A problem with numbers is that they are objective. And that by default does not sit right with the immensely subjective world that we live in. Hard data can take on markedly different meanings depending on who is interpreting it. The same set of figures, valuations, equity levels, debt transfers, and even capital injections can be presented in sharply different ways by government officials, political opponents, and commentators, each emphasising a version that aligns with their own narrative.

In a transaction this complex, where the headline price, the cash to the government, the capital infusion into the airline, and the treatment of debt all differ, the numbers can appear contradictory even when they are technically accurate.

And it’s almost imperative that whenever a national asset gets sold, people argue about the fairness of the deal. After all, the entity was owned by taxpayers and any loss it incurred thereof was being borne by the taxpayers for more than 2 decades. They have all the right to know.

But understanding the net worth of a company is not as simple. Understanding the net worth of a company like PIA, even more so. Add to that a mix of government PR, some accounting gimmick and an opposition so well-adapted to social media, it can spread its ideas like wildfire, and you get a recipe for disaster.

Book Value vs Fair Market Value; Was PIA fairly priced?

To understand the value at which PIA was sold, one first needs to understand the difference between enterprise value, book value and the transaction value. And how much was PIA sold for, will be the transaction value.

According to the scheme of arrangement (SoA) document of April 2024. The total assets owned by PIACL, after transferring some assets to the holding company, was Rs 146.57 billion. Meanwhile the operating entity’s total liabilities (the money it owes to creditors) after the restructuring was measured at Rs 202.27 billion. Of this, the government owed a portion of employee liabilities in pension and post retirement funds, to the tune of Rs 40 billion, not accounted for at the time of the scheme of arrangement.

Taking both cases, the book value, or the net equity of PIACL, the operating entity, amounts to below negative Rs 16 billion. This is also corroborated by the financial statements from June 30, 2023, wherein the operating entity retained assets of around Rs 160 billion and was shouldering remaining liabilities estimated at Rs 175 billion. Estimating the book value to be around negative 15 billion.

By the end of CY2024, the company had already turned some profit and offset some liabilities. And as per the revised and audited financial statements of 2024, PIA’s Net equity, or net assent value was a positive Rs 3.55 billion. While there is little to no clear public data available of the company’s balance sheets after CY2024, pundits claim a higher net equity value after adjustments, some Rs 6 billion and some Rs 9 billion.

But that value is irrelevant. Why? Because the book value of a company is seldom the true representation of a company’s actual worth or a transaction’s worth.

Book value limits the valuation to numbers only, when in reality there are a hundred things that affect the value of a company. Its ability to generate future cash flows, its image, the value of intangible (soft) assets that it owns and anything that has the ability of turning the company around. All of this is valued, not by balance sheets, but by the market.

In fact, this is the very phenomenon that changes stock prices overnight on the back of favourable news items, and is responsible for billions worth of arbitrage in the trading of shares on stock exchanges. The fair value of a company, by definition, is whatever a seller is willing to pay for it.

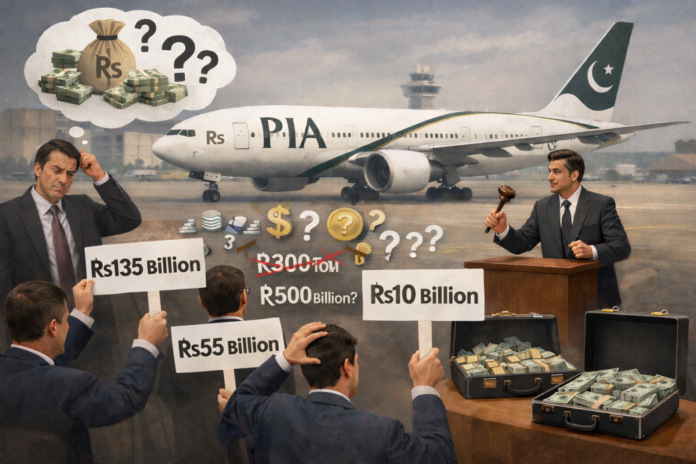

And here is where, dear reader, lies the bottom line. The fair market value of 75% of PIA was determined by a public, clean and non-collusive bidding process. And that value was determined to be Rs 135 billion. However, is that what PIA was sold for?

It is because of this confusion that some commentators argue that, since the government only gets 7.5% of the transaction value, i.e Rs 10.125 billion, the real price that was set for 75% of PIA is actually Rs 10.125 billion.

Lets for a moment, put on a tinfoil hat and indulge the narrative of the deal naysayers. Is Rs 10.125 billion below the book value, thereby favouring the buyer? The answer is no, as made clear by our earlier determination of the value of the company’s net assets.

Even if the transactional amount is taken at a face value of Rs 10.125 billion, it is more than what the books dictate.

This means that there is still some level of positive speculation that the buyer has to make about the company’s future, albeit not as much as the news would have you believe.

Total Consideration and the acquisition price; The real answer:

But let us now, come back to what the transaction would be valued at, if it is to be narrated to someone, say, in the news. While in a privatization deal, the “price” and payment structure are a mutual prerogative because they represent a negotiated compromise between the state’s socio-economic goals and the buyer’s commercial risks.

Rather than a fixed sticker price, the terms are a “package deal” where the government may intentionally accept a lower cash payment in exchange for the buyer assuming specific burdens, such as mandatory capital investment or job protections, which would otherwise cost the state more in the longer run. But in these cases, one should not say that the value of the deal was the enterprise value/ fair market value. That is a misleading statement to the taxpayer, because it is only because of the taxpayer’s involuntary yet crucial hardwork, that has kept PIA afloat.

So by setting these terms together, the seller ensures the entity’s survival and the buyer ensures a path to profitability, making the cash component of the total enterprise value, just a part of the real “transactional value”.

Let us purge all this earlier and understand the transaction with an example.

Imagine PIA is a 4-kanal house in an extremely desirable location, but the structure has deteriorated to the point that no one can actually live in the house. The foundation is cracked, the roof leaks, and some rooms are uninhabitable.

A guy, lets call him Ali, owns 100% of this house, divided into four equal 1-kanal portions each portion representing 25%, and wants to sell it. Let’s assume that there were also some loan repayments and mortgage against the house that Ali has taken upon himself, so as to not scare off buyers.

Now here’s how his transaction maps out:

In an open auction a buyer, lets call him Arif, proposes a Rs135 billion plan. And in this plan only Rs10.125 billion actually goes to Ali as the payment for 75% ownership of the house i.e; 3 kanals.

But why Rs 10.125 billion only?

Because the house, in its current condition, is very hard to live in. Its true pre-repair market value is low, and Ali is essentially selling the bare legal ownership, not a highly functioning asset.

Now some would argue that in its true glory, the house was a spectacle to behold and the locality alone is worth more than 10.125 billion, and Ali is being ripped off, but is he?

The 4-kanal asset is structurally unsound. So Arif must commit Rs 124.875 billion to fix the cracked foundation, replace the roof, rebuild the wiring and plumbing, and make the house liveable again. And the buyer does this not for his three kanals but for the entire house. This includes Ali’s 1 kanal as well.

So what did Ali sell the house for? 10.125 billion? No. Because Arif is paying for the repair of his portion as well. The effective value that Ali generates from this mutual plan with Arif is Rs 41.375 billion. Where he gets Rs 10.125 billion as cash and Rs 31.25 billion worth of repairs for his 25%. (Since Arif repaired the whole house, the proportionate share of repairing Ali’s portion is Rs 31.25 billion).

Once Arif acquires 75% and injects the Rs125 billion, the house becomes structurally sound and usable again. Now the 4-kanal house is effectively worth, the Rs 10.125 billion (what was paid to the seller) + capital injection Rs124.875 billion (renovations), which is equal to Rs135 billion, the final value of Arif’s portion.

The arrangement also states that if Arif wants to purchase the remaining 1 kanal, he can only decide to purchase it after the repairs are majorly paid for. In that case he has to pay the full value for it, which is Rs 45 billion plus the deferment premium at 12%.

Needless to explain, in this analogy, the house is PIA, and the Ali and Arifs are, coincidentally Ali and Arif, Muhammad Ali being the Privatisation Commission chairman (the representative of the GoP), and Arif being Arif Habib.

So here is a simpler way in which the market puts these things: the pre-money enterprise value of PIA is Rs 13.5 billion (Rs 10.125/ 75%). The post money enterprise value of PIA is Rs 180 billion.

The acquisition price, for the most part, is the most relevant number here and that number is neither of the above. From our earlier explanation, we established that the government gets Rs 10.125 billion upfront, and an injection of Rs 31.25 on its behalf. This means that the transactional value of 75% of PIACL is Rs 41.375 billion. Using simple division, we can determine the “price” of the entire PIA as Rs 55.16 billion.

This calculation, is not to be confused with the oversimplified explanation given by the state minister, the next day. Because that calculation determines the value after the determination of a fair market value of PIA, when the value of the government stake had already become Rs 45 billion, which when added to the cash they get i.e; Rs 10.125 billion is Rs 55.125 billion. Even though, surprisingly close, it’s wrong in methodology.

(Note: The 12% premium is not included in our calculation of value at time 0 because it is a deferment premium and it represents the value of money lost in the 15 month process, that is assuming that the Arif Habib consortium chooses to invoke the call option at all.)

Is the PIA sale a scam?

Having a flag carrier is important to the government, whether state-owned or privatised. And a flag carrier that is struggling financially, needs an injection of finance. That is what the deal offers.

That is also the very reason why the bid made by Blue World Group, a year ago, was not as seriously weighed. Because the buyer, in that case, was not looking to revive the airline. It did not have the balance sheet to revive the airline and was not promising a capital injection for said revival. Arif Habib consortium is, and that is why, the privatisation commission will always consider this a more favourable deal.

A similar “low cash, high commitment” structure already occurred during the 2005 privatization of PTCL, where the government sold a 26% stake to Etisalat for $2.6 billion. Much like the PIA deal, the terms were a mutual prerogative that moved beyond a simple cash transfer.

The deal included complex staggered payment schedules and specific management rights. When disputes arose over the transfer of state-owned properties (assets), Etisalat withheld $800 million, a move allowed by the specific contractual terms negotiated to protect the buyer against “unclean” titles.

This shows that in large-scale state-level sales, the final “real price” is a fluid figure dictated by the mutual fulfillment of conditions, such as asset transfers or reinvestment, rather than just the initial bid amount. Saying that the PIA was sold for Rs 10.1 billion is also wrong because it erases the valuation that the company brought in an open bidding, and will have real time implications if the government decides to sell the remaining 25%.

The Airline’s Liabilities and Potential; Key Considerations for the Winning Bidder

With all that in mind, let us come to the extent of the risk/reward ratio that the Arif Habib consortium now has to deal with. The buyer will need to grapple with PIA’s immense financial challenges, but also has the chance of building upon a lost legacy.

With the debt restructured, the successful bidder will have the chance to operate a leaner airline, with a reduced burden of liabilities. A significantly smaller debt stock is expected to improve the cash-flow profile of the privatised entity.

For the winning bidder, the main attraction lies in the opportunity to revamp PIA’s operations while inheriting its vast network of routes and established market presence. The airline’s brand recognition makes it a prime candidate for expansion. It still represents a strategic asset due to its route rights, brand, and foreign-currency revenue potential. These licenses and passages alone, can be valued at a high enough value to have good brand value.

Moreover, the government’s efforts to restructure PIA’s debts make it a more manageable investment than it would have been just a few years ago.

However, the process will not be without challenges. The new owner will need to address PIA’s legacy issues, including its tarnished reputation, inefficient operations, and high overhead costs.

The airline’s workforce, once bloated with over 11,000 employees, has already been reduced to 6,500, but labor concerns will remain a crucial issue. The privatisation terms include protections for employees, ensuring no layoffs for one year and securing their pensions and benefits. With a network of strong employee unions reminiscent of Bhutto’s socialist ideology, human resource management might still be the single biggest concern that the new buyer inherits.

And to top it off, the airline’s financial history is not to be forgotten, the sole reason for why the state has been adamant on selling it. Even though the new entity formed as a result of restructuring PIA’s debts, to make it a more attractive asset, brings in a more attractive set of considerations; the operational efficacy of the airline is thoroughly captured by a decade of financial rot.

While the operating entity turned a profit of Rs 26.2 billion in the CY24, most of it was on the back of taxation rebate. The company, in reality, still made a loss before taxation of Rs 3 billion.

Moreover, a company’s financial future is mostly an echo of its past and PIA’s past is one to forget. PIA’s financial position between 2017 and the first half of 2023 shows persistent operating stress, reflected in consistently negative operating cash flows and a steadily widening equity deficit.

Cash-flow data indicates that the airline generated negative operational cash flows in every year from 2017 to 2022; ranging between Rs 22 billion and Rs 24 billion, annually. In the first half of 2023, operating cash flow briefly turned positive at Rs 15 billion, but this came alongside a sharp rise in financing and investment outflows. Over the full period, operating deficits were largely financed through continued borrowing, shown by the consistently large financing inflows: Rs 33 billion in 2017, Rs 32 billion in 2018, Rs 19 billion in 2019, Rs 31 billion in 2021, and Rs 4 billion in 2022.

The reliance on borrowing is also reflected in the airline’s rising cost of finance, which increased from Rs 15 billion in 2017 to Rs 50 billion in 2022. Finance costs remained one of the airline’s largest expense lines throughout the period, often overshadowing any cash improvements from operations or investments. The elevated servicing burden contributed materially to the airline’s continuing losses and liquidity strain, prompting repeated engagement with lenders and the federal government over restructuring options.

The accumulated impact of recurring operating losses and growing financial liabilities is also visible in PIA’s (the operating entity before restructuring) negative net worth, which expanded steadily from –Rs 291 billion in 2017 to –Rs 649 billion by June 2023.

This is the context in which the government approved a significant restructuring of PIA’s liabilities. The scale of this negative outlook underscores the challenge prospective buyers face when assessing the airline’s balance sheet without restructuring.

There is no question that PIA was a” white elephant”. There should be no question that the sale of PIA is a good decision for the country. The sale could be argued as a profitable one based on the earlier estimations of the company’s fair value, and it could also be argued as a “bad deal” based on the same explanation.

Answers of questions like, whether the deal was fairly held out? Was the bidding even fair, such that it can represent the fair value of the company? Is it all a giant scam and conspiracy? depend entirely upon who you ask. And regardless of those answers, the successful sale of PIA is a good riddance for the taxpayer.

Even if this specific bidding was underpriced, I am just happy, seeing that a majority of taxpayers money is not being wasted on a corrupt liability like PIA

Thankfully it is sold. It had billions of rupees in liability and losses with 6,200 employees, no one really would go for this deal and it was proven. Tax payers money saved.

It’s strange to see wise men discuss profit in a case which was screwing the economy of a country. The best part is its sold and that too bought by a local firm. I think youthias should stop trying to be wise, as biggest screw up was from IK and his Aviation minister which further complicated the entire matter. PIA is now in the right hands. PPP is also unhappy because for years they did political employment in PIA. Let’s celebrate privatisation and do it with Karachi steel Mills and other loss making entries

All the **Wisemen and Scammers can answers the PUBLIC TAX MONEY WAS SCOOPED BY THESE CORRUPT RULING ELITE CLASSES OF POLITICIANS AND KHAKIS IN DEFENCE MINISTRY SHOULD BE BROUGHT UNDER CRIMINAL CASES TO THE COURTS SHOULD BE HANGED??**.