Rumours in financial markets are finicky things. In school, we were taught to ignore them, and certainly not to engage with them. In the markets, while it is probably a good idea not be a rumour-monger, it is not really possible to ignore rumours. Particularly when they are warning you about an earthquake coming your way. An earthquake that will shake up the Pakistani economy and change the way Pakistanis buy and sell things forever.

By now, anyone who has been paying attention realizes that Alibaba’s interest in Pakistan is a lot more than a passing fancy. Jack Ma clearly has plans that include dominance in Pakistan. What is also clear to people who have been keeping their eye out for the signs, and have been hearing the rumours, is that Alibaba will not be alone in its leap into Pakistan. It will likely be joined in battle by its biggest rival in China, Tencent, better known outside China as the company that invented and owns WeChat.

Sources in Pakistan’s tech industry say that they have been hearing a persistent rumour for the past several months: that Tencent is looking to enter the Pakistani market by acquisition, and that their target for doing so is likely to be JazzCash, the mobile wallet service owned by Jazz, the telecom giant formerly known as Mobilink.

This transaction, should it go through, would have a transformative impact on Pakistan’s technology, financial services, retail, and real estate sectors. It will introduce into Pakistan a fierce commercial and technological rivalry from China that will push the country’s economy forward, though it is not yet clear the extent to which its impact on local companies will be positive.

But first, a few notes for people who have not been paying attention.

How Alibaba came to Pakistan

We will skip the usual history lecture on how Pakistan’s e-commerce market evolved because it is not much of a history. For a long time, nobody sold anything on the internet in Pakistan because we are an exceedingly low-trust society and we all listened to our risk-averse uncles who said, “nobody buys anything on the internet in Pakistan”.

Then a few brave souls decided to try anyway. There was HomeShopping.pk and Liberty Books and then a few others jumped into the fray. But the market was virtually nonexistent until Germany’s Rocket Internet jumped into the fray and launched Daraz.pk.

Rocket Internet is a company whose business model is relatively simple: take the best ideas of internet companies in the United States and Europe and try to recreate them in emerging and frontier economies, eventually selling those clone businesses to the original companies in advanced economies or anyone else who might be willing to pay up.

Daraz.pk was Rocket Internet’s first investment in Pakistan, and it was something of a mixed bag. Commercially, there is absolutely no question that it was a smashing success. Daraz is by far Pakistan’s largest e-commerce player, with an estimated 12-15% share in Pakistan’s approximately $800 million e-commerce market. It also has the largest network of vendors and other partners.

But technologically, Daraz is a primitive platform, with virtually no advanced technology or analytics to speak of, and an interface that is only slightly more sophisticated than the kind of templates one can buy off the internet for $50. Customisation is non-existent.

Then again, given the absence of well-capitalised competition in Pakistan, Daraz did not really need a sophisticated operation to win market share. All it really needed was to offer a better customer experience than its rivals, which it did. Rocket Internet was never interested in investing into Daraz any more than it absolutely needed to in order to build an attractive enough asset to sell, and it was able to achieve that with the simplest of internet technology to attract one of the largest internet giants in the world.

Enter Alibaba.

Rumours of Alibaba’s interest in buying out Daraz had been swirling since at least the latter half of 2016 and were given a serious boost in the first quarter of 2017 when Jack Ma personally visited Pakistan and publicly stated his interest in the e-commerce space in the country. It was not hard to guess that, if Alibaba were to enter the Pakistani market by acquisition, their only logical target would be Daraz.

The transaction, however, did not close until May 2018, when Alibaba bought out Daraz for a rumoured (never confirmed) $150 million. By that time, Alibaba’s financial technology (fintech) subsidiary Ant Financial had already bought a 45% share in Telenor Microfinance Bank for $185 million in March 2018.

It was the Ant Financial transaction, more than even the Daraz acquisition, that suggested that Alibaba’s interest in Pakistan was a lot more than a passing fancy. It suggested that Alibaba is not just interested in acquiring a foothold in Pakistan’s existing market. It states, unequivocally, that Alibaba intends to grow Pakistan’s market by building out the necessary – and currently missing – infrastructure.

And if Tencent is coming to Pakistan, Alibaba had better implement whatever plans it has rather rapidly, because the competition may get heated very quickly.

COD: the bane of Pakistani e-commerce

There are no reliable numbers on just how Pakistan’s e-commerce business is or how fast it is growing, but most experts agree that it is probably larger than at least $600 million and probably not much more than $1 billion on the high end. At Profit, we split the difference and assume the market is probably closer to around $800 million in size today.

Daraz, as we stated is the largest player, with revenues exceeding $100 million, according to industry sources. The second largest is Yayvo, owned by TCS, the largest courier company in Pakistan, which has revenues of $12-15 million per year. Then there are Pakistani retailers who have their e-commerce arms, the largest of which can make as much as $10 million a year, and the smaller ones of which are at around $1-2 million a year. All in, these retailers account for approximately another $100-150 million.

Regardless of how big the market is, or how rapidly it is growing, everyone agrees that it could be bigger and growing a lot faster if only its biggest hurdle could be resolved: the fact that the business still relies heavily on cash-on-delivery (COD) as its primary payment mechanism.

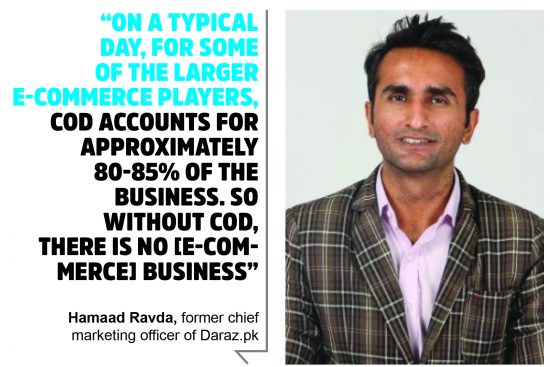

“On a typical day, for some of the larger e-commerce players, COD accounts for approximately 80-85% of the business. So without COD, there is no [e-commerce] business,” said Hamaad Ravda, the former chief marketing officer of Daraz.pk and one of the leading architects of Pakistan’s e-commerce industry. “That balance does change on days like Black Friday when you offer significant discounts, when electronic payments can go as high as 35% of all transactions.”

Ravda says that this is despite the fact that banks have made it considerably easier to make online payments through both credit and debit cards. People simply seem to prefer paying with cash.

So what is the matter with COD? In a nutshell, everything. But more specifically, four things: customer returns and cancellations are much higher, cash cycles are much longer, delivery costs are much more expensive, and the customer experience is worse.

The biggest problem with COD from the perspective of the e-commerce business is the returns: the fact that the customer is under no obligation to make the payment once the delivery person arrives at their doorstep with the goods for which the e-commerce company has already made a payment for inventory costs and delivery charges. The customer can effectively return or cancel the order on the spot.

“COD has a lot of returns and cancellations, which can account for up to 30% of all transactions. The rate for electronic transactions [where the customer pays online through a credit or debit card] is between 7% and 10%, so that differential is really, really high,” said Ravda. “As an e-commerce business anywhere in the world, if you have a 7% return rate, you’re very happy. So obviously, a higher return rate is a huge problem and it increases your cost basis.”

But Ravda points out that, on this front, Pakistan is not substantially different from India or Southeast Asia. “The story in Pakistan is not that different from what has played out in China, India, or Southeast Asia. In India, Amazon and Flipkart still do 60-65% of their business on COD even now,” he said.

The other problem with COD: unlike for electronic payments, where any adult can sign the delivery receipt acknowledging delivery, in the case of COD, the person who actually made the order has to physically be at the delivery address in order to receive the package and make the payment. Most people who have the earning power and inclination to shop online are not at home during business hours, which is when most delivery services attempt to deliver packages.

This often results in delivery services having to make repeated attempts to deliver packages to people’s homes, which in turn has two additional consequences: higher delivery costs, and worse customer experiences. And those costs differentials can be quite substantial.

“For a 1 kilogram package going from Karachi to Lahore, if I have an electronic payment, TCS will charge me Rs80 per package. For the same package on COD, I have to pay Rs250 per package,” said Ravda. “Now, if the selling price of that package is Rs6,000 or more, that difference is probably not that big a deal for me. But for things that cost less, that can be a really big deal.”

TCS and other courier services are not being malicious when they charge these differences. They are doing so because they know it is much more likely that they will need to have repeat visits before they are able to make a COD delivery than one that has an electronic payment associated with it. But of course, when a package is in transit for longer, the probability that it will get lost is also greater, which in turn leads to the problem of the customer experience being worse than for electronic payments.

“When packages get lost, the customer sometimes tries to contact the e-commerce company, and sometimes, the vendor, and sometimes the courier company, which can create confusion,” said Ravda. “But if something goes wrong and the problem is not resolved, the customer will blame the e-commerce business, not the courier company.”

And then there is the challenge of cash flows. E-commerce businesses are fundamentally supposed to be retail businesses that just happen to be based online rather than at physical locations. The attraction of the retail business is that, while your costs and inventory can be bought on credit, your revenue converts to cash instantly because the customer has to pay you before they can take possession of the goods they are buying from you. In Pakistani e-commerce, electronic transactions follow that rule, but COD transactions do not.

For COD transactions, the customer is paying before they take possession of the product, but the e-commerce business does not get paid until the courier company deposits that cash into the e-commerce company’s account, which can typically be as much as four weeks later, and sometimes even longer. For nascent startups low on cash, that can serve as a death knell. It is the reason why many e-commerce companies struggle to stay alive beyond a few months.

“Both TCS and Leopard have tried to improve their performance on this front, but it is still pretty bad,” said Ravda. “Leopards, in particular, has done a very good job in really listening to vendors. It is not easy, but easier to work with them.”

The central problem, Ravda points out, is that Pakistani courier companies are simply not designed to handle large scale COD transactions, and have been struggling to keep pace with the growth in e-commerce. The solution, at least for the larger e-commerce companies, might be to do what Flipkart does in India: hire its own riders in addition to having relationships with courier companies.

“Flipkart has over 4,000 riders across India,” says Ravda. “What that does is allow them to retain control of their supply chain in the last mile, and it gives them instant control over their own cash.”

Ultimately, however, the market can only grow sustainably once it moves away from COD and towards more electronic payments. That process, however, is much more long drawn out than any of the existing players can solve on their own.

How Alibaba and Tencent could solve the problem

Given how much of the Pakistani e-commerce market consists of COD transactions – and how much of a hurdle to growth such transactions are – it makes sense that two of the largest foreign e-commerce companies entering the Pakistani market have either already bought a payments solution or are actively considering buying one.

The goal appears to be to take the power of large and respected financial institutions such as Ant Financial, and combine them with the local vendor and distribution network of the mobile wallet companies like Easypaisa and JazzCash.

“Look, the banks only serve about 12% of the population, which means that only about 12% of the population has the ability to make payments online, if you assume that everyone who has a bank account also has a debit card,” said Ravda. “Easypaisa and JazzCash add another 9% or so of the population, which is a very substantial increase in the total addressable market.”

Ant Financial’s strategy is likely to combine the offering of its product in China – Alipay – with that of Easypaisa’s mobile wallet offerings. In essence, it would replicate what Paytm built in India: a single service that combines bank accounts at formal financial institutions with the cash-vendor-dependent mobile wallet model of Easypaisa. (Yes, since Paytm has been doing this since 2010 and Pakistan Alipay will launch in Pakistan in early 2019, Pakistan’s market is in fact about a decade behind India’s.)

“Nobody takes the mobile wallet guys – Easypaisa and JazzCash – seriously except the e-commerce companies,” said Ravda. “But the banks will be lining up aggressively to do business with Ant Financial.”

Ant Financial has announced that Alipay will be launched in Pakistan by the end of 2018 and will likely be fully functional in the country by the first half of 2019. Incidentally, in case you were wondering, yes, it is Alipay that Finance Minister Asad Umar was referring to when he referred to a “PayPal alternative” that would be launching in Pakistan in the next three to four months, during his interview with Muhamamad Malick on 92 News on September 28.

And Alipay’s move into the electronic payments business in Pakistan could be given competitive impetus if the rumours of Tencent’s interest in acquiring JazzCash are true: having its biggest rival from its home market competing with it in Pakistan is likely to spur Alipay to invest more heavily into building out its infrastructure in the country.

So how will having these two companies enter the market help the transition towards COD? It comes down to the issue of trust.

“It comes down to trust. Until the trust story is not there, customers will not want to use a debit card online. Alipay might help with that though, because even though it will be operating on the back-end, customers might feel a little more safe and secure knowing that their transactions are being handled by a large global institution like Ant Financial,” said Ravda.

Some of the pain points that might get taken away once Alipay becomes fully operational is the better integration of payment solutions directly into e-commerce websites and apps. Currently, while electronic payments are possible online in Pakistan, most transactions require a customer to leave the e-commerce company’s website onto the payment vendor’s website in order to be able to accept payments. That shift to a third-party website lasts only a few seconds, and may sound like nothing, but can be the cause of a significant portion of transactions never being completed online. When the cost of clicking away from a site is zero, customers can be surprisingly fickle about the tiniest of inconveniences.

The Alibaba effect on Daraz

Alibaba’s acquisition of Daraz is still relatively recent, but the Chinese internet giant is already beginning to have an effect on the Pakistani company. Daraz has a new app on Android and iPhones that is very similar to the Ali Express app.

But the new app is just the beginning. Over time, Alibaba has big plans for transforming Daraz from what it is today to becoming a much more sophisticated e-commerce platform. “The biggest changes will be on the technology side, since Daraz has a relatively small technology team,” said Ravda. He expects there to be significant improvements to the interface of the website, its search functionality, and the customization of its interface based on the customers’ buying history.

Importantly, however, both the app and the website will have much closer integration with Easypaisa, and eventually with Alipay.

The biggest change, however, is going to be the integration of Daraz into the wider Alibaba network of e-commerce websites.

“The model for this is Lazada, which is the Rocket Internet e-commerce company in Southeast Asia that Alibaba bought. Within a year, the entire inventory of Taobao [Alibaba’s online consumer-to-consumer marketplace in China] was made available to Lazada customers as well,” said Ravda. “To an extent, this inventory is already available through Ali Express, but this is going to be much more accessible to many more people now.”

So does that mean that Daraz will shift its focus away from selling local Pakistani goods towards more goods imported from China? Not exactly.

“One of the biggest reasons Alibaba bought Daraz was because of its local vendor network, so obviously that is something that they value,” said Ravda. “This is just an additional layer of offerings that they will use to differentiate themselves.”

Another key new feature will be better communication tools that will allow customers to communicate directly with vendors, and will allow vendors direct access to their own customers through the platform. This will be particularly helpful in removing some of the coordination irritants that can arise in the case of logistical issues relating to delivery, in addition to questions about inventory, customization, bulk ordering, etc.

And of course, Ant Financial’s superior resources will help with fraud prevention, which helps the market as a whole, as well as providing vendors with better analytics that help them understand their own customers better and in turn incorporate those insights into their design process, which would improve the quality of products available to the Pakistani consumer.

What’s next for Pakistani e-commerce?

The problem for e-commerce in Pakistan is that, aside from Daraz, no other company was willing to invest the $20 to $30 million it would take to build out a serious operation. And for that, the responsibility lies with the relatively few companies that have the cash to invest in e-commerce but choose not to. In particular, the larger retailers in Pakistan – like Gul Ahmed and Khaadi – both earn upwards of $10 million a year from e-commerce but that still accounts for less than 10% of their total revenues. It is enough for them to maintain some semblance of an infrastructure for it, but not enough for them to invest an amount that could buy them an entire new factory, even though, in many experts’ views, that investment would more than pay off in terms of future revenue growth.

“People don’t appreciate what we have in Pakistan,” said Ravda. “Logistics are pretty good in Pakistan. Almost all places are covered within 3-4 days. That’s not true in Bangladesh. Sure, payments are not great, but we’ve been able to have online since 2013.”

That raises an important question: if Tencent is going to buy JazzCash, will it also buy another e-commerce company in Pakistan to follow the same strategy as Alibaba? The next largest company – and the only major company left that is not affiliated with a retailer – is Yayvo, owned by TCS, and widely rumoured to be up for sale.

Yayvo, however, is not like Daraz. It is much smaller, for instance, and does not have quite the same level of capital commitment behind it compared to Daraz. While there have been at least some rumours about Tencent being offered the prospect of buying out Yayvo, sources inside the industry say there is no indication yet that Tencent is at all interested in acquiring Yayvo from TCS.

Got to take that sweet remittances market. There is a risk that our dependence on foreign providers will increase further as regards the development of innovative payment services. Local banks have been defensive when it comes to granting technical access to new and innovative payment service providers, which will limit the ability of external and internal Fintech companies’ ability to provide competitive solutions. These giants from China will use their network power to increase their presence further. When Amazon comes to Pakistan, I suspect they will acquire Adam Dawood’s Yayvo.

I use C.o.D only. And they often do 2 3 trips because they dont fucking call before they arrive.

I ordered from a Facebook e-commerce seller a coat. Same arrived after confirmation. But when I opened it was a landey Ka coat. And now seller is not attending my call. In my opinion pay after checking should also be must along with c.o.d in Pakistan

Tencent belongs to the same company which owns OLX. Naspers is a huge tech giant and after OLX dominating PK market, I think there will be other Naspers company entering in PK market

A desperate attempt to position Yayvo as a possible acquisition target by Tencent. Yayvo is NOT the second largest eCommerce player in Pakistan, not in terms of gmv, revenue or users.

Amazon bought Souq in UAE which is way ahead in business than Yayvo in Pakistan. Why would Amazon stoop low in PK?

As Dawood family is now on board with PTI government, no wonder their assets are getting prepped for acquisitions.

Punjab Board should Announce 9th class result

Tencent will hardly compete with Alibaba because alibaba’s name is spread widely all over the world. Tencent can beat alibaba only if it spends more money on its advertisement.

assignment bnani mjy is magazine ke 3 topics ki summary per

nice summary

peoples prefer Pakistan Post over TCS what is the reason

Comments are closed.