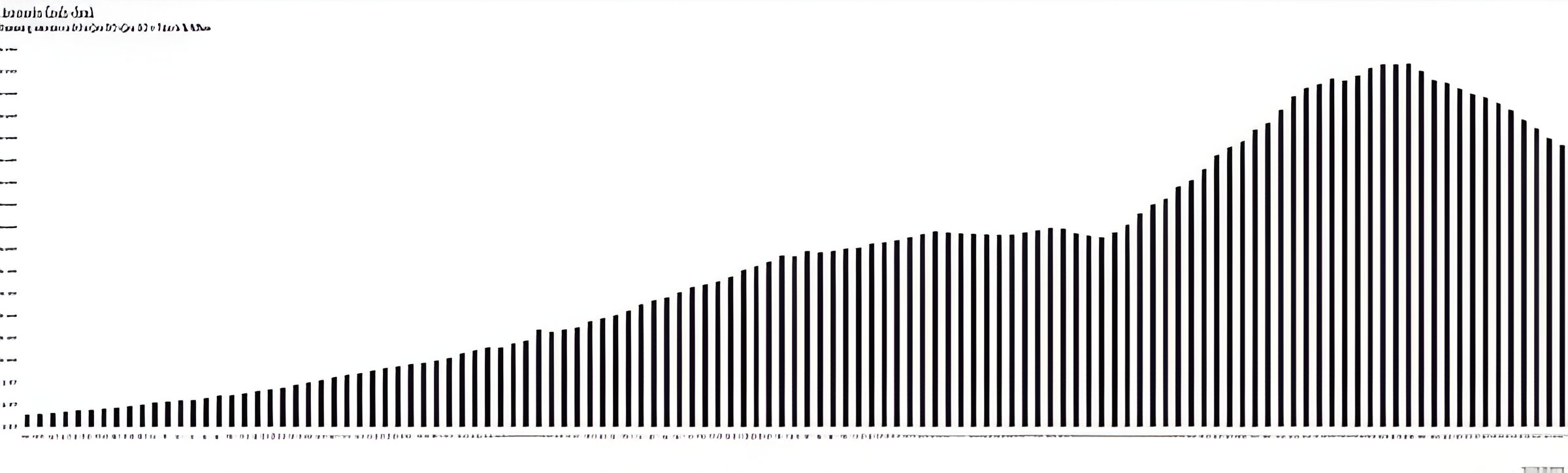

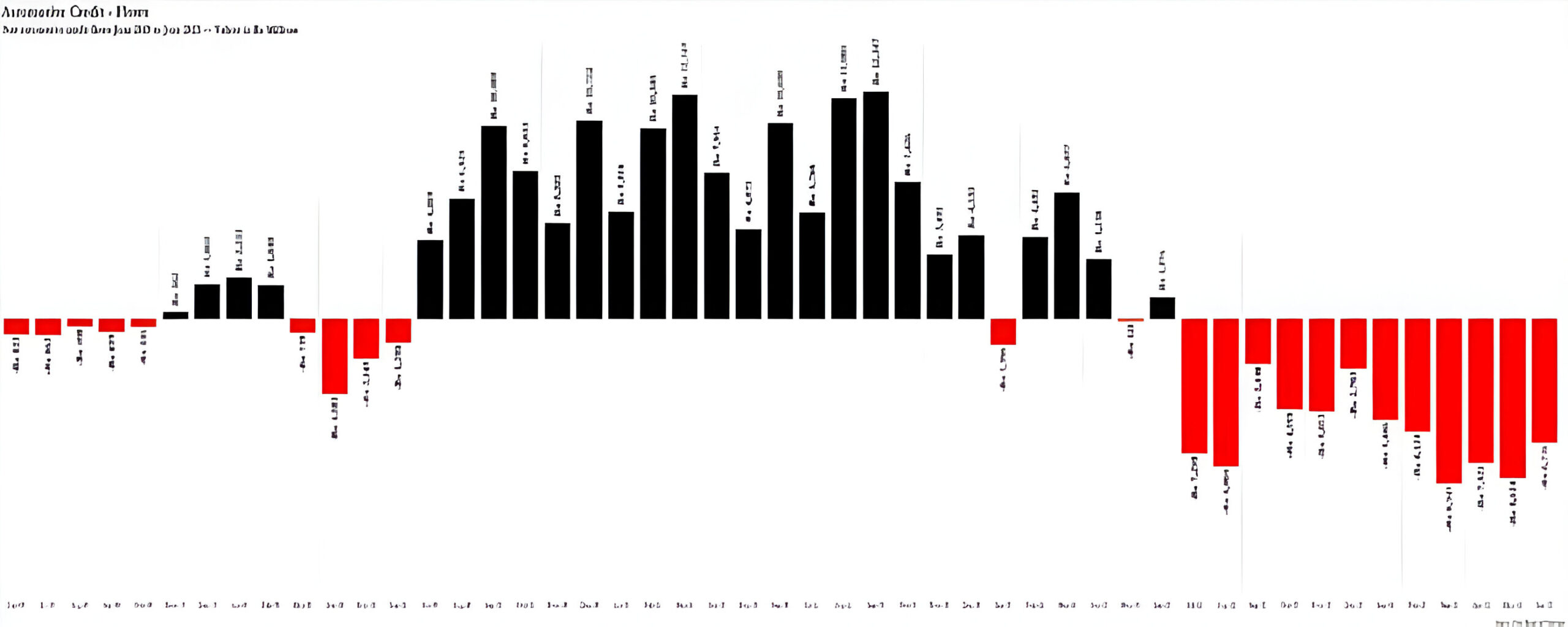

The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) recently unveiled its credit data for June 2023, heralding the conclusion of a precarious fiscal year for automotive lending. Outstanding credit now stands at Rs 2.94 trillion — the lowest it has plummeted since April 2021. Moreover, the SBP’s data divulges that FY 2023 witnessed twelve consecutive months of contractions in outstanding credit — the most successive periods since the tumultuous 2007/8 financial crisis. Net automotive credit contracted by an astounding Rs 74.117 billion.

“The auto industry is facing a long road to recovery,” states Yousuf Farooq, Director of Research at Chase Securities. “It’s going to take years for auto sales, and particularly credit to the auto sector, to bounce back.” Farooq adds that “interest rates should start gradually coming down from 3QFY24, but it all depends on the external account situation. The SBP could also loosen the administrative controls that it has adopted in recent years.

So, what is going on within the industry?

Why has automotive lending collapsed?

First things first. Why are we seeing the worst net credit flows since the economic crisis of 2007/8.

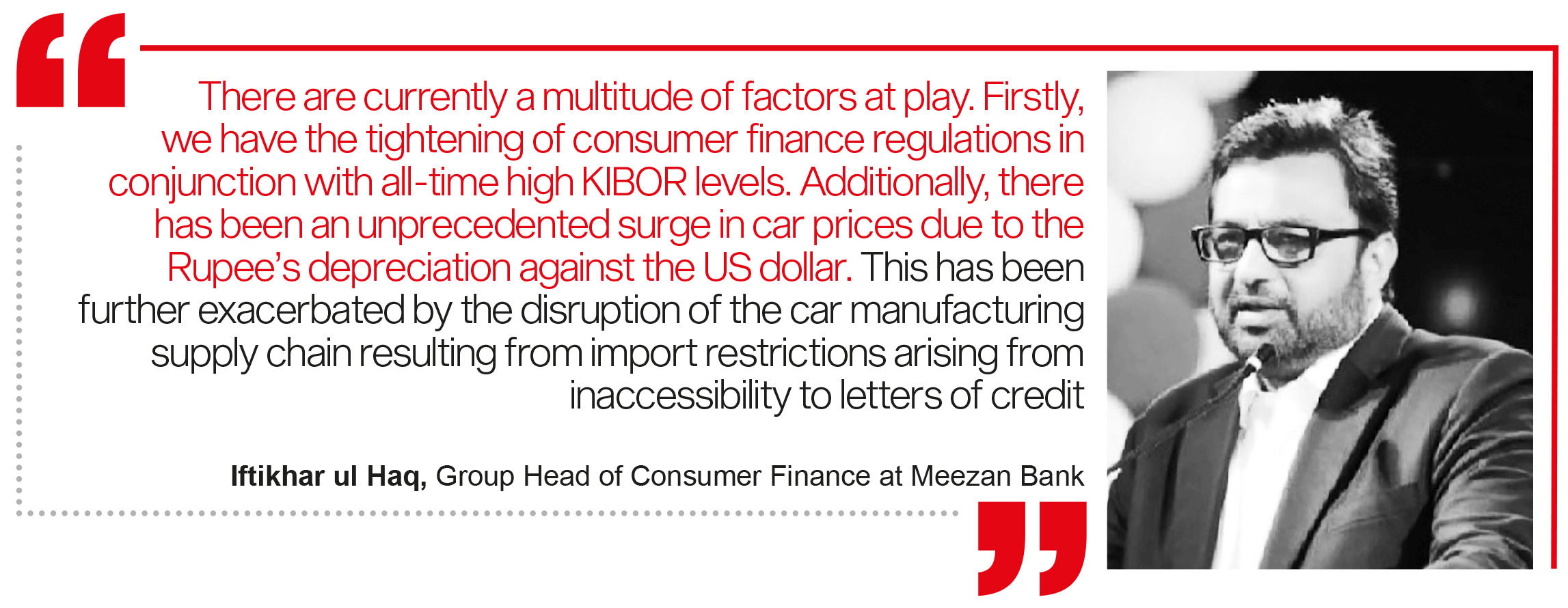

“In fact,” explains Iftikhar ul Haq, Group Head of Consumer Finance at Meezan Bank, “the current crisis is much more severe, as multiple factors have converged simultaneously. In contrast, in 2007/8, the crisis was primarily driven by the elevated Karachi Interbank Offered Rate (KIBOR).”

Haq continues, “There are currently a multitude of factors at play. Firstly, we have the tightening of consumer finance regulations in conjunction with all-time high KIBOR levels. Additionally, there has been an unprecedented surge in car prices due to the Rupee’s depreciation against the US dollar. This has been further exacerbated by the disruption of the car manufacturing supply chain resulting from import restrictions arising from inaccessibility to letters of credit.”

“Inflationary pressures have also eroded disposable incomes,” Haq adds, “while overall political and economic instability and uncertainty have caused customers to defer their buying decisions.”

When asked about the aforementioned regulations that have been tightened, Haq explains, “There is now an upper cap of Rs 30 lakh on industry-wide auto finance exposure vis-à-vis a 100% increase in car prices in less than two years. Furthermore, the lowering of financing tenure and DBR (debt burden ratio) requirements has resulted in the non-affordability of monthly repayments. There are also restrictions on imported (used) car financing.”

So, why did the SBP do all of this? Why did it decide to destroy the automotive lending market? “This has largely happened due to the external account situation,” states Farooq, “To control the situation, it seems that the SBP has implemented a policy to reduce car sales and car financing in order to take some pressure off imports.”

“Administrative measures are generally not an optimal way to control the current account situation,” explains Farooq. He elaborates that “with a high marginal propensity to consume in Pakistan, consumers will spend elsewhere when not allowed to buy a particular product, and the current account situation would not improve.” “However,” Farooq continues, “rate hikes and a free-floating currency were the right measures to get the external account situation under control.”

There’s that. We know what happened. However, this is where it gets interesting. The contractions in automotive lending are not as straightforward as one might anticipate. These contractions can be attributed to a dearth of new loans, as well as premature loan terminations.

Furthermore, even if either of these scenarios is transpiring, why isn’t there a crisis of individuals defaulting on their car loans? After all, Haq has depicted a rather dismal picture of the current state of the industry. These are the more granular, and arguably interesting facts that have emerged when looking back at FY 2023.

Investigating the details

So are there not enough new loans, or is the industry witnessing early terminations? “A convergence of events has transpired,” explains Haq.

“Due to a hike of up to 700-800 basis points in KIBOR within a single year, coupled with the variable rate nature of consumer auto loans and financing, there has been a multifold increase in repayment amounts,” elucidates Haq. “Furthermore, the secondary value of vehicles has appreciated considerably, enabling consumers to pay back their loans and financing prematurely,” Haq adds. “On the other hand,” Haq continues, “demand for new vehicle financing has plummeted by more than 60% due to the aforementioned factors.”

And what about the lack of defaults? That was after all a very significant feature of the 2007/8 crisis.

“The current crisis is more profound than that of 2007/8,” explains Haq. “However, consumers are now much more knowledgeable, credit-savvy, and disciplined, primarily due to the advent of credit bureaus, which were in their infancy back then.” Additionally, Haq notes that “the lessons and hardships of the 2007/8 crisis have prompted banks to approve only creditworthy consumers, enhance their risk acceptance criteria, and implement robust risk, collections, and recovery policies.”

Haq also highlights the role of the SBP in guiding banks through prudential regulations and devising fair market practices essential for building healthy auto financing portfolios. “Moreover,” he adds, “the appreciating secondary market value of vehicles has provided a natural hedge to consumers against default in auto loans. Hence, the option of reselling the vehicle at a much higher value relative to the outstanding liability is always available.”

“Bad loans have generally been lower in this cycle, most likely due to better lending practices and KYC this time around,” states Farooq, concurring with Haq.

Now that we have gone over the crisis of FY 2023, where does the industry go from here? Particularly with expectations of a higher policy rate on the horizon.

Where do we go from here

“The policy rate is already at an all-time high. Any further increase in KIBOR would be detrimental to auto financing and all other industries directly and indirectly associated with it,” warns Haq.

“Most banks have already aligned their business models with the current dynamics,” Haq continues. He elaborates that they have done so “by shrinking their pricing margins, implementing cost control measures, and introducing consumer-friendly product offerings.”

Haq also notes that “banks are now giving due weight to appreciated secondary market car values and customer contributions (down payments) in their credit policies.” He adds that “the ratio of used car financing has risen significantly.” “Improving customer experience and the turnaround time of the credit approval process is becoming a priority,” Haq states. He reveals that “digital initiatives are being undertaken to improve process efficiencies and cope with changing consumer expectations.”