Since the early 1990s, one of the most coveted business opportunities in Pakistan has been owning and operating a power plant. Having the opportunity to ascend to the status of an Independent Power Producer (IPP) has been a dream for many corporations. And after all, it sounds like a pretty lucrative business.

Here you have the opportunity to not just be in one of the biggest sectors in the country, but also have the government as a single, guaranteed client that will want to buy more and more power from you. One would imagine that corporations and investors would be lining up to bid for the solar power plant being planned at Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh.

The plan for the 600 Megawatt project was made by the previous Shehbaz Sharif administration as part of a larger effort to produce up to 6,000 MW of energy through solar power. But in the months since the idea for the solar-powered IPP at Kot Addu was pitched, the government has failed to receive any bids for it.

So why isn’t anyone interested? After all, the Kot Addu project will in effect be the newest and fanciest power plant that Pakistan will have. The paragon of Pakistan’s solar revolution — if someone decides to invest, and actually build it.

The straightforward answer is that the Government has, thus far, mishandled the bidding process. However, the reasons for why they have done what they have till now provides an opportunity to rethink everything about our overarching energy framework so that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past decades with the potential to pile on new mistakes this time around.

Inadvertently, the Government of Pakistan has crafted an opportunity to establish a robust energy infrastructure that could serve the nation for decades to come, if they can break free from their existing modus operandi. If they fail to do so, we risk perpetuating the status quo, with the added twist of public scorn being directed at solar power, rather than the non-renewable power plants currently in operation.

Pakistan’s electricity generation 101

There’s a lot to unpack. Let’s start with how power plants are set up. Three terms underlie Pakistan’s electricity infrastructure: request for proposal (RFP), build-operate-transfer (BOT), and power purchase agreements (PPA).

Whenever the government realises that it needs more energy in the grid, it initiates an RFP. An RFP is an invitation for bids to execute a new project proposed by the organisation that issues it. This is essentially the government soliciting someone to bid for the right to establish a power plant. An RFP is what the Government of Pakistan did for the Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh plant and failed. Twice. But, more on that later.

The bids are for companies to operate a power plant on a BOT basis. Under a BOT contract, an entity — usually a government — grants a concession to a private company to finance, build, and operate a project for a period of 20 to 30 years. BOT contracts are typically used to develop a discrete asset rather than a whole network. Think singular power plants on a need-by-need basis rather than the entire grid. At the end of the specified period, agreed upon in the outsourcing contract, the BOT partner will shift the legal ownership of the project along with its assets back to the client. Once a company has completed the plant, it is then an IPP. So, how does the IPP make money and why did we say that companies lined up by the boatload in the past? PPAs.

A PPA is a long-term contract between an electricity generator and a customer, usually a utility, government or company. PPAs can span between 5 and 20 years, during which time the power purchaser buys energy at a pre-negotiated price. It is the sine qua non of the arrangement.

“These are very common in the power sector because whenever an investor comes in and sets up a large plant, they are essentially committing a very specific kind of investment. It is fixed in terms of its location — they cannot easily relocate the power plant. It is kind of a permanent thing, so PPAs assist in mitigating the investor risk,” explains Dr Ayesha Ali, Assistant Professor of Economics at LUMS.

PPAs exist in Pakistan because it does not have a competitive market for electricity. There is a single buyer – the State of Pakistan. Consequently, our PPAs last 25 to 30 years so that they cover the operational life of the plant. Furthermore, because investing in Pakistan comes with a risk and these plants are expensive to set up, our PPA contracts have been indexed to the dollar.

In essence, IPPs have a guaranteed dollarised return for almost three decades. Do you now see why companies would want to line up? This makes it all the more mind boggling that there have been no bidders for the Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh plant?

The existing solar IPPs

The local solar firms that often come to mind are not Independent Power Producers (IPPs), but primarily Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) companies. These firms facilitate individual solar projects but do not supply power to the grid. EPC companies provide a gamut of services, from system design to equipment installation, and operation and maintenance oversight. However, their role diverges from IPPs, who are directly involved in solar energy production and distribution.

The transition from an EPC to an IPP is a complex leap due to the vast difference in scale. For instance, Reon, one of Pakistan’s largest solar EPCs, manages approximately 200 MW of solar energy, while a single solar plant can boast over 50 MW. Despite the prevalence of solar EPC companies, some even supported by major business groups like Beaconhouse, only 27 solar IPP licences have ever been requested, with a mere 12 being granted. It’s an exclusive club, one that the Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh plant would grant access to if a bid is ever made.

What happened at Kot Addu?

Now that we’re well versed in the requisite vernacular, let’s talk about the plant in question, and its inability to find a suitor. The RFP for the plant was floated in February with April being the deadline for the bids. This deadline was then extended to May, however, there were still no takers. The RFP was again floated in September with the project taken to Dubai as part of a roadshow in October — October 30 was the deadline for the bids as well. Again, no bids. Undeterred, the Private Power and Infrastructure Board (PPIB) has extended the deadline for bids to December 11.

Why does no one want this plant? The answer may be found in a low benchmark tariff, and ghosts of decisions past.

For starters, the initial RFP established a benchmark tariff that was too low for investors. A benchmark tariff, the price per kilowatt-hour (kWh) generated that the PPIB would have awarded any bidder for the duration of the PPA, represents the return any investor would have reaped from the project. This benchmark tariff was also unveiled at a reverse auction, and thus was the ceiling in terms of what could have been granted.

“One of the significant hurdles that the project developers encountered was that the benchmark tariff was unrealistic. At 3.4 cents, it was untenable,” explains Haneea Isaad, Energy Finance Specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

We talked to one potential investor who was contemplating making a bid for the project in the current round, as they believed that bids above the RFP would now be acceptable. Will they, or anyone else, submit a bid? It’s anyone’s guess.

Is the benchmark tariff the sole culprit? Not entirely. There is also the general risk premium associated with Pakistan. “We are a very precarious market compared to everyone else in our vicinity. From an investor’s perspective, looking at other comparable investment destinations such as India, Bangladesh or even Nepal and Sri Lanka, there is an added risk premium because of the state of our power market in terms of the circular debt and policy inconsistency,” explains Ali.

“It is a very challenging environment for investors, both internally and externally. Externally, there is a lot of political risk, whilst internally, IPPs have struggled to receive payments from the authorities,” Isaad continues.

Regarding the IPPs and their disputes with the authorities regarding payments, this is a recurrent phenomenon with IPPs frequently embroiled in tribunals, arbitration, and litigation against the authorities because they feel wronged. The Patrind Hydropower and Engro’s Powergen are just two notable examples. In terms of the delayed payments to the players in the energy sector, we’ve already covered the state of circular debt in 2023 previously.

Read more: Circular debt is at Rs 2.31 trillion. What does it mean?

The PPIB and the Government are in a bind. They cannot really entertain bids too high above their own benchmark tariff, assuming they did, because it would undermine the objective of the project: replacing costly fossil fuel energy with more affordable renewable energy. Similarly, the authorities are, well, the authorities, and they do have valid reasons at times for why they believe the IPPs might be inflating their costs.

Is there a solution to the entire matter? Yes. A very simple one at that too. Reduce the length of the PPA down from 25 years.

Killing two birds with one stone

The reality is, with solar, any benchmark tariff the Government dispenses will invariably gravitate towards the lower end. They may find themselves in the crosshairs of accusations of lowballing prospective investors, yet it’s not entirely their fault that solar tariffs have taken a nosedive over the years. This is simply the natural evolution of the technology.

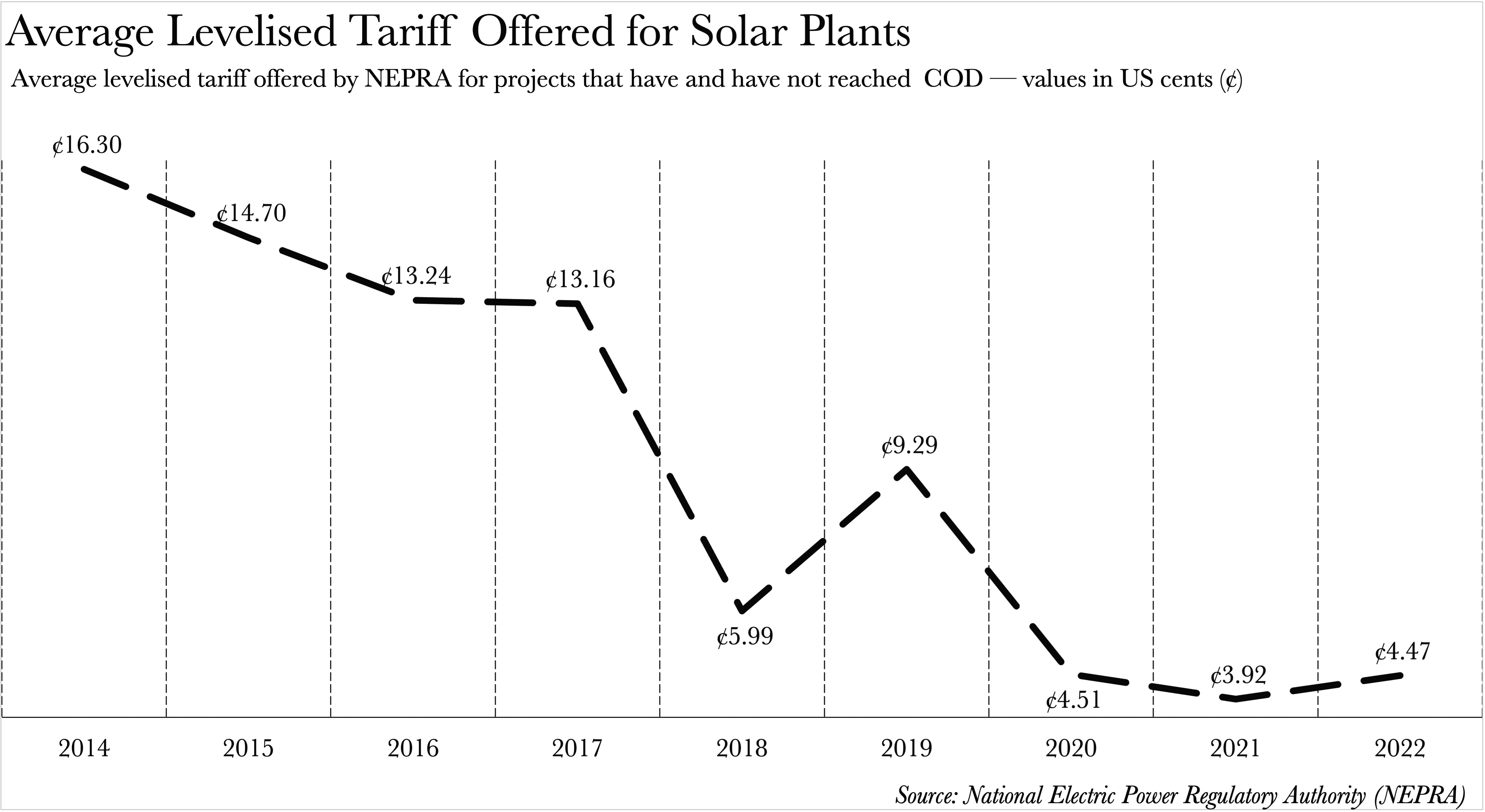

The average levelised tariff awarded by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) for solar power plants has plummeted from 16.3 cents in 2014 to a mere 4.47 cents in 2022. This represents a staggering 72% reduction in less than a decade. The decline in the cost to generate solar electricity is an inevitable consequence of technological advancement, rather than anyone’s fault.

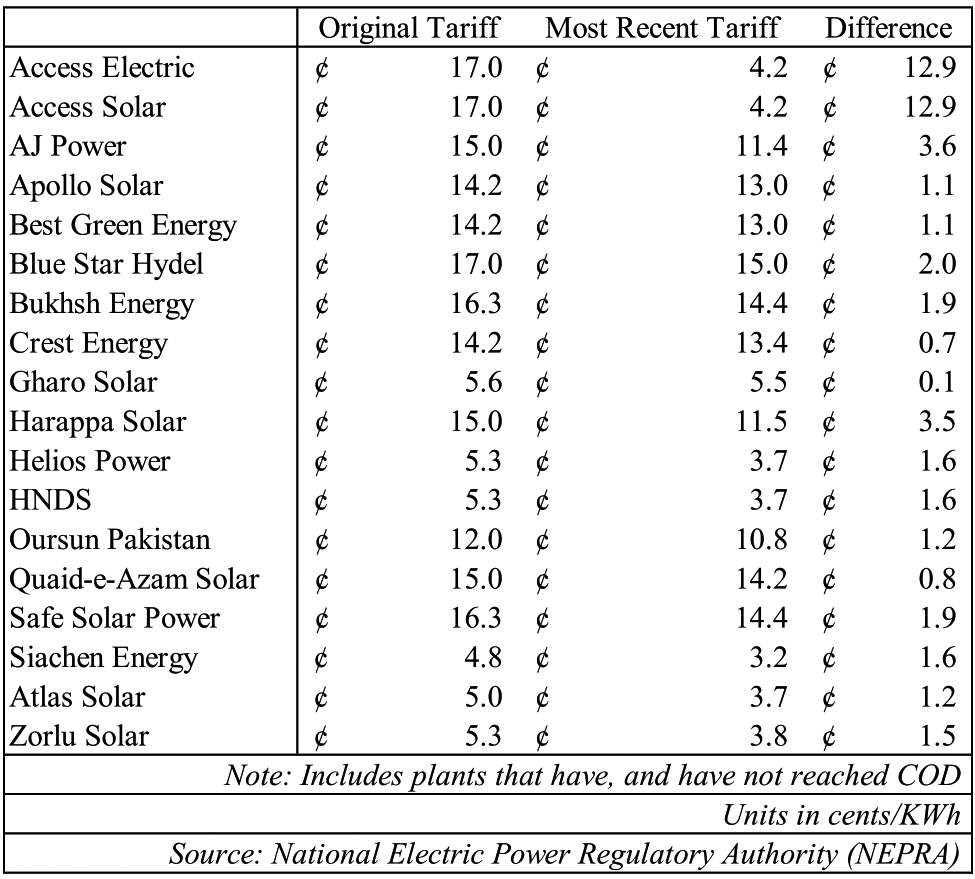

IEEFA estimates that the current tariff for solar has been benchmarked at 4 cents/KWh. Their estimation diverges from the average tariff handed out by NEPRA because they base their estimates on the recently operational Zorlu plant. NEPRA’s average tariffs for 2022 appear on the higher end because NEPRA had awarded tariffs to two other plants as well which originally accepted the exorbitant tariffs back in 2014 and then had their tariffs negotiated downwards until the plants came online. Remember how we mentioned the authorities have their reasons to be wary of Independent Power Producers (IPPs)?

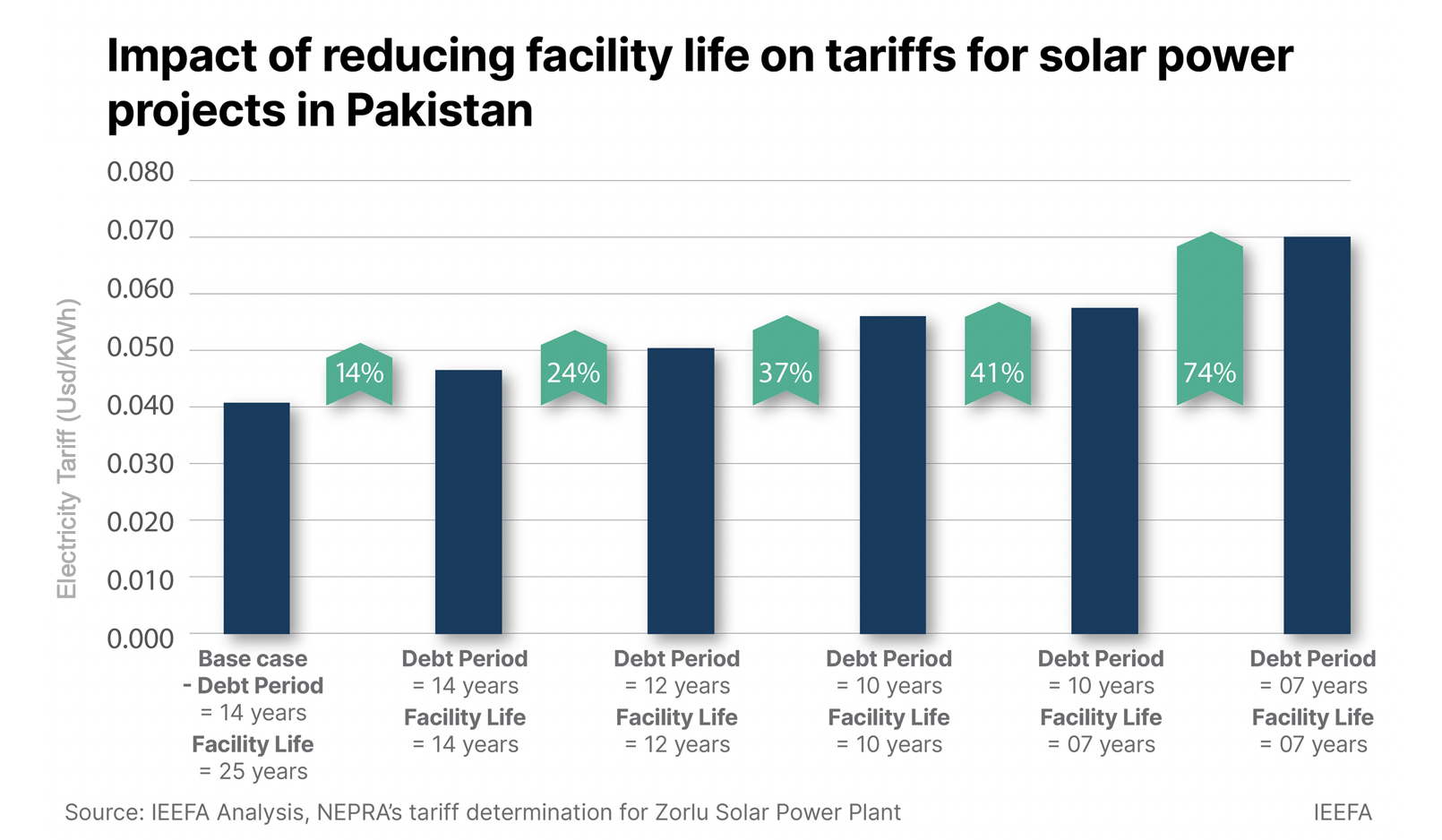

So, what does IEEFA’s 4 cents/KWh entail? Pakistan boasts one of the cheapest regional tariffs awarded to solar power, especially considering the limited capacity installed at present according to IEEFA. Combine this with the risk premium, and it becomes clear why investors might be tempted to look elsewhere in the vicinity. Reducing the length of the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) rather than just hiking up the tariffs for the sake of attracting investors provides a prudent solution that does not involve crippling capacity payments for decades to come.

IEEFA estimates that reducing the project term from 25 to 14 years would raise the benchmarked tariff, based on the Zolru plant, to 4.6 c/KWh, or a 14% increase. Reducing the PPA’s life to 12 years would increase it by 24%, to 10 years would increase the cost by 37%, and finally to 7 years would increase the cost by 74% to roughly 7 c/KWh. In contrast, some thermal power plants running on fuel oil or high-speed diesel now have fuel costs of 16-22 c/KWh, while fuel costs for imported coal and regasified liquefied natural gas are 9.5-13 c/KWh and 12 c/KWh respectively. Solar-based power generation would still be the cheapest form of power generation by a margin.

“A shorter contract term could lower risk for both the developer and the off-taker, especially as we consider the development of a secondary power market, post CTBCM, which the developer can sell to once the PPA with government ends,” asserts Isaad.

There’s also another advantage of reducing the PPA to as short as possible: not being stuck with outdated solar technology.

“Seven to ten years is a lot for the solar industry. Things change significantly in just a span of two to three years,” asserts Farheen Irfan, Chief Operating Officer at ACT Engineering Services. “We saw the industry move from the 300-watt series of solar panels to 400-watt to 550-watts in a matter of 2 years apart from one another. Experts predict the current prevailing P-type panels across the industry to become obsolete by December. By the time the Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh project comes online in 2024-25, we might well see the N-type panels ready to be replaced by the next generation of panels,” Irfan continues.

Could the choice between P-type and N-type panels significantly impact the performance of a solar plant? It’s a possibility. Solar panels, after all, have a theoretical efficiency limit of 30%. P-type panels achieve an efficiency of 23.6%, while their N-type counterparts reach up to 25.7%. Some argue that the solar industry has reached a plateau in terms of innovation. However, Irfan challenges this notion, asserting that “there is no immutable law stating that solar panels cannot surpass the 30% efficiency threshold should technology continue to evolve”.

What truly matters, though, is how these incremental efficiency improvements translate into tangible cost savings. “Advancements in solar panel technology have led to an average cost reduction of approximately 10%, while concurrently boosting the yield by 20% per technological iteration,” Irfan reveals. These efficiency strides are not exclusive to the realm of solar energy. A similar trend is evident in the wind industry. Wind turbines installed in 2014 boasted efficiency levels of 30%, whereas the latest models being deployed across the sector exhibit efficiency rates exceeding 45%.

Does it matter if we get this plant wrong? Is it that important?

The problem with not experimenting with Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh

In the grand tapestry of energy infrastructure, the Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh solar plant may seem like a mere stitch in Pakistan’s power grid. With a total installed capacity of 41,050MW, the 660 MW output of this plant is but a drop in the ocean. However, it’s not the size of the plant that matters, but its symbolic significance. This is the inaugural project under the Fast-Track Solar PV Initiatives 2022, and as such, it will set the precedent for future developments.

The looming spectre of lower tariffs in the future presents a tangible risk. A quarter of a century is a significant time span, and locking in rates now would mean cementing them for an entire generation. This is not to overlook the fact that Pakistan lacks both a competitive market and a proper wheeling market for electricity. In the current scenario, companies can only sell to the State of Pakistan, and with a capacity of 660MW, it’s improbable that any entity other than the State could absorb such a volume of energy. Unless the aforementioned issues are addressed, companies and the State will have to navigate within the confines of the status quo.

However, the status quo is proving to be an inadequate solution for what is poised to be the vanguard of Pakistan’s solar revolution. There’s a separate discourse to be had about the necessity of mega projects of this scale for solar energy, but the Government and PPIB’s unwavering commitment suggests that this project is likely to materialise. The only question that remains is whether Pakistan is willing to experiment with its energy infrastructure and agreements, now that it has the opportunity to do so.

another dollar index contract made to bleed Pakistanis… just pay good rupee return to rooftop solar owners.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Great timing blogs

Wonderful article. I am in this industry for last 20 years. if anyone wants to understand power sector and its core issues then its a must read article.

Pakistan’s government bungled the sale of the Kot Addu-Muzaffargarh solar plant, making it unattractive to potential investors.

Despite being a coveted asset, the mishandled bidding process has deterred interest, leaving the government holding onto a valuable opportunity.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Hey what a brilliant post I have come across and believe me I have been searching out for this similar kind of post for past a week and hardly came across this. Thank you very much and will look for more postings from you.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

SAP IBP training covers concepts from the Basic level to the advanced level. Whether you are an individual or corporate client we can customize training course content as per your requirement. And can arrange this SAP IBP training at your pace.

Hey what a brilliant post I have come across and believe me I have been searching out for this similar kind of post for past a week and hardly came across this. Thank you very much and will look for more postings from you.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Thanks for the valuable information and insights you have so provided here…

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

I like this content.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Love to read it,Waiting For More new Update and I Already Read your Recent Post its Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.v

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Thanks for the valuable information and insights you have so provided here…

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

Thanks For sharing this Superb article.I use this Article to show my assignment in college.it is useful For me Great Work.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

It was wondering if I could use this write-up on my other website, I will link it back to your website though.Great Thanks.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

What a fantabulous post this has been. Never seen this kind of useful post. I am grateful to you and expect more number of posts like these. Thank you very much.

Wow what a Great Information about World Day its very nice informative post. thanks for the post.