Bank Alfalah has pledged Rs 1.4 billion ($5 million) to support communities devastated by this year’s monsoon floods. On the surface, this may seem like basic CSR spending. The floods, after all, were the biggest feature in the news cycle this year and it makes sense for an organisation to spend CSR money on rehabilitating communities that suffered losses during the unprecedented rains.

But scratch beneath the surface and there is more than meets the eye. The recent contribution of Rs 1.4 billion has now taken Bank Alfalah’s cumulative contributions for flood-related relief to a total of $15 million since 2022 when the last mega floods hit Pakistan. The amount of money announced in social welfare by Alfalah is unprecedented, not just in absolute terms but also as a percentage of its profit.

So why invest so heavily in this one area? Behind the decision are a number of factors. There is, of course, the desire to help a sector that has traditionally been unattended by banks and financial institutions during a time when it is struggling from natural calamities. Agriculture has traditionally been underserved by Pakistan’s banks and at a time when banks are taking more of an interest in it, the sector faces its greatest threat: climate change.

In a press briefing in Lahore, Bank Alfalah’s President & CEO Atif Bajwa described the pledge as “a commitment to rebuilding lives and strengthening climate resilience”. He said the funds will be deployed across housing reconstruction, education, health services and climate-smart agriculture through partnerships with over 25 organisations including the Aga Khan Development Network, the Citizens Foundation and the Karachi Relief Trust.

But one question remains: how is the banking industry responding to the floods, and how much of a difference will their CSR approach make?

CSR and Pakistani Banks

The notion that good intentions can be organized, institutionalized, and scaled through corporate systems is not new. Over the years, this idea has found its corporate manifestation in what the business world calls Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR); a company’s voluntary commitment to improving society beyond its bottom line.

In boardrooms and annual reports, CSR sits comfortably beside profitability metrics and mission statements. It promises that capitalism, if done thoughtfully, can serve not only shareholders but society at large. Yet, for all its appeal, CSR remains a contested idea. Is it genuine compassion or just a new language of self-promotion?

These questions take on new meaning in Pakistan, a country frequently tested by climate catastrophes, fragile governance, and widespread poverty. Here, CSR is not just a branding exercise; it’s a lifeline for communities the state often fails to reach. And increasingly, it is Pakistan’s banks that are leading this charge.

Perhaps the only sector that has not tasted the woes of financial strain in the last six years in Pakistan is our banking sector. An understandable position as their biggest borrower remains the Pakistani government.

One can hence argue that an industry making a lot of money during destitute times, probably owes some to the less fortunate parts of the society. And in a country increasingly battered by climate-fueled disasters and economic instability, donating opportunities are far from scarce.

And as monetary relaxation would have it, Pakistan’s largest banks are embracing corporate social responsibility (CSR) not as a sideline activity, but as a strategic investment. Both in their nation’s resilience and their brand’s goodwill.

Bank Alfalah has had a leading role in this shift. Their approach is particularly notable for its internal solidarity: the bank has also set aside Rs 500 million to support nearly 480 employees whose homes or assets were damaged by the floods. But the shifting trend has been seen in the larger industry as well.

It is important to note that the following is a comparison of “declared” financial amounts spent and accounted for specifically on social causes, which includes institutional donation. It is very likely that a bank is indirectly adhering to sustainable goals but could not describe the financial impact of it in tangible terms. In fact most of the CSR reports claim much larger contributions than can be found on the respective bank’s books. And it is absolutely plausible that some organisations intangibly contribute much better than others.

The following comparison, however, is purely a comparison of corporate social contribution significant and tangible enough to be on the books of the organisation between the ten biggest banks in Pakistan.

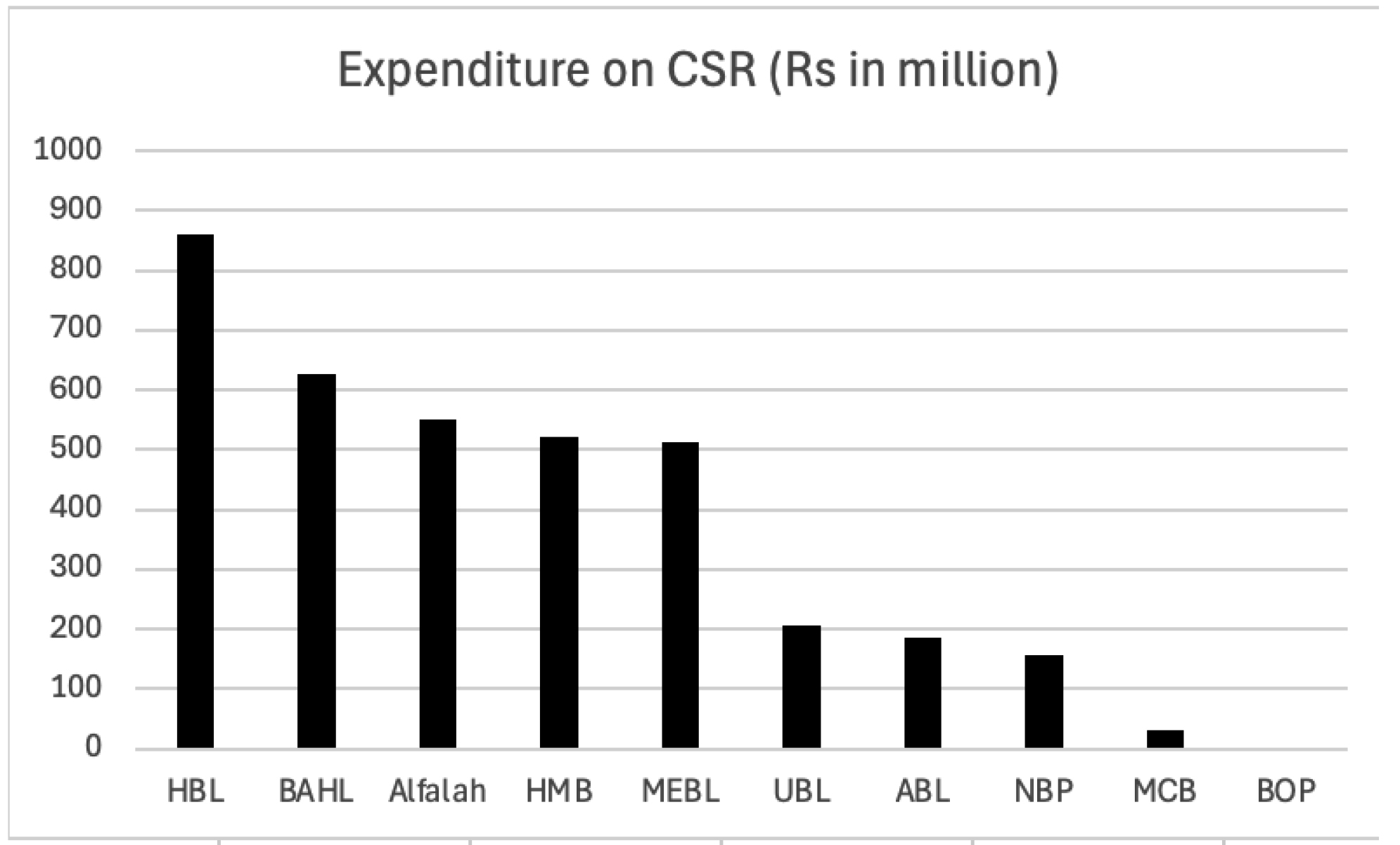

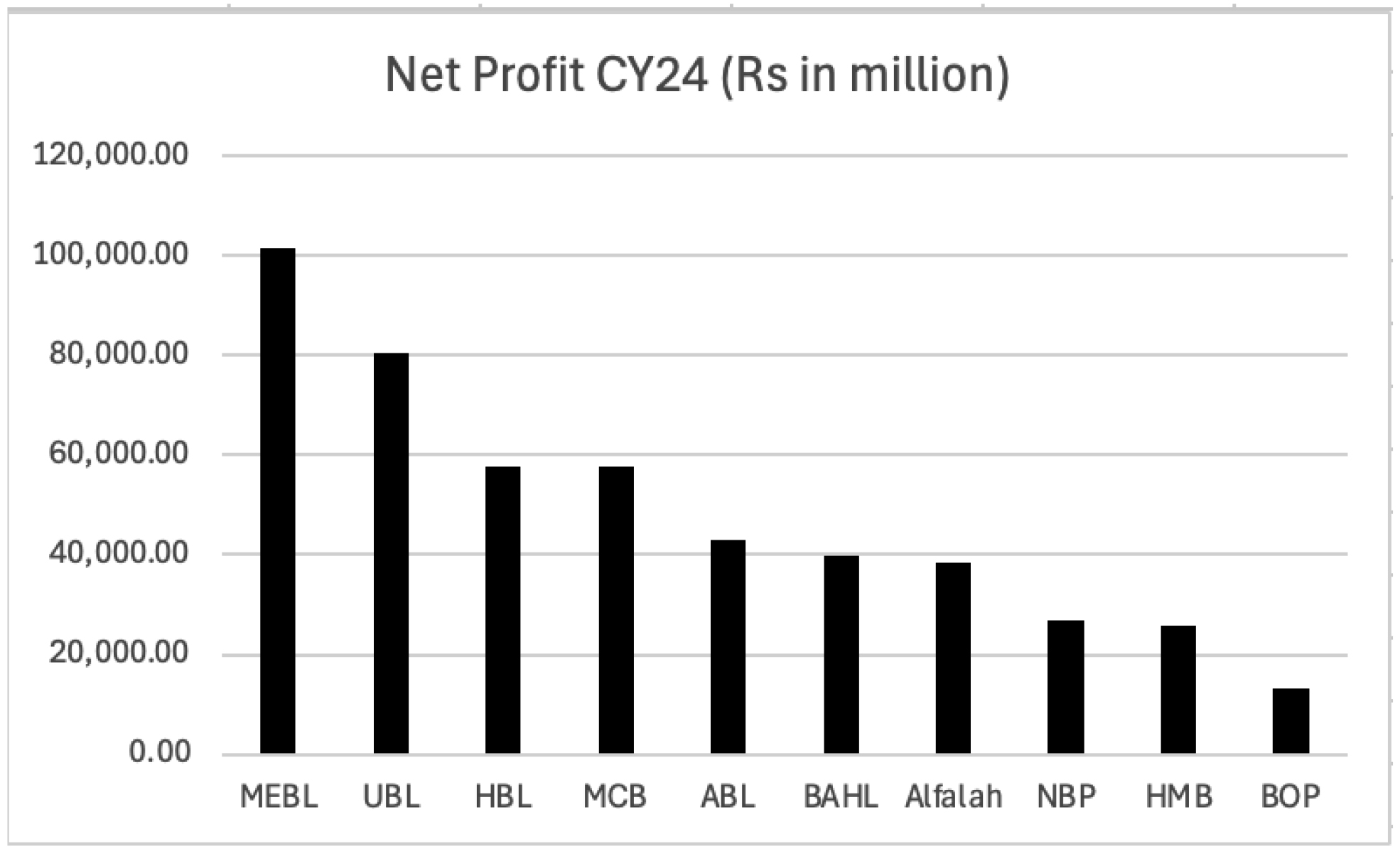

Habib Bank Limited (HBL) spent Rs 861 million on CSR activities in 2024, around 1.49% of its Rs 57.8 billion profit after tax, making it one of the more active contributors among its peers. Bank AL Habib (BAHL), despite earning a lower profit of Rs 39.9 billion, devoted Rs 626.95 million to CSR roughly 1.57%, the highest proportional share across the top ten banks. Bank Alfalah followed closely, with Rs 550.8 million in spending against a Rs38.3 billion profit, equivalent to 1.44%.

Habib Metropolitan Bank (HMB), however, outperformed all in relative terms: it channelled Rs519.95 million 2.02% of its Rsv25.8 billion profit toward social causes, a figure that stands out in an industry where most banks barely cross the 1% threshold. Meezan Bank (MEBL), Pakistan’s largest Islamic bank, allocated Rs 513.76 million, but due to its massive Rs 101.5 billion profit, this amounted to only 0.51%.

United Bank Limited (UBL) and Allied Bank Limited (ABL) both large and well-capitalised, spent Rs205 million and Rs186 million, or 0.25% and 0.43% of their profits, respectively. The National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) committed Rs155.76 million (0.58%) while MCB Bank, despite earning Rs57.6 billion, spent Rs31.6 million (.05%).

Taken together, the numbers suggest that CSR spending in Pakistan’s banking sector remains limited and inconsistent. A few banks notably HMB and BAHL appear to treat it as a defined share of profits, while others approach it as a discretionary afterthought. Compared with Indian banks, which are required to contribute 2% of profits toward CSR under corporate law, Pakistani institutions’ voluntary commitments seem cautious and largely self-regulated.

The debate over whether CSR should be institutionalised or perhaps even mandated continues. Proponents argue that banks, given their role in economic intermediation, have a duty to reinvest in communities they profit from. Critics counter that token donations or photo-op campaigns rarely address systemic issues such as financial exclusion, environmental sustainability, or equitable access to credit.

The moral calculus of giving

The debate over CSR is not just about how much is spent, but also why.

Critics argue that CSR can function as a public relations shield, a way to offset reputational risks, distract from exploitative labor practices, or “greenwash” an unsustainable business model. Others see it as a form of soft power, allowing corporations to extend their influence in areas traditionally reserved for the state.

But the defenders of CSR argue that in a country where the state cannot shoulder the entire social burden, private institutions have both the means and the moral obligation to help. For banks, which sit at the intersection of financial stability and social equity, community investment is not just philanthropy, it’s risk management. A more resilient society is, by extension, a more resilient market.

And for banks like Alfalah, it’s also about narrative positioning themselves not merely as custodians of capital, but as agents of change in an era where capital and conscience must coexist.

CSR in Pakistan is still far from systemic. While banks like Alfalah are often cited as benchmarks spending nearly 1.5% of their net profits. Most corporations spend a fraction of that. The banks lower on the list, for instance, allocated much less to CSR in comparison.

If the threshold seems arbitrary, it’s worth noting that China, Indonesia, the UK, and India have all institutionalized CSR through legal frameworks. By mandating minimum thresholds, they have turned voluntary altruism into predictable, transparent policy. Pakistan, however, still depends on voluntary pledges generous at times, but unpredictable and uneven.

From conscience to structure

Pakistan is a country of charitable people. Giving, in spirit and law, runs deep in its culture. Yet when it comes to institutional charity, CSR; the structure remains fragile.

There is a strong case for making CSR contributions mandatory, provided the state ensures basic business security and reduces regulatory uncertainty. Without that, firms will hesitate to formalize commitments that might later threaten their profitability.

Still, CSR has evolved. For the banks that shape Pakistan’s economy, social responsibility has become a form of identity, a marker of modernity and moral legitimacy. What began as a checkbox in annual reports is now an ongoing negotiation between profit and purpose.

The idea of CSR may still divide economists, but one truth remains: in a country like Pakistan, where the lines between private interest and public good are blurred by necessity, corporate responsibility may well be the only consistent social policy we have left.