In the most literal sense of the word, PIA is worthless.

In fact, it is worse than worthless because even if it is given away for a price of Rs0, the buyer would become poorer, not richer, because they would now own the responsibility to pay back the airline’s debts, which far exceed its ability to pay them.

So how do you find a buyer for something that is worse than worthless? It is a long and complicated process, but you start by accepting the fact that the transaction is going to lose you money.

And when it is a private sector company, you then begin a process of distributing the pain among the owners (shareholders) and the lenders into the company, a process where the amount of pain you will feel is directly proportional to how much risk you accepted when you gave the company money. The lenders, who accepted a fixed, lower return generally expect the lowest losses and expect to be paid back first. Shareholders, who had accepted higher risk, expect the highest losses, and in the event of bankruptcy generally do not get paid back at all.

But when an entity is a state-owned company – and an economically important one such as the national airline – the rules are not strictly what is dictated by corporate and bankruptcy law. The government is a more powerful borrower than just about any other borrower, but its powers are also not limitless. Who comes out on top in a negotiation between the government and a consortium of virtually every single bank in the country is a question without an obvious answer.

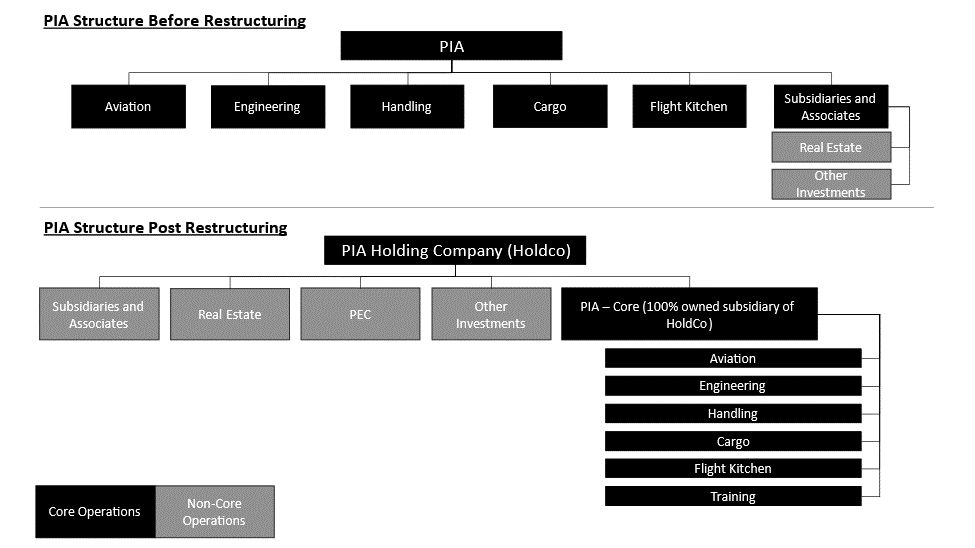

The deal struck between the government and the banks on restructuring the debt of the state-owned Pakistan International Airlines, offers us some clues as to what the answer might be. Somewhat surprisingly, given the general incompetence of the government of Pakistan on all matters of economic policy, the government ended up with an agreement where it neither strong-armed the banks into accepting heavy losses, nor did it completely cave and let them have everything and absorbed all the losses.

Source: JS Global Capital Limited

It achieved, in other words, what one would expect from a negotiation between relatively evenly matched parties: a balanced deal.

How did that happen? To answer that, it helps to understand the context of what the government is trying to achieve, what it offered the banks, and why it got the best of what was not an obviously strong negotiating position. The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan