“Mein bara ho kar fauji banoon ga”

Chances are, if you have grown up in Pakistan, you have probably heard the above sentence. The army is so intertwined with the very fabric of the country (for reasons beyond the scope of this magazine), that it is not uncommon for children to want to join the sixth largest army in the world (ranked by military personnel).

Except perhaps if you really want your kids to succeed, maybe that adage should be amended to “mein bara ho kar Fauji mein kaam karoon ga”. In 1954, the Pakistan Army set up the Fauji Foundation, as a charitable trust initially designed to help provide welfare for the army’s retired soldiers as well as their dependents. In 2020, this charitable trust is almost unrecognisable.

It has sprawled into a massive conglomerate, that runs 21 associated companies, and three fully owned companies, in industries as varied as fertilisers, cement, power, oil, gas, food, grain, and even banking (Askari Bank). On top of that, it operates 15 medical facilities, 100 schools and colleges, 65 vocational training centers and nine technical training centers across the country. By its own estimates, its welfare programs serve 9 million beneficiaries.

And where is the money for this welfare program coming from? The two most important, and most lucrative, of those companies are Fauji Fertilizer Bin Qasim Ltd (FFBL), and Fauji Fertilizer Company (FFC). Fauji Foundation owns 18.3% share of the former and owns 44.4% of the latter. FFC in turn owns 49.9% of FFBL.

In market parlance, FFC is known as “Bara Fauji” and FFBL is known as “Chhota Fauji”. At Profit, we like to adhere to market principles, which is how we will also refer to the two companies.

Big Fauji is the older of the two, and was founded in 1978. Domiciled in Rawalpindi (big surprise), the principal activity of the company is manufacturing, purchasing and marketing of fertilizers and chemicals. It is the largest urea manufacturer in the country, has two production plants in Ghotki, Sindh, and Sadiqabad, Punjab, and 63 district offices and 183 warehouses.

Meanwhile, Little Fauji was initially formed as a venture between Big Fauji and the Jordan Fertilizer Company, to make a complex that would manufacture diammonium phosphate (DAP) and granular urea in Pakistan. It started production in the year 2000, and is still the only manufacturer of those two products in the country.

On January 28 and 26, both Big and Little Fauji respectively released their financial statements for the year ending December 2020. The results are quite divergent: Big Fauji just managed to scrape through a profit, but overall had less sales than the previous year. Meanwhile, Little Fauji had a blowout growth year, going from a loss in 2019, to a sizable profit in 2020.

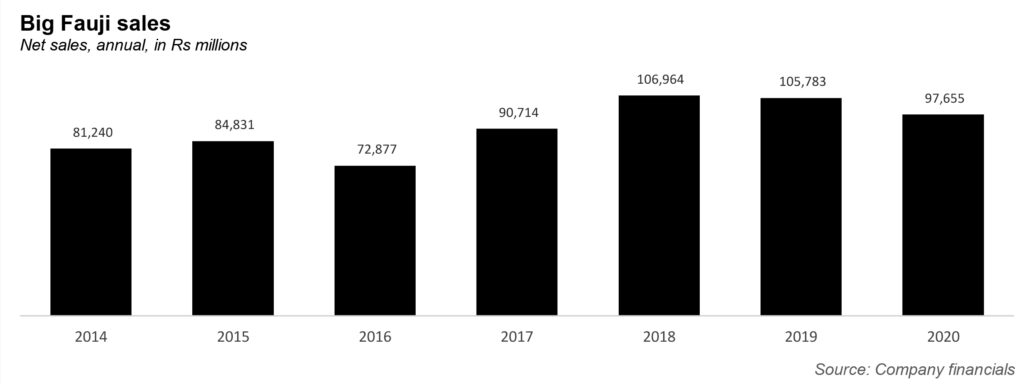

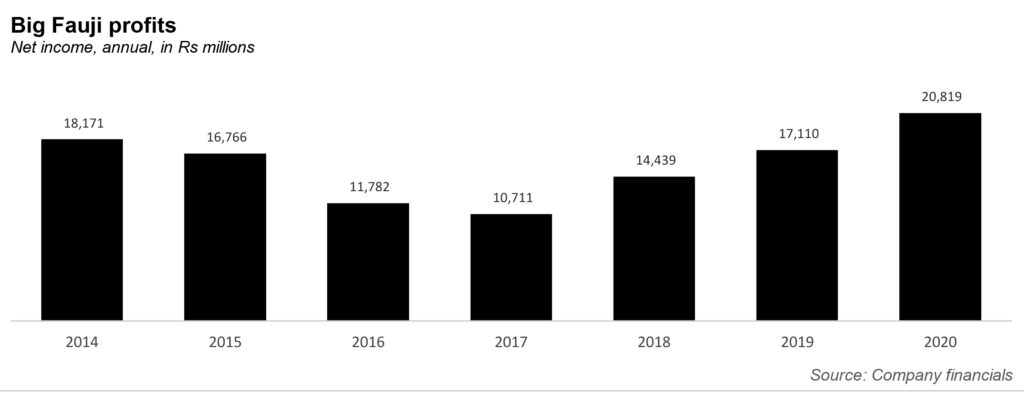

First, let’s take a look at Big Fauji. Its sales have been generally in the same ballpark: In 2014, its sales stood at Rs81 billion, before dropping to Rs73 billion in 2016. In 2018, sales crossed the Rs100 billion mark, before dropping to Rs98 billion in 2020. The company’s net income, however, has not followed this trajectory. In 2014, the company’s profit after tax stood at Rs18 billion, a figure it would not cross again until 2020. In 2016 and 2017, the company’s net income tumbled to Rs12 billion and Rs11 billion, before steadily climbing again in the subsequent years. In 2019, net income stood at Rs17 billion; it rose to Rs20 billion the next year.

What happened? According to Big Fauji’s 2019 annual report, the net profit fell between the years 2014 and 2017, due to a litany of problems: “persistent government intervention in product pricing under the subsidy scheme, levy of discriminatory GIDC, higher finance cost, lower dividend income and higher taxation charges”. In addition, cost of sales shot up in 2017, while gas costs increased in 2018, somewhat jolting the company. Still the company scraped through in 2018 and 2019, due to an improvement in fertilizer selling prices and “record” income from investment.

As for the year 2020, the company’s gross profit is actually similar to last years (Rs32 billion, compared to Rs31 billion). The difference is, in 2020, BIg Fauji gained almost Rs6 billion from the extinguishment of the GIDC liability. This helped make up for other losses, which is why that year’s profit is higher than 2019’s.

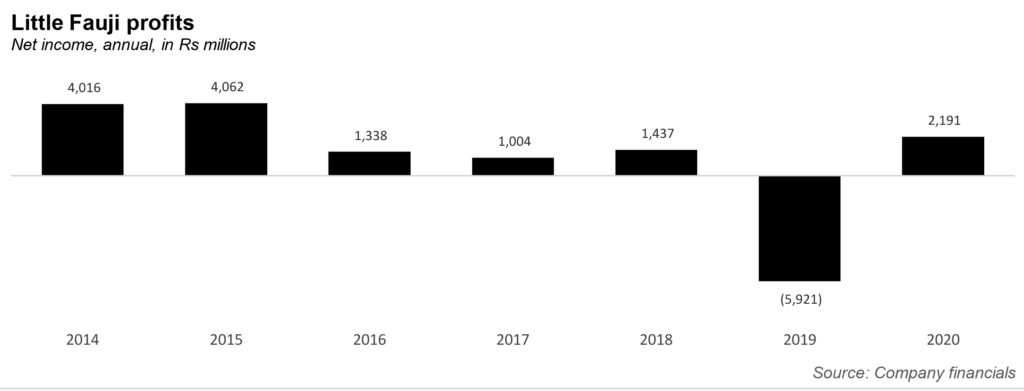

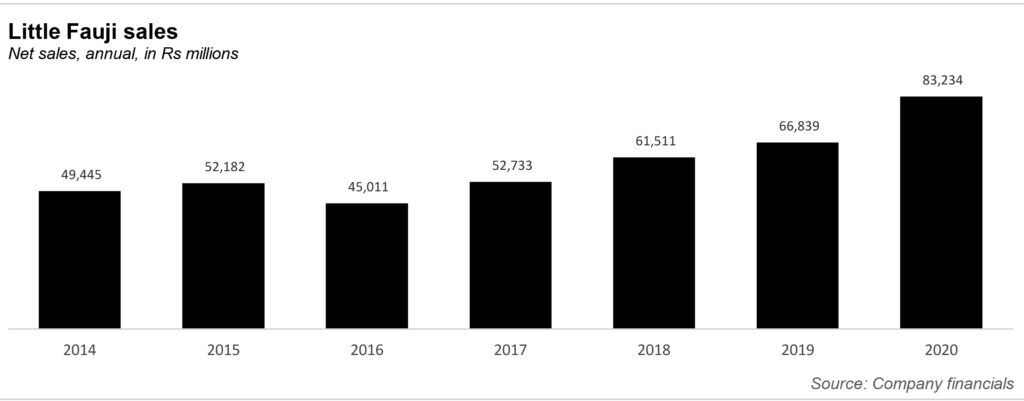

Now, look at Little Fauji. Between 2014 and 2020, the company’s sales have only fallen year-on-year once. In 2014, sales stood at Rs49 billion; 2017, sales stood at Rs53 billion, climbed to Rs67 billion in 2019, and then wildly jumped to Rs83 billion in 2020. But the company’s net income tells a different story: it hovered around the Rs4 billion mark in 2014 and 2015, fell drastically to the Rs1 billion mark for the next three years, and then actually went negative in 2019, with a loss of Rs6 billion. The year 2020 is remarkable because the company actually made a profit of Rs2 billion.

Over here, the story is a bit simpler: that the year 2019 was an awful outlier in an otherwise healthy company. Little Fauji’s annual report pointed out several problems: soaring exchange rate which increased the costs of imported raw material; inflation increasing the costs of local material. Meanwhile, the import and sale of cheaper DAP hampered Little Fauji’s fertilizer off-take, forcing it to carry an inventory of 189 thousand tonnes at the year end.

In comparison, the year 2020 was a much better year. The company’s finance and administrative costs were lower, other income was higher, and it even gained Rs2.7 billion from the GIDC gain. But fundamentally, it just happened to sell a lot more this year, resulting in the highest profit it has seen in five years.