Design thinking. The term has been around since the late 1980s, but it has only been in the past two decades that it has become the buzzword that connects problem-solving to new age methodologies in business. To its proponents, design thinking is a cutting edge, out of the box way of approaching any problem, whether it is business, ethics, education, or socio-economic, that removes barriers and uses empathy and creativity to give unique solutions. To its detractors, it is a vague, asinine, unscientific and unsubstantiated method peddled by self-help gurus, corporate trainers, design consultancies, and academics in exchange for exorbitant fees.

Essentially, design thinking uses five steps to solve problems. The first is to empathise with and contextualise the problem so you can place yourself in it. Once you have done this, you define the problem, think of solutions without any constraints as to their feasibility, narrow down your options and begin testing your hypotheses. This non-linear problem solving technique has been used and suggested for problems within corporations, and larger issues such as changing entire structures of state education systems by creating stream lined and personalised solutions to problems.

In Pakistan, design thinking appears to have gained awareness around early 2008, the same year that IDEO, a design consultancy representing a global footprint across the globe with for profit and nonprofit organizations, invested in growing its presence through thought leadership across management magazines and conferences. While the years that followed do not suggest the concepts were applied – led by the scarcity of examples of human-centered design across industries – the approach was being taught within communications design programs at universities as early as 2009.

Dr. Suleman Shahid, an assistant professor at the School of Science and Engineering at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), has offered consultancy and training services since 2009 in the areas of design thinking and user experience (UX) design and strategy. Cut to 2020, and a short search on LinkedIn will reveal that there are nearly 9,000 professionals in Pakistan who have cited design thinking as a principle skill within their LinkedIn profiles, with the majority operating through Fiverr and the remaining split across ICT, education, telecommunications, advertising, and specialist design firms.

However, the existence of these 9,000 ‘professional’ design thinkers does not mean that Pakistan has this many people qualified as design thinkers or even this many people that know what design thinking is. It simply means nine thousand people have caught on to the buzz-term enough to put it on their CVs. The only question is, if Pakistan is using design thinking, does it just not work, or are we just not using it correctly?

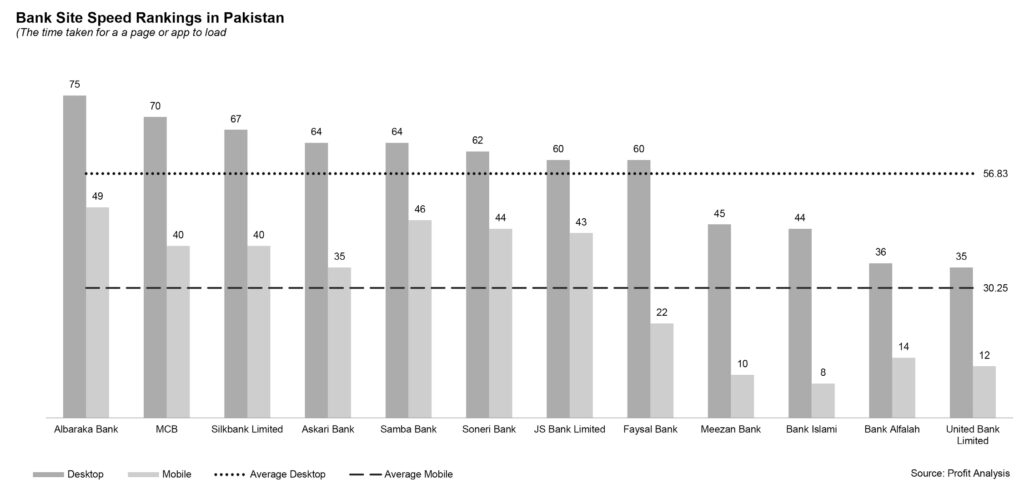

While a variety of banking organizations in Pakistan have made grand gestures in the form of design labs and visions of a technology first future, many have fallen short simply on being unwilling to invest in facilitating a rapid customer experience for the netizens. The attached chart shows how data from Google PageSpeed Insights ranks various banks in Pakistan based on how their sites are optimised for mobile and web experiences. So clearly, there is a difference between those that claim to be design thinkers and those that practice it.

Does design thinking work?

The argument that design thinkers make is simple enough. For too long our approach to problem-solving has been to treat symptoms. This is true for both small problems, like losing your keys, and for big problems like crime. According to design thinkers, we respond to these problems by fixing the symptoms, so the solution to these two problems would be searching for your keys and putting people in jail. The question that is not being asked, however, is why the keys keep getting lost and why people commit crime in the first place.

This argument of solving the root problem instead of the symptoms is the same one made by homeopathic ‘doctors’ and practitioners of Vedic medicine. It is exactly this fear of quackery that makes people skeptical about such a concept.

Tim Brown, the CEO of IDEO, is considered to be the global authority on the subject of design thinking. He is quick to point out that even though the terminology is fairly recent – with Google Trends showing the concept being searched as early as 2004 on the internet – the application of its principles can be observed in the customer-centered, systems thinking approach that Thomas Edison took to the creation of the light bulb. He considers Steve Jobs, and Ferdinand Porsche to be practitioners as well, adding that the principles were widely spread long before design was seen as a profession, the difference being that it was intuitive and its practitioners often seen as slightly odd.

“They were not typical inventors, engineers, artists or businessmen,” said Brown in a blog post. “They integrated aspects of all of these and they focused on creating solutions that met the needs of the customer. I believe that design thinking is part of a longer tradition of integrated, human centered, creative problem solving.”

The early examples were mavericks who used their intuition to determine how they approached and solved problems and created breakthrough ideas. Now we exist in a time where we need more than a few intuitive mavericks to tackle the challenges in front of us.

Survey impressions

To understand the current state of design thinking in Pakistan, Profit surveyed nearly 30 practitioners across the country on how design thinking delivers value to their organizations, how the impact is measured, the challenges believers in the framework face, and whether they feel it has worked well for their organizations.

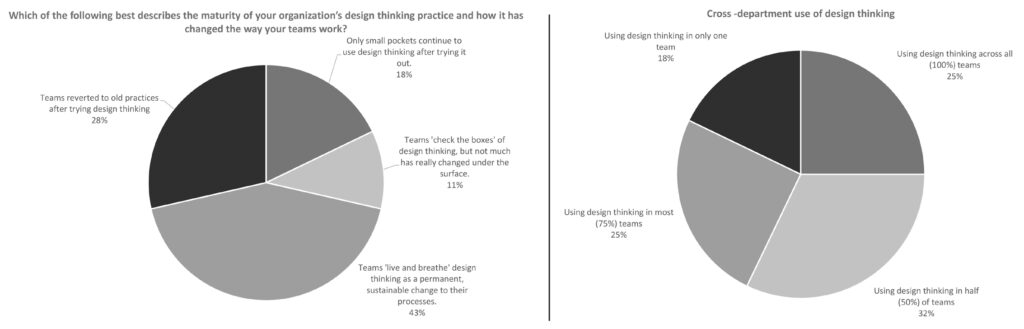

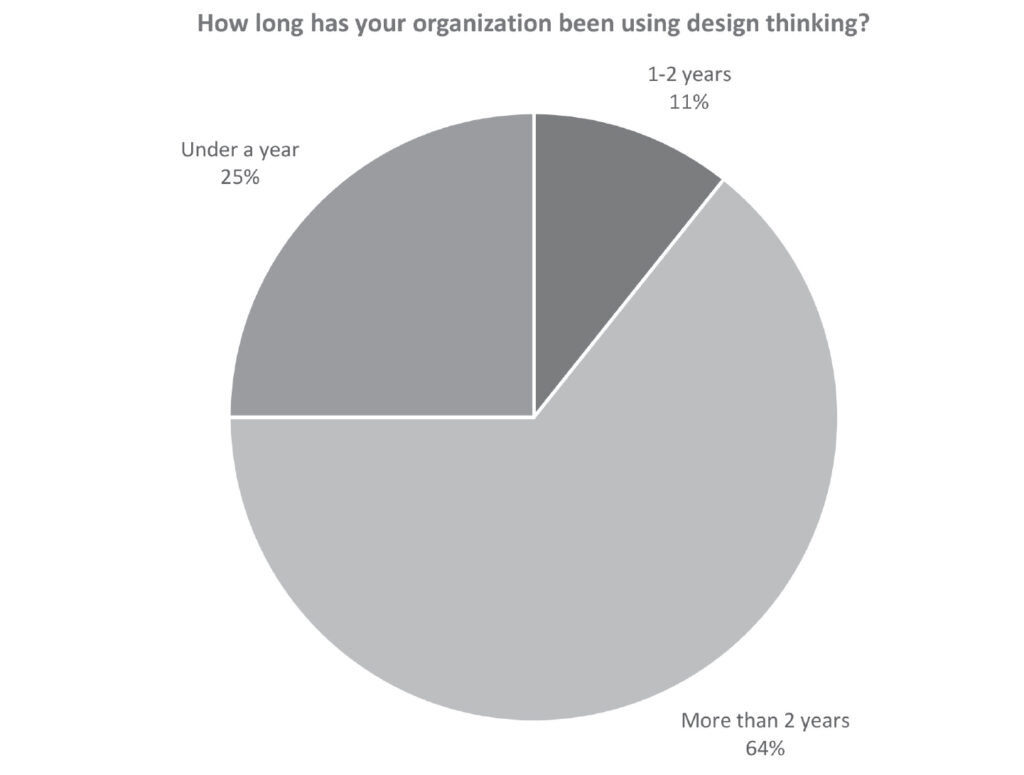

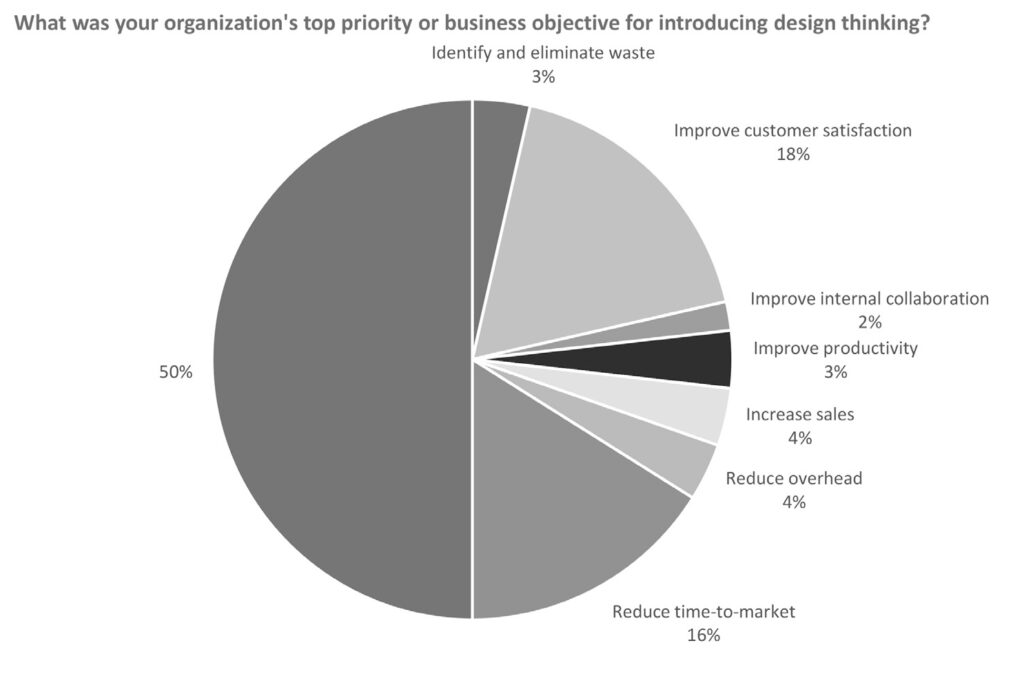

About 35% of respondents said that an organization’s top priority or business objective for introducing design thinking was to improve customer satisfaction while 32% cited the need for reducing time to market, which is often the largest problem in banking organisations that can take up to six months to roll out a product update. Nearly 65% of respondents shared that the design thinking framework has been implemented for over a year, while nearly 25% said the practice was applied throughout the entire organization instead of just one department, for which 17% respondents agreed to.

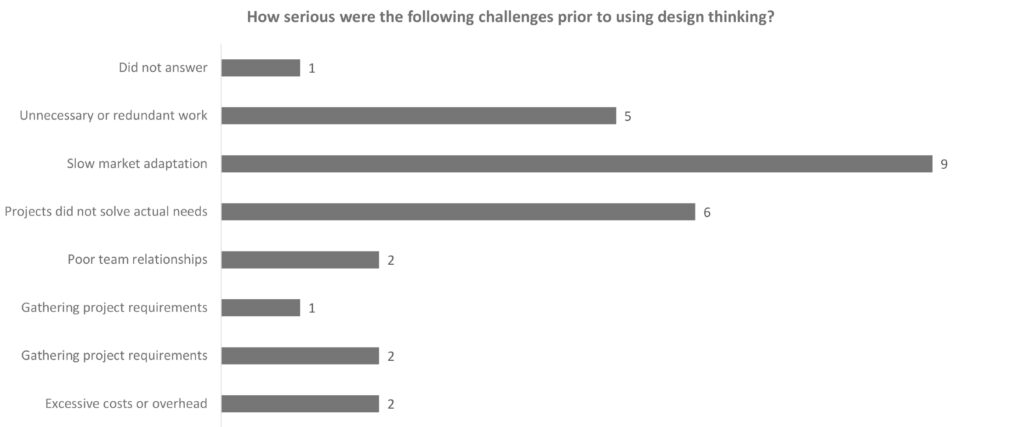

Nearly 43% of respondents said that their organisations ‘live and breathe’ design while nearly 28% said that teams reverted to old practices after trying design thinking. A third of respondents agreed that the use of the framework played a role in reducing overall project costs while 22% said that their organisations created projects that did not solve any needs prior to using design thinking.

Armed with these findings on the current state of design thinking in Pakistan based on responses from verified practitioners, Profit also spoke to several practitioners, both classically trained and those that applied the concepts in their work after coming across the framework, to understand how far the practice has come in the country and the business case for its usage.

Case study 1: Understanding the barriers of financial inclusion for women

In 2019, IDEO and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation created an initiative to promote gender-inclusive financial services in Pakistan by achieving a deep understanding of the barriers women face across access and usage.

To do this, they worked with Ideate Innovation, Karandaaz, Telenor, Jazz, and UBL to research the barriers women in Pakistan face in accessing digital financial servicesÿ specifically at the moment of cash in, cash out (CICO). Over the course of three weeks, researchers from Ideate Innovation interviewed 60 people – 45 women and 15 men – from three regions of Pakistan. To say the least, with an already massive unbanked population, prejudice against women means they have many more problems in financial inclusion than men. But how was design thinking used, or how did some people attempt to use it, to solve this problem?

Speaking to Profit, Manahil Huda, a UX Designer and Design Researcher based in Karachi explained how insights vary based on gender, and how design thinking can bridge the gap. In a previous project by the Radical Group, Huda was working with Hysab Kytab, a personal finance manager. Their goal was simple, to increase the number of female users on the app. “Preliminary research showed that the terms used were complex for housewives.” Terms like payables, receivables may even be understood by a clerk that goes out and hears them at work, but for women that stay at home and have never studied accounting, may find it confusing.

Speaking to Profit, Syed Faizan Raza, a design researcher at Ideate Innovation, made a similar observation, saying that while financial service providers can help create a better future, they require mobility, and the vast majority of women in Pakistan currently have little or no interaction with them as a result. However, digital financial service (DFS) providers – such as Jazz Cash and EasyPaisa – are uniquely positioned to come to women, rather than expecting women to seek them out.

This, of course, was the part of the design thinking equation where the design thinkers empathise in an almost Schleiermacher-esque process, by which they place themselves in the shoes of the people that are facing the problem to understand it better so that they may be able to resolve it better.

At the end of a detailed research activity, which delivered insights and archetypes to understand the root causes behind DFS hesitation and the paths of most and least resistance, researchers from Ideate Innovation presented four opportunities. The first opportunity was to launch a mobile shop rickshaw service that brings CICO services, groceries, and day-to-day products that may not be available in local markets. Additional opportunities include a female-staffed store, a bank-generated program that makes community leaders agents tasked with signing up women in the community, and an entrepreneurship curriculum delivered through YouTube.

However, Hysab Kytab could not just change the names of these categories because that would impact previously saved data. Instead, the solution devised was to add short one liner descriptions along with these jargon in order to make it easy to understand.

Another insight was that the color scheme was initially too corporate. What this means is that housewives felt the app was more suited towards people that work. That, however is not the case considering how housewives are primarily the ones that allocate expenses under a budget. In order to make the app feel more inclusive towards such a segment (and possibly students), the color scheme was changed to a more neutral scheme that was neither feminine nor masculine, and did not look as corporate and serious as it initially did. This was the innovation and ideation part of design thinking, however, there was no real information of whether the testing stage even happened.

Huda further drew a comparison between tracking your personal finance and women tracking their period. Tracking a period is not simple, there are a multitude of factors that come into play. However, women, even housewives are able to use period tracking apps on their phones with ease. That is because of how simple they are. Through the explanation of terms through jargon, Hysab Kytab became simple for women to use too.

However, that is not where this stops. Huda says, “When you enter your symptoms in a period tracking app, they often show you tips on how to manage them better. For instance, a warm glass of milk for cramps. Similarly, if someone wasn’t able to hit their savings target for a month, the team suggested the app Hysab Kytab to do the same.” As a result, the app not only tracked personal finance, it also gave tips. All these factors helped the app bring along more female users.

Case study 2: Closing the gap and solving for sensory inclusion in Pakistan

When the Family Educational Services Foundation wanted the deaf community to have hassle-free access to the Pakistan Sign Language (PSL), they hired a design consultancy to understand the root of the problem. According to Hasan Habib, founder of Designist, the project led to over 1,000 units of Raspberry Pi’s, which are mini computers, distributed across the nation, with the intervention benefiting over 60,000 people nationwide, covering nearly 100 cities and 200 schools

“The product aims to provide hearing impaired individuals the opportunity to learn and augment their sign language vocabulary to improve the quality of their conversations,” explains Habib.

While designing the product, Habib explains that his team made efforts to develop current human behavior to how sign language was being taught in classrooms and assessed the effectiveness. For this purpose, the Designist team visited several schools in Karachi, Hyderabad, and Nawabshah to observe the challenges that students and teachers faced with the language, especially the role of digitalization in this process. “We followed a Human Centered Design approach where we designed everything from the end-users perspective. Additionally the approach was co-creative where all stakeholders were involved in the design process.”

After this initial process of acquainting themselves with the problem and empathising, Habib says that they designed new ways of accessing words through easy to understand categories and search functions, which was something that users previously struggled with. Moreover, the Designist team added a function whereby users could request for words. This feature was missing from the application but was something their research showed was needed. “This project was not just to make a digital website or platform, but to enable communication and empower the deaf community nationwide.”

“It won a national P@SHA award and the international Wise award in Qatar,” said Habib. “But the most important thing is it enabled an entire community to learn to communicate, something we take for granted.”

Speaking to Profit, Habib said that because design thinking practitioners prototype and test ideas, the chances of the success of a product or service is better than they would be.

“Essentially, you are de-risking yourself. You save money by doing quick tests, rather than a large roll out,” he said. “Multiple stakeholders are brought together into the design process, which means most angles of the business and service are covered. The essence of what we do is we design based on deep research of human behavior. Our design outputs are based on what the humans’ need, not what the ‘client’ thinks they need.”

Classically trained in human centered design from Hyper Island, Habib believes that that the design thinking terminology would be better suited as being called human centered analysis, adding that his experience in the four years of operating Designist has come across multiple misinterpretations.

“The Pakistani market in terms of design is still very focused on design used for beautification,” said Habib. “It is mainly used in marketing and advertising and not necessarily as a business function to improve or create products or services. Also when it comes to design, the Pakistani market does not give it the importance it deserves. It is always treated as an afterthought and thinks it is something that can happen instantly. The market does not understand the depth required to create great design.”

Case study 3: Integrating digital products within a branchless banking service

Inspired by the design sprint methodology created by Google Ventures, Telenor Pakistan created an internal design driven innovation program called Activate, which is a five-day process for answering critical business questions. The process was recently applied to help the telecommunications giant integrate Telenor digital products inside the Telenor Microfinance Bank’s Easypaisa app.

“The key question was to create a separate dedicated Telenor branded mini store within the app, where all digital products will be placed, or have them placed individually,” said Madiha Pervez, manager of digital innovation at Telenor Pakistan. “We decided to solve this problem using the design sprint approach, where a sprint team was recruited across Telenor and Telenor Microfinance Bank. “

The team first aligned on an end goal: to increase customer acquisition for Telenor Pakistan’s digital products as well offer additional purchase use cases within the Easypaisa app, which would in turn improve in-app engagement. After identifying and interviewing five experts at the bank, researchers made inquiries which led to the understanding that a Telenor branded mini-store might not engage customers as much as placing digital products in specific genres such as gaming and entertainment.

Madiha said that the teams then had a good discussion on what questions they wanted answered and agreed on the following sprint questions, which were answered through the process in one week: Will customers buy digital products from the Easypaisa App directly or via a try & buy model? Would recharge customers want to buy digital products in the Easypaisa app? Would users be comfortable seeing the entertainment and gaming content in the Easypaisa app to buy? Would we be able to ensure seamless experience for Telenor as well as OMO customers?

The next day, her team came up with possible solutions based on existing experiences from a range of other companies as a point of inspiration. Thereafter, solution concepts were sketched, the best of which were moved to the prototype phase. A red team critiqued each solution and decisions were made within the researcher pool on which solutions would achieve the aforementioned long term goals. UX experts and designers then worked with Madiha and her team to build realistic app prototypes.

“Simultaneously, personas for interview recruitment were made,” said Madiha. “For example for our gaming products we identified male millennials within the age of 18-23 years. Real customers identified were then interviewed. We learnt by watching them react to the prototype. They were asked the sprint questions.”

Speaking to Profit, Madiha said that the majority of customers that use the app prototype preferred the try and buy option, adding that she felt a key strength of the prototype was that it enables users to personally experience the service, know the value and make an informed purchase decision. She added that the digital products were found to be engaging for Easypaisa users who were able to navigate and subscribe easily. User feedback gleamed that the app was a seamless experience to manage subscription renewal with clear visibility

“This test made the entire sprint worthwhile,” she said. “[It] reduced uncertainty around what to do next and helped us chalk out a very clear future direction.”

Case study 4: Reducing stunting in newborn children through behavior change

From December 2017 to February 2018, the USAID funded an initiative that aimed to contribute to the Sindh provincial government’s efforts towards reducing stunting of newborn children in the first 1,000 days in three districts; Ghotki, Khairpur & Naushahro Feroze. White Rice, a behavior design consultancy, was brought in to design the evaluation, train the field workers, monitor the activities, manage and analyze the data, and synthesized the findings

The goal was to address and influence a change in priorities & mindsets among mothers and caregivers which would ensure new habits such as only breastfeeding infants below six months of age, feeding a balanced diet rich in fruits to infants above six months of age, using multivitamin tablets every other day, keeping food and utensils safe from flies, and washing hands with soap before handling food and after using the toilet.

Raheel Waqar, CEO of White Rice, told Profit that the campaign began with situation analysis, followed by focusing and designing, campaign creation, campaign implementation, and campaign evaluation. He said that the primary enabler of change reported in the evaluation phase was reported to be the awareness gained from the campaign, followed by the provision of supplements, and the support received from other mothers.

“The campaign – misaali maa – reached 26,000 mothers in the three project districts,” he said. “It was rolled out for three months, from December 2017 to February 2018. Campaign activities included six planned home visits for each mother with participatory activities such as emo-demos, spot the difference, group sessions with mothers, and community sessions,” he said. “

He said that campaign activities and materials incorporated insights from the in-depth qualitative research. His team engaged participants with interactive activities instead of one-way lectures, creating key messages that addressed motivations and aspirations, while incorporating stylistic components elements of most watched media into the illustrations.

“The campaign used ‘priming theory’, which is the use of images to stimulate related thoughts, to create materials for local visibility so as to aid recall and generate conversation in the community around the campaign,” he said. “The evaluation was carried out from November 2018 to January 2019, 8 months after the end of the campaign activities.”

Participatory analysis by White Rice led to an understanding of the factors that enabled positive change while also understanding the factors that blocked positive change, with the former being the importance given to mothers and unification of mothers in the community – among several other reasons – while the latter aspects that hindered change included prevalent myths in the community, low family support, lack of access to a latrine, and low production of mother’s milk.

Qualitative research revealed that the campaign gave mothers several intrinsic benefits such as the knowledge and support – due to the campaign unifying women in the community as one – to withstand family and community pressure that perpetuates myths and unhealthy habits. The mothers surveyed felt that the campaign created respect for them in the family and in the community as an exemplary mother, which empowered them. A major benefit of the campaign was the spark of empathy in the community for the mothers’ burden and lived experiences and elicited family support for key behaviors.

Hello world