When news about electronic money institutions (EMIs), including SadaPay and NayaPay, started gaining traction in late 2021 and early 2022, it was exciting for anyone tired of the way banks in Pakistan worked. Customers would no longer have to visit a branch any time they needed something done, and signing up for a debit card that could be used for international transactions appeared to be easier than ever. There was a palpable feeling that the payments system would finally have something new, something better, and that a financial revolution was just around the corner.

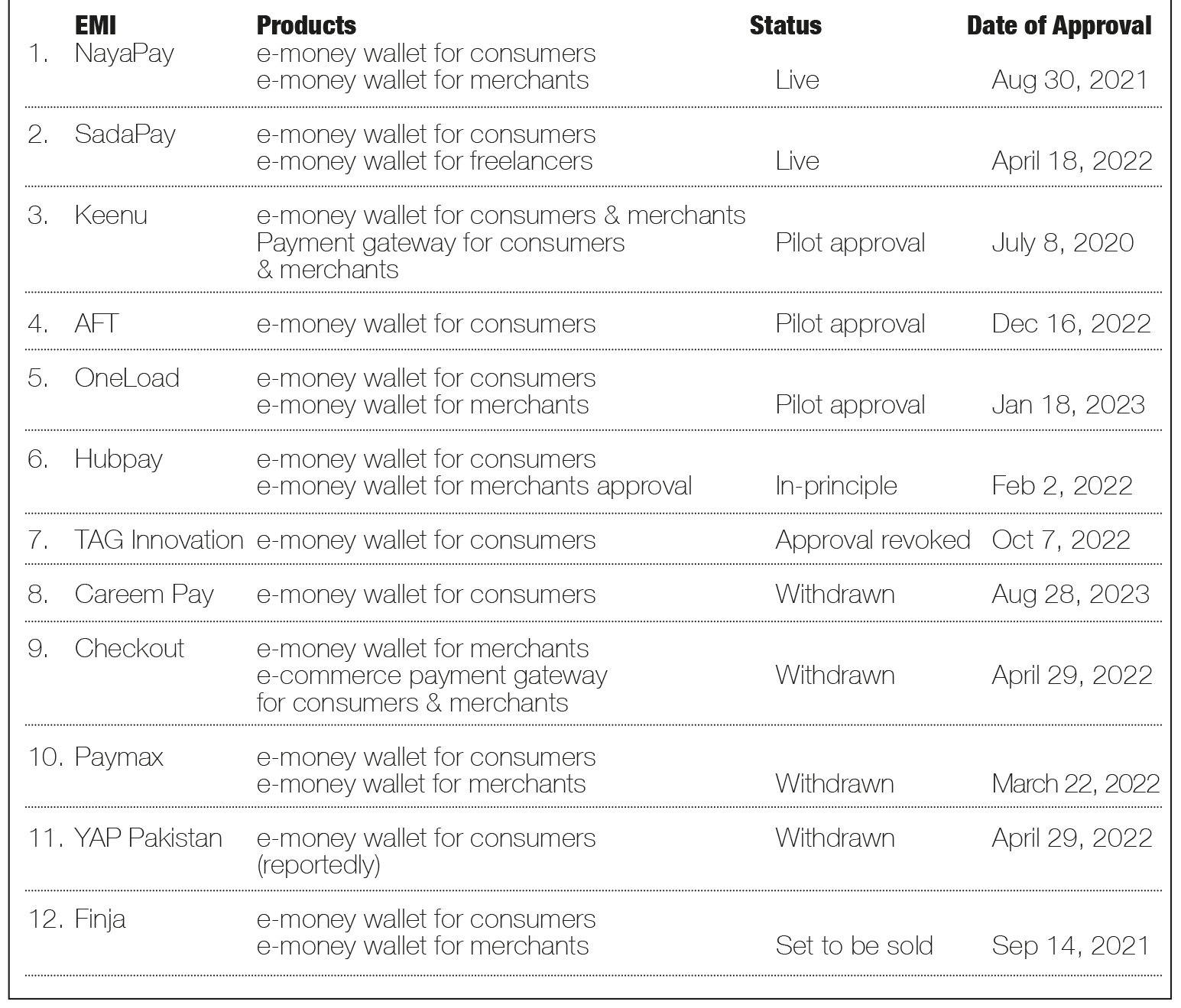

But almost two years down the line, that optimism is fading. Almost half of the 12 entities that were in the running for an EMI licence or had already received it have either withdrawn or shut down for other reasons.

First, in October 2022, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) revoked TAG Innovation’s pilot operations approval citing regulatory violations and other concerns. Then, in April 2023, UK-based company Checkout withdrew its EMI license application. In August 2023, Careem Pay followed. Meanwhile, in October 2023, Finja sold its EMI operations to Opay International. Separately, there are reports that YAP Pakistan has also withdrawn its license, though Profit was unable to get a confirmation from the company on the matter.

Under the SBP’s rules, EMIs are granted a licence in three stages: in-principle approval, approval for commencement of pilot operations and the final approval or licence. Only four companies have been granted the licence — NayaPay, Finja, Paymax and SadaPay. So, it came as a bit of a shock — especially weeks after news that Finja was set to be acquired — that in October 2023 Paymax had requested the closure of business and withdrawal of its licence. Profit reached out to Paymax’s CEO to ask why the company had decided to withdraw its licence, but was informed that there was a hold on external communication at present.

The consistent withdrawals of EMI licence applications has raised questions about the EMIs’ business models and their sustainability. In this article, Profit attempts to find the answers.

Why did EMIs close shop?

Razor-thin margins and limited revenue sources

There are two ways a typical EMI makes money, according to SadaPay Chief Operating Officer (COO) Omer Salimullah. First, it can use deposits to invest in government securities such as T-bills, which have a return of 21% to 23% in the current high interest rate environment. EMIs were previously allowed to invest up to 50% of the last three months’ daily average outstanding e-money balance; this was increased to 75% in June 2023. “This is a significant line of revenue”, he said.

However, EMIs that are focused mainly on e-commerce and point-of-sale transactions earn primarily from a transaction fee, which is typically 1%. This fee is paid mostly by merchants, Salimullah said. However, at times, merchants include the fee in the customers’ bills after informing them, the COO said, adding that this scenario was changing rapidly.

But are these two sources of revenue enough, especially given the wallet transaction limits set by the SBP? Banker and financial services consultant Mir Nejib Rahman believes not. In a conversation with Profit, he pointed out how wallet limitations have affected EMIs’ business.

In June this year, the SBP revised regulations allowing EMI customers who have completed their biometric verification from NADRA to make transactions of up to Rs 400,000 per month. However, this is not enough, according to Rahman.

Commercial banks and microfinance banks (MFBs) invest heavily in government securities, which accounts for 60% of their interest income, while another 30% of it is generated through corporate lending, agricultural lending, and consumer lending, he elaborated. All these venues remain unavailable to EMIs as they can only do transactions, and not lending – for which they require a non-banking financial institution licence from the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan, similar to what Finja did.

“You cannot earn [enough] purely on a transaction basis on an EMI licence. Based on my own calculations, an EMI cannot make money from that in the first five years at least,” he added. For these initial years, he said, EMIs would need strong investors to carry them. This is because the transactional charges are very little, or in most cases, non-existent.

Meanwhile, Amer Pasha, former country head for VISA, said one needs to look at the different licences offered by the SBP and what sets each apart. There are microfinance bank licences such as the one that EasyPaisa has, payment service providers and payment service operators such as 1Link and NIFT, EMIs, and most recently, digital bank licences.

“If you go back in time, telcos, including EasyPaisa and Jazzcash, acquired microfinance bank licences only so they could operate in the payments space. They had no intention of being microfinance lending banks. Later, the State Bank introduced EMI licences and now, digital bank licences,” he said.

At the core of it, a customer can make payments using their Easypaisa or Jazzcash accounts, 1Link via their bank account, EMIs, and in the future, digital banks as well. If payments can be done through all of these, what really sets EMIs apart? According to Pasha, nothing really.

“In my assessment, there is no real benefit of operating any kind of business solely on an EMI licence. If you want to be a full-service bank, there’s a digital bank licence for that. And people who want to operate in that space have gotten that licence because payments, per se, cannot stand on their own unless there are huge volumes. It’s a very, very razor-thin margin business,” Pasha commented.

“What is the use case?” Rahman asked separately. If a consumer already had a debit card from a commercial bank, why would they choose to get one from an EMI as well? He acknowledged that while the product was the same, the experience differed. However, the problem was how to make money. Sooner or later, the EMIs would also have to impose a transaction fee (or increase it if it already existed), he said.

But then again, would that be enough, he questioned. “Bring a use case that is different. What gap are you filling in the market?”

EMIs were being squeezed from all ends, Pasha said, adding that they were not likely to have much success unless they could diversify. “Just operating within the confines of an EMI licence is getting tougher and tougher.”

Marketing and people

According to Salimullah: “Payments, all over the world, is a very low-margin business. We’re only getting 1% of the transaction. So what that means is, if you want to make money and be profitable, you have to keep a very close eye on your bottom line. If you can control your expenses, then these two revenue lines can add up to something that is meaningful. If you let your costs balloon out, then that is a problem.”

The biggest expense for a startup is marketing, according to the SadaPay COO. This is where outflows can rack up quickly while inflows are still low. One reason that SadaPay and NayaPay have survived, and perhaps thrive, according to him, is that both EMIs kept a very close check on their marketing expenses.

“As far as SadaPay is concerned, we have spent almost zero on paid marketing. We have scaled in a very non-traditional way i.e. word of mouth. We created experiences that people were almost forced to tell their friends and family about,” he said. “I think NayaPay is also very concentrated on this side of things. I haven’t seen them spend any real money on marketing.”

“Where I think we have done better than non-fintech startups is that we didn’t blow a lot of money on marketing. So, that’s why we have been able to control our bottomline,” Salimullah added.

Besides low-margins and overspending on marketing, another reason why some EMIs may have given up was because they were unable to create a team they felt comfortable going to the market with, according to the SadaPay COO.

“One of Pakistan’s biggest problems with scaling in any industry, especially fintech, is that unfortunately, we do not have the talent base that we need to scale 10 to 12 EMIs, five digital retail banks and on top of that, digital departments in 30 plus banks. We just do not have the people. And we do not have the mindset we need to scale this.”

Those companies may have looked for people who could make their plans successful but realised there were not many out there and then wondered how to build their EMI, he continued. “It is a low-margin business, the economic conditions are undoubtedly tough. [They must have thought,] ‘where are the people who can create this sort of company and fight against all the challenges that we have?’”

“So, I think that would’ve played a big part in their thinking to just wrap it up and that it’s just not worth it. And thinking, ‘we can’t keep holding on to this licence forever because there are some compliances and overheads because of it’. I’m just guessing – they must have thought it is just too hard at this point to do this in Pakistan and they exited,” he concluded.

Rahman also acknowledged that not being able to find the right people was “definitely one factor”.

Targeting the underbanked vs the unbanked

A major factor that limits the potential of EMIs, according to both Rahman and Pasha, was that their area of focus has been the underbanked, not the unbanked. Put in the simplest terms, the unbanked are those with no access to the banking system. For example, a domestic worker whose every transaction is in cash and who has never had a bank account. Meanwhile, the underbanked have some access to the banking system. For instance, a lower middle class family of five, which mainly uses the account of one person to deposit or withdraw money, or make payments for anyone in the family.

Rahman noted that one of the primary purposes for introducing EMI licences, in the SBP’s own words, was to promote digital payments and increase financial inclusion. However, it would be hard to achieve that goal if EMIs continued to operate in the big cities and focused solely on the middle and upper classes.

“What marketing have EMIs done in second and third-tier cities? Look at all the EMIs marketing material – it is mainly in English. It is apparent from their marketing strategy on social media that they are only targeting middle and upper classes.”

According to the 2023 census, Pakistan’s total population stands at around 24 crores. This is roughly the same number as total accounts in the country encompassing scheduled banks, MFBs and MFIs, and branchless banking wallets. “This means there is a very high level of duplication and triplication, and we do not know the unique customer accounts,” Rahman pointed out. This leads to questions whether the EMIs have sized the market correctly, and if their focus remains on the middle and upper class, whether the market they are targeting will be large enough to generate enough revenue to be sustainable, he added.

Meanwhile, Pasha pointed out that Jazzcash and Easypaisa were targeting the unbanked while EMIs, such as SadaPay and NayaPay, were going after the underbanked because they wanted to increase the number of transactions they were processing. “This is why they [SadaPay in this case] are looking at freelancers because they want money to be deposited into wallets from abroad,” he said, adding however, that there was nothing stopping commercial banks from attempting something similar.

Tough environment?

Pasha rejected the assumption that EMIs withdrew because they failed to analyse the market correctly, attributing it instead to inconsistent policies. “When someone was applying for an EMI licence, a digital banking licence was nowhere on the horizon. So, you could argue that inconsistent policies of the government don’t help these companies. They applied for an EMI licence, they went through the bureaucracy and everything just to find out that now there’s a digital banking licence that will be given. I don’t think it’s the fault of the companies that applied for an EMI licence.”

When asked whether the economic situation of the country could have been a reason for certain EMIs deciding to shut down, SadaPay COO Salimullah said not really. “I feel Pakistan is a non-obvious opportunity. It is not an easy opportunity but we have an American founder who has scaled the company from zero to this size and we are overcoming all the challenges that we faced one by one. It is not impossible by any means. It requires a team and a mindset that is about overcoming challenges and never really complaining.”

Talking about SadaPay, he said the startup was founded because there were problems in the financial sector and the EMI was very well-placed to solve them. For instance, SadaPay saw that freelancers were struggling to receive payments from abroad, so the EMI integrated Apple Pay and Google Pay.

EMIs could also look at solving problems in the insurance sector, and offer avenues to invest in mutual funds, he said. He also brought up lending – which both Rahman and Pasha referred to, and which is currently not allowed under an EMI licence.

“I think anybody complaining about a tough economic situation is just giving up. Where there are problems, there are also opportunities, and SadaPay and NayaPay are testament to the fact that this never say never attitude gets you places,” Salimullah said.

“I do not subscribe to this narrative that Pakistan is some other planet and this is some weird economic scenario that is impossible to work in,” he iterated.

So, with all said and done, is the current business model sustainable? Pasha said no. “The companies applied for EMI licences because they saw an area that banks were not pursuing. If the banks did what they were supposed to do and took care of all the customers, the EMIs would not even have had a window of opportunity.”

But if the commercial banks level up their game and/or once the DRBs come into play and if their service is better, what happens then? “What I foresee happening is that only 2 to 3 companies will be left in the EMI space,” Pasha commented.

Rahman pointed out that at the end of the day, investors wanted to make money. And if an EMI was unable to make money for the first five years, that was a problem. It was costly to operate on an EMI licence unless the company started lending, which was what Finja had done, he said.

“EMIs cannot make money from transactions. It cannot be sustainable. Even Raast (the State Bank’s payment system) is not sustainable,” he added.

The financial services consultant noted that the economic and political uncertainty, which has marked much of the previous and the current year, has also been a factor. He mentioned a Middle-East-based firm he was advising that was interested in obtaining an EMI licence in Pakistan but pulled back because of the prevailing situation.

“The investors who have already committed are also now thinking that their initial projections may no longer be accurate. Basically, a bit of reality has hit.”

[Profit also reached out to NayaPay but they were unavailable for detailed comments.]

What about the future?

Does this mean it is all doom and gloom? No.

Rahman said opportunities “definitely” exist. Pakistan is a huge market but it would depend on whether the EMIs targeted all of it, in a language that enough people understand. After all, over 61% of the population lives in rural areas. Whichever EMI could reach them would do well, he commented.

“The first test is who can survive three years,” he said, adding that one way to do that would be for EMIs to start charging transaction fees (or increasing them if they already are). But fee income would still not generate the same revenue as interest income, he said, stressing that this was why EMIs needed to move towards lending.

Salimullah appeared to have the same view, saying “lending is the next frontier.”

“SadaPay and NayaPay have solved payments to a large extent. The experience in the last 1.5 to 2 years has completely changed for the average Pakistani consumer,” he continued. “We need to take that innovative mindset to lending.”

This was where EMIs required the State Bank’s help, the COO said. He shared that the central bank was already working on a regulatory framework for open banking — a mechanism that allows third-party apps to access consumer banking and financial data via application programming interfaces — but requested it to accelerate the process.

“Let’s say you have a bank account in UBL or HBL. We should be allowed to access that data stored with them, compile it and give a credit score on the basis of which we could lend. This is the next great unlock when it comes to fintech innovation in Pakistan,” he propounded.

The State Bank has broadened the scope of EMI operations this year, revising the regulations in June 2023 to allow EMIs to increase wallet limits, offer new payment services such as payments aggregation, bill/invoice aggregation, escrow services for domestic e-commerce transactions, services via APIs to financial institutions/fintechs, and inward cross-border remittances.

Salimullah was clearly excited about the future. “EMI is a great licence. It is a fantastic licence,” he told Profit.

EMI has potential to reach the masses in the rural areas and they definitely need a strategy for that. Reaching out to freelancers is a great step because that would somehow introduce them to people in villages as most of the youth is going for freelancers specifically in rural areas due to no job opportunities. But they should somehow reach the farmers as well because those are the people who have money but don’t keep in banks. SBP should also penalize conventional banks like HBL specifically because they don’t allow to send more than 10k to SadaPay account. That’s why I hate HBL for such cheap tactics and don’t keep any a penny in their account whenever possible

As technology evolves, new techniques and methods for mitigating EMI will continue to emerge.

I’m a SadaBiz user. Freelancer based in Lahore. Its a great service. I invoice customers with small payments via SadaBiz.

Just there is a lot of cut in terms of charges and processing fee. Hope they can lower these as customer base grows.