Nova Minerals, a mining exploration and development company focused on gold and critical minerals, recently issued a clarification. And this clarification tells a tale.

In December last year, it was reported that the NASDAQ- and ASX-listed company had entered into an agreement with Pakistan to import over 100 tonnes of antimony for around USD 2 million. This antimony would then be tested and processed in Alaska. Eventually, a downstream processing site would also be set up in Pakistan.

Nova’s clarification concerned this reporting. In a press release, the company hedged itself against the reports of an agreement in the works, and stated that any discussions were in the exploratory stages, with nothing solid that had been agreed. It was premature to read anything practically significant and binding in these talks.

Now Pakistan has prided itself on its mineral deposits, and there is a good reason for this. The existing copper, gold, and silver extraction projects in Balochistan, such as Reko Dik and Saindak, contain massive amounts of ores worth tens of billions, and have brought in a lot of money to the government.

Antimony, however, is another thing, literally and figuratively. It was only last year that it was announced that significant deposits of this metal had been found in Pakistan. While this was immediately taken up and proclaimed as a promise of Pakistan’s great potential, there is still some hesitation around what it might actually translate into.

The promises are there, but the indicators that these might sustainably bear fruit are not many. Considering the infrastructural constraints, political instability in Balochistan, and geopolitical pressures, the project’s road to reality is beset by various blocks.

The Strategic Significance of Antimony:

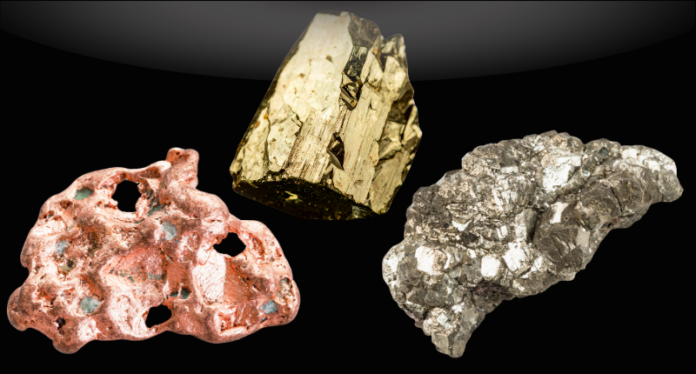

Antimony is a metallic element that exists as “lustrous silvery bluish white solid that is very brittle and has a flaky texture”. It is used by multiple sectors (electrical, battery systems, semiconductors, and energy), but perhaps the most strategically relevant use of this metal is in the military industry, where it is used in the production of night vision goggles, bullet casings, tanks, explosives, flares, nuclear weapons, and infrared sensors used in missiles.

The global antimony market is dominated by China, which produces almost 50% of the world’s total antimony, controls around a third of the global antimony reserves, and possesses around 60% of the global processing capacity.

The United States, on the other hand, produces almost none of antimony on its own, but relies instead on imports to supply its local industry needs. This is seen as a problem in Washington, which, especially recently, has been aiming to reduce its reliance on China for access to critical and rare minerals and metals. In light of China’s ban on antimony exports to the US instituted in September 2024 (but suspended in November 2025), the United States designed antimony as a “critical defence material,” and started exploring other potential suppliers of the critical metalloid.

In fact, in October last year, the United States Department of War deployed almost USD 1 billion to replenish domestic stockpiles of antimony to be used in defence applications. Companies like Nova Minerals, which was granted a USD 43.4 million award to source and produce military-grade antimony trisulfide, are seen as a critical part of this venture. And so is looking for antimony from elsewhere while domestic production is set up.

Where Pakistan Comes In:

In early 2025, it was announced that large quantities of antimony had been discovered in Balochistan, especially in regions of Zhob, Pishin, and Killa Abdullah.

According to the US Geological Survey, however, Pakistan’s reserves account for just over 1 percent of the global total, concentrated mostly along the volatile border with Afghanistan. Local production of antimony, similarly, is low. In 2024, for instance, Pakistan was estimated to have produced around only around 0.25 percent of global antimony.

In any case, the Pakistan government had extolled the potential of these minerals – as well as others – to contribute to the country’s exports and reduce some pressure on the terrible trade balance. And the United States looking for non-China suppliers found in Pakistan a possible partner. This, mind you, is also the time after the clash with India mid-2025, after which Pakistan’s standing in Washington considerably increased.

In early September 2025, Pakistan through Frontier Works Organization (FWO) and the United States through U.S. Strategic Metals (USSM) signed a USD 500 million agreement, whereby Pakistan would export to the United States readily available minerals including antimony, copper, gold, tungsten, and other rare earth minerals.

This agreement was posited as part of a broader effort to collaborate on “critical minerals essential for the defence, aerospace and technology industries”. It outlined a three-phased framework, where the first phase would involve the export of readily available minerals, while the second phase would focus on capacity building in Pakistan, while the third phase would lead to large scale mining and production.

Pursuant to the agreement, Pakistan sent its first shipment of these critical and rare earth minerals to the United States in October 2025, mainly for quality testing. The real commercial benefit would still be in the future.

Since then, Nova Minerals has also been in talks with various stakeholders, reportedly including Himalayan Earth Exploration, to explore antimony resources in Pakistan, but as mentioned earlier, Nova recently said nothing substantial had materialised, and the talks were still wallowing in the exploratory stage.

Whatever the outcome may be, Pakistan has been trying to position itself as a strategic partner to the United States, and this effort to enter into agreements to supply critical and rare earth minerals forms a part of it.

The Challenges Lying Ahead:

The benefits touted are many, but to the general tune of it being a great source of potential revenue for Pakistan in the future. While there might be credence to this view – Pakistan, after all, does have the reserves – it is unclear how big of an opportunity antimony might present on its own. Even the amount floated around for the imaginary Nova deal was a mere USD 2 million. On the other hand, while the agreement with USSM was worth much more (250 times more), it is not confirmed that it was a binding contract. The financing and legal structure of the agreement also remains unclear. It, therefore, is not much to really bank on, considering where we currently are.

At the same time, as we have seen, Pakistan does not produce a lot of antimony on a global scale. While probably not much can be done about it considering it just doesn’t have vast reserves of the element, antimony alone cannot be seen as a panacea, but must be viewed in the context of the general mining industry, including the extraction and production of other critical and rare earth minerals.

Here, the situation doesn’t appear to be too great. In fact, while the number of USD 6 trillion is frequently thrown around as the worth of Pakistan’s natural resources, the contributions to the national GDP amount to less than 3 percent. Contributions to global trade are a pitiful 0.1 percent, and it is not clear if anything more than a small percentage of that figure will be accessible in the near future.

This disparity between the potential of Pakistan’s natural resources and what is actually obtained from them points to systemic inadequacies, which raise questions about the viability of this broader push towards antimony as a source of economic and strategic advantage.

Most of Pakistan’s mining production is at the lower end of the value chain, and the situation with antimony does not appear to be anything more. Pakistan lacks large-scale refining and metallurgical capacity to process critical and rare earth minerals at home. In fact, Pakistan had proposed Oman as a potential refining partner for extracted antimony. This, of course, would not only be cumbersome – transporting the extracted minerals across rugged terrain – but also cause the prices to rise, and expose the supply chain to geopolitical risk.

At the same time, Pakistan hasn’t had a consistent mineral strategy, which has exposed private enterprises to great risk, especially in a capital-intensive venture such as this. The Mines and Minerals Act 2025 aimed to provide a coherent framework to promote mining, but the effort – with the Balochistan version of the Act – fell into controversy. The opposition parties rejected it on account of its giving more power to the centre over the province’s natural resources, something that’s long been a point of contention.

And this brings us to the next point: the history of Balochistan’s resources and their extraction. While other provinces have benefitted much from resources found in Balochistan (such as natural gas, copper, gold, etc.), the people of Balochistan have found little corresponding increase in their standards of life. In fact, this is one of the main terms of resentment within this province, where political actors rightfully decry what they term exploitation of the province’s resource with not a fair share in the proceeding proceeds from them. And, whether Balochistan would get a fair share from what antimony might bring in remains to be seen.

A relevant point is the volatile situation in the Balochistan province, where insurgency is on the rise. While Pakistan might be able to protect the mining sites, which have also been recipients of attacks, it is a whole other question whether transportation and logistical routes would see equivalent protection. Considering that Pakistan does not have an advanced transportation network for conveying mined material from areas far away from the metropoles, it remains to be seen how antimony’s supply chain would be modernised to really cash in on the deposits.

And, to top it all, since the antimony opportunity is geopolitically strategic, it would require diplomatic mastery by Pakistan to accommodate separate agreements with both the United States and China, the latter of whom already has multiple ongoing projects in the same province. Given that these two countries are at great odds in terms of their geopolitical and economic manoeuvring, Pakistan would also need to strike a delicate balance to bolster its own position without alienating either of the two.

Pakistan would, therefore, require a coherent and consistent mining and political strategy, government-led infrastructural investment, and patient implementation to address these problems. These efforts must also be part of a broader framework that not only encapsulates the current metal mining efforts, but also accounts for the critical and rare earth minerals found in Pakistan. Failing these, the country might be stuck in the role of an intermittent supplier of antimony, with little economic or strategic gain to show for it.