On the 2nd of June this year, Finance Minister Miftah Ismail ordered that the process of importing edible oil from Malaysia and Indonesia be facilitated to ensure smooth supply of the commodity to the consumers and stabilise its price – which had been hiked by more than Rs 200 a day before.

He also announced that appropriate measures be taken to enhance the local production, so that the impact of edible oil imports on foreign exchange reserves could be minimised. The news was buried in the papers and went without much attention. Probably because Miftah Ismail is neither the first finance minister to give such direction nor is his government the first to think that edible oil could be produced locally from scratch saving precious dollars on the import bill.

What most might not realise is that Pakistan is dependent on Malaysia and Indonesia for its most basic caloric input. Not only are we the fourth largest importer of palm oil, we also import soybeans and other oilseeds necessary to produce edible oil and the locally essential ‘Vanaspati Ghee.

Our story begins in the 1930s – when a Dutch company called Dada in association with Lever Brothers in London (the forebearer of today’s Unilever) planned to import cheap vanaspati ghee to the Indian subcontinent.

Ghee had long been an ancient staple of the rich in the Indian subcontinent. The cooking substance made of clarified cow milk was used sparingly to make delicacies on festive occasions. Ghee, as a signifier of wealth, has even been codified into the Urdu language, with the idiom ‘paancho ungliyan ghee mein’ entrenched as a mainstream saying.

Because most Indians could not afford the product regularly, inventors in Europe had discovered a method to hydrogenate vegetable oil and turn it into a substance that convincingly mimicked the taste and function of ghee. That was the product that Dada and Lever brothers were now bringing to the Indian market.

There is a long story as to how Dada and Lever Brothers came to an agreement to launch Vanaspati Ghee under the brand name ‘Dalda’ Ghee — and you can read more about it here. But when the first tins of this product hit the market, they made an impression because of the bright green palm tree logo on yellow that they used.

The vegetable oil being used to make Vanaspati Ghee came from the seeds of the palm tree. That is a legacy that we have inherited to this day. In Pakistan, the most commonly used edible oil is Vanaspati Ghee – significantly more so than cooking oil used by most upper class families in domestic cooking. All of this comes from palm tree oil. And it isn’t just Pakistan. Since the early 20th century, the oilseeds of the palm tree along with Soybeans have dominated global demand, with countries like Indonesia and Malaysia centering a large part of their economies around the production of these oilseeds.

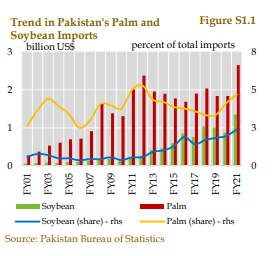

In Pakistan, nearly 90% of the import of oilseeds is constituted by palm and soybean oilseeds. In its recently released report for the first quarter of the financial year 2022, the State Bank of Pakistan included a special section on rising palm and soybean imports. According to the report, Pakistan’s palm and soybean-related imports stood at US$ 4 billion in FY21, rising by 47 percent year-on-year, compared to compound average growth of 12.3 percent in the last 20 years.

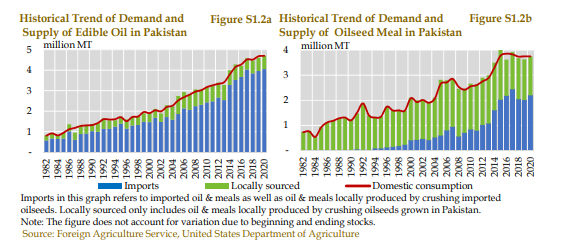

The domestic reliance on soybean and palm has been steeply increasing since the turn of the century. As a result, 86 percent of domestic edible oil consumption in 2020 came from imports up from 77 percent in 2000.

The problem, of course, is once again Pakistan’s reliance on imports. For decades, successive five year plans and other policies have tried and failed to make Pakistan self-sufficient on the oilseed front. Some of the reasons have been typical to Pakistan’s crumbling agricultural infrastructure, while others have been climactic and practical. With prices of cooking oil rising by more than Rs 200 overnight, Profit looks at the reasons behind why we are reliant on imported oilseeds and why we can’t grow them domestically and save on our import bill.

Why do oilseeds matter?

A lot of our focus in this article will be on the oil extracted from palm seeds and soybeans. That is because they are globally the most used and efficient kinds of oilseeds. Essentially, oilseeds is a term used to describe any kind of seeds or plant product that can be compressed to extract and produce oil for cooking – basically the raw product for edible oil.

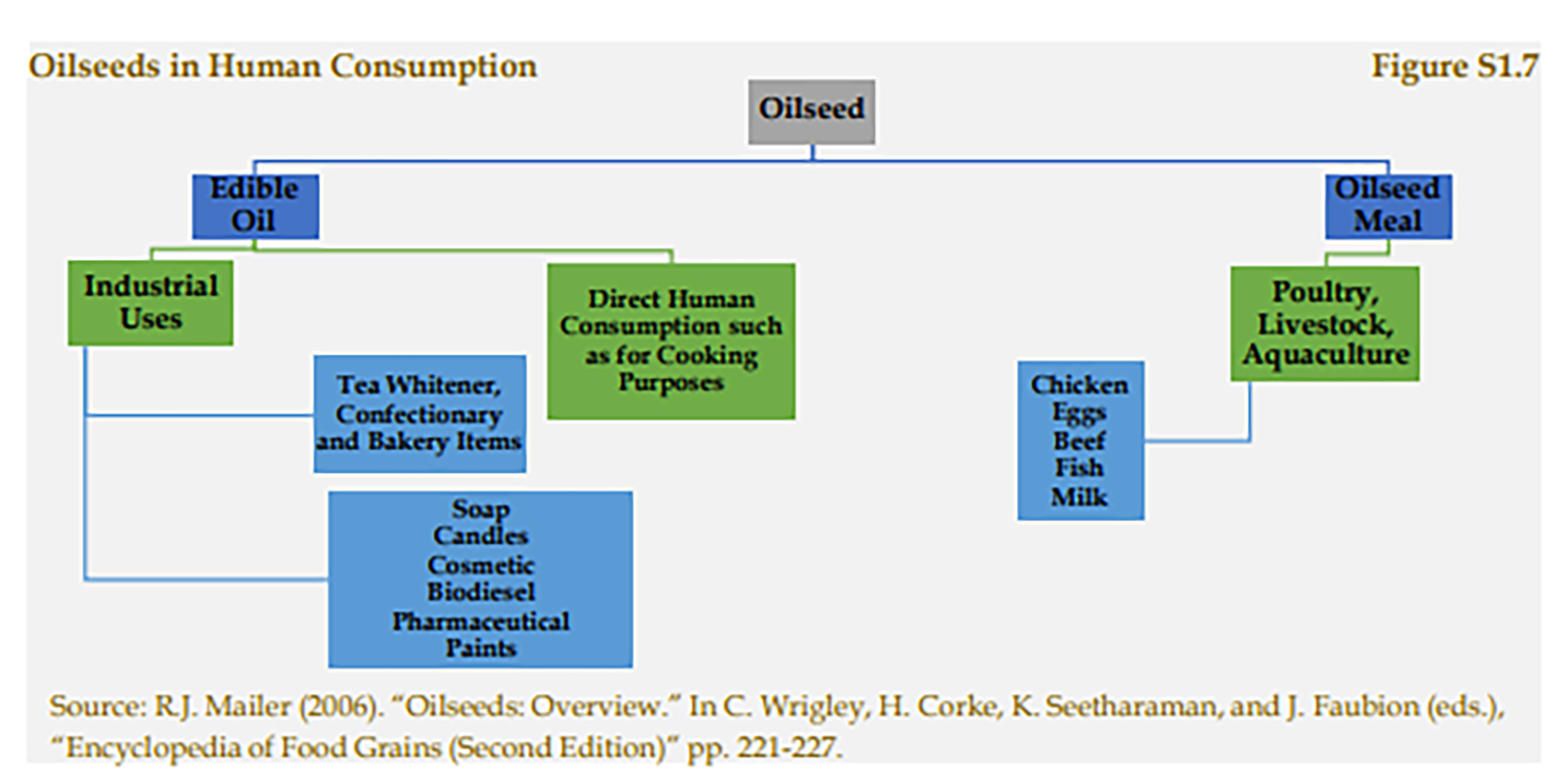

Oilseeds have two purposes. The first is to produce edible oil for cooking purposes. The other is to produce ‘meals’ using the mulch and byproducts of the compression process that are then fed to livestock including poultry and cattle.

A big part of why palm and soybean demand has risen all over the world is that it has one of the highest oil-per-hectare yields of different kinds of oilseeds, and also some of the highest protein content – which is ideal both for domestic edible oil production and livestock feed. Pakistan’s reliance on these two oilseeds is not out of global syn, and some of the largest producers of canola and sunflower – which are the third and fourth most consumed vegetable oils in the world – still rely heavily on palm and soybean.

It is natural too. The human population has grown exponentially since the 20th century, and life expectancy has also shot up. At the same time, livestock industries such as poultry have become massive – especially since the proliferation of poultry in the 1980s in the developing world. That means we need the most efficient oilseeds that can give us the required caloric output for a massive human and livestock population.

The problem in Pakistan is that we have failed to adapt to the change and grow palm and soybeans locally, relying instead on imports – which has resulted in the whopping $4 billion import bill we currently have for oilseeds. According to the earlier mentioned SBP report, total imports of oilseeds and its products surpassed 7 million metric tons in FY21, 87 percent of which comprised palm and soybean. The SBP report also points towards this, saying “ there has been little focus on palm and soybean in Pakistan. Various five year plans since 1955 have highlighted and proposed the need to focus on soybean and other oilseeds. However, lack of consistent policy has prevented oilseed crops, particularly soybean, from taking off.”

“On the other hand, whilst initial surveys and pilots on palm began in the mid90s, palm started featuring in policy documents only after 2005. However, so far policy efforts with long-term focus have not been undertaken for oil palm plantation,” it goes on to read.

The reasons behind Pakistan’s reliance on palm and soybean imports is based on a long list of demand-side, supply-side, and local growing capability issues. There is a lot riding on oilseeds, and our failure to become self-sustainable on this front has resulted in having to import a lot of these products.

The demand-side equation

A number of industries are dependent on oilseeds. The two products extracted from oilseeds are edible oil and the residual, which is either used directly as food for livestock meal or is otherwise processed into an oilseed-based meal. Oils are the direct source of fats for human consumption, whereas meals are used as feed for poultry, ruminants and other livestock, and aquaculture, which in turn are the primary source of animal protein and other nutrients necessary in the human diet – making oilseeds a very basic building block of humanity’s caloric intake.

In addition, the oil from oilseeds is used by both food and non-food industries such as biscuits, tea whitener, soap, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, paint, fertiliser and biodiesel. This makes oilseeds vital. According to the SBP report, global consumption of oilseeds has increased manifold since the 1980s, with more than 600 million tons consumed in 2019 (Figure S1.8). Although Pakistan’s share in global oilseed consumption is a marginal 1.1 percent, it follows the same growth trend, with domestic consumption up 3.5 times over 1981. The increase is driven by a rise in demand for both edible oils and oilseed meals.

On the cooking oil end of the equation, Pakistan in particular is a country with a high-dependency, even compared to other countries with similar dietary preferences like Sri Lanka and India.

Just take a look at Dalda, one of the top brands selling cooking oil in the country. Their cooking oil is made of a blend of canola, soybean, and sunflower seed oil with no mention of palm oil. However, the use of cooking oil has mostly been seen in higher income brackets in Pakistan.

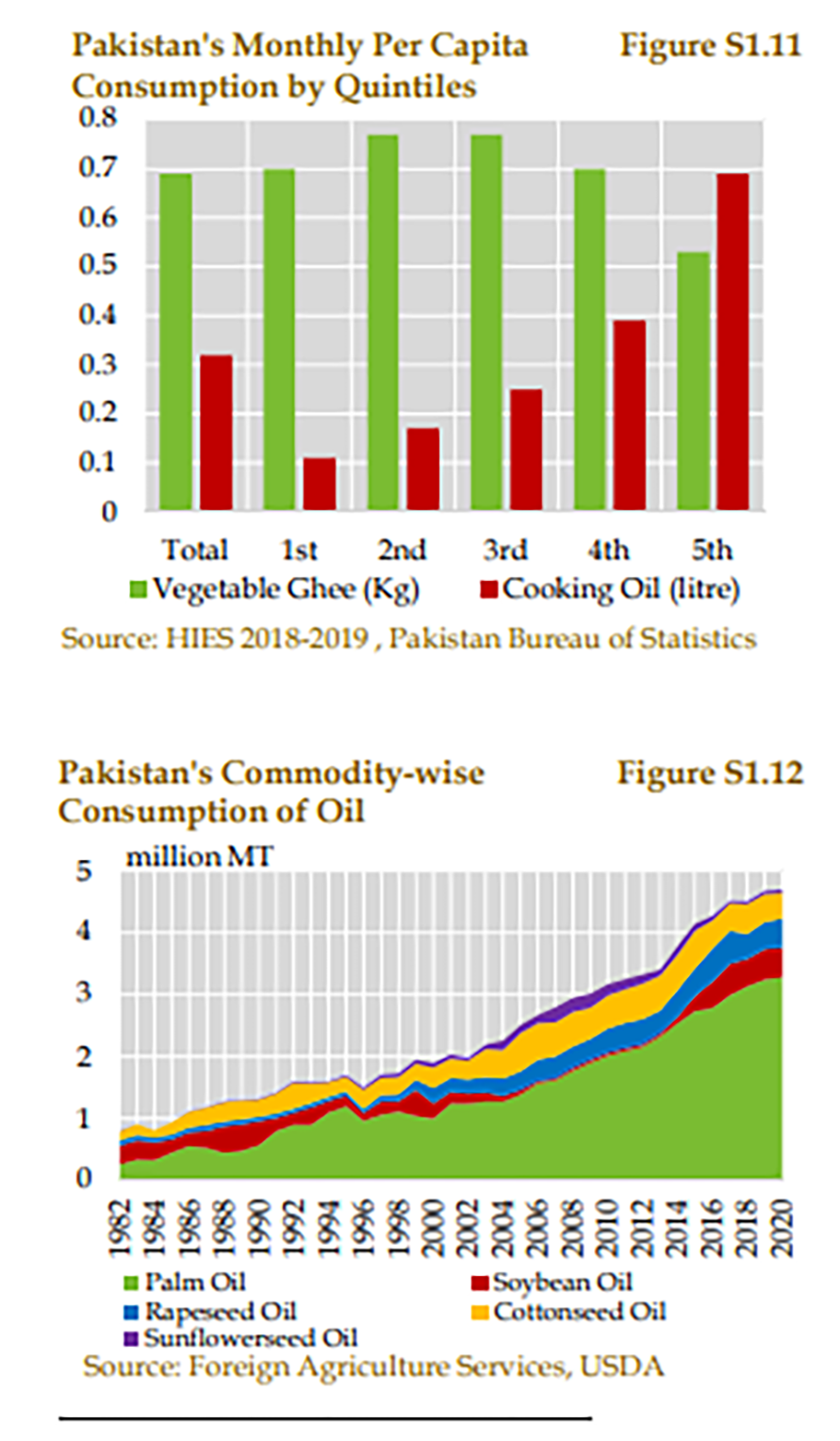

There is a clear indication that as people climb social and financial brackets, their preferences change towards lighter oils like Canola and Olive oil because of the perceived health benefits but for the most part it is palm and soybean that is doing the heavy lifting in the country. Despite consumer preferences tilting towards cooking oil in higher income groups, vegetable ghee consumption is higher than that of cooking oil at household level in Pakistan.

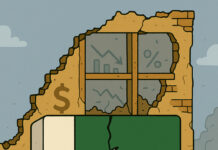

Edible oil consumption in Pakistan has increased significantly over the last few decades: from 0.7 to 4.7 million tonnes between 1981 and 2020. The main demand drivers are rising population, dietary preferences and increase in per capita income.

According to the recent SBP report: Pakistan’s per capita edible oil consumption is already higher compared to economies with similar income levels. In addition, increasing income levels may also translate in increased per capita consumption of edible oil, as will population growth. According to the UN’s World Population Prospect 2019, at constant-fertility, the country’s population in 2025 is set to reach 245 million, and 328 million by 2040. 20 This implies that demand for edible oil will continue to increase noticeably. According to estimates by Pakistan Oilseed Department, total demand for edible oil in the country is conservatively expected to grow to 5.9 million tonnes in 2025-26, from 4.7 million tons in FY21

But it is not simply edible oil that is driving this demand. Palm and soy are also preferred because of their ability to make livestock feed. In the three decades since 1990, the consumption of oilseed meals as feed for livestock has tripled in the country – a big reason for which is the growth of the poultry industry.

This is particularly true in the case of the soybean. Since it is rich in nutrition, its meals offer better digestibility, quality mix of amino acids and have the highest protein content (around 44-50 percent) compared to all other oilseed meals. These qualities make it a better feed ingredient for chicken in comparison to cottonseed – which was the traditional oilseed used in Pakistan.

According to the Pakistan Poultry Association (PPA) estimates for 2015-16, approximately 9.5 million tons of poultry feed was produced, nearly a third of which was oilseed meals. This means around 2 – 2.8 million tonnes of oilseed meals were used in Pakistan’s poultry industry. As demand for poultry increases, no of chickens raised also goes up and so does demand for soy seeds as feed.

In addition to poultry, growth in per capita beef consumption and increase in population of other livestock animals30 with a CAGR of 2.6 percent for FY02-21 period31, are also contributors to the increased demand for oilseed meal in the country

The supply-side equation

Successive governments since 1955 have been trying different approaches to make these oilseeds more easily and locally available. Cheaper and locally produced oilseeds would mean better nutrition for both humans and livestock as well as be a $4 billion relief on the import bill.

None of it seems to have worked. The National Commission on Agriculture in 1988 noted that cultivation of oilseed crops in the country had stagnated in the first four decades since 1947, in sharp contrast to the rest of the agriculture sector. The situation has not improved since then. Production of both traditional and non-traditional oilseeds crops. For instance, in 1989, the government started a 7-year National Oilseed Development Project for the promotion of oilseeds. However, the project faced bottlenecks, such as inadequate seed supply and procurement problems.

Essentially, it has been Pakistan’s weak agricultural infrastructure that has not allowed this vital crop to take hold. The fundamental reason has been the absence of a consistent oilseed policy. There is limited research on the subject, and the little that has been done has never reasonably been applied to try and see practically whether or not it works or not.

All of this is made worse because of general problems in Pakistan’s agriculture – deficiencies in marketing and procurement challenges leading to weak linkages in the value chain; and inefficient oil extraction in villages and small towns. Take simply the example of support prices – there are none for oilseeds in Pakistan despite successive governments feeling it is necessary to try and solve the issue through domestic production. It means farmers are not incentivized to grow oilseeds, and at the other end middlemen have been found to exploit oilseed farmers, such as sunflower seed producers.

Can we do it locally?

There are two parts to answer this question. The first question is whether or not local varieties of oilseeds could effectively solve our oilseed requirement. The second requires us to figure out whether or not we can grow palm and soybeans locally in enough quantities to become self-sufficient or at least quasi self-sufficient.

Can local varieties cut it:

The first problem we have with that is that our traditional oilseed varieties are not specifically bred or farmed for oilseed purposes. Take, for example, cotton seeds – which are oil seeds and have historically been used both as edible oil and to feed meals to livestock but are cultivated for their fibres more than anything else.

We grow cotton seeds for good reason – the fibres are precious. However, cottonseed is the biggest contributor to domestic production of edible oil, despite having an oil extraction rate of only 16 percent. Even on that front there has been very little good news. Cotton cultivation has been on a secular decline, the contribution of cottonseed oil to total domestic edible oil consumption has fallen to 8.7 percent in 2020 from 17.2 percent 20 years ago. Similarly, its share in meals produced from domestic oilseed crops dropped to 79 percent in 2020 from 88 percent in 2000, as per USDA data.

There are other locally produced oilseeds in Pakistan as well. Canola, groundnut, sesame, castor and linseed, are the major crops used in edible oil and oilseed meal production. Despite having higher oil extraction rates of 42 percent and meal extraction rate of 58 percent, Canola’s area under cultivation had gradually declined between 1967 and 2016. In recent years, Canola is being encouraged in Punjab through a cash subsidy package introduced in FY18,44 as a result of which acreage and production more than doubled between FY18 and FY19.45

However, despite these recent positive developments in canola, the area under cultivation of these crops is still small, and edible oil from combined domestic production of canola met only 4 percent of domestic edible oil demand in 2020, as per USDA data. Peanuts and groundnuts are even smaller acreage than canola and cotton, and on top of that are not usually used as oilseeds.

Cotton included, during the last 15 years, the local production of edible oil has registered negative average annual growth of 1.2 percent, while the demand per capita has increased by 2.3 percent, leading to increasing reliance on imports for both edible oil and meals.

While encouraging local varieties is clearly an area that needs continued attention, in the short-term it is a deadend. The next question, then, is whether or not we can grow the palm and soybean oilseeds that we have gotten used to locally.

Can we grow palm and soybean oilseeds here?

It is very clear that Pakistan’s growing imports of palm oil and soybean seeds is in line with the global consumption pattern where reliance on these two commodities has grown manifold to produce edible oil and oilseed meal purposes. However, so far policy focus on both commodities is lacking.

Attempts have been made to do this but have summarily failed. In 1994, a survey was conducted by the National Agriculture Research Council (NARC) which surveyed 3.86 million hectares in Sindh, of which most were coastal districts for feasibility to grow soybeans. The survey checked humidity, soil conditions, and existing land usage as perimeters and decided that around 1.65 million hectares were considered suitable growth in varying degrees.

However, the project faced the typical Pakistani issues. After initial years of promising growth, the pilot project faced various types of management issues and operational bottlenecks. In its assessment of the project, the SBP in its report writes “in some cases, the plantations were not maintained or were otherwise neglected; in other areas, seeds were not managed properly at pre-nursery stage. There were also incidents of inadequate fertiliser usage, inefficient water distribution, and attacks by rats. On the whole, the project was not closely monitored, partly because of institutional challenges such as those discussed in the previous section. As a result of these farm management issues, the pilot project was not successful in testing whether or not the theoretical potential was possible.”

There has been a very clear lack of will on this front. Soybeans were included in a five year plan in 1955 but did not receive a support price until as late as 1978, which was also discontinued after 1998. The crop’s progress remained weak, with highest ever production being limited to only 8,200 metric tons.

Following the increase in demand for soybean meal by the feed industry, the pace of research has recently started to pick up, where the biggest crop-specific challenge is the availability of sowing seeds suitable in Pakistan’s climatic conditions. Soybeans usually require mild climactic conditions. In light of this, a heat tolerant variety called Faisal Soybean has been developed and piloted by Oil Research Institute (ORI) Faisalabad in 2018-19. The results were encouraging in north and south but not in east and west punjab.

This implies that in the medium term, at conservative estimates of 1 tonne per acre grown at only 0.5 million acres out of total suitable areas identified, Pakistan can potentially grow 0.5 million tonnes, which is 20 percent of the country’s FY21’s soybean import quantity. However, to realise this potential, the overarching challenges to oilseed crops discussed in previous sections would need to be addressed.

On the palm seed front, compared to high yielding oil palm regions in Malaysia and Indonesia, which receive an average rainfall of 2,000 mm on an annual basis, coastal areas in Pakistan receive 32.1 mm per year on average. This is a vast difference, but it has been suggested that acre water requirement of oil palm is lower than that of sugarcane and banana plantations currently grown in Sindh’s coastal belt. Because of this, the SCDA suggests relying on irrigated water to explore the potential of oil palm plantation. Irrigated water supply is also being harnessed to expand oil palm plantations in India.

At the end of the day, however, the most important factor will be whether or not there is enough political and bureaucratic will to focus on this issue. Up until now, efforts to completely localise oilseed production have been half-hearted and imperilled by a lack of attention. As Pakistan heads into a time of trying to save anything and everything from any possible source, this is one area that could very well prove a model example if handled properly.

All graphs have been taken from the SBP’s report for the first quarter of the financial year 2021-22.

Domestic olive oil. Phir biogas ka bandobast, foren.

On the 2nd of June this year, Finance Minister Miftah Ismail ordered that the process of importing edible oil from Malaysia and Indonesia be facilitated to ensure smooth supply of the commodity to the consumers and stabilise its price – which had been hiked by more than Rs 200 a day before.

Very Gud Info In This Post ….!!!!

Yes Very Gud Info In This Post ….!!!!

Gud Info in This Post … !!!

yes very Gud Info in This Post …!!!

Thank you for this nice post and wonderful read!

It is not my first time to pay a quick visit this web page, i am visiting this website dailly and get fastidious information from here daily.

온라인 카지노

j9korea.com

Nice content!