Sajid Mahmood trudges through his cotton fields in Mirpur Khas. As he makes his way from one end of the field to the other, wading through nearly knee-deep water, there is an overwhelming realisation that it is a walk of complete desolation. His entire crop for that year has been destroyed. The rains have swept away upwards of around Rs 1.6 million worth of cotton from his land. Sajid will have to abandon his flooded fields until next year when they are ready again, and work on theqa for someone else in the meantime.

He is one of the lucky ones. His house’s roof has holes and is ankle-deep in water but it still stands. None of his family has perished even though some have lost their homes. In other areas, the picture is much more terrifying.

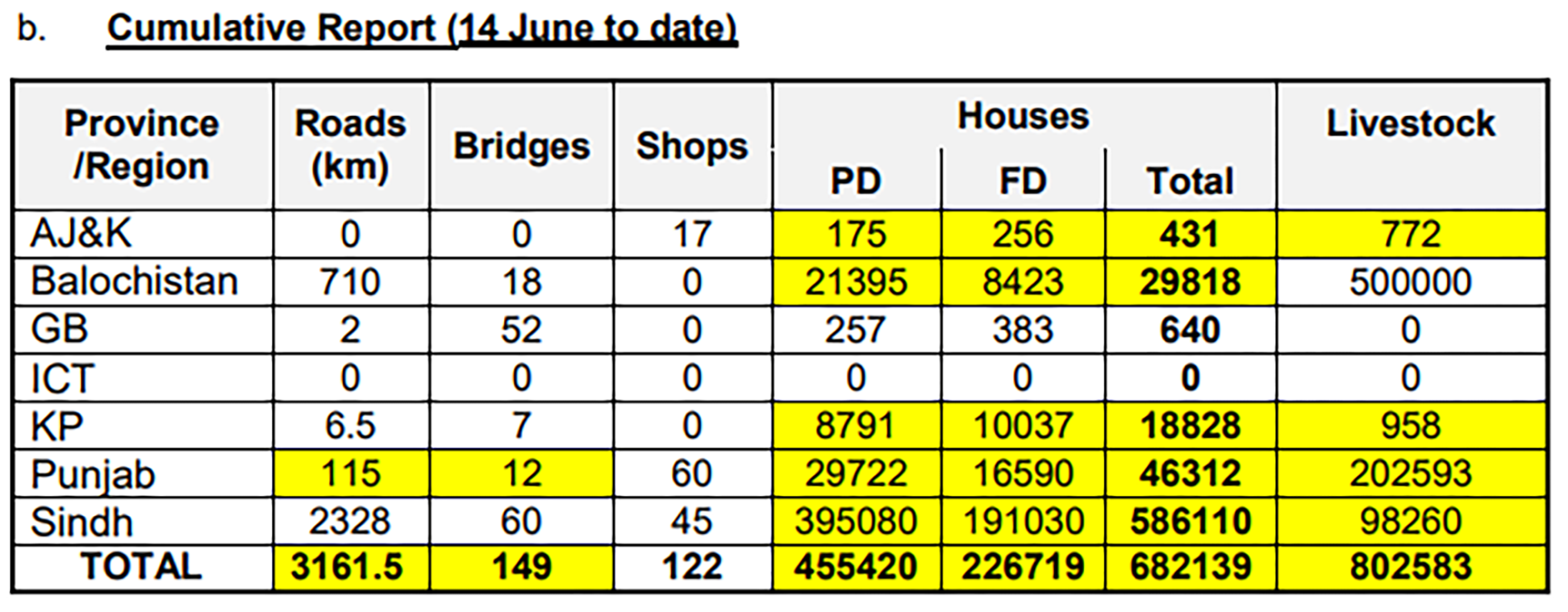

Only 56 kilometres away in neighbouring Sanghar, the entire district has been submerged in water nearly five feet deep in areas. The entire village of Chak 7 has been displaced and wiped out. More than 100 kilometres away in Sukkar, a similar story of devastation reigns. These are just a few pictures of the misery that the still raging floods in the country have caused. Outside of Sindh, Balochistan finds itself with more than 50,000 houses lost and nearly as many damaged, and more than 700,000 acres of crops worth around $10 million destroyed across the province.

By all accounts, both from government officials and non-governmental organisations, the flooding that has laid waste to huge parts of the country over the past couple of months is as bad if not worse than the flood disasters of 2010-11.

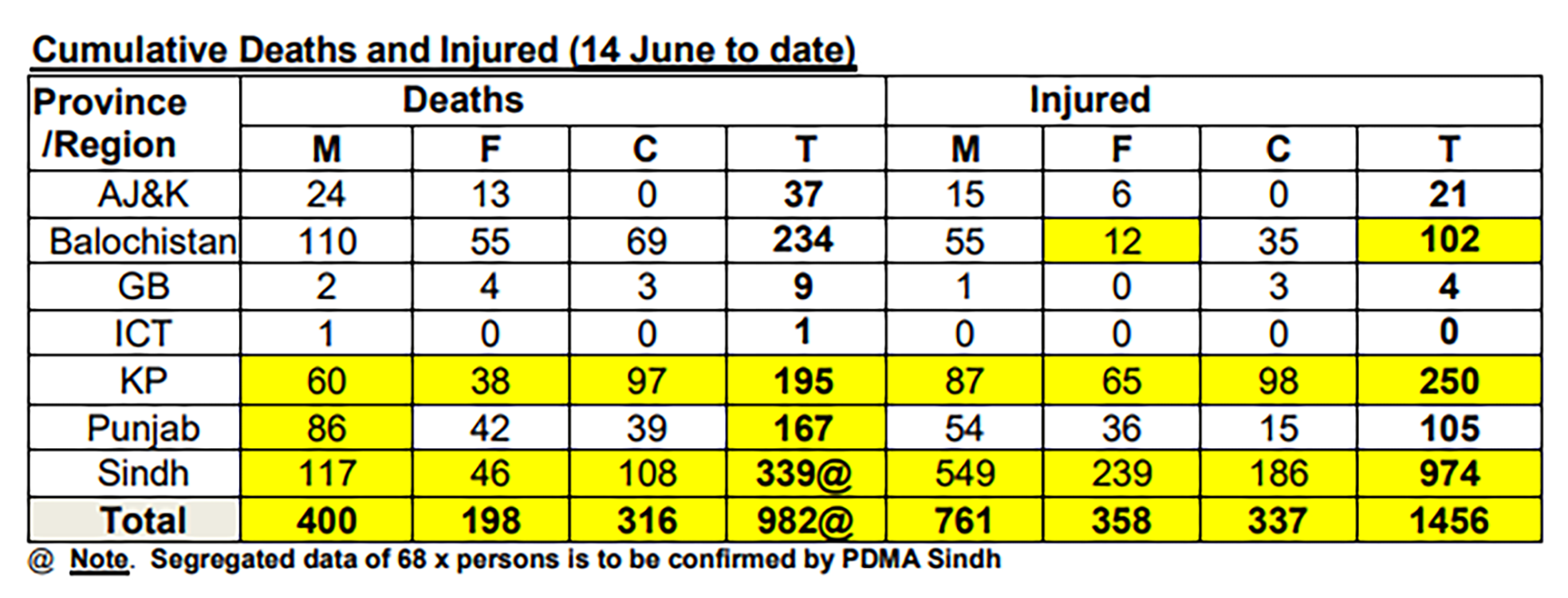

With nearly a thousand casualties reported, the floods that have lashed Sindh, Balochistan, vast swathes of Southern Punjab, and now KP have caused insurmountable human and ecological damage. And while the loss of human life and the immediate provision of relief to all displaced and affected people is the need of the hour, these floods have also ransacked the economy.

The overall impact is difficult to measure. The on-ground situation presents a bleak picture, and with the rains and floods still refusing to ebb, it will be days before a tally of lives lost, crops destroyed, and livestock washed away can be tabulated. In the meantime, educated guesses from government sources put deaths in the thousands, millions of acres of agricultural land damaged, and nearly 10,000 livestock animals lost.

In Sindh, Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah has estimated that 90% of all farmers in the province have had their entire crops damaged or entirely destroyed. With a similar situation prevailing in both South Punjab and KP, it means the breadbasket regions of the country have been devastated. In the months to come, food inflation is expected to see a sharp rise on top of which Pakistan will be forced to import food items.

Perhaps most relevant to the economy, the flooding has directly hit the ‘Kapas belt’ of the country — the region stretching from South Punjab all the way into Sindh towards the Indus Delta where cotton is the primary crop. Cotton is grown in the Kharif period, which constitutes the monsoon months from May to August. The destruction that this rain has caused in this period means the cotton crop has faced a major setback. This might be detrimental, since the cotton crop is a major export oriented crop for Pakistan. The secretaries of both the Pakistan Cotton Ginners Association (PCGA) and the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) have expressed serious concern over what will become of the industry in the year to come.

With food inflation set to rise, and the PCGA estimating that 70 million bales of cotton needing to be imported in the coming year, these floods will have lingering and potent effects on the economy in addition to the immediate human cost. Of course, at the centre of all this are the record rains that have overwhelmed our disaster management system which had already been in tatters. As Pakistan stares down the barrel of the climate change gun, the question on everyone’s mind is the same: what do we do about it?

What the economic devastation will look like

Nearly a thousand people have perished in these floods, and those are only the confirmed numbers. Nearly 70,000 people have lost their homes, at least 3200 roads and 149 bridges have been destroyed, while upwards of 80,000 livestock animals have died in the floods. Recovering from this will be economically devastating as it is. But there might be a larger long-term problem caused by these events that will linger and continue to bleed people dry; crop damage.

As the situation became dire in August, and the Sindh chief minister’s estimation that nearly 90% of all crops had been destroyed became public, the ministry of finance released a warning. Q block said that the recent floods/torrential rains during July and August would adversely affect the standing Kharif crops, specifically cotton, which may impact economic outlook through agriculture performance.

“Recent floods driven by exceptionally heavy monsoon rains have reduced the potential output of both main and minor Kharif crops, thereby tempering the positive outlook of the agricultural sector,” said the ministry’s Economic Adviser’s Wing in its Monthly Economic Update & Outlook for August. “Assessment of the crop damages is in progress by the provinces; however, significant losses can be witnessed. The present situation depicts water inundated cotton fields mostly in Sindh, Balochistan and southern districts of Punjab,” it added.

The cotton crop will be very important in this situation. While cotton has largely been left to its own devices in the past 15 years since the 2008-09 financial crisis momentarily crippled the textile industry, it is still a major contributor to Pakistan’s exports. And since we desperately need the foreign exchange from these exports, it means the impact will be all the higher. Pakistan currently does export cotton, but more important is the cotton that is used by the local textile industry to produce clothes that are then exported from Pakistan. The timing of these floods, of course, have been particularly ironic since Pakistani cotton had seen signs of recovery this year for the first time since at least 2015.

In the secondary sector, the cotton-based textile industries have a 21% share in large-scale manufacturing and consequently a 2% share in the national GDP. For decades, the textile industry thrived on the back of local cotton being easily and readily available. However, because of the decline in the cotton crop because of both climate change and the brief collapse of the textile industry, cotton began to be imported to Pakistan as well. However, this had gotten too expensive for the industry since the beginning of the pandemic when international prices of cotton shot up significantly, which is why they once again fell back on local cotton and farmers also began to grow more of it. The problem is, however, that with the ‘Kapas Belt’ so singularly affected, they will once again have to rely on expensive imports which will be another blow to the balance of payments.

While cotton farmers are already in a state of desolation, the textile and cotton ginning industry is sitting with bated breaths. All they can do right now is hope for the best, and the effects of this will only become apparent in a few months, but they are clearly worried. APTMA Secretary General (North) Raza Baqir, for example, believes that based on the reports received from the media regarding the cotton crop damage, there is a lot of concern in the industry. And while it is too early to make any final judgements, there has been a wave of concern ever since the news came out.

“A few media outlets have reported that the government is going to conduct a survey in this regard, and the situation won’t be very clear until such a report comes out. Cotton prices are currently on the rise across the world and countries like China are also facing low cotton production. In Pakistan too, the per mound price of cotton has increased compared to last year. In such a situation, there is undoubtedly the fear of increasing the import of cotton,” he said. “If that happens, the picture won’t be pretty for the industry.”

“Cotton has become expensive. On top of this, fuel prices mean purchasing power has gone down. The demand for cotton is there but not as much as it should be because we’ve been hit by a double whammy, and on top of that there is now this concern for the cotton crop as well,” says Asif Khalil, Chairman of the Pakistan Cotton Ginners Association. At the current rates of cotton, worldwide consumption will continue to decline. Cotton mills are shutting down due to high prices.”

“The price of cotton per 40 Kg has reached Rs 23,500, which was also very high last year but stopped at Rs 22,000. If we talk about the cotton cultivated in Pakistan, it will not have much impact in the beginning. We are due to release the cotton figures on September 3 and my own view is that they will be the same as last year for now. But there will be an effect. We will need to import approximately 70 million bales of cotton this year. Mills will also find that if the yarn is not available cheaply, they will go to lower production or switch to an alternative fibre if it becomes cheaper. This will decrease our competitiveness on the international market.”

The market players are worried, and cotton’s impact could be huge on our upcoming financial outlook. With associations, farmers, and the finance ministry all in a sweat over this, the picture is bleak. On top of all this, there are also reports from farmers that food crops have been severely compromised. Since it is currently the tail-end of the Kharif period, it means that crops such as rice and maize will be under pressure. With the economic outlook generally poor as well, especially with global and domestic uncertainties abound and worldwide inflation high, the added pressure on crops may mean a rise in food inflation in particular.

The anatomy of the floods

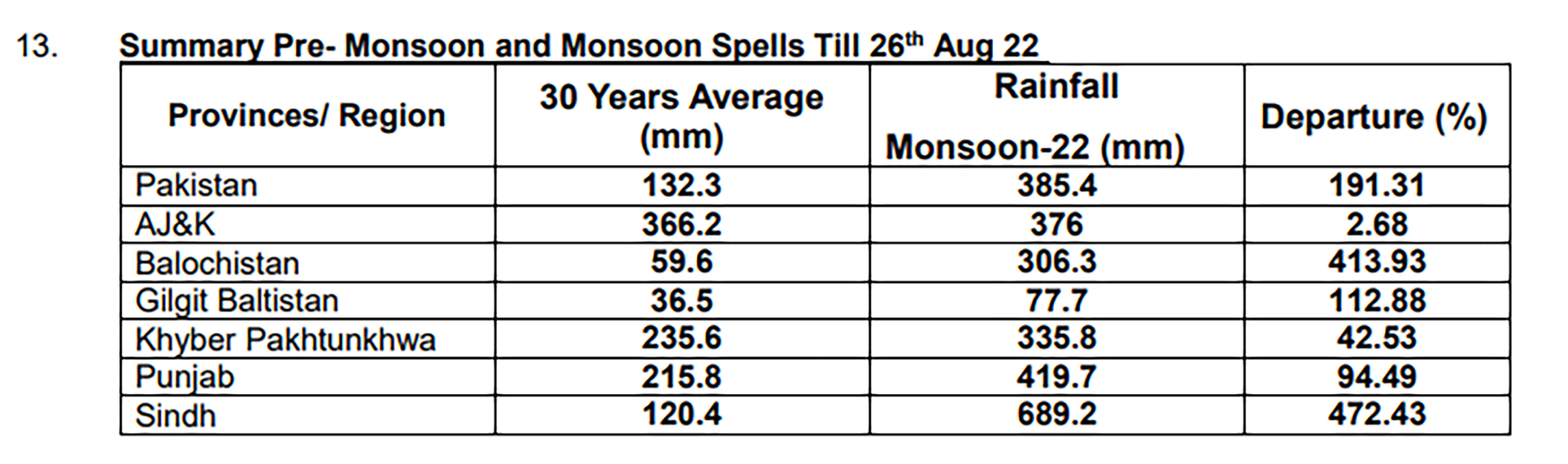

In short, climate change has resulted in a gargantuan increase in the amount of monsoon rainfall that Sindh and Balochistan have seen this year. The two provinces saw the highest amount of water fall from the skies in living memory, recording 522 and 469 per cent more than the normal downpour this year according to the met department. “Sindh has received 680.5mm of rain since July when the monsoon season actually began,” said a Met official.

“As per calculated and defined standards, Sindh normally gets 109.5mm of rain in the monsoon season. So it’s 522% higher than normal. Similarly, Balochistan receives 50mm rain on an average every monsoon, but it has so far recorded 284mm — 469% higher. The country has overall witnessed 207 times higher rainfall so far this monsoon and the season is going to last till September-end.”

The main reason behind the flooding has been this abnormally high rainfall causing hill torrents — which are a distinct type of waterway in which water drains from the mountains and hits localities and infrastructure in its path at an enormous speed. More than 200 hill torrents originate from the west of Suleiman Range and hit Taunsa, Dera Ghazi (D.G.) Khan and Rajanpur Districts of Punjab in Pakistan. Among these, 13 hill torrents have large catchment areas and flood potential. All of these have realised this potential this monsoon season at the same time. The discharge at Taunsa, Guddu & Sukkur barrages is more than Twice that of Kalabagh and Tarbela, showing that the additional water is coming from Koh-i-Suleman hills and torrential rains. Dams would not have stopped this overflow, particularly since the Indus is not overflowing, it actually has levels of water.

This has caused destruction in Balochistan and South Punjab, with the rains and a swollen Indus river delta wreaking havoc in Sindh. In KP, meanwhile, flash floods coming from fast melting glaciers have overrun shoddily and dangerously built constructions on the banks of rivers. The main cause behind the flash floods has been the inflow of heavy rains and a massive river current from the Kabul river that has overrun the province. In KP, in fact, while the Kabul river swelled because of excessive monsoon rains, with KP recording a 50% increase in the level of rain, one of the major reasons for the flash floods were cloud bursts in the Swat and Mingora regions that overran the Swat river and swept away hotels and buildings on the embankments. The met department, according to an anonymous source, did not pick up on the the cloud burst and issued no advisory for it.

In Northern Punjab on the border with KP, the situation is balanced precariously, with military and NDMA officials on high alert in the Kalabagh and Chashma regions where the met department has issued a flood warning ranging between 5,50,000 Cusecs to 7,00,000 Cusecs over the next 24 hours (as of Saturday).

According to the Sindh Chief Minister who based these estimates on the recent census, this means that more than 10 million people were possibly displaced. In villages, nearly 1.5 million homes have been destroyed entirely. In at least 23 districts, the rains have destroyed all crops, and 90% of farmers have lost their entire crops on more than 2 million acres. While the CM said that it was difficult to measure livestock, some data has come through from the PDMA which estimates that tens of thousands of livestock animals have perished in the hill torrent flood. The size of catastrophe has not been seen in the province in living memory.

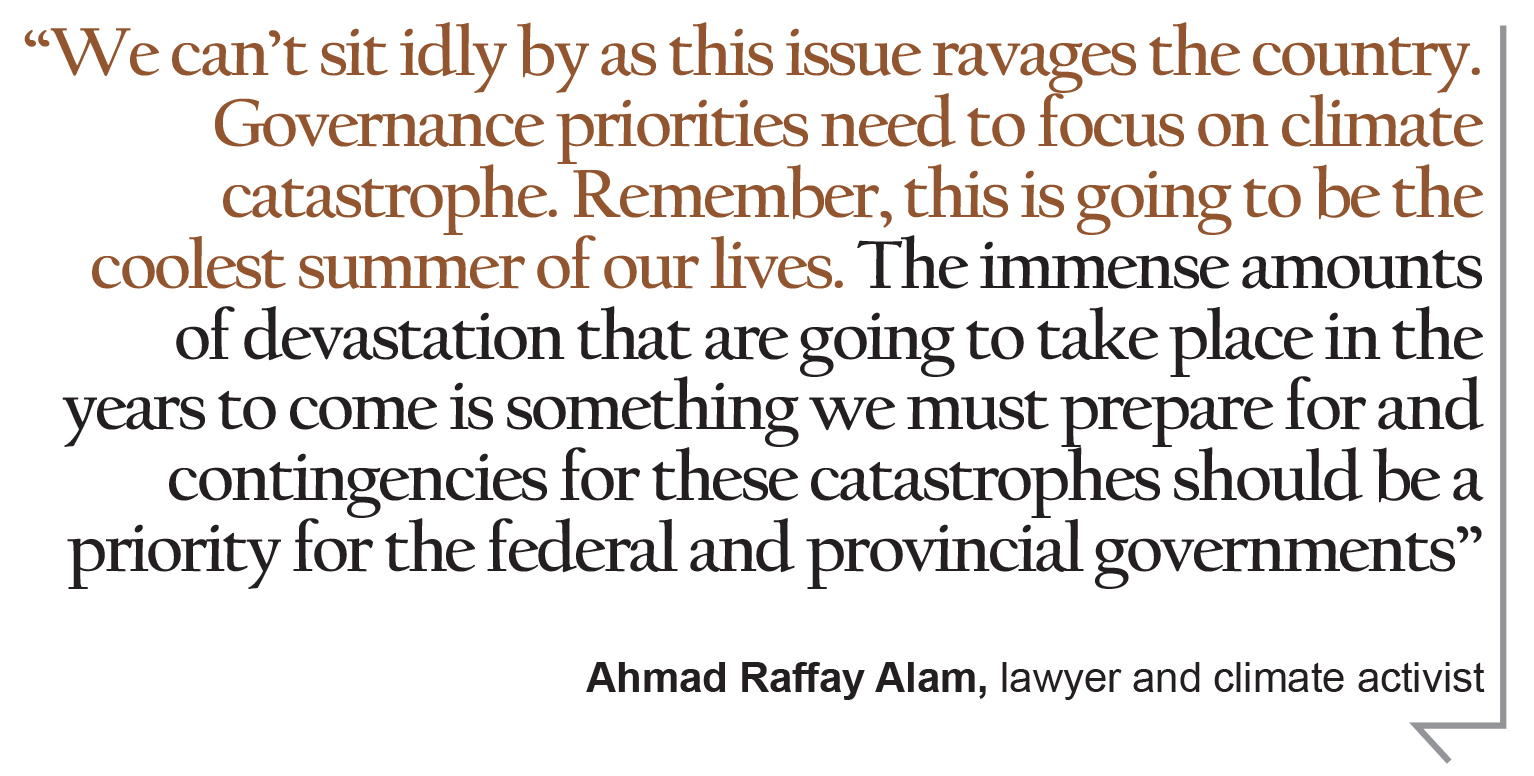

All of this has raised concerns among environmentalists, who have been raising alarms over the fast changing weather patterns in the country. “It is not easy to attribute every flood to climate change. But Sindh has received a ridiculous amount more rainfall than average. The definition of climate change is unprecedented weather conditions in a pattern. This looks very much like climate change,” says Ahmad Raffay Alam, a lawyer and climate activist based in Lahore.

“There are two layers to the problem. Addressing the climate crisis on a national basis is sub-optimal. This is all because of global economic activity over the past 200 year. This is a man made disaster caused by the global north’s emissions. At the same time, we can’t sit idly by as this issue ravages the country. Governance priorities need to focus on climate catastrophe. Remember, this is going to be the coolest summer of our lives. The immense amounts of devastation that are going to take place in the years to come is something we must prepare for and contingencies for these catastrophes should be a priority for the federal and provincial governments.”

“This is the biggest issue faced by Pakistan and indeed the entire earth and human civilization right now. This will cause food shortages next year, especially with heat waves in China and the global north. Immediate action is needed.”

The climate crisis

It is real. It is here. And it is already too late to avoid the disasters that we will face ahead. But that does not mean there is nothing to be done. Pakistan must go forward with a two-pronged strategy. The first part of this strategy must be focused on mitigation. As the global north continues on its path of apathy after causing the global climate crisis, these disasters will happen and our government must be prepared to deal with them when that happens. The second part of the strategy will be more actively calling for climate reparations and making a better case for Pakistan to be on the path to climate recovery through international consensus. Here is what all of this means.

The first part of the problem must be dealt with first. As Alam pointed out, we can’t sit idly by as this issue ravages the country. The government must recognise publicly that Pakistan is in the middle of a serious climate change crisis, and must declare a climate emergency. This does not mean immediately cutting down emissions, since that is a global issue, but first and foremost preparing for possibilities such as the one we are seeing right now. Emergency services must be revamped with a view to climate change, and more funds must be allocated towards this cause otherwise we will see a similar situation in the very near future. It also means focusing on better planning and development in the country.

In an exchange with climate minister Sherry Rehman, Dr Nida Kirmani, a professor at LUMS, argued that the immediate concern was not about emissions. “It is about unsustainable construction, a lack of appropriate infrastructure, and a clear disaster management strategy. This should not be seen as an attack on your ministry but on the mismanagement of several governments over the years.”

Then there is the second prong of how this issue should be addressed. Essentially, Pakistan is ranked eighth among countries most vulnerable to climate crises despite contributing less than one percent to global carbon emissions, according to the Climate Change Risk Index 2021. According to the Centre for Global Development, developed countries are responsible for 79% of historical carbon emissions. Yet studies have shown that residents in least developed countries have 10 times more chances of being affected by these climate disasters than those in wealthy countries. Further, critical views have it that it would take over 100 years for lower income countries to attain the resiliency of developed countries. Unfortunately, the Global South is surrounded by a myriad of socio-economic and environmental factors limiting their fight against the climate crisis.

None of this takes away from the fact that Pakistan, like other countries, has a major emissions issue, however, there is a difference between allocating emissions and allocating responsibility for those emissions. The developed world has a massive emissions debt that it must pay to the developing world for the damage it has caused them. One of the real sore points has been climate funding worth $100 billion that was promised more than a decade ago. The promise was made 12 years ago, at a United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, where rich nations made a significant pledge. The pledge was to put in $100 billion a year towards less wealthy nations by 2020, to help them adapt to climate change and mitigate further rises in temperature.

That promise was broken.

Figures for 2020 are not yet in, and those who negotiated the pledge don’t agree on accounting methods, but a report last year for the UN1 concluded that “the only realistic scenarios” showed the $100-billion target was out of reach. “We are not there yet,” conceded UN secretary-general António Guterres.

As a country, we have been given a poor lot in life on the climate front. The actions of others have resulted in serious consequences for us. It is unfair, but it must be fought. If we are not quick in acting and preparing for the future, the harrowing sights we are seeing right now will become commonplace in the years to come. People will continue to lose lives and homes. Climate refugees and internally displaced climate refugees will live unbearable lives. The economic depredation will continue, which will once again hit the people. It is already too late to avoid this. Climate change is here, and it will stay. The best we can do is prepare to our best abilities, and keep fighting for climate justice.

Additional reporting by Shahab Omer and Taimoor Hassan.

I adore your websites way of raising the awareness on your readers

Nice Article by Abdullah Niazi and the best article about catastrophe in Pakistan

70 million bales import? seriously? please check your numbers before you publish

I have perused every one of your posts and all are exceptionally enlightening. Gratitude for sharing and keep it up like this.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com