peaker plants built in the 1990s, building more oil-fired power plants to handle the base load was a downright foolish idea, especially when the government was so keen on giving away natural gas to just about anyone who asked for it.

Oil is an expensive fuel, one that Pakistan imports, and one that has very volatile, US-dollar denominated prices. Yet under the 2002 IPP policy, the government allowed the construction of nearly 3,000 megawatts of power generation capacity, and most of that was oil-fired. In addition, the government also started using the older oil-fired power plant fleet built in the 1990s as part of the base-load as well.

At its peak, over 36% of Pakistan’s electricity generation came from oil-fired power plants. That made the country severely vulnerable to an oil price shock or a collapse in the price of the Pakistan rupee against the US dollar. Lucky for Pakistan, both of those crises decided to hit the country one after the other in 2008.

The predictable disaster struck: the cost of generating electricity rose sharply, but the government – in a populist bid to try to win the 2008 election – decided not to pass on the full costs to consumers, and instead absorbed it in the form of a partially informal subsidy. And thus was born that bane of the energy sector’s existence: circular debt.

The origins and nature of circular debt

Circular debt is a complicated beast, made more complicated by the fact that while it was dramatically exacerbated by the rise in the cost of power generation owing to fuel price increases, its origins are actually in electricity theft, and the government’s feeble attempts to curb that theft.

Electricity theft in Pakistan has existed for decades, to the point where there is now a whole sophisticated moral philosophy that surrounds the practice. And in its own way, the government has always tried to crack down on it by not allowing the electricity companies to pass on the full cost of the theft to paying customers. They can pass on part of the cost, but not all of it. The idea behind this policy is that it is meant to incentivise the electricity distribution companies to crack down on electricity theft. (This policy is dumber than it sounds, as we will explain below.)

When the cost of generating electricity rose dramatically, and the government’s ability to keep up with the subsidies needed to avoid passing on the full cost to consumers could not keep pace with that rise, the real problem arose. The policy of not allowing the full pass-through of the cost of theft onto paying customers always created a cash flow constraint on power distribution companies. But add in the delays in subsidy payments, and that constraint became a full-blown chokehold.

You see, if an electricity distribution company cannot collect the full cost of power generation from its paying customers because it has a lot of thieves and the cost has generally gone up, it cannot afford to pay the power transmission companies, which in turn cannot pay the power generation companies. Those power generation companies cannot pay for the fuel from the oil marketing companies, and the oil marketing companies then cannot pay the refineries, and the refineries then cannot pay the oil and gas production companies.

This cascading effect is what we call circular debt. It is circular because the government owns large parts of the energy supply chain, and its inability to pay subsidies on time results in the companies it owns not being able to pay it the dividends they would normally pay, which constrains the government’s cash flows further. The government is effectively choking itself through circular debt.

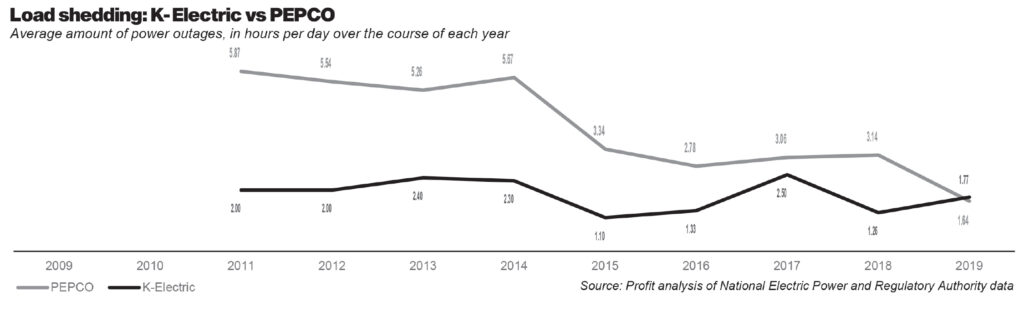

And of course, it also chokes the power sector because companies that cannot afford to buy fuel ultimately run out of it, and thus have to shut down their power plants, which in turn causes massive load shedding. This problem got particularly worse after 2008, when – even according to relatively ‘optimistic’ estimates from NEPRA – many parts of the country saw upwards of 10 hours a day on average of power outages.

Solving the wrong problem- Again

That bout of load shedding between 2008 and 2014 – which was particularly bad in Punjab – convinced the leadership of the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) that the best way to end load shedding was to end circular debt, and the best way to end circular debt was to reduce the cost of power generation.

This approach sounds reasonable, but it is completely wrong for one very simple reason: circular debt exists because the government does not allow electricity distribution companies – all but one of which are government owned – to bill consumers the full cost of delivering a unit of electricity to them. Allow these companies to bill the full cost, and circular debt goes away. And if circular debt goes away, so does load shedding.

So why does the government not do that? Why does it not allow power distribution companies – most of which it owns – to simply take theft as the cost of doing business in Pakistan and charge paying customers for the full cost?

For two reasons: The first is that the government is against the idea of making paying customers pay for thieves. And secondly, the government is convinced that if it raises electricity prices, the incidence of theft will increase.

The first reason is a statement of philosophy that can be proven to be misguided: the government already allows power companies to charge about two-thirds (on average) of the cost of theft to paying customers. Why not simply load the other one-third of the cost of theft and be done with it?

Well, the government argues: if we raise the prices, theft will go up. That is an empirical statement that is verifiably false.

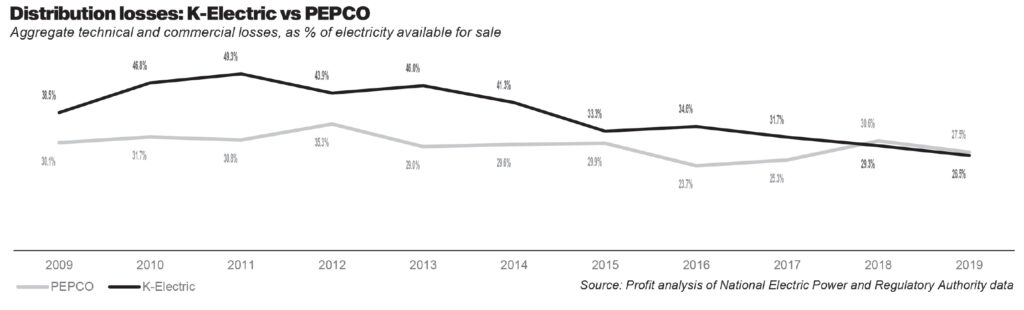

Between 2009 and 2019, the privately owned K-Electric raised prices by an average of 10% per year, compared to just 8% by the state-owned power distribution companies. Yet aggregate technical and commercial losses – an industry term that in Pakistan refers mostly to theft, but also to some losses that occur due to the physical properties of electricity – actually declined at K-Electric, going from a high of 49.3% in 2011 to 26.5% in 2019. At the state-owned companies, that number has stayed largely stagnant, declining slightly from 30% in 2009 to 27.5% in 2019.

In other words, raising prices faster than others did not prevent K-Electric from reducing theft from nearly twice the level of the state-owned companies to somewhat lower than where the state-owned companies are currently operating at.

Meanwhile, load shedding in the K-Electric area – although somewhat worse than the best year of 2018 – is still at or lower than the best years achieved by the electricity distribution companies owned by the state-owned Pakistan Electric Power Company (PEPCO).

We went further and conducted a regression analysis using price increases as an independent variable and changes in theft rates as the dependent variable and found a very small correlation, with an R-squared value of just 0.06, indicating that the relationship between raising prices and increasing rates of theft is weak to nonexistent.

And while it is true that oil-fired power plants produced very expensive electricity, particularly when oil hit over $100 a barrel, it is also true that the weighted average cost of power generation in Pakistan would always have been lower than the amount the government is willing to allow the power companies to charge consumers if one were to subtract the cost of theft.

For example, in 2012, the government was providing a Rs2 per kWh subsidy for every unit of electricity, which it was allowing the power companies to bill at approximately Rs10 per kWh. So the total cost was coming out to Rs12 per kWh. However, of that Rs12 per kWh, the cost of theft was Rs4.16 per kWh. That means that if the government were to crack down on theft, the power companies would easily have made a very healthy profit, and indeed, the government may well have forced them to reduce prices.

The capacity payment problem

In 2013, the Nawaz Administration came in, obsessed with reducing reliance on expensive oil-fired power plants and dramatically increased incentives for coal-fired power plants, since coal is cheaper than oil to produce electricity with. However, that obsession meant that the government now has a massive fleet of oil-fired power plants that it is still legally obligated to pay capacity payments in order to keep them available for peak time use.

The Imran Khan Administration now sees those massive capacity payments for idle power plants and sprang into action to try to reduce those, which it has now done by signing MoUs that convert the dollar-based 15% return on equity guarantee to a 17% rupee-based return on equity guarantee, in addition to converting the total equity amount from dollars to rupees at Rs148 to the dollar, lower than the current market Rs169 to the dollar.

From a purely negotiating standpoint, the government got a good deal. But, of course, the problem remains the same: the real problem is coming from the theft, and not the capacity payments. As we mentioned earlier, the government’s own panel estimated that even the best deal the government could strike with all IPPs would only save about Rs1 per kWh in costs.

Yet when we add in the amount of electricity that gets stolen with the amount of electricity that gets billed, but not paid for, we get to a cost of Rs4.52 per kWh of theft. It is that Rs4.52 per kWh that is causing circular debt to continue to accumulate, which in turn is causing the load shedding.

Privatisation: the obvious solution

Of course, the best way to solve the problem is to privatise the state-owned power distribution companies. Think about it this way: why would the management of a state-owned company – who are all government employees with secure jobs – care that NEPRA is not allowing them to pass on the full cost of theft to paying customers and causing their company to be mired in circular debt and losses? If the company makes a profit, they make no additional money. They do not own any shares in the company. And if the company continues to make losses, they do not stand to get fired. So why would they bother trying to improve?

Give those same incentives to a private company, however, and the logic completely shifts. A private company that can keep the gains it makes in becoming more efficient will make all efforts it possibly can in order to achieve the desired level of efficiency. That is proven by the example of K-Electric, which went from being one of Pakistan’s worst performing distribution companies to being comparable to one of the better ones in the government’s fleet.

And while private sector companies are not immune from corrupt practices, at least the government can influence their behaviour through incentives and punishments, as opposed to its own civil servants, who are often impervious to any external influences.

While recent rains have certainly exposed flaws in K-Electric’s infrastructure, the fact remains that K-Electric is also the only power company to actively demonstrate the ability to crack down on theft, which is a direct consequence of its private ownership. Yes, K-Electric is far from perfect, and the government needs to conduct much more stringent audits of the company, but the fact remains that it is the only one solving the core problem in Pakistan’s energy sector.

If there is a demonstrably successful way to solve the biggest problem facing the economy, why bother with complex plans that will only solve minor bits of the problem? Why not – in one fell swoop – generate the government significant amounts of cash through the proceeds of privatisation transactions, and also finally resolve the theft problem?

One would have thought that a right-wing government like that of the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf would be open to the idea of private ownership of assets. Yet, Pakistan’s political spectrum continues to surprise.

Brilliant article, well done Farooq.

Brilliant piece. Other daily papers don’t really measure up to this level of writing.

Great article Farooq

So final recommendation is that since the golden goose is sick so we should just kill it and grab all the eggs inside ….