Amidst a largely bleak period, a donor’s conference held in Geneva presented a rare bright spot for Pakistan where donors pledged close to $ 10 billion in funding over the next few years to help the country rebuild from devastating floods.

The funding is meant to not only just rebuild, but also to introduce climate resilient infrastructure and planning to mitigate such disasters in the future.

However, securing funding and using it effectively are two entirely different challenges. One such example, well before the catastrophic floods of 2022 across swathes of Pakistan, is the case of an internationally funded project that heralded new hope for the country’s largest city, Karachi.

In short, things have not panned out as they were meant to.

Back in 2020, when Pakistan was reeling from its first wave of Covid-19, the country’s largest city was hit by record rainfall that left most of the city underwater.

‘Saving’ Karachi

Karachi is no stranger to apocalyptic urban flooding. But the 2020 floods were something else – and injected new impetus into solving the city’s seemingly continuous flooding problems. A major problem was trash clogging the city’s nullahs – narrow channels that drain wastewater from the city to the sea.

Though it sounded simple enough, fixing this issue was going to be an expensive proposition in a country that spends most of its money on defence and debt. So when it was announced, the World Bank’s Solid Waste Emergency and Efficiency Project (Sweep) was seen as a lifeline that would help Karachi with its urban flooding nightmare.

The five-year project brought with it $ 100 million in funds, with the aim to “mitigate the impacts of flooding and COVID-19 emergencies, and to improve solid waste management services in Karachi.” Sweep was supposed to help solve the problem of trash clogging the nullahs, leading to stormwater overflows, by improving solid waste management.

“In 2019, when the Sindh Government took the issue to the World Bank, we realised that there was a serious requirement to clean the nullahs once or twice a year,” Sweep director Zubair Channa, a Sindh government official, said.

After bad urban flooding in 2020, the Sindh government reached out to the World Bank to speed up the cleaning of nullahs. “We asked to be allowed to work and they agreed, so despite Sweep not having been signed yet work began, and we were to get the money back through retroactive funding,” Channa said.

The World Bank announced the decision to finance these efforts in December 2020, saying they would “improve solid waste management services in Karachi” and “upgrade critical solid waste infrastructure”. This would help to reduce floods “especially in vulnerable communities around drainage and waste collection sites.”

The reality on the ground was different.

Ground realities

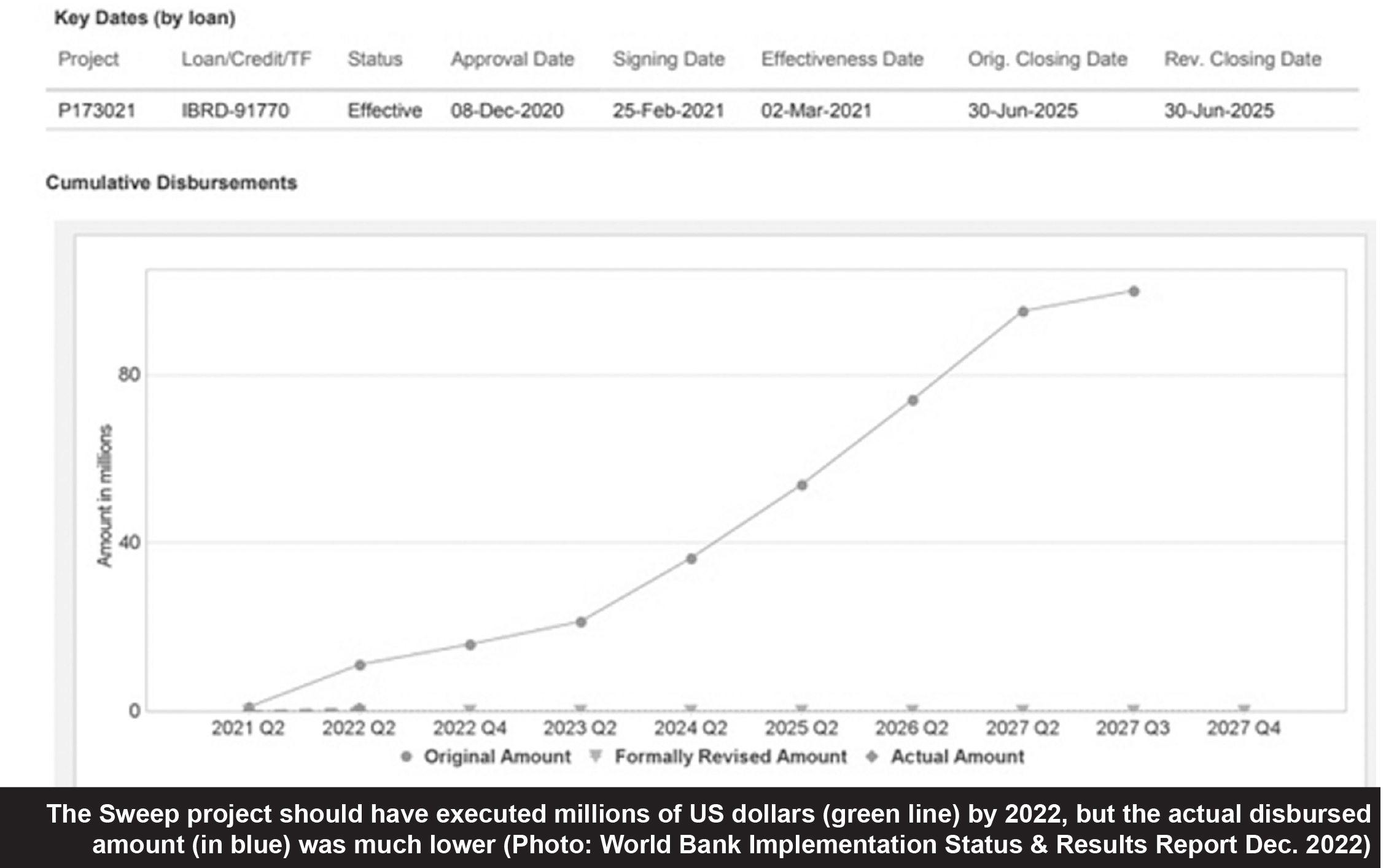

Two monsoon spells later, however, it seems the project has had little effect, with flooding upending the city in both 2021 and 2022. Two years into the project, there is no sign of progress and less than 3% of its $ 100-million budget has been spent – none of it on new infrastructure.

The people who were supposed to benefit from the efforts to stem urban flooding, and those who were most susceptible to its effects, have seen no benefits.

“We never know what kind of damage to expect when it rains,” said Razia Sunny, who lives by one of Karachi’s nullahs. “Residents here have gotten sick because of the waste flooding into our homes during urban flooding, we’ve even had people slip and fall [into the nullahs],” Imran Gill, another resident of the informal settlement, said.

“We never know what kind of damage to expect when it rains,” said Razia Sunny, who lives by one of Karachi’s nullahs. “Residents here have gotten sick because of the waste flooding into our homes during urban flooding, we’ve even had people slip and fall [into the nullahs],” Imran Gill, another resident of the informal settlement, said.

One thing that did change for the millions of residents of slums along Karachi’s winding nullahs was that they came into the crosshairs of a Sindh government drive to clear settlements along the waterways. Provincial authorities took the promise of funding as a cue to demolish thousands of homes without, residents say, any consultation or plan to find them somewhere else to live.

For the purpose of this story, dozens of official documents were reviewed, officials inside the projects were interviewed and sites affected by flooding were visited. In the sites near Karachi’s sewage infrastructure, there are several cases where residents of informal housing got injured or even died during extreme floods in 2020 and 2022.

When human rights organisations raised concerns about the demolitions, the World Bank distanced itself from the project. Government officials insist things are not going too badly. “We’re only delayed by three or four months,” Sweep director Channa said.

The World Bank seemingly agrees: Its project reports in March 2021 and November 2021 declared progress “satisfactory”, even though no work had been completed on the ground. This rating changed to “moderately satisfactory” for both the June 2022 and December 2022 reports, after further inaction.

In response to a request for comment, the World Bank defended the project and said the consultancy was “fairly advanced and expected to deliver their outputs soon”.

“Based on the current schedule, we expect the construction of the waste disposal facility and transfer stations to commence in early 2023,” said the bank’s press office.

This is a climate adaptation issue. Global heating “likely increased” the intensity of monsoon rains in 2022, when flooding hit 33 million people across the country, an international group of scientists found. More extreme events are expected under a 2C warming scenario.

The money trail

So what has happened to the promised funding? The money comes in the form of loans to the provincial government of Sindh.

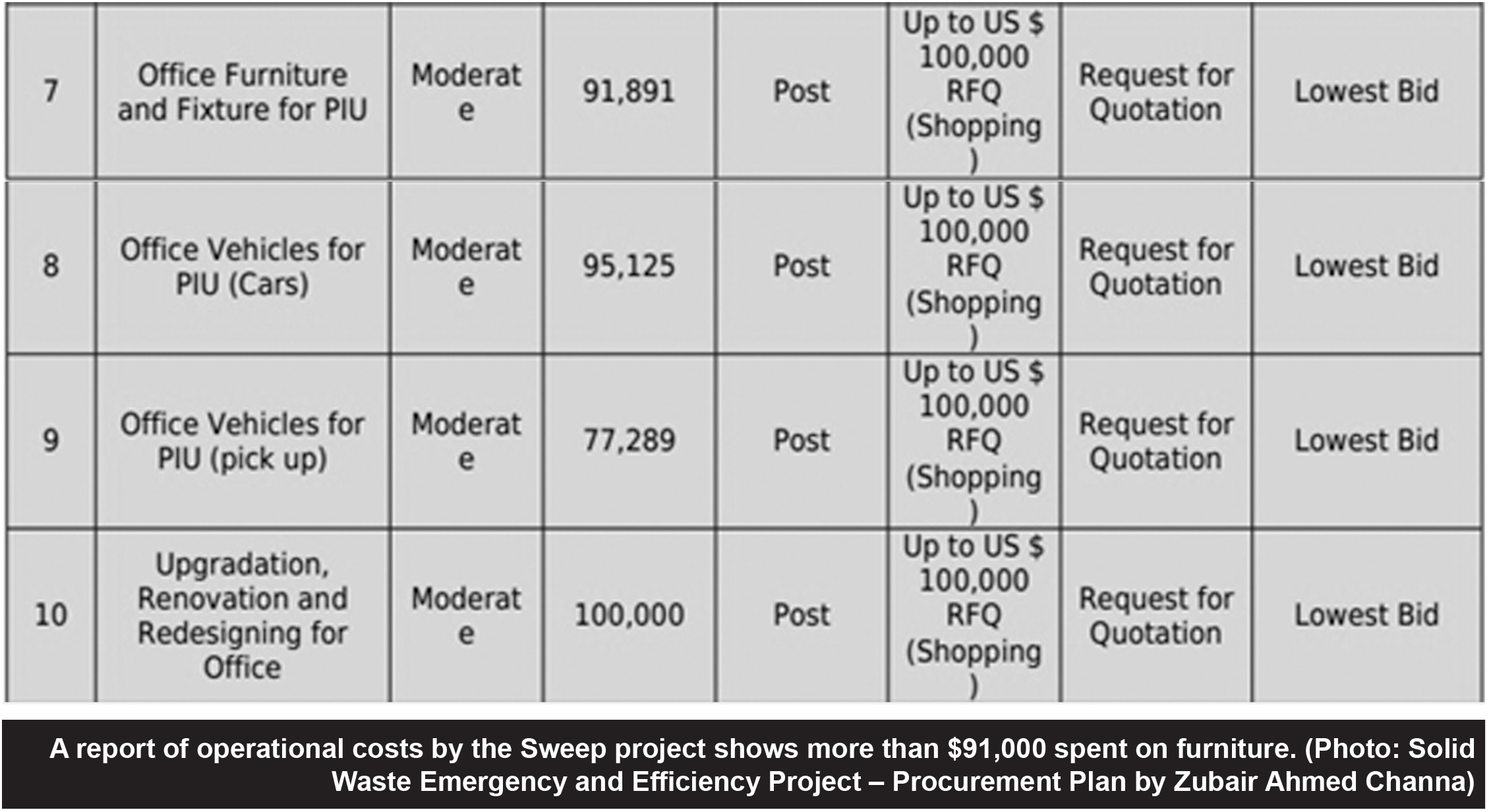

Among a few feasibility studies and some operational costs, documents show the authorities have so far spent $ 91,891 (which at the time was converted to almost Rs 16 million) on furniture. An official source associated with Sweep, who asked not to be named, said the number was too high and seemed out of place.

“We’re a poor country; we can’t afford to spend like this on operational costs, not when that money will be paid back by citizens who already can’t afford it,” said architect and urban planner Dr Noman Ahmed, chairperson of Department of Architecture and Planning at the NED University Karachi.

The Sindh government’s procurement plan earmarks $ 8 million for equipment ranging from bins to waste collection vehicles. Another $ 30 million is destined for implementation “works”. This money has yet to be disbursed.

On all aspects of these expenses, bank oversight is meant to come once the project is concluded. Yet related projects raise red flags. In November, the Sindh High Court barred the provincial government from awarding any more contracts under the World Bank’s Competitive and Liveable City of Karachi (Click) project, citing a lack of transparency over where the money was going.

Fahad Saeed, South Asia and Middle East lead at the policy NGO Climate Analytics, said: “Pakistan needs to do some introspection as to why they were unable to tap into the funds that were available. Was their own house in order to access these funds?”

In 2021, the world’s governments agreed at COP26 to double the amount of international adaptation finance by 2025, which stands at around $ 20 billion per year.

Destroyed homes

Instead of protecting the vulnerable, the provincial authorities started by bulldozing homes that had been built without planning permission. The World Bank denied responsibility. “There were meetings between civilians and WB officials, who claimed to us that they had never sanctioned any encroachment removal,” Zahid Farooq, senior manager at Karachi’s Urban Resource Centre, said.

The World Bank’s press office said their projects “will be prohibited from financing any future investments on the affected nullahs. Sweep will not retroactively or prospectively finance any nullah cleaning works, or any studies related to the nullahs.”

Then, in 2022, extreme flooding hit informal settlements the hardest, turning the water filled area around the nullahs into quicksand, according to resident Gill. “No one has ever died because of the nullahs before all this construction took place. And yet, the area has now seen several people lose their lives.”

Bhutta Masih died in flooding when the ground beneath his feet went out. He leaves behind five children and his widow, Parveen. His youngest son helped pull his father’s body out with ropes and has found it difficult to recover from the trauma. “He used to have a job but lost it. He hasn’t been okay mentally since that day. We can’t afford this,” Parveen said.

Owners of the broken homes are not permitted to rebuild what remains of their homes – even by hanging curtains. But some have nowhere else to go. Ruksana and Sadayat, a couple in their 80s who have lived most of their lives on the nullahs, used broken bricks they found to do some repair work. “We know they can break this down, but we have no other choice but to rebuild it. We can’t afford the rent [elsewhere], and when they come to tear it down, they will tear it down. What can we do?” Ruksana asked.

Sweep’s future

Despite all its troubles, Sweep director Channa said that Karachi’s flooding wasn’t as bad as previous years. Urban planning expert Ahmed said this was “completely untrue” and infrastructure under the World Bank’s Competitive and Livable City of Karachi (Click) project had caused flooding to worsen. “They’ve done improvement projects, for example, the green belts, which themselves created bottlenecks,” he said. “It seems that this was nothing more than an emergency cleaning effort with no long-term thought process for solutions. When the WB is intervening with such a large portfolio, why aren’t they providing a plan to help the people who are being displaced?”

Lawyer and activist Abira Ashfaq has worked with the affected communities. She said the World Bank failed to use its influence on the Sindh government to help people living on the nullahs.

“We filed a complaint with the WB, and they deemed our case eligible. We held five meetings with WB officials and with the stakeholders,” she recalled. “Nevertheless, they distanced themselves and said their project was only meant to address waste disposal, and they eventually dismissed our complaints, claiming no responsibility,” she said.

The result of this interaction was that the nullah cleaning work was once again thrown back to the Sindh government, which has now handed it over to the Frontier Works Organization (FWO), the engineering wing of the Pakistan Army.

For now, residents can expect little more in the way of flood aid than tarpaulins from local NGOs to cover their damaged homes. They rely on each other and wait for the next flood.

A version of this article originally appeared in Climate Home News.

Ab Allah hi Pakistan ko bacha sakta hai.

Nice knowledge gaining article. This post is really the best on this valuable topic.

온라인 카지노

j9korea.com