They say there is a great big lever that exists somewhere in the building of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). While the central bank performs countless functions from granting approvals to regulating the financial sector, its most prominent and closely watched responsibility is this lever.

The SBP’s governor is the custodian of this lever and pulls it either way with the help of his Monetary Policy Committee. The lever either increases or decreases the rate of interest in the country. Now, Profit’s more discerning readers might have picked up on the fact that this publication has been more critical than usual of the state bank’s use of this lever. It seems to us that the SBP has adopted a reactive monetary approach, resulting in inflation peaking at around 30% last year and still exceeding 20%.

This has been going on since at least 2021. At first, it even seemed prudent as a measure to curb inflation. But it now seems almost rehearsed and as a result predictable. It seems that the SBP has decided to be quite reactionary in their pulling of the lever. The problem with this is that a lot hinges on which direction the lever moves. Already the persistent increases in the policy rate have inflicted significant damage on the corporate sector and consumer purchasing power during this period.

Another consequence of the policy directives in recent years is a notable shift in the business strategies of companies, particularly in the financial sector.

The publication has already discussed how commercial banks have shifted away from traditional banking practices towards becoming investment firms. That is, banks have been prioritising investment in secure government securities, over riskier private sector lending.

Surprisingly, we have also observed a similar trend in a sector that bears the responsibility of serving segments overlooked by commercial banks.

We are referring to the Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), a sector that states its primary objective as contributing to capital formation and economic development in the country by providing long-term financing.

However, over the past year and a half, the majority of players in the sector have adopted a strategy that resembles a leveraged fixed-income fund rather than a DFI.

What has contributed to this shift? Let’s delve deeper and explore.

State of play

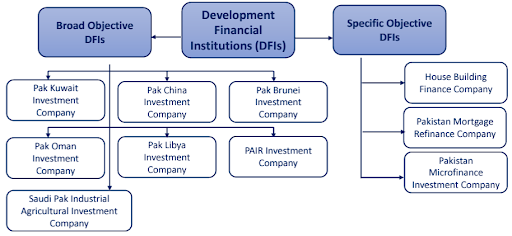

Presently, there are two categories of DFIs operating in Pakistan: broad objective DFIs and specific objectives DFIs. Broad objective DFIs are also known as joint venture financial institutions. They have been established in cooperation with bilateral partners and are majority-owned by national governments to implement the government’s foreign development policies.

The shareholding structure of joint venture DFIs consists of 50% ownership by the Government of Pakistan, through either the Ministry of Finance or State Bank of Pakistan. The remaining 50% is owned by the respective foreign governments through relevant institutions.

On the other hand, specific objective DFIs are created for the development of a specific sector. Their ownership structures are more varied, with shareholding held by national and international financial and developmental institutions.

(Note: we will focus on joint venture DFIs in this story)

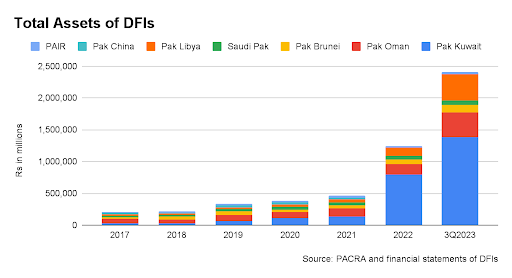

In Pakistan, there are seven joint venture DFIs: Pak Kuwait Investment Company (PKIC), Pak China Investment Company, Pak Brunei Investment Company, Pak Oman Investment Company, Pak Libya Investment Company, PAIR (Pakistan-Iran) Investment Company and Saudi Pak Industrial Agricultural Investment Company. With an asset base of Rs 1.4 trillion, PKIC is the largest DFI in Pakistan. Pak Libya and Pak Oman follow with an asset base of around Rs 412 billion, and Rs 389 billion respectively.

“All DFIs are relatively small except for PKIC. PKIC’s advantage lies in its 30% stake in Meezan Bank, from which it receives dividends of around Rs 12-13 billion. Hence, PKIC’s profitability compared to other industry players will be significantly different due to these high dividends,” explained an industry source.

The change in fortunes

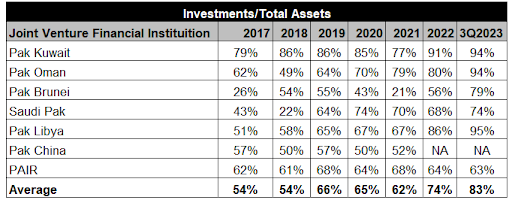

The sector has historically managed to grow its asset base steadily with investments dominating the asset mix followed by advances. The latter averaged around less than half of the investments over the years.

However, since 2022, there has been a meteoric rise in this trend. “The share of investments in the total asset base has grown steadily over the years (2017-2022), and clocked in at 74% in 2022, up from 54% from 2017-18 and 62% the previous year. This was spurred by the increase in investments in government securities, which occupy the largest share in investments,” read a sector study by PACRA.

“The average share of the segment’s federal investments in their total investments portfolio stood at 73.8% in 2022 (2021: 62%). In absolute terms, the segment’s total investments in federal securities clocked in at Rs 881 billion in 2022, 6 times the levels in 2021, when they had amounted to Rs 155 billion. The share of investments in total assets of the segment rose to further 77% during the first quarter of 2023,” it added.

The figures above illustrate a growth of over 600% in the asset base in less than two years, driven by investments in government securities. If this seems familiar, you’re not alone. We have traversed a similar path before, albeit in a different sector.

Read: Has UBL paved the way for other banks to maximize arbitrage opportunities?

Raising eye-‘borrows’

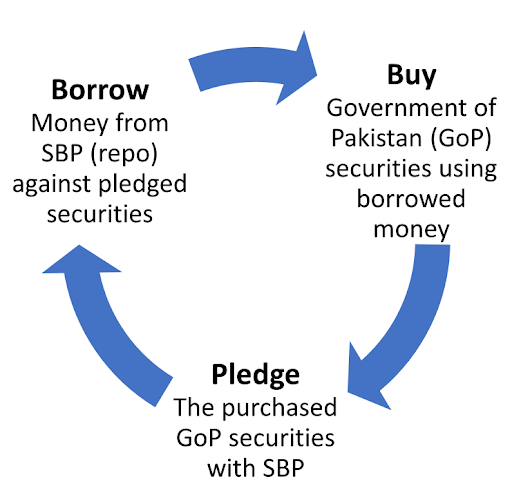

The sector’s investment surge was fueled by the good old repo borrowings. Similar to commercial banks, DFIs borrowed from the SBP using government securities as collateral to fund additional government securities purchases. These securities, in turn, act as collateral for more borrowing, thus perpetuating the cycle.

However, unlike banks, DFIs have only recently gained the privilege to conduct transactions in this manner and scale. In June 2022, the SBP allowed all DFIs to participate in Open Market Operations (OMOs) to facilitate DFIs in their “liquidity management”.

Profit has already covered what OMOs are previously. It is a tool used by the central bank to control liquidity in the interbank market by buying and selling government securities. OMOs usually take two forms: mop-ups and injections. In an injection, also called a repo, the SBP lends money to banks in exchange for securities. While in mop-up, also called reverse repo, the SBP borrows money from banks in exchange for securities.

Read: The Who, What, Where and Whys of OMOs

In this context, the SBP has injected money: it has lent money to DFIs in exchange for government securities and DFIs have used these repo borrowings by investing in more government securities.

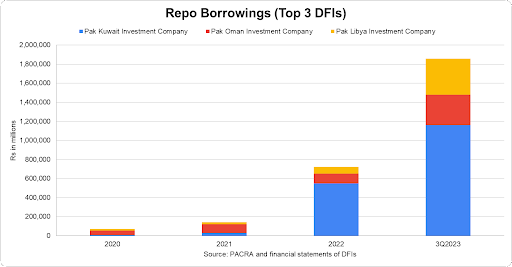

Note: Prior to June 2022, repo borrowings constitute of banking market transactions

The top 3 DFIs that have the sector’s majority exposure to these transactions have now resorted to earning spreads available between borrowings from SBP versus investing in government papers.

As per a note in PKIC’s financial statements for the third quarter of 2023, “The Company has arranged borrowing from financial institutions against sale and repurchase of government securities. The mark-up rates on these borrowings are between 21.50% and 22.15% per annum (December 31, 2022: 15.22% and 16.21% per annum) with maturities between two days to fifty five days (December 31, 2022: sixty three to seventy days).”

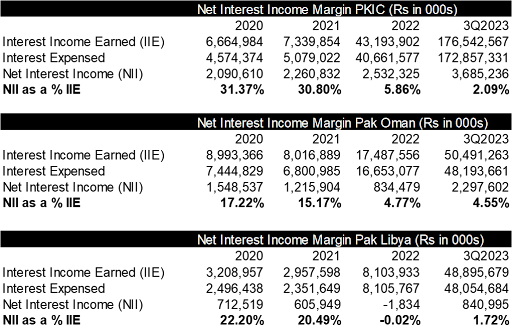

Consequently, the borrowing rate is exceptionally high and nearly equals the returns on government securities. This results in narrow margins, making it essential to focus on volume to enhance profitability.

The DFIs have followed this strategy religiously. The quantum of repo borrowings, particularly among the industry leaders, is substantial. The top 3 players have accumulated borrowings of approximately Rs 1.8 trillion by the third quarter of 2023. During the same period, the outstanding OMO positions by the SBP stood at around Rs 5.9 trillion. This means that almost 30% of outstanding positions were parked with these three entities with the majority being held by PKIC.

This might immediately raise concerns over the possible liquidity implications of such a highly leveraged strategy. However, as per SBP’s financial stability review for 2022, “Maturity-wise breakup reveals that a major part of assets and liabilities have shorter maturity of within one year. The maturity mismatch in this time bucket slightly increased over the year to 22.5 percent of total assets (from 20 percent in CY21) as the sector heavily relied on short-term borrowing to finance the asset base. However, ample availability of liquidity cushion in the form of low-risk assets abated the concerns of maturity mismatch, as the share of liquid assets in total assets increased significantly to 77.9 percent (54.7 percent in CY21). Furthermore, liquid assets to short-term liabilities ratio largely remained stable at 98.2 percent.”

While this strategy has transpired into healthy profitability growth for the sector as the volume play yielded dividends, it comes at the expense of DFIs neglecting their primary objective – serving as enablers of development finance.

One might expect regulatory intervention, but in this instance, the central bank is actually one of the primary enablers of the trend. By simply issuing the circular mentioned earlier in this story, the SBP created another avenue for lending to the government to meet the federation’s perpetual need for deficit financing.

The flip side

It is important to consider why DFIs felt compelled to engage in this mechanism. These institutions rely solely on term deposits and investment certificates as sources of funding, which is not adequate. Thus, they depend on borrowings and their own equity for financing.

“We borrow from commercial banks and then we lend to the same clientele that already has access to commercial banks. In other words, we are competing against commercial banks after borrowing from the same commercial banks. We can’t compete. Our cost of funding will definitely be higher. Commercial banks lend to us at Kibor plus some spread. So we will be lending at costly rates for commercial borrowers. Long-term financing at 25-26% interest rates in unviable,” lamented a CEO of one of the DFIs.

Hence, the biggest challenge faced by DFIs is the lack of cheap sources of funding. “DFIs around the world receive funding from their governments, which is not the case here”, remarked a CEO of a DFI.

Securing funding from international sources presents another challenge due to Pakistan’s elevated country risk. International funding typically involves receipts in dollars, necessitating dollar repayment.

Over the past 1.5 years, Pakistan has experienced significant liquidity issues, with foreign exchange reserves decreasing to approximately $4.5 billion in June 2023, barely sufficient to cover a month’s worth of imports. To address dwindling reserves, the SBP implemented restrictions to manage foreign exchange outflows. As a result, Pakistani corporations were unable to repatriate dividends to their overseas parent companies, undermining investor confidence.

“The OMO facility can facilitate the day-to-day asset-liability management of DFIs as they face quite constrained funding sources due to limited mandate on deposit mobilization, limited outreach of the capital market, and low savings rates in the country. These factors, along with other structural issues, are the leading reason behind DFIs’ inability to perform their primary objective i.e. to contribute in the capital formation and economic development of the country by extending long-term financing. Accordingly, the DFIs in general focus on investment in securities, interbank and capital market activities, and limited financing business, while equity and borrowings remain the mainstay of funding,” read the State Bank’s financial stability review for 2022.

Similarly, the support of SBP is also crucial. “SBP does not support DFIs the way they should be,” lamented an industry source. “For example, TERF should have been pushed through DFIs because long-term financing is much more riskier. However, DFIs got a negligible share. Our allocations were rejected despite being strong in capitalisation ”, a source from one of the leading DFIs expounded.

TERF — which stands for Temporary Economic Relief Facility — was launched in 2020 during the peak COVID-19 pandemic. It was essentially a facility launched by the SBP with the help of the government that provided nearly interest-free loans to businesses so they could keep the wheels turning and not lay off their employees. Over time, more than 600 businesses took advantage of this facility and the SBP lent over $3 billion for this purpose.

Despite the lack of external support, DFIs still possess the capability to take the initiative. The key lies not in focusing on what is lacking, but in maximizing the potential of existing resources: DFIs are backed by sovereign entities, and if effectively promoted, this support can be leveraged to raise funds at favourable rates.

Well an amazing article on this subject.