Ladies and gentlemen, the unexpected has happened. Against all odds, the government of Pakistan has solved an important problem facing the country. They did it in the most irresponsible way imaginable, and we will be paying far too high a price for it, but in exchange, we will have solved a very real and very big problem that had been staring at the country for the past 20 years: Pakistan’s electricity generation capacity will not become dependent on imported fuel after all.

We would also like to state up front that we as a publication, and this author in particular, got this very wrong: in August 2021, we wrote that Pakistan might soon reach a tipping point where the majority of the country’s electricity generation will come from imported primary fuel sources rather than domestic ones. Not only has that not happened so far, but it seems as though it may end up not happening at all. We could not be more delighted at being wrong.

So, what are we talking about?

Pakistan’s energy problems

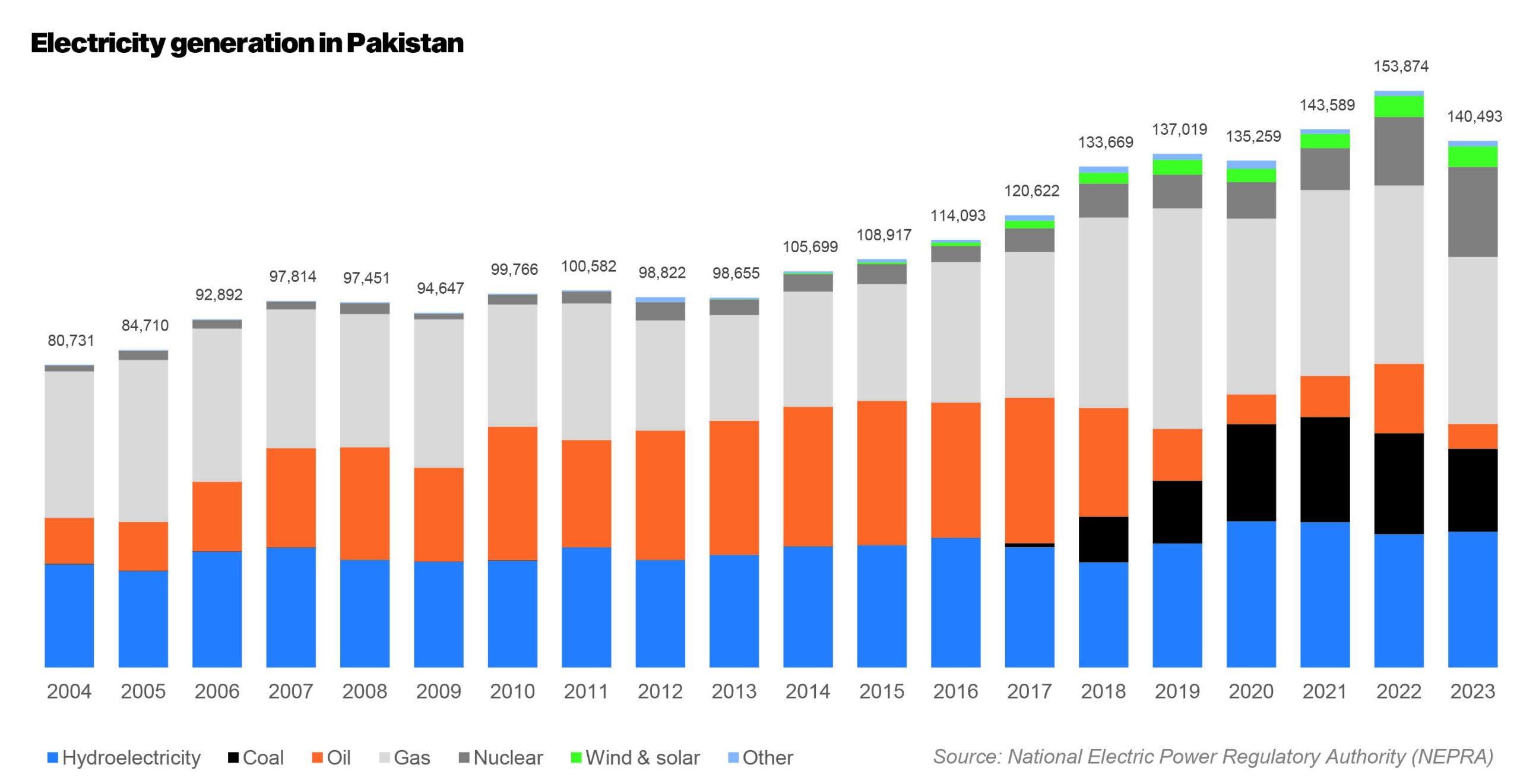

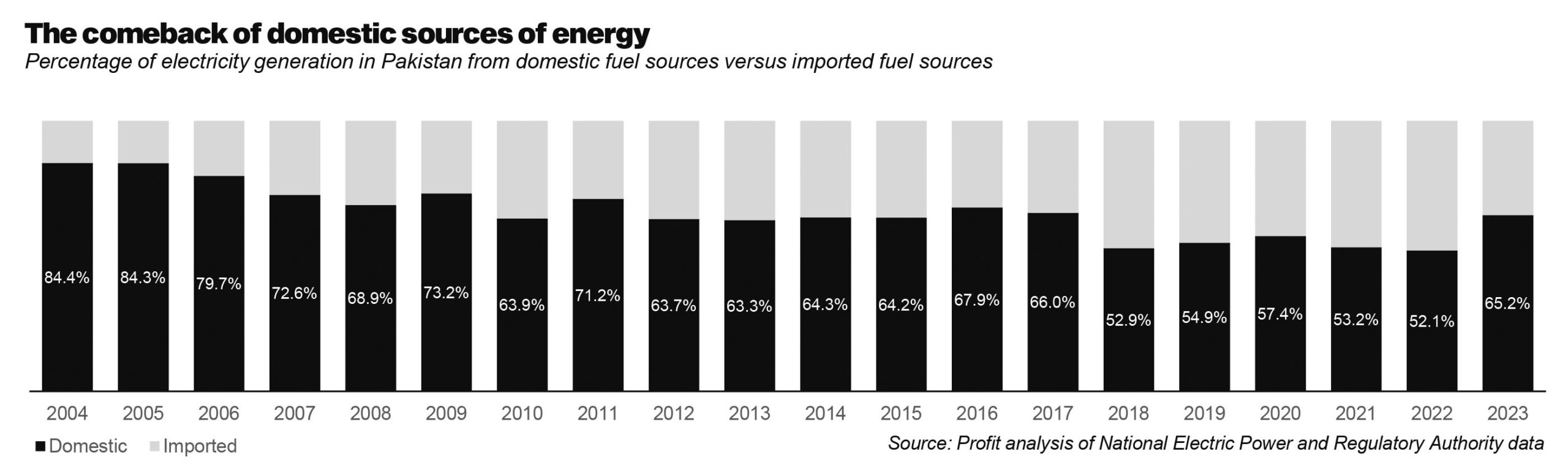

Twenty years ago, in 2004, about 84.4% of the total electricity used in Pakistan came from domestic fuel sources, primarily hydroelectricity and natural gas-fired thermal power, with that natural gas coming from domestic gas fields, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA). That meant that even as the Iraq War of 2003 drove up global oil prices, Pakistani consumers of electricity remained largely unaffected.

Even back then, however, the government of Pakistan knew we had a problem. As early as 1995, the government of Pakistan had access to estimates that suggested that Pakistan’s natural gas production was predicted to peak in 2010 and precipitously fall thereafter. Reality ended up being only slightly better: production peaked in 2012 and has since then been falling dramatically almost every single year.

That natural gas had to be replaced, but for almost 10 years, the government of Pakistan did nothing, despite the fact that in 2008, the problem got so bad that 8-12 of load shedding a day was the norm in most major Pakistani cities and electricity all but vanished in the smaller towns and villages.

It is not as though the Musharraf Administration did not know of the problem. And it is not as though they did not try something. The problem was that they were convinced that the only solution was hydroelectricity, and in 1999, when General Musharraf took power, the only dam the government of Pakistan had a feasibility study completed for was the politically controversial Kalabagh Dam.

The Musharraf Administration tried hard to push through the political opposition to Kalabagh but was unsuccessful. They then initiated feasibility studies on other dams, notably the Diamer-Bhasha dam and the Dasu dam. But it takes 10 years to even finish the feasibility study for a dam and another 10 years at least to build one, so they would never have been able to begin construction on those dams, let alone have them completed.

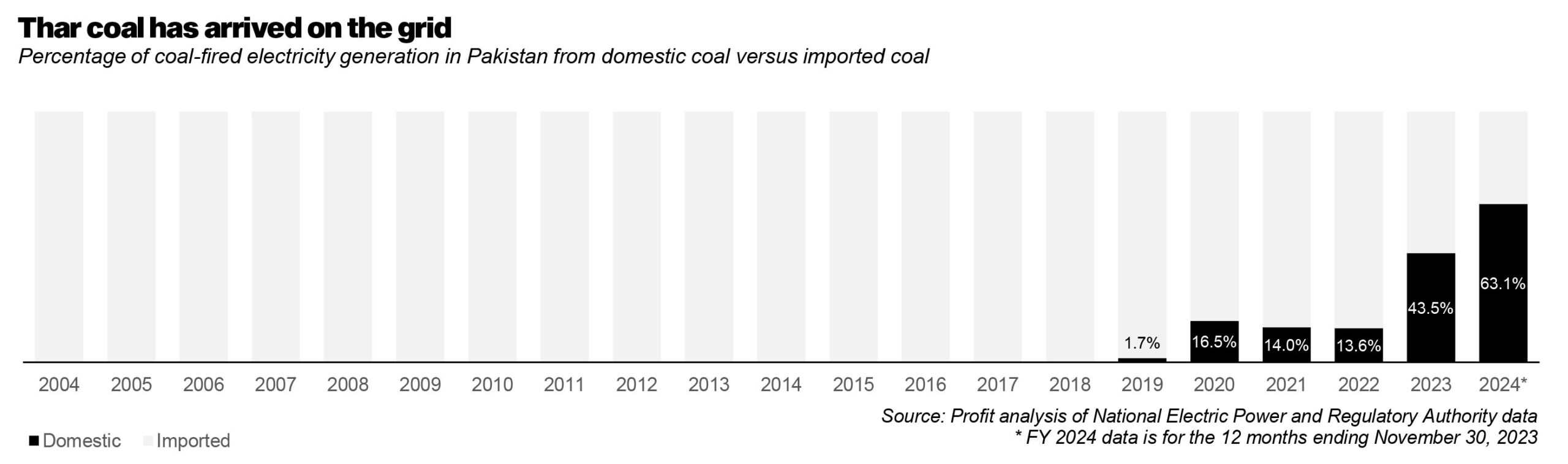

That, however, was all they tried. The Geological Survey of Pakistan has known since at least 1991 that the Thar desert has substantial coal deposits, but the Musharraf Administration all but ignored Thar. They converted part of Pakistan’s thermal power generation to natural gas, but the bulk of it – particularly the private sector power generation capacity that was rapidly becoming the country’s base load capacity – remained fired by oil.

So when the 2008 rise in oil prices came, Pakistan was uniquely positioned for a lot of pain. The government of Pakistan spent down its dollar reserves on oil subsidies to prevent the prices of both petrol and electricity from rising, but of course, the money ran out faster than they could secure more, so we had a massive fiscal and currency crisis in one go and out went General Musharraf.

The incoming Zardari Administration inherited a massive mess, but moved at an alarmingly slow pace in trying to solve the problem, and pursued far too many of the wrong solutions (remember rental power plants, anyone?). They even created hurdles for private sector players that tried to provide solutions. For years after Engro decided to create a coalmine and mine-mouth coal-fired power plant in Thar, the Sindh government – led by Zardari’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) – simply did not bother to build the road the company would need to transport equipment to and from the mine to the nearest highway.

It was the Nawaz Administration in 2013 that pursued a solution to part of the problem, and actively sought to commercialise power generation in Thar, replace the waning domestic natural gas with imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Qatar, and above all, incentivize the private sector to build lots and lots of thermal power plants, while simultaneously embarking on a massive government spending spree on increasing hydroelectric power generation.

Those policies are now bearing fruit, and after nearly a decade and a half of almost consistent decline, the domestic share of primary fuels for electricity generation in Pakistan rose substantially in fiscal year 2023, and may continue to rise in the coming few years.

What is going right: more domestic generation mix

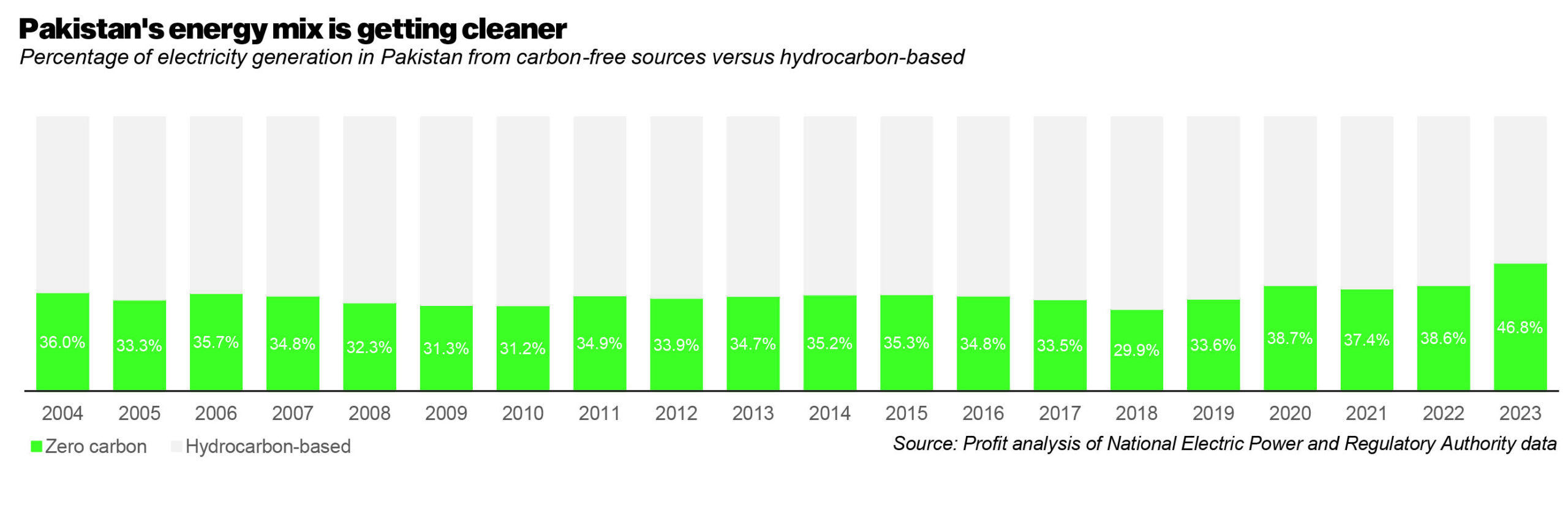

Two things are going very right with Pakistan’s electricity sector: power generation is getting reliant on more domestic fuel sources and is getting cleaner.

Let us start with the domestic vs imported mix. According to Profit’s analysis of NEPRA data, between 2007 and 2017, about one-third of Pakistan’s electricity was generated using furnace oil, nearly all of which was imported. This was a major contributor to Pakistan’s balance of payments problem during that decade: the country needed to import oil just to keep the lights on during a time when – for most of that era – oil prices hovered above $80 per barrel.

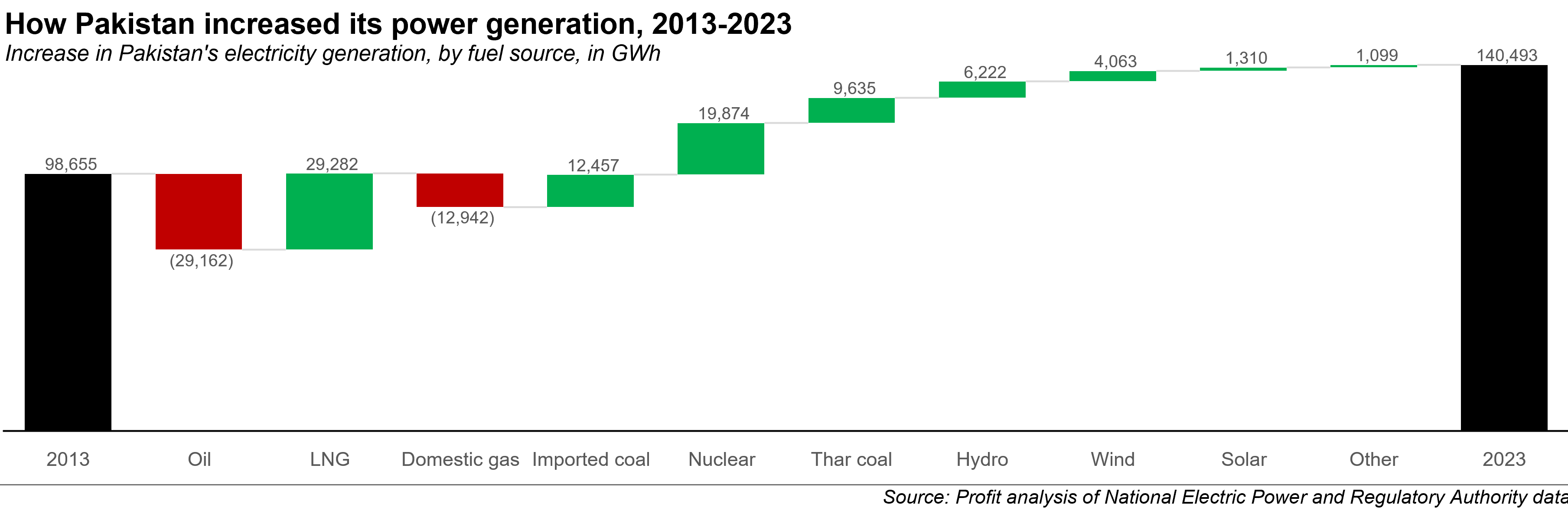

Over the past 10 years – since the Nawaz Administration began dramatically altering Pakistan’s electricity generation mix – the country has increased its power generation output by 42%, from 98,655 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in fiscal 2013 to approximately 140,493 GWh in fiscal 2023. The aggregate increase, however, is not the full story.

During that time, imported LNG replaced imported oil, and imported coal replaced the decline in natural gas. And when we say replace, we mean that almost literally. Between 2013 and 2023, electricity generation from oil-fired power plants declined by 29,162 GWh, and that generated by LNG-fired power plants went up by 29,282 GWh, an almost exact one-to-one replacement. Power plants run on domestic natural gas saw production decline by 12,942 GWh and replaced almost exactly by an increase of 12,457 GWh in imported coal-fired power production (which itself is now being replaced at least partially by Thar coal).

If those two fuel sources are seen as merely replacements for the previous fuel mix, then about half of the increase in electricity generation – nearly 20,000 out of the 42,000 GWh increase in power generation – has come from nuclear energy.

It does not get much coverage in the press, but Pakistan’s nuclear energy program is a quiet success story. As recently as 2009, Pakistan got less than 2% of its electricity from nuclear energy and now that number is above 17% of the total electricity generated in the country, largely on the back of Chinese-backed nuclear power plants at Chashma, and a substantial increase in the generation capacity at the nuclear power plant in Karachi. So important is nuclear to Pakistan’s increase in electricity generation that the net amount of nuclear energy added to the grid is about equal to the total added by Thar coal, wind, and the new hydroelectric power plants combined.

Here is how good and reliable nuclear power is: that 17% of electricity generated comes from power plants that constitute just 8.5% of the country’s installed power generation capacity. It is the only category of power generation where the actual production exceeds its share of installed capacity. Basically, the nuclear power plants got turned on once and have not been turned off since. (Strictly speaking, this is not true, but the variation in month-to-month generation of the nuclear power plants is lower than that of any other category of power plant in the country.)

That we even have this capacity is nothing short of a miracle: only 35 countries in the world even have any kind of nuclear energy program and Pakistan is one of them. We are the 18th largest producer of nuclear electricity in the world, and get a larger share of electricity from nuclear power than India does (though India generates more than twice as much in absolute terms).

But while nuclear helps explain the ability to increase power generation through domestic means, it is not the only part of the story. The other part is Thar coal, which is increasingly beginning to replace imported coal in Pakistan’s power generation mix, a trend that has become more visible over the past 12 months. December 2022 is the first month when Pakistan generated more electricity from Thar coal than imported coal.

Combine the massive increase in nuclear energy with the additions to hydroelectric power generation, and domestic coal-fired power plants, and Pakistan’s reliance on domestic sources of fuel has gone from 52.1% of electricity in fiscal 2022 to 65.2% in fiscal 2023. And the number for fiscal 2024 might end up being even higher if the trend in Thar coal replacing imported coal continues.

What is going right: cleaner energy

The other big thing that appears to be going right – especially given how vulnerable Pakistan is to climate change – is that despite the massive increase in coal-fired electricity generation, Pakistan’s electricity generation now has a higher share of zero-carbon sources than at any point in the last two decades, and quite likely even three decades.

During the fiscal year 2023, about 47% of the electricity generated in Pakistan was through zero-carbon sources, the two largest of which were hydroelectric (25.8% of the total) and nuclear (17.1%) followed by wind (2.9%) and then solar (0.93%). This is much better than 30% of electricity that was being generated by zero-carbon sources as recently as 2018.

One small thing to note about solar energy, which is getting a lot of attention among Pakistan’s upper middle class neighbourhoods owing to the popularity of rooftop solar installations in many homes. Yes, rooftop solar is increasing in scope, but it is not yet a meaningful percentage of the overall electricity supply of the country.

While NEPRA does not have an estimate of how much electricity is generated by those rooftop solar installations, it does now report how much electricity is purchased by the grid through net metering, where people with rooftop solar panels sell some of the excess electricity they generate back to the grid. That number for fiscal year 2023 for the whole country was about 280 GWh, or about 0.2% of the total electricity generated by the country.

Industry experts estimate that net metering accounts for between 20% and 40% of the total electricity generated by rooftop solar panels. If we are generous and assume that 80% of the electricity being generated by rooftop solar is being used in the homes of those who installed the panels and only 20% being sold back to the grid, we arrive at an estimate of 1,400 GWh of electricity being generated by rooftop solar panels, or about another 1% of the grid’s total power generation.

Distributed generation is not (yet) a significant threat to the grid.

What is still going wrong: theft and subsidies

Of course, fixing how much electricity can be – and is – generated by the national grid is hardly enough if that electricity is not sold and paid for by end-consumers. And that is where the Pakistani system has not improved nearly as much as it should.

Transmission and distribution losses – the proportion of electricity units that are produced but never billed because they get stolen, or lost owing to transmission over long distances – average about 17.2% in the state-owned portion of the grid that cover the whole country except Karachi, according to NEPRA’s data for fiscal 2022, the latest year for which complete data is available. And in Karachi, those losses are slightly worse at around 17.9% of total electricity generated.

Some losses are natural and the result of simple physics: wires have resistance to electric current and so some energy is lost in that resistance. In an efficient grid like the United States, that loss is around 6-7% of total electricity generated. So the fact that Pakistan’s system-wide losses exceed 17% suggests that 10-11% or more of the electricity generated in the country is stolen.

Unfortunately, the problem does not end there, because even when the utility companies are able to deliver a unit of electricity to a customer they can issue a bill to, they are not very good at collecting those bills. The state-owned portion of the grid was only able to collect about 90.5% of the amounts it billed in 2022, meaning almost 10% of the billed amount is just never paid. The privately-owned K-Electric did a bit better, leaving just 3.3% of the billed amount unpaid.

And then there are the subsidies. So much is wrong with the subsidies it is hard to even know where to begin. They are highly untargeted meaning, according to one World Bank study, approximately 90% of the benefit of those subsidies goes to the upper middle class, and not the poor, its intended recipients. They are supposed to cover part of the cost of theft – in itself a bad idea since it disincentivizes the utility companies from doing more to crack down on theft.

But worst of all, they are promised by the government but have not been paid in full for at least the last 15 years. In fiscal 2022, the government set the subsidy levels such that – by its own calculations – it would owe Rs564 billion to the electricity companies.

Those unpaid subsidies have created what is now famously called the “circular debt”. The only good thing that can be said about the circular debt – which currently stands at close to Rs2.3 trillion, according to NEPRA’s most recent disclosures in August 2023, is that the number has only risen by about Rs150 billion in the last three years.

But even that may be misleading, since the electricity circular debt is now no longer the only circular debt in Pakistan. There is now also the natural gas circular debt, which for years the government refused to even acknowledge existed. That number stands at Rs2.9 trillion.

Failure to deal with these leakages and thus creating an unreliable source of revenue for companies that do business in the energy sector means that Pakistan’s energy sector is financially inefficient: it produces expensive electricity, has too much capacity that needs to be paid for, and then does not have the means to have it all paid for by either collected bills or subsidies paid on time.

But the silver lining: it is here.

The upside of a debt binge

Ideally, we would live in a country that was run by a government that could collect enough taxes to live within its means, or at least not be fiscally irresponsible and go on a debt-fueled spending binge. We know not to expect that. We’re Pakistani. We do not have that kind of luck. The best we can hope for is the next best thing: if our government is going to go on a debt-fueled spending binge, then hopefully it will spend that money on things that will actually deliver economic benefits to the country in the long run.

And on that score, the debt binge from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has at least that virtue: we got a large increase in power generation capacity out of it. What that means is that the economy can increase substantially in size – by as much as 50% from its current levels, based on Profit’s rudimentary analysis of data from NEPRA and the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics – and it would not need to materially add to its electricity generation capacity. (Transmission and distribution continue to need investment, though.)

Electricity is expensive now, and yes, with better planning it would not have been this expensive. But in relative purchasing power terms, this may mark the high point for how expensive electricity is in Pakistan. As demand goes up, the marginal cost of producing each unit will go down. And if the planned privatization of the state-owned electricity distribution companies goes through and results in a meaningful crackdown on theft like the one executed by K-Electric, that transition may come faster still.

It may come as a surprise to most Pakistanis that the country actually already has enough electricity to begin its industrialization process. According to the economist Charlie Robertson, the level of electricity at which most countries gain the ability to start industrializing is around 300 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per capita. Pakistan’s electricity generation hit that number in 1999, during fiscal 2023, hit 582 kWh per capita, well above the level required for rapid industrialization to begin.

There are other ingredients missing which have prevented Pakistan from industrializing, namely insufficient literacy, and a low national savings rate, but those are also problems that are likely to be solved some time over the next decade (more on those two in subsequent articles).

More to the point, think of the progress we have made as a country: power outages just a few years ago happened for several hours a day every day and a large amount of mental energy had to be exerted in planning around those outages. Now, in some parts of some cities in Pakistan, a power outage comes a mild surprise: not that you do not know what it is or think of it as unusual, but usually something you are not expecting to happen.

That is a small shift, but one that could be a precursor to a much longer, sustained industrial take-off for Pakistan. But more on that later.

Comments are closed.

It’s remarkable to witness Pakistan’s government addressing a longstanding issue by averting dependence on imported fuel for electricity generation. However, the unconventional approach raises concerns about long-term consequences and sustainability.

More than the electricity itself, my concern is free electricity to a large number of WAPDA and DISCOs employees and electricity theft. I feel I am paying for all these ‘muft khoras’ and electricity thieves. What I get in return is prolonged load-shedding. Yet another concern of mine is that these excessive loadsheddings are not across the board but in areas where ordinary humans like me live.

very good article and certainly a silver lining when there is so much disappointment and hopeless situation all around.

But increasing power tariff is a huge pain for a common man and even for industry as they will not be able to compete both domestically and internationally.

Now energy problems are observed all over the world, but I believe that everything will be correct by developing our own energy resources and becoming less dependent on imports.

a good article with much information on our electricity eco-system. our successes include increasing share of domestic fuels but we must wake up on who amongst us is stealing the electricity we are paying for. we should stand up as nation against those thieves and shun them

Coal-based energy has significant and adverse impacts on climate change due to the release of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and other pollutants during its extraction, processing, and combustion. Pakistan is already affected by climate change so the coal and oil based energy must be replaced with renewable energy by making public private collaborations.

excellent article. coal energy is not green, so for now it’s good but for long term we need to invest in more nuclear and other sources of renewable energy.

Good article, I would like to know the true cost of each fuel source, think nuclear is good but expensive if you take the lifetime cost into account, e,g decommissioning

Seems like a well-reaearched article but a lot of conclusions have been made, which might or might not pan out.

Nice good information of cleaner domestic electricity of Pakistan.

useless…. Pakistan still imports gas. if they don’t ban the production of electricity from gas they aren’t getting anywhere. gas will still be needed to be imported from elsewhere

One of the steps which can be immediately taken to manage circular debt is to let go the central power purchasing. IPPs should be allowed to sell spare capacities to customers directly without CPPA involvement. This should be incetivitized for less efficient plants which are being maintained on stand-by positions just collecting capacity payments from the governments.

As per UN Tracking Report 2023, the progress on SDG 7 is Shown as:

Renewable energy(hydel+solar+wind) share in Total final energy consumption(%)= 7.2. Further it is eaborated that this share is decreasing.

Please clarify?

Informative article.