If an initial public offering (IPO) is when a company first makes its shares available to the public, a delisting can be described as the reverse IPO: when it removes its shares from public exchanges and makes them explicitly unavailable to the public. That is what Unilever Pakistan did in 2013, when it delisted from the Karachi Stock Exchange, with its parent company spending $500 million to buy back its shares, an event that shook the market.

Seven years later, Unilever Pakistan remains a juggernaut in Pakistan’s food and consumer goods space, albeit one whose financial statements are no longer readily available. But what exactly did the company set out to achieve when they decided to delist from the exchange? And how successful were they in achieving it? With access to its financial statements from 2014 through 2019, Profit examines the progress Unilever Pakistan has made since its delisting.

In this story, we will cover the history of Unilever in Pakistan, its decision to delist, and the impact of that delisting on the capital markets, and finally, what it hoped to achieve from the delisting and the degree to which it was successful in achieving its stated goals.

For this story, Profit did contact Unilever Pakistan, and their spokesperson Hussain Ali Talib did send us a response, but the response included few details about the company’s strategy since the delisting. So much of our analysis relies on the financial statements themselves, and what they reveal about the company, rather than commentary from the management.

There is no doubt that Unilever is an important part of the Pakistani corporate landscape, a training ground for highly talented and qualified professionals, and what happens at the company matters to the Pakistani economy. The delisting made it more difficult, but not impossible, to understand what is happening at Unilever in Pakistan. Here is their story.

Unilever in Pakistan

If you are old enough to remember advertising from the 1990s on Pakistan Television, you may remember that the company we refer to today as Unilever was known back then as Lever Brothers. The story of that company starts in 1885, when two brothers – William and James Lever – started a soap manufacturing company, initially by buying out a small soap maker in Warrington, a small town in England.

The brothers teamed up with chemist William Hough Watson, who had invented a new process for making soap that relied on using glycerin and vegetable oils such as palm oil, rather than tallow, which had previously been the main ingredient. (This last bit – about the use of palm oil – will become relevant in the story of Unilever globally, as well as in South Asia.)

Lever Brothers went on to grow into one of the largest personal care companies in the world. After all, if you start off making soaps so that people can clean themselves by washing their hands, and while taking a bath or showering, it is a logical next step to begin producing shampoos to wash hair, and deodorant to ensure that one does not have bad body odour too shortly after having cleaned oneself.

The company merged with Dutch margarine manufacturer Unie in 1930, and changed its global name to Unilever, but never changed its Lever Brothers brand name in most countries where it had started doing business before the merger, including India and Pakistan, as well as places like the United States, where their headquarters building on Park Avenue in Manhattan is still called Lever House. The Unilever name started being used more globally in the early 2000s.

Why merge with a margarine manufacturer? Because if you are creating a global supply chain for palm oil to manufacture soap, it also makes sense to explore other end uses of palm oil. Beside soap, the biggest use of palm oil is in the manufacturing of margarine.

The history of Lever Brothers in India and Pakistan goes back to 1931, when Hindustan Vanaspati Manufacturing Company was incorporated to manufacture synthetic banaspati ghee. That same year, rather than investing in building a brand from scratch, Lever Brothers decided to purchase the rights to manufacture and sell Dada ghee in British India.

Dada agreed to sell those rights, on one condition: that the name Dada be retained. Lever Brothers, however, wanted to give the brand its own touch and decided to put the L from Lever Brothers in the middle of the name, making it Dalda. The company started manufacturing and selling the product in 1937.

But of course, it is not enough to simply start manufacturing the product. For a new category of products like banaspati ghee, consumers have to be convinced to try the product. “The challenge for Dalda in the initial years was to drive home the point that it tasted just like desi ghee, had deep-frying properties like it, but unlike ghee, it wouldn’t feel heavy either on the pocket or the palate,” said Sagar Boke, head of marketing at Bunge India (the current owners of Dalda in India) in a 2015 interview with Indian financial newspaper Business Standard.

To get around that problem, Lever Brothers began what is believed to be one of the first multimedia advertising campaigns in South Asia. “In cities, roadside stalls had men preparing tasty snacks using Dalda and offering them to the passers-by. Short films were screened in theatres. An intriguing, round-tin-shaped van roamed the streets. Attractive leaflets were handed out and small tins of banaspati sold. People were encouraged to smell, touch and taste the product. In villages, wandering storytellers were roped in to talk about Dalda. Different customers were targeted using different pack sizes – hotels and restaurants were offered large, square tins and individual consumers small, round tins,” writes Malathy Sriram, in the Indian business publication, BusinessLine.

The marketing campaign, designed by the firm Lindas, worked, and Dalda became a household name throughout South Asia, and largely remains so today.

Yes, in case you are wondering, the roadside thela-wala making bun-kebabs, samosas, and pakoras was popularised by Unilever as part of a marketing campaign to convince your great-grandmother to start buying Dalda, which you probably also thought was a product manufactured by a local company.

That is how local Unilever makes its products feel: people have forgotten that they are manufactured by a global multinational company. Even Unilever’s soap brands have a ‘local’ feel to them. How many people who buy Lifebuoy or Vim would know that these products are manufactured by a multinational rather than a local company?

(In 2003, Unilever made the strategic decision to sell of the Dalda brand in both India and Pakistan. At the time, Dalda accounted for just under 19% of Unilever Pakistan’s revenues, so the sale meant a significant reduction in the size of the company’s business in the country. In Pakistan, Dalda is now owned by the Westbury Group, a palm oil trading conglomerate owned by Karachi-based brothers Bashir Janmohammed and Rasheed Janmohammed.)

That is a very British approach to multinational management: use the core manufacturing and branding expertise to create and sell products that are popular in the local market, and only cross-sell across markets if there is broad appeal. By contrast, the American approach is epitomised by Procter & Gamble, which believes – like Americans – that everyone wants to live like an American and hence has a relatively uniform set of brands available worldwide.

(Remember that P&G versus Unilever contrast. Because it becomes relevant in the next part of the story.)

One other element of Unilever was very similar to other British companies that do business in Pakistan: a commitment to employee welfare. Unilever has been consistently recognised as one of the best employers in Pakistan, and it is not by accident.

“Unilever has been recognized as Employer of Choice for 11 years consecutively,” said Hussain Ali Talib, spokesperson for Unilever Pakistan. “We are the only FMCG with 100% of our sales force with medical and educational insurance coverage. On the diversity and inclusion front, Unilever has demonstrated thought leadership whereby we have recruited more than 25 transgender people, 100 differently abled and 3,500 widows, and are pushing the agenda further every single year.”

Paul Polman and the delisting

After decades of Unilever and P&G being two of the largest consumer goods companies that had completely differing approaches to multinational management, something extraordinary happened. In 2009, Unilever hired Paul Polman – a Dutch executive who had spent the first 27 years of his career at Procter & Gamble – to become their global CEO.

When he took over, there was a perception among analysts that perhaps Polman would bring in more P&G-style global brand management trends to Unilever, which had historically given a lot more local autonomy to its global subsidiaries than P&G. While that trend has not come to pass, Polman did initiate one change that had a major impact: he began delisting as many of Unilever’s publicly listed subsidiaries worldwide as possible.

In Pakistan, that meant delisting the main subsidiary – Unilever Pakistan, which had been publicly listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange since December 1980.

On November 27, 2012, the company announced that it would buy back the 25% of Unilever Pakistan that was not owned by the global parent. The announcement was not well-received by the market, which was especially insulted by the fact that Unilever announced that the buy-back would be at the closing price on the day of the announcement: Rs9,700 per share, which implied a valuation of the company at Rs129 billion ($1,349 million at the time), or about 23.6 times trailing 12-months’ earnings, at a time when even local consumer goods companies were trading at closer to 30 times trailing-12 months’ earnings.

There was a shareholder revolt, led by some large institutional investors based outside Pakistan. One of the most outspoken shareholders was the New York-based hedge fund Acacia Partners, which then managed about $4 billion in assets, including $75 million worth of investments in Pakistan. Acacia owned about 4.1% of Unilever Pakistan and sent strongly-worded letters to all three stock exchanges in the country.

“We believe the proposed de-listing of the company would, if approved, be a great tragedy for minority investors, the stock exchanges of Pakistan and the country overall,” wrote the fund in its letters.

Foreign investors in particular were perturbed at the prospect of losing the ability to invest in one of the fastest-growing blue-chip consumer goods companies in Pakistan.

“Food and consumer goods companies represent only about 6% of the market capitalisation of the [benchmark] KSE-100 index, far lower than the 18% or so that it is in India and Southeast Asia. If Unilever Pakistan gets delisted, that number goes down further to around 4%,” said Puneet Saraogi in an interview with The Express Tribune at the time, a director at the Singapore-headquartered Arisaig Partners, an asset management company with a 5.8% stake in Unilever Pakistan, the single largest minority shareholding.

At the time, Unilever was one of the best performing stocks in Pakistan. During calendar year 2012, the stock soared by 81.5% in calendar year 2012, vastly outperforming the benchmark KSE-100 index’s rise of 49% during that year. The stock’s rise had been largely based on its stellar financial performance. During the first three quarters of 2012, while the company’s revenues increased by 15% to Rs43.9 billion, its profits increased by a staggering 49%, on the back of improved margins.

Foreign investors wanted either no delisting, or if there was going to be a delisting, a price of between Rs20,000 and Rs25,000 a share. Unfortunately, in reality, neither Unilever nor the foreign investors were empowered to make that decision since under the Karachi Stock Exchange’s rules at the time, the KSE management was supposed to decide the price.

KSE management were the first to acknowledge that it was a bad system and said that the reason the rule existed that way was because, while the exchange had a very well-established procedure for companies that would be delisted due to defaults, it never occurred to them to create rules for voluntary delisting.

Ultimately, the KSE management proposed a Rs15,000 per share delisting price, which, on April 3, 2013, the Unilever management accepted. Foreign investors were absolutely livid, but since many of them had mandates that prohibited them from owning shares in private companies – and others simply did not want to own shares in companies where they did not know how they would be able to sell – they ended up deciding to sell.

That Rs15,000 per share price meant that Unilever Pakistan was valued at Rs200 billion ($2,038 million at the time), or about 36.4 times 2012 earnings (price to earnings ratio).

Interestingly, not all minority shareholders sold their shares. According to Unilever Pakistan’s financial statements, at the end of 2013, the company had been able to buy back nearly 3 million of the 3.3 million shares, or about 89.4% of the total shares owned by minority shareholders. Unilever’s global parent had been able to increase its shareholding in Unilever Pakistan from 75.1% at the end of 2012 to 97.4% at the end of 2013.

But that still left a stubborn 351,277 shares of the company – representing 2.6% of total shares – still in the hands of minority shareholders. Since then, the company has been making progress in buying some of those back. By the end of 2014, it had been able to decrease minority shareholding to just 1.2% and to just 0.9% by the end of 2017. But apparently there are still 1,662 very stubborn minority shareholders who have refused to sell their shares more than seven years after the delisting.

Incidentally, Unilever had not one but two separate publicly listed subsidiaries in Pakistan. The bigger one is Unilever Pakistan, which was delisted. The smaller one is Unilever Pakistan Foods Ltd, which is still publicly listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Why delist, and what happened next?

That raises the question: why spend nearly $500 million to buy back the shares of one’s own company from minority shareholders? At the time, Unilever Pakistan’s executives said that they planned on increasing their investment in Pakistan by doing so.

“The increased stake reaffirms Unilever’s strong commitment to local operations and to Pakistan’s economic potential,” said Ehsan Malik, then chairman and CEO of Unilever Pakistan, in an interview with The Express Tribune in November 2012. “Through this process, Unilever Overseas Holdings is actually increasing its investment in the country by a substantial amount.”

The management did not want to put it in blunt terms, so we will: basically, Unilever wanted to go on an expansion drive in Pakistan and wanted to make sure that it did not have to share any of the benefits of the increases in revenue and profitability with minority shareholders. In short, to the Unilever management, spending $500 million was worth not having to share 25% of all future profits with minority shareholders.

So, let us take a look at what has happened to the company’s operating performance since that delisting. The last financial statements released by the publicly listed Unilever Pakistan were for the year ending December 31, 2013. Profit has been able to obtain the six annual financial statements since that time. (We assume it is too close to the end of the calendar year 2020 for the annual financial statements for that year to be completed by now.)

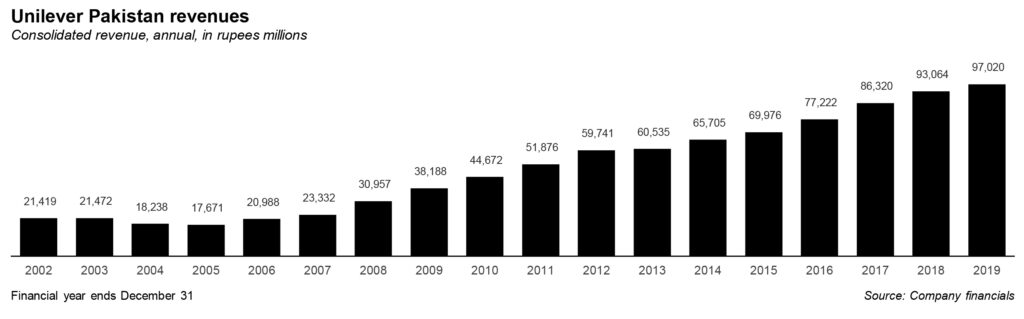

On the revenue front, the performance appears on the surface to be less than stellar. Revenue growth for the six years since the delisting has been an average of 8.2% per year. By contrast, Unilever Pakistan’s revenue grew by a staggering average of 17.2% per year in the six years immediately prior to the delisting.

Even if one takes into account the fact that inflation in the period prior to delisting was much higher than it as since the delisting, the numbers are not a flattering comparison. In the six years between 2007 and 2013, inflation averaged 12.5% per year in Pakistan, which means that Unilever Pakistan’s inflation-adjusted revenue growth averaged 4.2% per year. Between 2013 and 2019, inflation averaged just 5.4% per year, which means that Unilever Pakistan’s average inflation-adjusted revenue growth rate declined to 2.6% per year in the six years following the delisting.

So, what exactly is going on? Well, it is not an easy time for consumer goods companies in Pakistan and Unilever is simply dealing with the same consumer spending slowdown that other companies in the industry are facing. The problem is not Unilever-specific: it is an economic problem for which Unilever and its competitors are facing the consequences.

What is more revealing is the part of Unilever’s financial statements it has much more control over: how much efficiency it can drive in its operations to improve profitability, and how much it is choosing to reinvest its profits into further expansion of its business? On that front, Unilever appears to be doing very well.

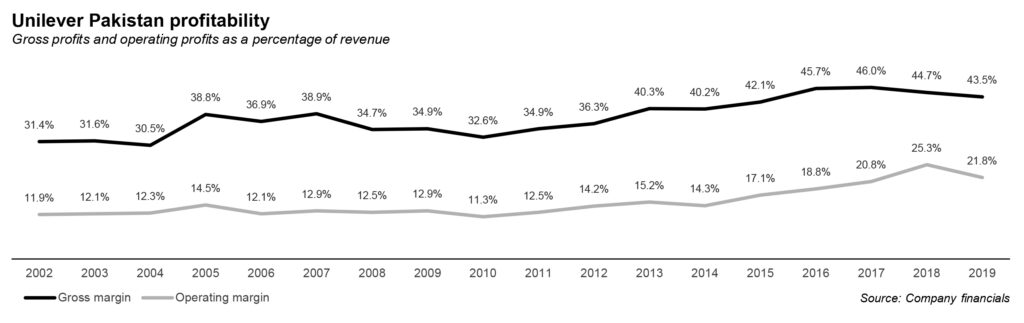

First, the profit margins: even in 2013, Unilever’s gross and operating profit margins were already the highest they had been in more than a decade at 40.3% and 15.2% respectively. Since then, however, they have only continued to increase even further. In 2019, gross margins had expanded to 43.5% and operating profit margins had expanded to 21.8% of revenue.

[Gross profit margin refers to the proportion of a company’s sales that is left after subtracting the direct cost of production for the products its sells, such as the costs of raw materials and running its factories. Operating profit is what is left after subtracting overhead costs like marketing, advertising distribution, administrative expenses like human resources, etc.]

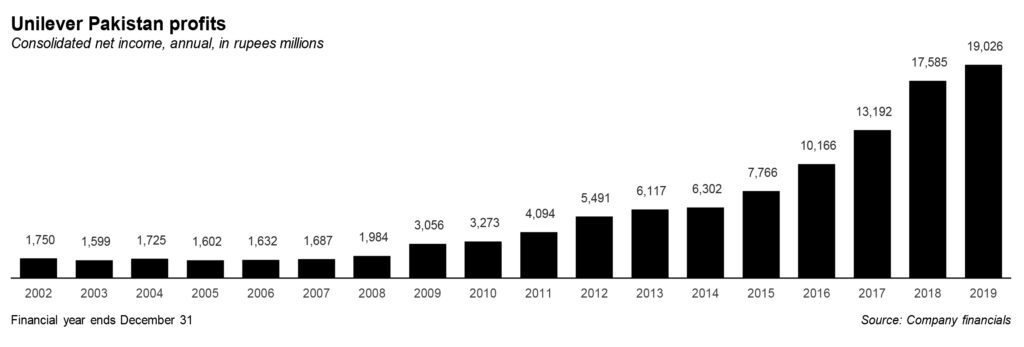

That has resulted in much faster growth in profits than in revenues. Operating profits rose by an average of 14.9% per year since the delisting, and net income by an average of 20.8% per year. While that is slower than the six-year pre-delisting average operating and net income growth of 20.5% and 23.9% per year respectively, it is significantly faster than its revenue growth. Crucially, it has been able to sustain double-digit profitability growth off a much higher baseline, which is no mean feat.

Investing heavily, post delisting

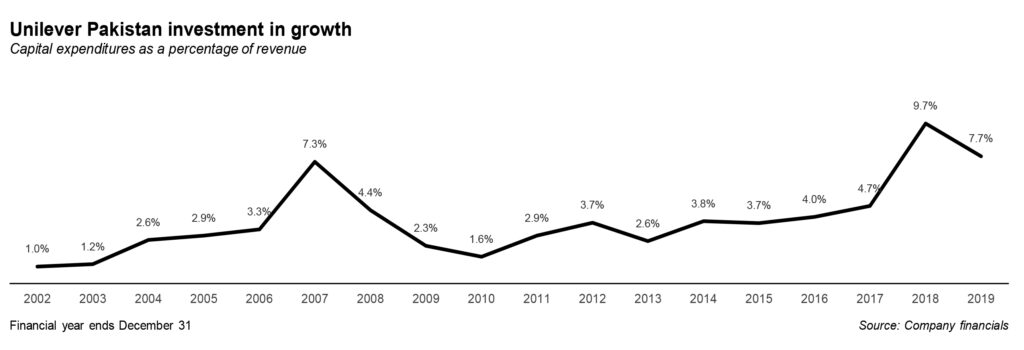

The real difference, however, shows up in the level of the company’s investments into its Pakistan operations. In the six years prior to delisting, Unilever Pakistan had invested $95 million into capital expenditure to grow its business. In the six years since then, it had invested $241 million, a massive uptick.

“In 2018, we invested a further $120 million to upgrade manufacturing operations across our four factories, and more than 98% of our products are locally manufactured,” said Talib, in an e-mail to Profit.

It is likely too early to tell just how successful the company will be as a result of its delisting from the Karachi Stock Exchange, given just how recent the bulk of its investment has been post delisting. However, there are indications that the company remains committed to being one of Pakistan’s most desirable corporate employers.

According to one Unilever employee who wished to remain anonymous, the company has constructed a fourth floor at its Karachi headquarters in the Avari Towers complex, and the floor is dedicated entirely to a large hall where the company can hold town halls, as well as an Espresso coffee shop, a Pie-in-the-Sky bakery, a Chatterbox café, and a Neelos salon.

The move is likely seeking to emulate the “fun workplace” attitude first started by Google at its offices in Mountain View, California, though the timing might be somewhat unlucky as the whole headquarters workforce is currently in work-from-home mode. Some employees grumbled that the company would have been better off giving them pay raises rather than spending on creating such spaces.

The company is also shifting gears somewhat and beefing up its ability to attract technology talent and investing in building out tech products. As Profit has previously reported, Unilever has created a direct-to-consumer platform to help consumers get instant delivery for its products. In addition, it has created a technology platform called Oscar, which will allow wholesalers and retailers to buy its products directly from the company rather than relying on major distributors.

As a result, the company’s recruiting strategy has shifted. While Unilever used to hire mostly management employees from business schools and industrial, mechanical, and industrial engineers from engineering colleges, it has recently increased its hiring of computer science graduates.

And, as always, the company loves to emphasise the fact that since it is a multinational, it opens up opportunities for employees to pursue positions abroad. “We work in collaboration with our global teams to ensure we leverage on the global scale and capability to bring the best products to our consumers in Pakistan. Unilever Pakistan has been a key talent exporter globally and many of them occupy key global positions in Unilever globally,” said Talib.

Unilever’s direct-to-consumer moves in other markets have had somewhat mixed results, so it is unclear just how successful these ventures will be for the company in Pakistan. But one thing is for certain: the delisting has clearly made Unilever Pakistan less afraid to invest and take risks. That will likely pay off well for the company – and the economy – in the long run.

Hi

I m Doctor Mukesh eye specialist

i m the biggest fan of unilever pakistan

want to become part of the unilever pakistan ?

No thanks yar

Full access nh chahye

Hum ese hi thek hain

Free me ertugral Ghazi dekh lenge

🙂

I love Unilever products

What an engaging article written in such a lucid style!