Analyses are often bound by their frameworks. One such framework often used to study the Pakistani startup ecosystem is that it’s on the same trajectory as Indonesia was a few years ago. Like any generalizations, you could find a few kernels of truth if you squint hard and massage the data enough. But for the most part, Pakistan and Indonesia are not similar enough to be useful. So, what really is the case for building and investing in startups in Pakistan?

Here’s the summary:

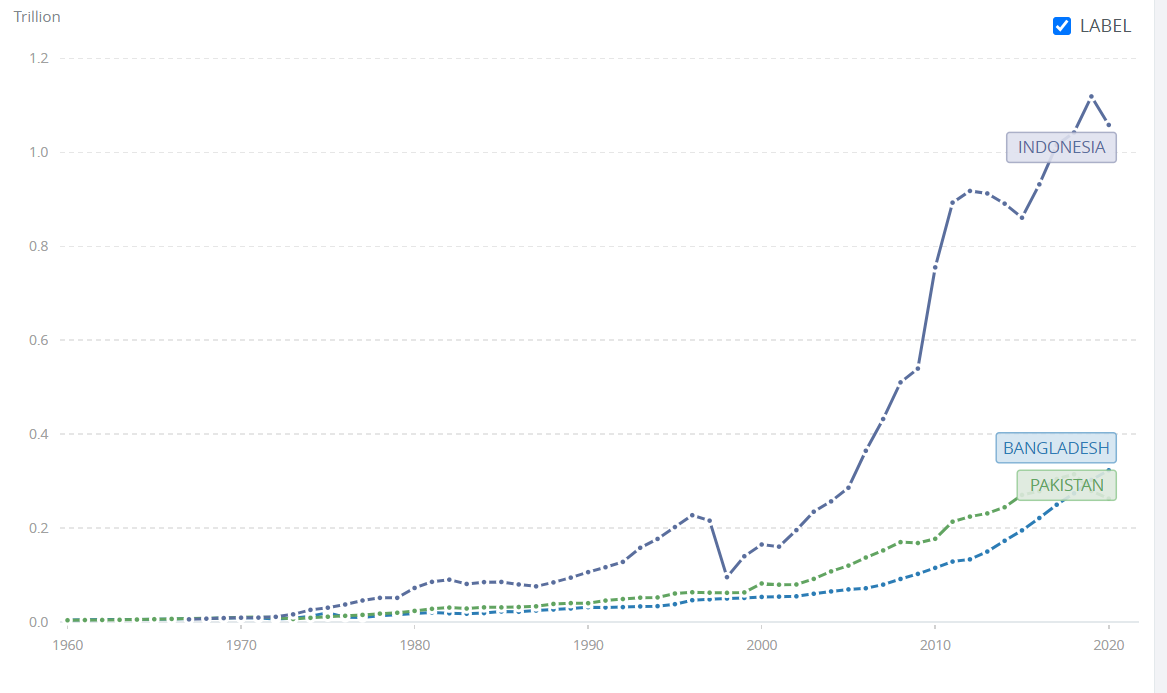

- The Pakistani market (as measured by GDP) is tiny compared to Indonesia’s. In fact, Indonesia is closer to India (0.5x), compared to the delta between Indonesia and Pakistan (0.25x). The market size is not one of the strongest reasons to invest in Pakistan — at least not yet.

- The largest opportunity in Pakistan is in fintech because banks have given up on their job. Pakistani banks are glorified treasury desks. The banking-algorithm in Pakistan is the following: get cheap deposits → lend to government → repeat. Therefore, financial penetration is abysmally low compared to any economy of comparable size.

- Invest in edges, not nodes. The natural consequence of having 220 million people is the complexity and scale required to deliver goods and services to these people. Most of the population cannot afford to pay much for any goods or services. Therefore, investment opportunities should focus on the infrastructure that underpins delivery of goods and services.

Let’s dig into each of these.

All amounts in USD unless specified otherwise.

The TAM for most businesses in Pakistan is tiny

At a macro level, Pakistan is more like Indonesia ca. 2006, and it’s not catching up soon.

Pakistan’s current GDP (not adjusted for PPP) is the same as Indonesia’s from 2006. Indonesia’s growth rate over 2006-2020 was also roughly 5%, while Pakistan’s was approximately 3.5%. The 1.5% may not sound like much, unless you know the power of compounding. In other words, Pakistan’s GDP needs to grow by 16% annually each year over the next decade to get to Indonesia’s GDP today. If anyone’s got a reasonable recipe for that one, they have my vote in the next election. But barring that, we’re not getting to that level soon.

GDP (current USD) – World Bank Data

Consumption is a major part of GDP, but it’s a function of low per capita income and macroeconomic policy

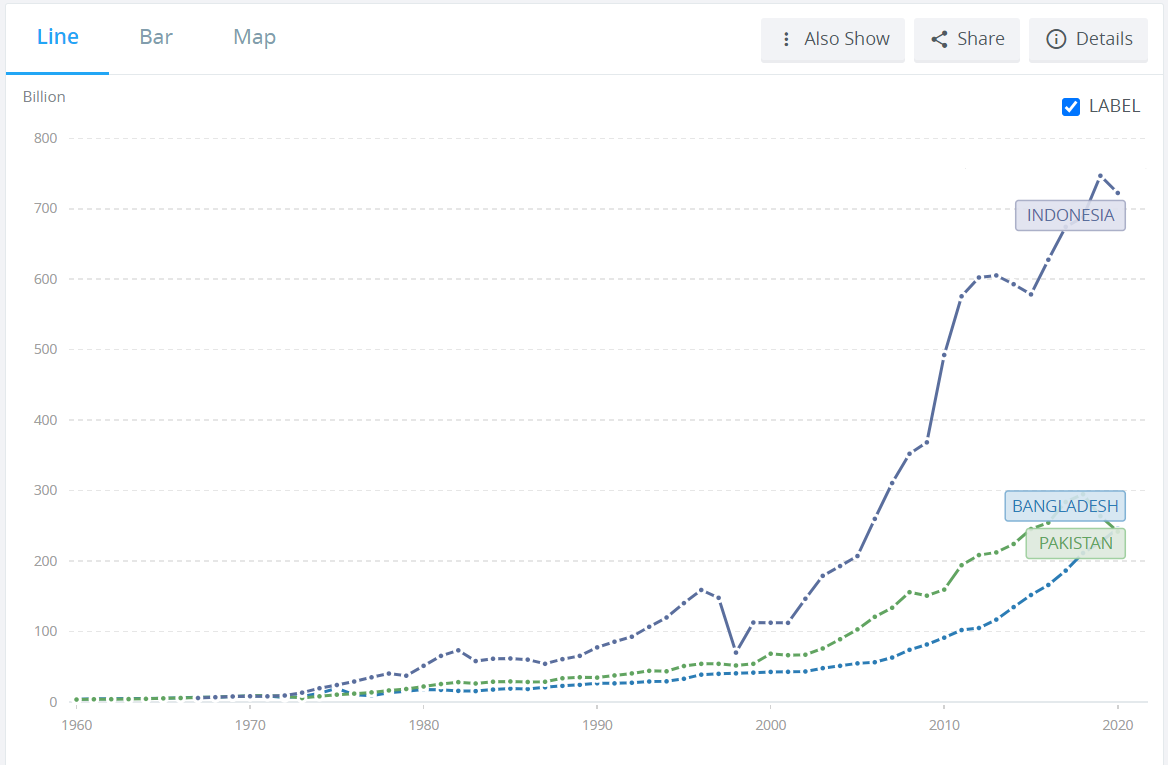

Pakistan’s consumption to GDP ratio is above 90%, compared to roughly 70% for Indonesia and 76% for Bangladesh. Yes, that implies there’s a market for consumer goods, but it’s still worth only 240 billion. Now, factor in the fact that, roughly 60% of that consumption is on food, housing and utilities, and you’re left with 96 billion of consumption on non-essentials. Apple’s revenue in 2021 was roughly 366 billion. The consumer wallet is just not that large.

Total consumption expenditure (current USD) – World Bank Data

But what about the middle class?

Pakistan has a lot of people (220 million of them apparently), and it makes sense that it would have a sizeable middle class. Who exactly is the middle class though?

Definition 1: The median income-earner.

The average monthly consumption expenditure of the third quintile of households in Pakistan was PKR 30,475, or roughly USD 170.1 By definition then, this is approximately 44 million people (or 7.3 million households) spending a total of 1.2 billion. Subtract 60% for food and rent, and we’re left with 0.5 billion of income for everything else. Annually, that scales to 6 billion. Again, not a lot.

In fact, let’s take the top quintile instead. The average monthly consumption expenditure is USD 330 per month (roughly 2x the third quintile). The same math would mean that the richest 20% consume 12 billion worth of non-essentials every year.

A very thorough analysis in the Profit estimated the size of the middle class, as defined by individuals making over USD 300 a month, as roughly 20 percent of population at its highest. Somewhere between 20-40 million people would be the most reasonable estimate.

Definition 2: Asset ownership

Another definition of the middle class may be based on asset ownership. I couldn’t find reliable statistics on vehicle or home ownership in Pakistan, but suffice to say, someone earning thirty thousand rupees a month can probably not afford a car — especially not with the state of consumer lending in Pakistan.

But just to drive home the point: vehicle sales in Indonesia were close to a million in 2019, and total car sales in Pakistan were roughly 200,000 (data from PAMA). That’s roughly a 0.25x difference on a per capita basis.

And herein lies the basic trade-off when arguing about the size of the middle-class in Pakistan: there are either not enough households or they aren’t rich enough. We can’t have it both ways.

Yes, the middle class will expand inevitable in the next decade, but we need both high and broad-based economic growth for that to happen at any meaningful pace.

Banks in Pakistan don’t do banking — and there’s the opportunity

Making money as a bank in Pakistan is easy, especially for well-trenched incumbents. You only need a treasury desk and branches to rake in cheap deposits. Everything else is garnish.

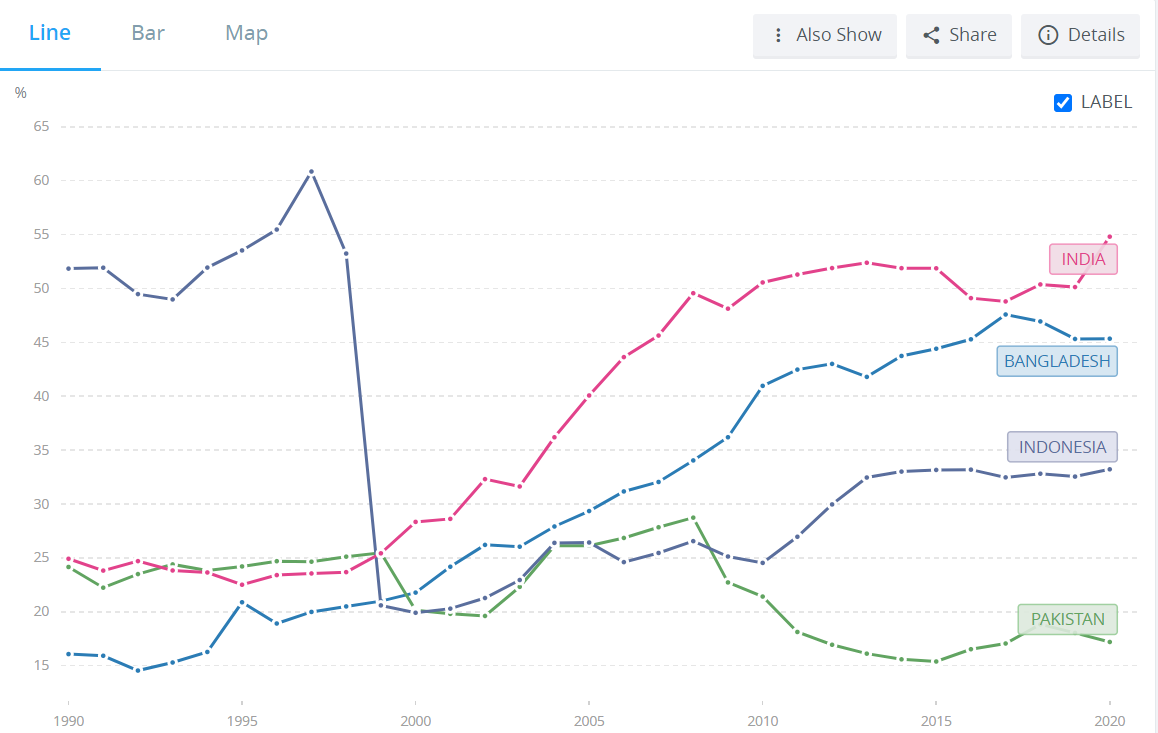

All credit-to-GDP ratios are abysmal, compared to any lower-middle or middle income country. The shape of this graph may be reproduced by any number of credit-to-GDP measures.

Monetary sector credit to private sector (% of GDP) – World Bank data

In fact, most financial sector penetration measures are dreadful. That includes:

- Deposit/savings products (# of depositors with commercial banks in Pakistan per 1000 people is 402, compared to 903 in Bangladesh)

2. Retail credit products (# of borrowers from commercial banks in Pakistan is 21 per 1000 people, compared to 83 in Bangladesh)

3. Use of payment infrastructure (value of mobile money transactions is 16% of GDP in Pakistan, compared to 20% in Bangladesh)

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that the size of the financial sector could double, even if economic growth rate goes nowhere. Fin-techs are uniquely positioned to drive this shift, since they could bring better products to a largely underbanked population. A slightly more tenuous, but still justifiable opinion, is that the underperforming financial sector is the major brake on economic growth. After all, productive domestic investment demands a functional financial system.

Invest in edges, not nodes

Something Pakistan does have going for it is its population. 220 million people are a lot of mouths to feed, a lot of hands to work, a lot of minds to educate, and so on. Unfortunately, most of them can’t afford much of anything, but the sheer number of people implies that the Pakistani economy has significantly more edges than a comparably sized economy with half the population.

Let’s run with a little model here. GDP is the sum of the economic value of transactions that happen in a given country. Each transaction occurs between two nodes (people, corporations, etc.) and occurs over edges, i.e., the infrastructure that facilitates transactions. These may be the transport infrastructure that moves goods, financial infrastructure that moves money, and so on.

The number of edges scales exponentially with nodes. In other words, trying to link 100 producers and 100 consumers is orders of magnitude easier than linking 10,000 of them with each other. That’s where technology comes in. It drives the marginal cost of setting up and transacting over a new edge towards zero.

Pakistan needs a lot of edges to provide basic goods and services to its population. That’s where the opportunity in the Pakistani startup scene lies: in logistics, fintech, marketplaces — anything that leverages the challenges that come with running a country of 220 million.

However, it’s still important to remember the first point. Pakistan simply isn’t a large market, and economic growth needs to sustain itself over a decade before the country may be comparable to Indonesia. That doesn’t mean there’s no opportunity though.

(DISCLAIMER)

I have positions in the following Pakistani companies:

Bazaar (through Alter.vc)

Maqsad (through Alter.vc)

Elphinstone

A thought provoking analysis. Every journey starts with the first step and in-case of nations, the govt has to take that step which to-date has yet to be taken. However the recent activity in the start up scene suggests that there is still hope and there are a number of companies willing to bridge the gap for the general population. At the same time, in the long run only qualified and skilled labour force will ensure consistent economic development other wise we will continue to grow our middle class by producing more babies only.

Very interesting read Faisal thanks for sharing

Hello Ozair; Thoroughly enjoyed reading your post. Is your fiction writing available for purchase? couldn’t find anything on Kindle.

As Faisal has said, qualified and skilled labour force is the key. Any insights on that? May be idea for the next article!

Ozair, this was awesome. really enjoyed reading your article here.

I love the post helpful

Really helpful post