The coronavirus pandemic may be ravaging many parts of the economy, but the construction sector – boosted by recent changes in government policies meant to stimulate growth in the residential real estate sector – has seen a massive boom, with cement manufacturers reporting that they are operating at above their installed capacity as an industry.

Total cement production hit an all-time high of 5.7 million tons in the month of October 2020, according to data from the All Pakistan Cement Manufacturers Association, quoted in a research note sent by Topline Securities, an investment bank, to clients on Thursday, October 29, 2020. That is up about 15% compared to the same month last year, and up about 10% compared to September.

That number represents about 103% of the installed capacity of the cement manufacturing industry in Pakistan, which consists of 25 companies that can collectively produce about 69 million tons of cement and 66 million tons of clinker – stony material that is produced as an intermediary product in the production of Portland cement – in a given year.

“This is likely to take industry’s capacity utilization (adjusted for closed plants) to 103% in October 2020 compared to 94% in September 2020,” wrote Shankar Talreja, an equity research analyst at Topline Securities, in his note to clients last week.

Why is the cement sector doing quite so well? The government recently announced a slew of policies meant to spur growth in the housing and construction sector, which appear at last to be bearing fruit. One of those policies was the mandate by the State Bank of Pakistan for the banking sector to increase lending towards construction and real estate to equal 5% of their total private sector lending.

According to data from the State Bank of Pakistan, the banking sector’s total loan book equaled Rs8,115 billion as of the end of October 2020. That implies that, in order to meet the 5% target, banks need to increase their real estate sector lending to Rs406 billion. There are signs that, while the banking sector may still be far from meeting that goal, it is at least making some progress towards it.

“Loans to the construction sector have increased by 7.5% month-on-month to Rs336 billion (an addition of Rs23 billion) in September 2020, according to State Bank of Pakistan,” wrote Talreja.

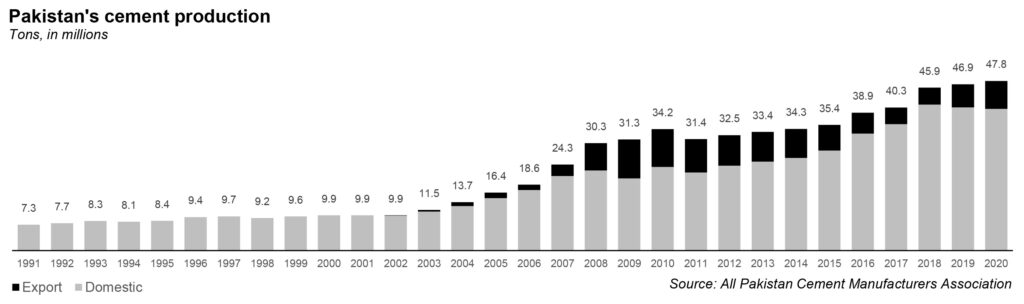

That increased domestic lending means that the bulk of the increase in cement sales has come from local sales, rather than export sales. “Local sales are likely to clock in at 4.8 million tons [in October 2020], up 15% compared to the same period last year and 18% compared to last month due to initiation of construction work on dams and injection of more liquidity in construction and housing sectors,” said Talreja.

From the ambitious Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme to the many projects of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and other construction activities, brick and mortar has been the government’s answer to uplift the economy. In fact, Prime Minister Imran Khan showed just how important he considered construction when in April this year, he announced incentives for investors and businessmen as the government tried to mitigate the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak.

In July, the Prime Minister announced major construction projects and provided a subsidy of Rs30 billion for the Naya Pakistan Housing Project so that people could build their dream house at an affordable cost.

Both of those events have caused an increase in cement prices, which in turn caused a rally in cement stocks listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. But while the rising prices have certainly helped the industry, the production data shows that the recovery has been driven in large part by actual demand for construction materials as the country’s real estate sector gears up to offer affordable housing to a rising middle class that increasingly has the ability to buy their own homes rather than continuing to live in family homes.

But it is not just rising demand that is helping cement companies. Their costs – which rose dramatically over the course of much of the previous year – appear to have topped out, creating the comfortable situation of rising demand, rising prices, and stagnating costs, which likely improve profit margins faster than even the rapid rise in revenue being experienced by the companies in the sector.

Coal prices, for instance, remain weak due to the pandemic. Besides, the sector had made some initial investments in power plants, which reduced their dependence on electricity grids – which is coming in handy right about now.

That kind of stellar unit economics – combined with demand that is slowly beginning to outstrip supply – has led at least some companies to contemplate an increase in their production capacity to capitalise on the favourable environment for the sector.

Kohat Cement, for example is investing Rs3.5 billion in its production capacity in a bid to improve operational efficiency and increase its ability to produce cement from the same assets, according to a company announcement made on Monday, October 26.

The company plans to invest Rs1,040 million in setting up a low-pressure coal-fired boiler that can generate up to 16.2 megawatts (MW) of electricity, and would help the company reduce its electricity costs. Another Rs1,260 million would be invested in setting up a cement grinding mill that would have the capacity to produce up to 300 tons per hour, which would help the company convert more of its clinker into cement.

And Rs1,200 million will be invested in setting up a grey cement production line with the capacity to produce 6,700 tons of cement per day. The company has already begun the process of scouting for industrial land to build this new expanded capacity on.

Kohat may be the first company embarking on what is likely to be the third major expansion spree the cement industry has been on over the past two decades.

The first expansion spree took place in the Musharraf Administration from 2005 through 2008, as the boom in the domestic economy – coupled with rising economic growth in the Middle East and Afghanistan – caused a surge in both domestic and export demand for cement and caused every company in the industry to invest heavily in its capacity expansion.

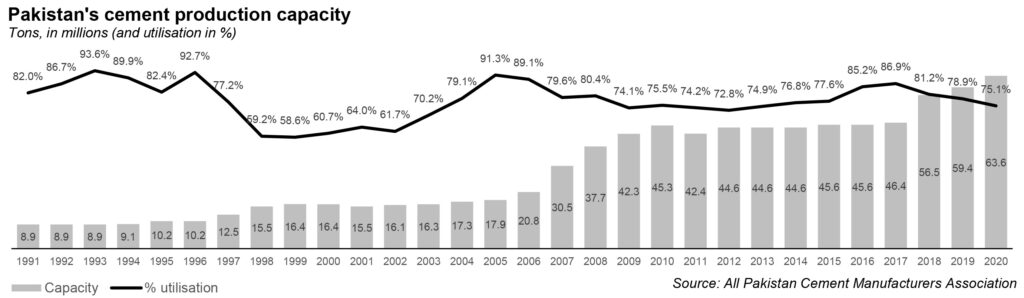

Pakistan’s cement industry tripled its capacity from just 15 million tons in 2001 to 45 million tons in 2009. Unfortunately for the industry, that expanded capacity – and the resulting debt payments – came online right after the economic crash of 2008, which resulted in a painful few years for the industry that saw anemic revenues and depressed profits as companies scrambled to repay their debts.

The second expansion drive kicked off just as Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif took office for the third time in 2013, this time in anticipation of a massive infrastructure spending increase by the government. Unfortunately for the industry, that capacity increase – more modest in scope than the Musharraf-era increase – came online in 2018, right when the Nawaz Administration lost the election.

This time around, however, the industry appears to be much more cautious about its approach to capacity expansion, with none of the major players announcing any moves yet. There are, however, risks even to being too cautious. If the country’s demand for cement continues to grow, for example, builders may need to begin importing cement, which in turn would mean that domestic cement manufacturers would start losing market share to foreign competitors in their own market.

That would be a massive risk, since market share can be hard to gain back once lost. And once the domestic market gets used to imported cement, they may not want to go back to using domestically produced cement.

In other words, the industry faces a tough choice: go on an expansion drive that will likely be expensive and result in debt and capacity coming online by the time that the boom that prompted it not being there anymore. Or doing nothing and watching their domestic market share get eaten up by foreign competitors.

excellant