The strategy from Pakistan’s banking sector has been pretty clear over the last couple of years. As the economy has gone through the process of overheating during dangerous political turmoil and the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has maintained consistently high interest rates due to inflation, commercial banks have taken the easy approach to surviving and thriving.

A bank’s business is to accept deposits from customers and lend it to other customers. It’s a pretty basic model at the heart of it. But with inflation hitting record highs and interest rates still capped at 22%, businesses haven’t exactly been lining up for credit. So what do the banks do? They lend to the one entity that does constantly need money no matter what: the government.

By lending with minimal risk and earning a favourable spread between borrowing and investment rates, banks have achieved impressive profits in hard economic conditions. Commercial banks posted an impressive 83 percent earnings growth during 2023, with almost all banks recording historic profits.

The allure of these rich rewards have been the subject of discussion within the country’s financial circles. Economists have been concerned that while unprecedented interest rates yielded higher profits for banks, they were overburdening the economy because of costly borrowing. Private businesses have made similar complaints. Interestingly enough, however, there are those within the banking sector as well who are concerned by the current predicament.

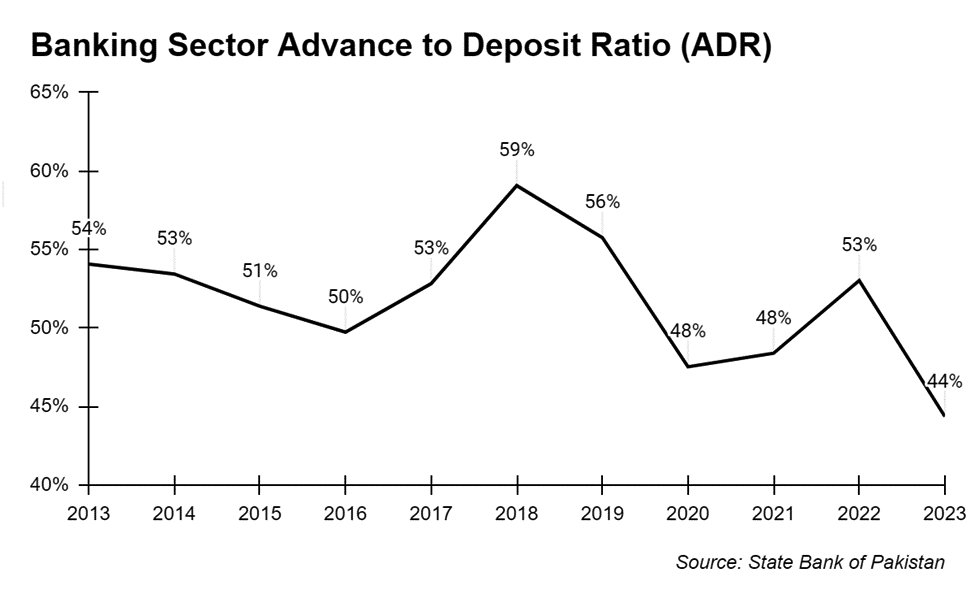

Lending to the government is profitable at a time like this. But it severely impacts private sector credit. The inherent risks associated with engaging in lending operations, particularly in the current high-risk environment, have also constrained the growth of the banking sector’s credit portfolio.This is reflected in a low Advances-to-Deposit Ratio (ADR) of only 44% as of the end of 2023. This means Pakistan’s banks lent Rs 0.44 for every rupee they received from their depositors in 2023, reflecting a poor state of affairs in private credit.

But this is also the conundrum part of the equation. You see, banks do want to lend to the private sector. Why would they not? They can make money from the government too but private credit is a lifeline. The problem is that some borrowers in particular are fast becoming very high risk. Take, for example, the textile sector. Their business has plummeted because of the ongoing economic crisis. In such a scenario, will they make good on their loans or could lending more give banks a lot of non-performing loans on their books? After all, this also wouldn’t be the first time the textile industry gives commercial banks a big hit. Profit investigates.

Not the first time

The year is 2005. Pakistan’s textile industry is thriving. It is one of the largest textile operations in the world. Thanks to the textile industry, cotton farmers in the country are also thriving and the production for that year was 15 million bales. Similarly, banks are having a field day lending to what has become a reliable sector of the economy.

And then the energy crisis hit. From 2005 onwards Pakistan had a dire lack of electricity both for domestic and commercial consumers. The machines could no longer run and over the next 10 years over 10% of mills in the country would shut down. In fact, here is a sobering statistic. Two decades ago Pakistani textiles were in demand globally. However over those 20 years, countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have all surpassed Pakistan. In 2003, when Pakistan’s textile exports were $8.3 billion, Vietnam’s textile exports were $3.87 billion, Bangladesh’s were at $5.5 billion. Now Vietnam is at $36.68 billion and Bangladesh is at $40.96 billion, while Pakistan is struggling to hit $20 billion in 2022.

The fall of the textile sector has sent ripples throughout the economy. Our exports have teetered, cotton has been decimated as a crop, and back in the aftermath of the energy crisis Pakistan’s banking sector was also facing a reckoning.

Because the industry was so massive, when mills started defaulting on loans the banking sector was suddenly facing a crisis. Around the peak of the crisis in 2008-09, the government had to step in and try to mend relations and negotiate a solution. A one year moratorium was given by the State Bank of Pakistan, while restructuring of outstanding loans and interest rates were to be settled with commercial banks for which multiple committees were being formed.

Perhaps nothing covers the dire atmosphere better than this Dawn article from 2009:

“Yet another committee is being formed by the government to bring depressed and demoralised textile tycoons and concerned and worried bankers on one forum to discuss repayment schedule of outstanding loans, interest rate and other related issues.”

Dejavu?

For a while, the banking sector learned from its mistakes. But around 2020, things were picking up for the textile industry once again. There was a significant increase in textiles and apparel exports from 2020 to 2022, growing by 54%. The industry experienced a decline in exports to $16.5 billion in 2023, down from $19.3 billion the previous year, attributed to the economic crisis and the removal of export facilitation measures.

But this was a small blip. The textile industry has encountered various challenges in recent years. The sector is currently struggling to return to its pre-crisis export levels, facing obstacles such as uncompetitive energy prices, liquidity shortages, and delays in tax refunds. Limited investment in manufacturing capacity has also hindered export growth, with the sector’s annual export capacity estimated at around $25 billion.

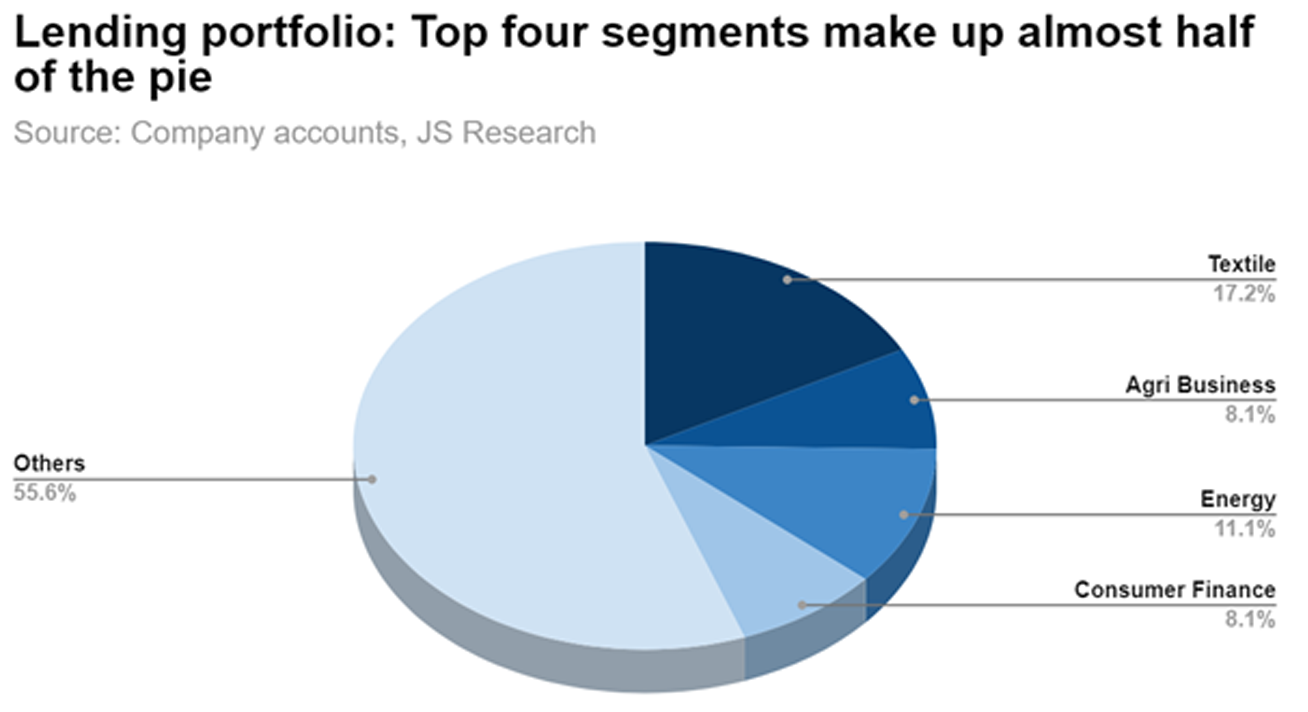

The textile sector’s health, in particular, is a significant concern for many banks due to their considerable exposure to businesses in the industry.

“Any downturn in the textile industry could lead to a surge in Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) for banks, as the textile sector constitutes a significant portion of banks’ credit loan books, its instability poses a substantial threat to the overall financial health of the banking sector directly affecting their profitability,” remarked Saad Hanif, deputy head of research at Ismail Iqbal Securities.

“With many textile companies heavily reliant on bank financing for working capital and expansion, adverse market conditions, such as fluctuating cotton prices, energy shortages, or global demand shifts, can strain their ability to service debts, thus increasing default risks. Moreover, the interconnectedness of the textile sector with various ancillary industries amplifies the ripple effects of any downturn, potentially worsening asset quality across the banking sector.”

Banks on the receiving end

Let us for a second step away from textiles and look at what the banking sector has been doing recently. Over the past decade, Pakistani banks have experienced a significant transformation in the delivery of services and the range of products offered to customers. The introduction of digital banking services stands out as a notable example.

Given the advancements in technology, one might expect a corresponding evolution in the lending profile, with a larger portion of the portfolio directed towards the private sector. However, this expectation has not materialised. In fact, the situation has taken a turn for the worse.

Since 2013, the ADR has consistently remained above 50% with the exception of three years and reached its highest point in 2018 at around 59%. However, it currently stands at an all time low of 44%. Notably, the years in which the ratio fell below 50% were 2020, 2021, and, obviously, 2023. The downward trend in the ADR would likely have persisted in 2022 if the government had not opted to penalise banks with ratios below 50% by imposing additional taxation.

The current macroeconomic headwinds make it extremely difficult to maintain the quality of the loan book especially after the prolonged monetary tightening cycle.

“A monetary tightening cycle generally invites concerns over asset quality of banks and potentially large provisioning expenses. This cycle, which has witnessed a 1,500 bp expansion in Policy Rate (22%) in the past 3 years, is no different when it comes to similar concerns,” writes Amreen Soorani, head of research at JS Global Capital, in an analyst note.

“Moreover, in midst of these concerns, the sector faced regulations discouraging a lower ADR by penalising the same via higher taxes, which were later exempted for the year 2023, but currently remain in place for 2024 and beyond. This exemption for 2023 led to banks moving away from loan disbursements this year, reducing ADR from 53% to 44%, as lending demand also reduced amid higher borrowing cost, coupled with the banking sector cherry picking blue-chip borrowers to shield its asset quality,” she adds.

The concerns raised by Soorani in her analysis have also been echoed by Pakistani businesses. Recent reports indicate that corporate clients of commercial banks are feeling the effects of the record-high policy rate.

Key sectors affected include textiles (specially spinning and weaving), steel rebar manufacturers, and poultry feed mills. These sectors are not only grappling with high financing costs but also contending with the impact of demand-suppression measures which have significantly impacted their revenues.

While the repercussions of declining asset quality may pose a threat to banking profitability, institutions have implemented certain safeguards to prevent a sudden increase in loan losses on their books. The primary measure involves recording timely provisions for indicative asset quality deterioration.

While the repercussions of declining asset quality may pose a threat to banking profitability, institutions have implemented certain safeguards to prevent a sudden increase in loan losses on their books. The primary measure involves recording timely provisions for indicative asset quality deterioration.

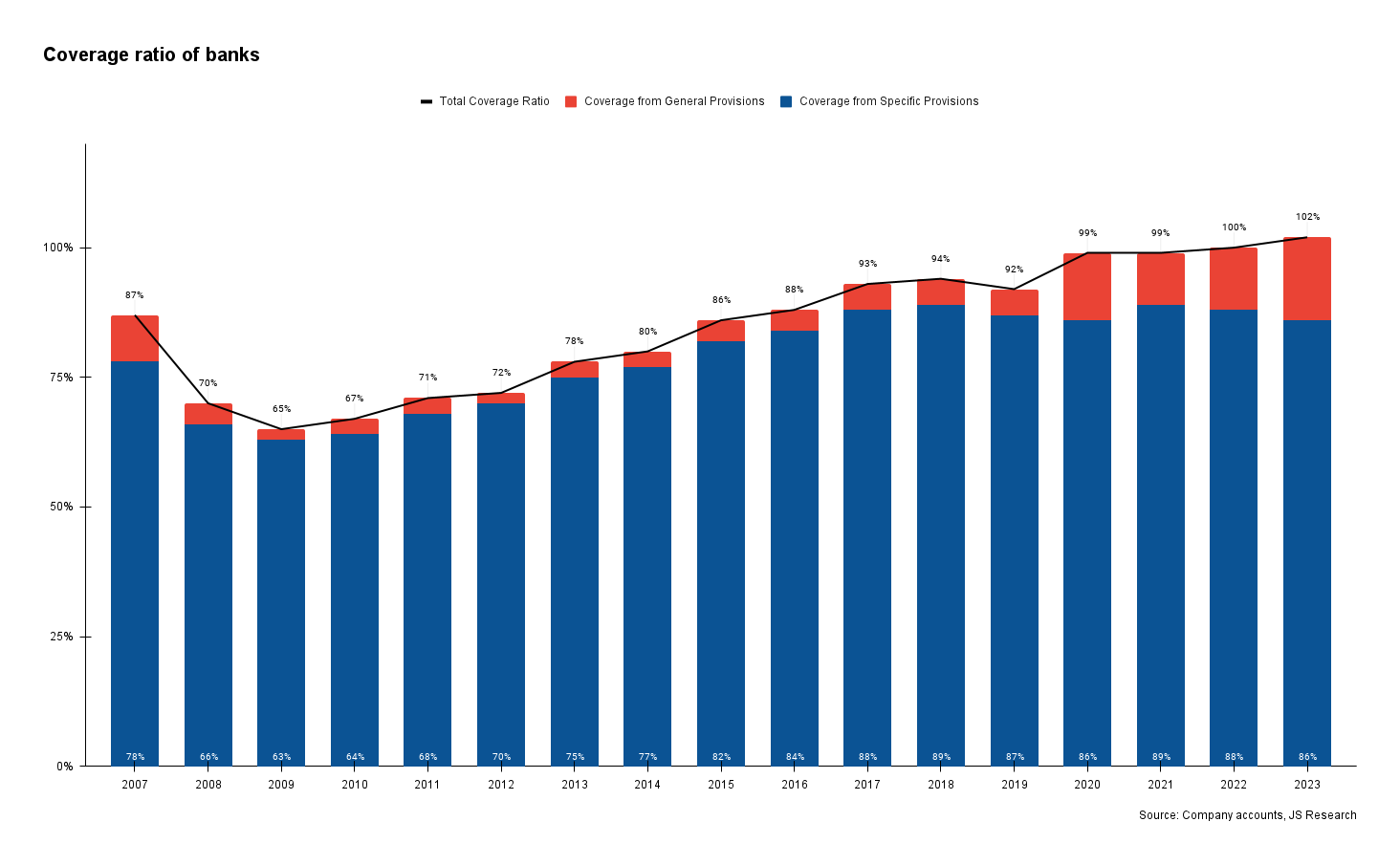

How well the banks are shielded in case of an adverse event can be gauged through the coverage ratio, a measure of the adequacy of a bank’s provision reserves relative to its NPLs, calculated by dividing reserves by NPLs. A higher ratio means better coverage for potential losses.

While the cumulative coverage ratio exceeds 100% for major banks in the sector, the results are skewed due to some outliers as pointed out by Soorani in her analysis. “Among our banking universe, while Coverage Ratios for only half of the banks surpass the 100% mark, the sample average also went beyond 100% this year, skewed by Meezan Bank’s 179% Coverage ratio. Banks further expanded coverage though General provisioning this year, with a growth of 40% YoY. Overall coverage under General provisions clocked in at 15%, with 86% covered through Specific provisions.”

While the cumulative coverage ratio exceeds 100% for major banks in the sector, the results are skewed due to some outliers as pointed out by Soorani in her analysis. “Among our banking universe, while Coverage Ratios for only half of the banks surpass the 100% mark, the sample average also went beyond 100% this year, skewed by Meezan Bank’s 179% Coverage ratio. Banks further expanded coverage though General provisioning this year, with a growth of 40% YoY. Overall coverage under General provisions clocked in at 15%, with 86% covered through Specific provisions.”

However, that’s not all there is to it. The decline in the sector’s asset quality coincides with the implementation of IFRS-9 by Pakistani banks, potentially resulting in the recognition of accelerated provision losses by these institutions.

The IFRS-9 Conundrum

Before delving deeper, it is important to understand a few financial jargons. First is the application of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These, as the name suggests, are global standards that set the rules for drafting financial statements. The standards are adopted by many countries including Pakistan, to ensure the uniformity of financial reporting to allow for comparability of financial statements and investor reliance.

Now the specific standard under question is the IFRS-9. The standard essentially governs the treatment of financial instruments including assets and liabilities.

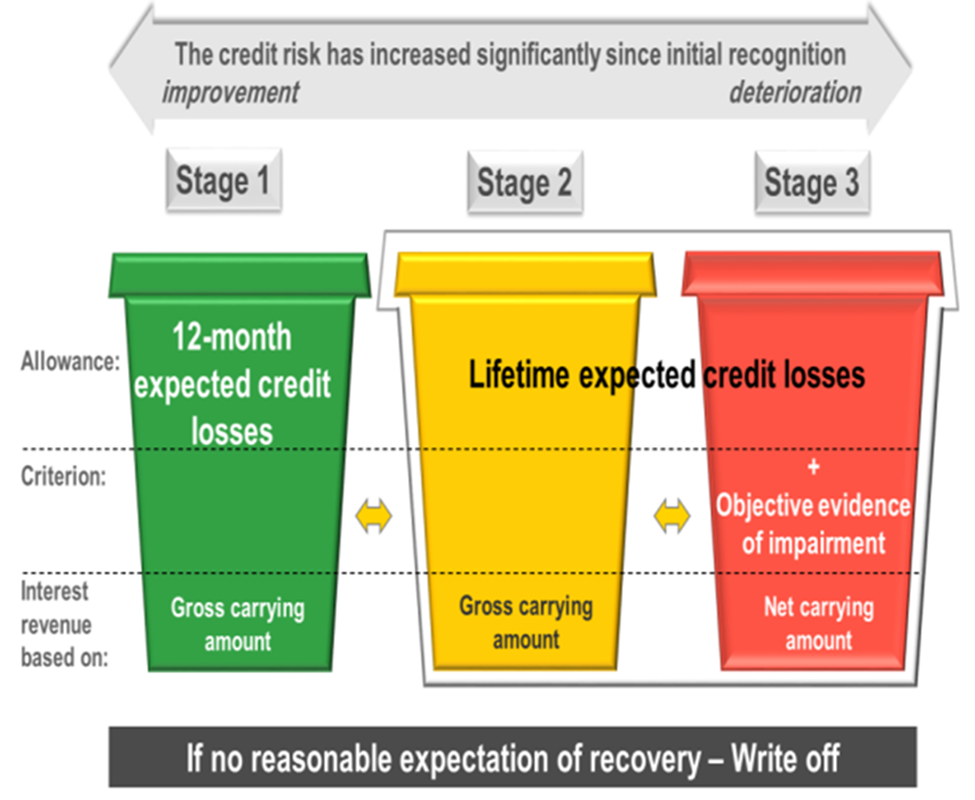

For the purpose of this story, we will be explaining a certain section of that standard which is the Expected Credit Loss (ECL) Model and its impact on the loan portfolio. The standard, under the ECL Model, requires that the outstanding loan portfolio should be assessed periodically, and an expectation must be developed of its recoverability. If a portion of it is deemed unrecoverable, an appropriate provision should be recorded or in simple terms a loss should be booked.The quantum of the loss depends on the stage of the assessed credit risk. So, initially the loans are placed under stage 1 which doesn’t imply a significant risk of default. However, if there is a significant increase in credit risk like amounts being rescheduled or categorised as NPL, the loans are moved to stage two and three, and additional amounts are provided for.

As per Hanif, “under IFRS 9, banks are required to assess the credit risk of sectors they have exposure to, considering various factors i.e. macroeconomic conditions, industry trends, and specific sectoral risks. In the case of Pakistan, where macroeconomic conditions and economic headwinds have posed challenges to multiple sectors, it is likely that several sectors would fall into higher-risk buckets under IFRS 9.”

As per Hanif, “under IFRS 9, banks are required to assess the credit risk of sectors they have exposure to, considering various factors i.e. macroeconomic conditions, industry trends, and specific sectoral risks. In the case of Pakistan, where macroeconomic conditions and economic headwinds have posed challenges to multiple sectors, it is likely that several sectors would fall into higher-risk buckets under IFRS 9.”

This implies that banks would need to evaluate and assign ratings to sectors and obligors individually, which would then form the basis of their provisioning assessment.

The outlook

As per BMI Research, the research arm of Fitch Solutions, which is also the parent company of Fitch Credit Ratings, in 2024 stronger economic growth and improved business sentiment are expected to drive private sector loan growth in Pakistan, particularly in the manufacturing sector. Despite a decline in manufacturing loans in 2023 due to challenges in textiles and chemicals, the rebound in agricultural and industrial output is anticipated to positively impact manufacturing subsectors such as food products and textiles in the upcoming quarters, leading to a rise in manufacturing lending in 2024.

However, securing additional funding from the IMF by increasing tax revenue may pose risks to business reinvestment rates, household purchasing power, and subsequent credit demand, potentially limiting client loan growth compared to historical trends.

Moreover, a lot depends on the revival of demand for key products in sectors such as textiles and the initiation of a monetary easing cycle to alleviate financial cost pressures for private businesses, thereby enhancing their debt servicing capacity.

Very important issue described with deep thinking. Being part of textile sector I can understand topic, this text really shows very keen research. Thanks.

banks should be restricted to play treasurey bills and 70%of thier business should go towards sme and industrial sector otherwise Economic cycle will collapse and so does GDP growth…so act now sir minister Aurangzeb as u know very well what banks r playing around

A very well-researched article! This is the kind of journalism and analysis we need. Keep it up Profit

Nothing wrong from Banking perspective, its high cost of funds(too high KIBOR) which is practically un-workable & un-payable under present economic conditions and level of large/small business activity.

There is no as such “high inflation” rather its totally mis-managed supply side of general items from where “Inflation Number” ot CPI is calculated……Cost of funds must be brought down in single digit to make run the wheel both for large & small sector manufacturing

HOW I FINALLY RECOVERED MY LOST BITCOIN:

Do you need help on how to recover lost or stolen Bitcoin from fake investment scammers? I lost all my Bitcoin to a fake investment scam to someone I met online. After losing my Bitcoin investments, I was determined to find a solution. I started searching for help legally to recover my funds, and I came across a lot of Testimonies about GEO COORDINATES HACKER. I am incredibly grateful for the exceptional service, and wanted to inform you all about this positive outcome. They emphasized their excellent strategy for Bitcoin recovery. In order to assist people and companies in recovering their lost or stolen cryptocurrencies. They guarantee that misplaced bitcoins have an opportunity to be recovered with their excellent services. If you or anyone you know ever finds yourselves in a similar unfortunate situation, I highly recommend reaching out to GEO COORDINATES HACKER. Contact Info Email:

( [email protected] )

Email; ( [email protected] )Telegram ( @Geocoordinateshacker )Website; https://geovcoordinateshac.wixsite.com/geo-coordinates-hack

Its so fantastic work.