Bank CEOs in Pakistan have at least one common quality: they are quite adept at dodging tough questions – seamlessly, with a poker face that would put a con man’s considerable skills to shame.

Ask them about their conservative lending approach to the private sector, and they’ll blame the counterpart’s lack of ‘borrowing capacity’. Question their abiding love for riskless government securities, and they’ll point out their lack of alternative avenues to deploy liquidity. Quiz them about their fat salaries, and they’ll draw your attention to high remuneration that their global peers receive.

They’re blame shifters. They’re question dodgers. They can’t be put on the spot – making it well nigh impossible for a journalist to pin them down.

So, it took an insider, a former head of a commercial bank – a fellow golf-playing one to boot – to get a straight, honest answer from the heads of three large banks about their readiness to meet the challenges of digital banking.

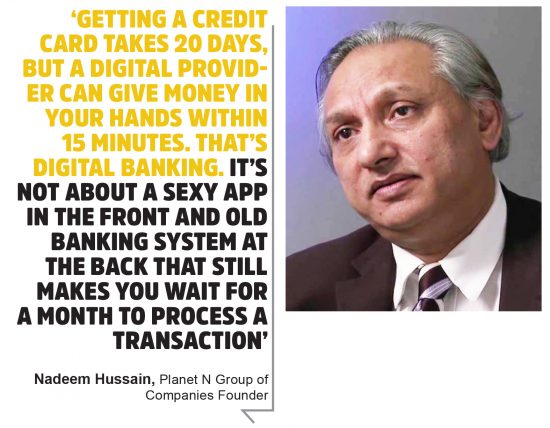

Moderating a panel discussion at the second Digital Banking and Mobile Payments Summit held in the last week of March in Karachi, Planet N Group of Companies Founder Nadeem Hussain asked the bank CEOs a blunt question: How do their respective boards of directors assess CEO performance on the digital banking front?

Their unanimous answer was that the boards simply don’t.

You read it right. The bank CEO’s compensation and bonuses are not in any way linked with his or her driving growth in the digital segment!

And, why should they bother if they can make billions of rupees every quarter just by trading in government securities?

In the same old mode

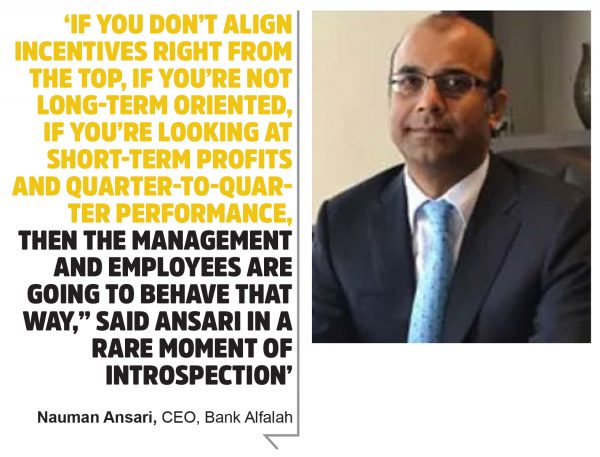

According to Bank Alfalah CEO Nauman Ansari, the only key performance indicators of an average bank CEO are returns on assets and equity, revenue, net profit, balance sheet growth etc.

“If you don’t align incentives right from the top, if you’re not long-term oriented, if you’re looking at short-term profits and quarter-to-quarter performance, then the management and employees are going to behave that way,” said Ansari in a rare moment of introspection.

“Banks are structured in such a way… structures from 30-40 years ago are still prevalent in the banking sector. When you combine these two things, innovation is not something that you expect,” Ansari said.

Banks are heavily dependent on the old way of doing business, which is mainly about catering to the funding needs of the government and big businesses by mobilising deposits from ordinary folks.

Lending to low-income people based on their credit-worthiness determined by, say, their mobile phone data does not interest commercial banks at all.

However, segments like nano-payments – tiny credit that ordinary people require on a daily basis for trivial services, like buying groceries or paying the plumber – have become an area of focus for fintechs, financial technology firms that are redefining the financial services industry.

Sea change in a decade

Speaking on the occasion, Faysal Bank CEO Yousaf Hussain said resistance exists within commercial banks to adapt to the digital age. “Priorities become very different when you see easy revenues. Banking is going to change in five to 10 years. It’s no longer going to be traditional,” he said.

He called it a challenge to convince boards to invest in the future i.e. digital banking. “To me, it’s a survival game. At this point in time, most of the boards are probably not allocating too much for this (digital) initiative. But they’ll have to do it,” he said.

Meezan Bank Deputy CEO Ariful Islam called for teaming up with fintechs to create innovative banking solutions.

“By partnering with fintechs, we can take the burden of innovation away from our organisation because it’s very, very difficult to foster a culture of innovation within commercial banks… There’s an inherent culture that banks grew up with where you don’t want to take risks,” he said.

Hussain asked him how much time a bank CEO spends on average to devise and implement digital strategies. “We don’t measure it, okay? We should. There should be metrics,” said Islam.

Within the next few years, Pakistan’s financial services industry is expected to witness a David-and-Goliath contest of sorts. Fintechs with negligible capital are going to take on commercial banks with billions, even trillions, in assets – and beat them, too.

The process has already begun. The country recently witnessed the largest transaction taking place in fintech. A small microfinance bank that Nadeem Hussain set up 13 years ago has recently been valued at $410 million.

Ant Financial, which is the world’s largest financial services company in terms of the number of customers, has invested $185 million in Telenor Microfinance Bank, previously known as Tameer Microfinance Bank. The foreign company is owned by the famed Jack Ma of Alibaba Group.

The fact that one of the most astute global investors has put in $185 million for a 45 per cent stake in a small Pakistani banking entity with a payment platform called Easypaisa should concern big commercial banks. These Goliaths are sitting on piles of liquidity and own a brick-and-mortar network across the country. Yet they seem completely oblivious to the demands of the emerging financial services industry in the new economy.

“You have to figure out from where that valuation (of $410 million) is coming from, given that the pre-tax profitability of the bank is less than $10 million,” said Hussain who founded, built and sold the microfinance bank to Telenor Group in 2016.

“My prediction is that there’ll be another big transaction in the next 12 months (of) about $200 million in this arena by another investor,” he said, adding that this is the best time to invest in the digital banking and payments segment.

Major developments in the offing

With Alibaba’s entry in Pakistan, Hussain expects three major developments to take place in the next six to seven years.

The first one is about lending customers. There’re just seven million borrowers in Pakistan. It doesn’t mean people don’t borrow. They do. But mostly through informal sources, like family, employer or local grocery store. Hussain expects the number of lending customers to surge to 50 million by 2025.

That’ll be possible on the back of data that’s going to be generated from existing railroads and will be a result of digital lending, not consumer lending. Consumer lending in Pakistan has traditionally revolved around factors like one’s monthly income and tangible assets. But digital lending in the future will be based on the use of mobile wallet and data that exists on one’s phone. “We’re talking about this explosion of digital lenders,” he said.

Companies that are best-positioned to take advantage of the emerging trends in digital banking and online payments are mobile network operators. They have a customer base of more than 100 million people along with 27 million mobile wallets. Jazz and Telenor are entering the nano-credit segment: up to Rs10,000 lent for a month to low-income people on the basis of their phone use data, not any tangible collateral.

A smartphone has 12,000 data points – a minefield for independent fintechs that remain telco-agnostic, i.e. they can work with any mobile network operator to help them harness phone data for an accurate assessment of the credit-worthiness of customers.

“Getting a credit card takes 20 days, but a digital provider can give money in your hands within 15 minutes. That’s digital banking. It’s not about a sexy app in the front and old banking system at the back that still makes you wait for a month to process a transaction,” Hussain said in a reference to the half-hearted efforts by commercial banks to come up with a customary app.

Drivers of the digital world

As opposed to the slow-moving animal that a commercial bank is, a fintech-run app looks at your payment history, makes a decision in just 90 seconds, sees whether you have an existing mobile account, connects to it in real time if you do, sends your money into it, and you can take it out through one of the 80,000 branchless banking agents across the country.

“This is happening already. Branch network (of commercial banks) has become irrelevant. That’s because fintechs use railroads that are independent of the banking system,” he said.

The second major development that Hussain anticipates is a rapid rise in the number of merchants – ones with point-of-sale (POS) machines, where cash-in, cash-out takes place for branchless banking or ecommerce merchants – from 80,000 to 10 million by 2025.

“You no longer need a POS machine because of the advent of QR code and proximity payments. Ecommerce is going to grow with the payment mechanism becoming faster. This has already happened in China successfully. This is what Ant Financial is going to do here. This is what other players need to look acct: use data to create a lending strategy,” he said.

The third development that he foresees is that Pakistan is going to have half a million data scientists by 2025 from only 50 such professionals right now. “We have invested heavily in this… Deep learning, artificial intelligence, machine learning are going to drive the digital world,” he said.

As an example, he cited a recent case where one of his companies worked with commercial banks to create a default prediction. If you are a consumer bank and you want to increase your business, his company can create an algorithm with 89-90 per cent accuracy whether your customer is going to default. Such intelligence already exists with us, he said. “The railroad that you need for digital banking to take place exists in Pakistan.”

Pakistan is going to have 3G/4G coverage of 90 per cent with close to 100 million smartphones by 2025. It’s a field wide open. Commercial banks have far more financial muscle than is needed to connect the dots, using the existing railroads and harnessing the data with artificial intelligence.

That said, given the milieu one would not be surprised, if the Goliaths of today’s banking industry end up as dinosaurs of tomorrow.