Recently, a YouTuber called Ducky Bhai was released from custody by the National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency (NCCIA). Ducky Bhai, whose real name is Saadur Rehman, had been arrested allegedly on the grounds that he had been promoting gambling and betting apps through his YouTube channel, which currently has 9.81 million subscribers. A serious charge in a serious society (at least in these matters).

Ducky Bhai was kept in custody for over three months. Upon his release, he released a video, over 50 minutes long, and which has been viewed over 15 million times. Here he alleged that he had been subjected to physical abuse by certain NICCIA officials during custody, who also defrauded him of hundreds of thousands of dollars from his Binance account.

Talking to his followers on YouTube was a way not only to present his side of the story, but also to draw attention to the harm he had suffered and urge some support which there was no shortage of. There was widespread condemnation of this treatment. YouTube, which was alleged to be the site of Ducky Bhai’s supposed crimes, also became the platform where he could highlight the inexcusable overreaches he had been subject to.

The double-edgedness of social media platforms aside, the case of Ducky Bhai illustrates the power YouTube has of reaching audiences and forming communities. Although short-form content like YouTube shorts has also taken over the platform, they are not a very good match for the longer format videos which allow for deeper interactions than the reels you barely spend half a minute on, and then scroll on to the next.

Independent YouTubers – those who are not TV or Entertainment or official channels of institutes like the PCB or the ISPR – work a lot to carefully curate and create these communities. They have a logic of their own, a community and politics to match that. But perhaps most important of all is the fact that these ecosystems allow people who don’t have much more than a smartphone and a software to edit videos to earn money from what they create. The content varies in quality, but whatever it is, more of it is being produced, and people are consuming more of it.

However, Pakistan’s relationship with YouTube – on the whole – has been fraught with state censorship which has often derailed the population’s access to the website and its contents. Despite that, the rising number of YouTube users and independent content creators in Pakistan has spawned its own economies and rapidly changed the way the platform has been viewed and used.

YouTube and Pakistan

YouTube was founded in 2005 in the United States by three former PayPal employees, Jawed Karim, Chad Hurley, and Steve Chen. As a video sharing platform in an era where the internet was rapidly becoming current, YouTube’s potential was great, and Google bought it the next year for 1.65 billion USD.

Since then, YouTube has grown and grown and never looked back. Currently, it’s the second most visited site after Google, with estimates of more than 2.5 billion active users. Over 20 billion videos have been uploaded on YouTube, with an average of 20 million being added daily to the platform. YouTube Shorts, short-video content, are averaging over 70 billion daily views. This is a lot, but that is the fact: YouTube is everywhere. In Pakistan, as well.

Yet, as YouTube in Pakistan arrived – as part of the broader web – its presence in Pakistan soon became subject to controversy. The first came with a ban on the video-sharing platform in 2008, when the government blocked access to YouTube on the pretext of the presence of content that was blasphemous, and restored it not until it had been removed. The same thing happened in 2010.

In 2012, the mechanics of this biyearly pantomime changed. Again, there was blasphemous content on the platform, this time in the form of a short film called “Innocence of Muslims”. The Pakistani government, again, as was its wont, went to YouTube, and asked for the removal of this video. This time, however, YouTube refused to entertain these concerns. Pakistan refused to entertain this refusal. And, suddenly, YouTube was no more in Pakistan.

Of course, people still found a way around with proxies and VPNs and whatnot to access this content. Censorship in a sense was no longer as absolute as it might have been in the past. Yet, the fact remains that this did bar a great many people from accessing the platform, especially in an age, and stymie the integration of this platform within local imaginaries of what internet could mean in their context, and how they could make it their own.

The impasse continued for over three years, until in 2016, YouTube launched a Pakistan-specific version of its platform. This was a thaw, which represented a reconciliation of both claims. The Pakistan government had a say in what type of content was allowed on YouTube in Pakistan, while YouTube gained its market back.

There have been occasions where the state has tried to curtail content on the website, as part of its general tendency for censorship. Earlier this year in June, the state sought to ban YouTube channels of figures critical of the government for being “anti-state,” which included charges of allegedly criticizing both state institutions and officials. This chosen band included not only the jailed ex-Prime Minister Imran Khan, but also a slew of other journalists who did little to be in the good books of the government.

But the government’s genetic tendency towards restricting material aside, the rise of Pakistan YouTube, since its reintroduction, has been meteoric. Accompanied by the increased accessibility and affordability of internet, as well as the flooding of smartphones in the local markets, where it has become increasingly commonplace for people, especially the younger generations –not an inconsiderable part of Pakistan’s population – to own one, this rise was not too surprising.

Money, Content, and Money-Content

Now, there are two major reasons why anyone would put a video up on YouTube. First, they want to show what they have produced to the world, for whatever reason. The other reason is to make money off of the first.

And the peculiar attraction of YouTube is that it allows for both. In fact, monetization was introduced quite early in YouTube’s history, allowing content creators, through the YouTube Partner Program (YPP), to earn a portion of the advertising revenue from the ads they ran on their videos. It was aimed at encouraging “original and authentic” creation, with only specific types of content being allowed to be monetized. Content which, on the other hand, doesn’t have much input from the ‘creator’ and is essentially just copying or simple collation is generally not allowed to be monetized.

To understand the way this money is handled, we must know two terms. The first is the cost per mille, or CPM, as it is commonly known. This is the price advertisers pay for 1000 impressions on their ads. The second term is rate per mille, or RPM, and this is what the YouTuber gets paid for 1000 views on their videos running the ad. In general, the RPM is 55% of the CPM, i.e., the content creator gets paid 55% of what the advertiser pays, while YouTube keeps the remaining 45%.

Running ads is by far the major way to make money from YouTube, but not the only way. One can earn money by shopping brands through links one posts, either for one’s own products, or someone else’s. It is also possible to earn money from premium subscriptions to one’s channel, which allow some subscribers access to limited, restricted content. Other features such as Super Chat, Super Stickers, and Super Thanks, allow fans to pay to have their comments or animations highlighted in the content, allowing YouTubers another way to earn off of their content.

Another thing to understand about this economy of payments is that the CPM (what advertisers pay for 1000 impressions) and, consequently RPMs (the payment content creators get for 1000 views or impressions) varies according to various factors.

The first of these is geography, of course. If you are based in the US, the CPM might be over in tens of USD. If, on the other hand, you are based in Pakistan, this can range from 0.18 to 0.69 USD, a much lower figure. Considering that what the creators get paid is just over half of that, it doesn’t appear to be too much for local content creators. Advertising budgets in countries like Pakistan aren’t staggeringly high, so this disparity makes sense.

The second major factor influencing the CPM rates is the type of content being produced. Certain niches, such as technology, educational content, and digital marketing can fetch higher rates compared to more common forms of entertainment content like music, vlogs, gaming. These latter usually bring lower payment rates for the content producers.

Another factor is the locations where the videos are being viewed. Even if the content creator is based in Pakistan, views from abroad will bring in more money than local views.

There is another determinant: how the viewers find the video. Those which YouTube users find through the search function are more lucrative than the ones which they encounter either through the ‘suggested’ or ‘browse’ features.

Similarly, YouTube videos bring in more money per 1000 views than a YouTube short, and so do the videos containing un-skippable ads.

But it is not simply a matter of gaining views and earning money. Certain conditions must be met in order for monetization to take place. Other than adhering to YouTube’s policies regarding content, one hoping to make some of that YouTube cash must meet the following conditions.

To monetize views from fan funding and certain shopping features, the channel must have at least 500 subscribers and three valid uploads in the past 90 days. On top of this, it must also have either 3000 valid public watch hours in the past year or 3 million valid public Shorts views in the past 90 days.

If one wants to earn revenue through ads – the most popular way – then one must have 1000 subscribers at least and either 4000 valid public watch hours in the past year or 10 million valid public Shorts views in the past 90 days.

Once monetization has been approved, it’s game on. A race to produce content starts, and generally the production quality improves to attract and keep the attention of bored YouTube users, whether looking for something particular, or just to spend their time.

PakistanTube

With the monetization mechanisms in place, it is no wonder that people have increasingly flocked to YouTube to make, or if it is already made, increase their reach, and put some cash in their purse.

Currently, Pakistan has over 54 million YouTube users, who are looking not only for content that is high quality, but also reflects and engages with who they are, their issues, and their real normal lives. The potential, driven by the rising population, is massive.

A recent report by Google paints a picture of the current state of the platform’s usage in the country. As of 2025, over 95,000 Pakistani channels have amassed more than 10,000 subscribers. More than 13,000 channels have over 100,000 subscribers. And, as for channels with over a million subscribers, they number upwards of a thousand.

This includes YouTube accounts for major TV channels, who of course came in to take their part in this pie which essentially has no borders. We have major news channels being livestreamed 24/7 on YouTube, perfect for older generations who can carry the news in their pocket, and blare it at full volume whenever and wherever they desire.

Similarly, major TV production houses like Hum TV and ARY Digital have also been uploading their popular soap operas on YouTube racking up over a hundred billion views, making YouTube one of their biggest sources of revenue, competing with traditional broadcasting. For Hum TV, for example, the revenue from YouTube has ranged, in recent years, from just under a fifth to around a quarter of percentage of the total revenue.

All this is well and good, but what is more remarkable is the rise of the independent YouTubers, who have quickly built niches and fandoms of their own. In a context, where creativity often means making peace with privation, this has offered them a way out.

We saw around a decade ago how YouTubers like Zaid Ali T and Shahveer Jafry made a name for themselves by producing content that was relatable for local people, and poked fun in their own manner at various aspects of the desi culture. It was mostly harmless fun, but immensely popular, considering what stage YouTube’s usage was at that time in Pakistan.

Since then the market of content has been flooded with newer, rising content-makers, who are building not only of the general trends, but also carving niches of their own.

The biggest of these is perhaps the lifestyle, vlog, and entertainment category.

In fact, the independent channel with most subscribers after the news and entertainment behemoths, falls into this category. It is called ‘Brothers Vlog’ and has 25.2 million subscribers. Yes, indeed. On top of that, it has amassed over 17 billion views.

As far as the content is concerned, it is two brothers, Madni and Mairaj, sometimes accompanied by their father, who play out different skits, try out new challenges, and document parts of their lives. The videos are transparent. Not a thought is suggested that then is not spelled out. The pace is fast. There is not a silent moment. These are designed to hook, and it appears to be working.

A notable thing about this channel is that although the channel has over 2200 videos, the videos with over a million views number a measly ten. For a channel with so many subscribers, their most popular video has been viewed a relatively low 6.9 million times.

This trend is reflected in other creators as well. Lucky Sayed, who has over 7 million subscribers, has uploaded videos that have been viewed over 2.6 billion times. However, his most-viewed video has gained 2.8 million views, and only three out of the total 1800 videos on his channel have been viewed more than a million times.

Similar is the case for many other creators. What they lose in views for a single video, they make up in numbers. At the same time, older videos keep racking up views, and leading to a situation where even if individual videos do not gather ridiculous amounts of views, the cumulative effect offsets the lack.

As for the content in these channels, it is broadly geared toward entertainment, and features the different kinds highlighted in the banner of Lucky Sayed’s channel: “Funny Video, Lesson Video, Emotional, Suspense”. In fact, the second and third categories are massive on Pakistani YouTube.

One channel, named “Moosa Tv Info” deals almost exclusively in short videos of feel-good moments made by someone else or simply caught on a camera somewhere. The channel description proclaims the channel’s purpose: “It is a way for me to spread HUMANITY, PEACE, and LOVE, and I upload inspiring videos for all those who believe in it”. You wouldn’t guess how many subscribers it has. 5 million? More. 10? 15? More. 20? Even more. 25? Close, it is 24.2 million. Yes.

Some content creators go a step further and produce and act in videos that have a moral or a social message. These include the aforementioned Lucky Sayed, and a host of other creators. One of the more interesting of these is “Bwp Production”. It doesn’t have as many subscribers as some of the ones mentioned before, but still has a substantial following of 842,000.

The production value of these is better – you can see they have invested in it. What’s interesting is that in some of their videos they have collaborated with the local police to produce skits that aim to encourage people to follow the law, speak out against any wrong they see, and be peaceable. Such videos also feature props such as a police station, police cars, apparently real policemen, and even have a short message by a police officer at the end summing up the message in the video.

The actors in such videos are people, often estranged from the urban metropoles, either the channel owner, their friends, families, or even what appear to be random strangers, not one of them even close to being called a celebrity. There is a quaint charm to this cast and a local flavour that accounts, perhaps, for their popularity. These are real people, who because they aren’t well-versed in the sophistications of a performance art school, feel unbound by the elementary scripts, and perhaps remind people of something vital that has been lost from our TV screens.

There are also YouTube celebrities like Ducky Bhai (9.82 million subscribers) and Shahveer Jafry (3.88 million subscribers), famous for the pranks they run, though they are also diversifying their content to catch up with the changing preferences of the Pakistani market. Shifting to more ‘challenge’ or ‘situational’ scenarios, sometimes vlogging parts of their lives and careers, these channels show how creators are modifying their content according to the changes in the local taste, brought about by access to international creators and a desire to produce something like that with a local flavour.

Diverse Topics, Many Channels:

There are other categories as well. Sports influencers, sometimes ex-cricketers like Shoaib Akhtar and Shahid Afridi, or people close to international cricketers such as Faisal Azam (the brother of Babar Azam) have strong followings both locally and internationally. Another category is videos of local tape-ball tournaments (which have made celebrities of cricketers such as Taimoor Mirza, a local legend). There are multiple channels catering to this niche with millions of followers combined. An emerging subcategory is of GoPro videos of hardball matches, which take viewers right in the middle of action.

Then there are podcasts, of course. Channels like Shahzad Ghias Sheikh’s “The Pakistan Experience” (331 thousand subscribers) and Muzammil Hasan’s “TBT Podcast” (367 thousand subscribers) provide local versions of what has become a global phenomenon in the personal entertainment industry, talking about local issues and placing them in local contexts, or just simply yapping and chattering the time away. The range of conversation is wide: politics, history, cricket, economics, entertainment, literature, religion, and so on. The conversations, as shown by their popularity, evidently have a market of listeners, hungry to enrich their conceptions of their own realities, or simply to while away a boring stretch of time.

There are also YouTubers, such as Engineer Muhammad Ali Mirza (3.16 million subscribers) and Tariq Jameel (8.83 million) who speak about religion. They have massive followings, though as the recent blasphemy case against Engineer Mirza shows, it is a slippery category to really make one’s name in. One is never too far away from a controversy, which could have real life consequences.

Different in category though similar in kind, is the case of political YouTubers. Often fiercely partisan, these often become pawns in broader political games. Criticising the wrong sort can get you disappeared. It is not to say that these political commentators don’t have any influence; rather, these are also celebrities of their own, with people attached to some as they might be to anyone, and often wield real street power. Yet, they are only as strong as the reach of their content, and the state holds the jugular of this reach.

A category of finance and investment influencers have also been quietly making a mark on Pakistan’s YouTube landscape. The two prominent names here – Mashal Khan (70 thousand subscribers) and Abdul Rehman Najam (88 thousand subscribers) don’t have massive followings yet, though people, considering the state of financial literacy in Pakistan, are rapidly getting interested in this sort. A previous story by Profit (https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2025/09/29/can-pakistans-rising-corp-of-investment-influencers-do-the-trick/) covered this crop of influencers, and its potential to change how people thought about money in Pakistan’s context.

Female creators are also claiming their own in this growing market. Catering mostly to interests of the fairer sex which find not a voice elsewhere, a rising crop of influencers have been making their mark. Some of them fall in the category of lifestyle influencers, who simply vlog parts of their lives – there’s no shortage of that.

On the other hand, there are some which fill in a genuine void. One of these is “Humna’s Gram” (435 thousand subscribers), whose videos feature her going to local markets and trying to find out cheaper alternatives to the wildly expensive designer clothes, and offering advice on how to build a wardrobe. Others like “Glow Up With Mahnoor” (353 thousand subscribers) offer makeup tutorials and skincare advice, tailored to the contingencies of local skin and weather as well as taking into account the availability and accessibility of products in Pakistani markets.

Food influencers have made a space for themselves as well. Other than the major food bloggers who review food joints such as Rana Hamza Saif (1.59 million subscribers), there are chefs as well, offering in depth recipes for the delicacies of South Asian food. Two major names in this are Chef Afzaal Arshad’s “Kun Foods” (3.26 million subscribers) and Chef Amna’s “Kitchen With Amna” (4.4 million subscribers).

Another type of food niche is made up of content creators who are highlighting types of cuisine often missing from the urban consciousness, though versions of these have of course seeped into the cosmopolitan pantry. One of these is called “Village Food Secrets” (4.37 million subscribers) where food recipes as carried out in villages are presented, giving viewers a chance to gain knowledge of a way of living that is gradually vanishing.

These are some of the major types of content being produced and consumed on Pakistani YouTube. There are others too. Travel focused content, though mostly dominated by foreign vloggers who come to Pakistan to comment on the population’s generosity also has local players like “WildLens” by Abrar,” a channel with 2.17 million subscibers. There is a charming cast of wildlife focused content-makers such as “Wild Rush” (211 thousand subscibers) and “Wildlife with Dr. Waseem” wih (298 thousand subscribers), who explore local wildlife and educate people regarding the forms of life that surround them and populate the same lands they live in.

Rise of Long Form Content and Smart TVs:

One of the major factors in the increase in YouTube viewership is, of course, increased access to internet and devices where one can access it. There are smartphones which provide portable access, but it is particularly suited to shorter durations of viewing. Smart TVs (or connected TVs) allow for easier, more communal viewing of longer videos. There’s nothing like bigger screens for bigger content.

Smart TVs, also known as connected TVs (CTV), are televisions with integrated internet, allowing users to stream music and videos, view photos and essentially browse the internet on their television set.

While these TVs grant viewers access to streaming services and other ways of accessing content, YouTube remains one of the top used apps on TVs. This is, first of all, because YouTube is free (unless you’re paying for the premium plan). At the same time, the fact that the kinds of stuff people used to watch on pre-internet TVs (news, soap operas, etc) can now be viewed on YouTube, along with newer types of content referred to above, means most of what you need can be found here. One, in many cases, doesn’t even need cable, since YouTube is like a mega app for whatever one wants to watch.

A recent report by the Wall Street Journal covering what Americans watched on their TVs reveals that YouTube became in 2025 the most-watched video provider in the country. At the same time, the report mentions that people were watching YouTube on their TVs more than on any other type of device. As YouTube keeps improving its TV app, influencers are pitching in producing longer, more family-friendly content.

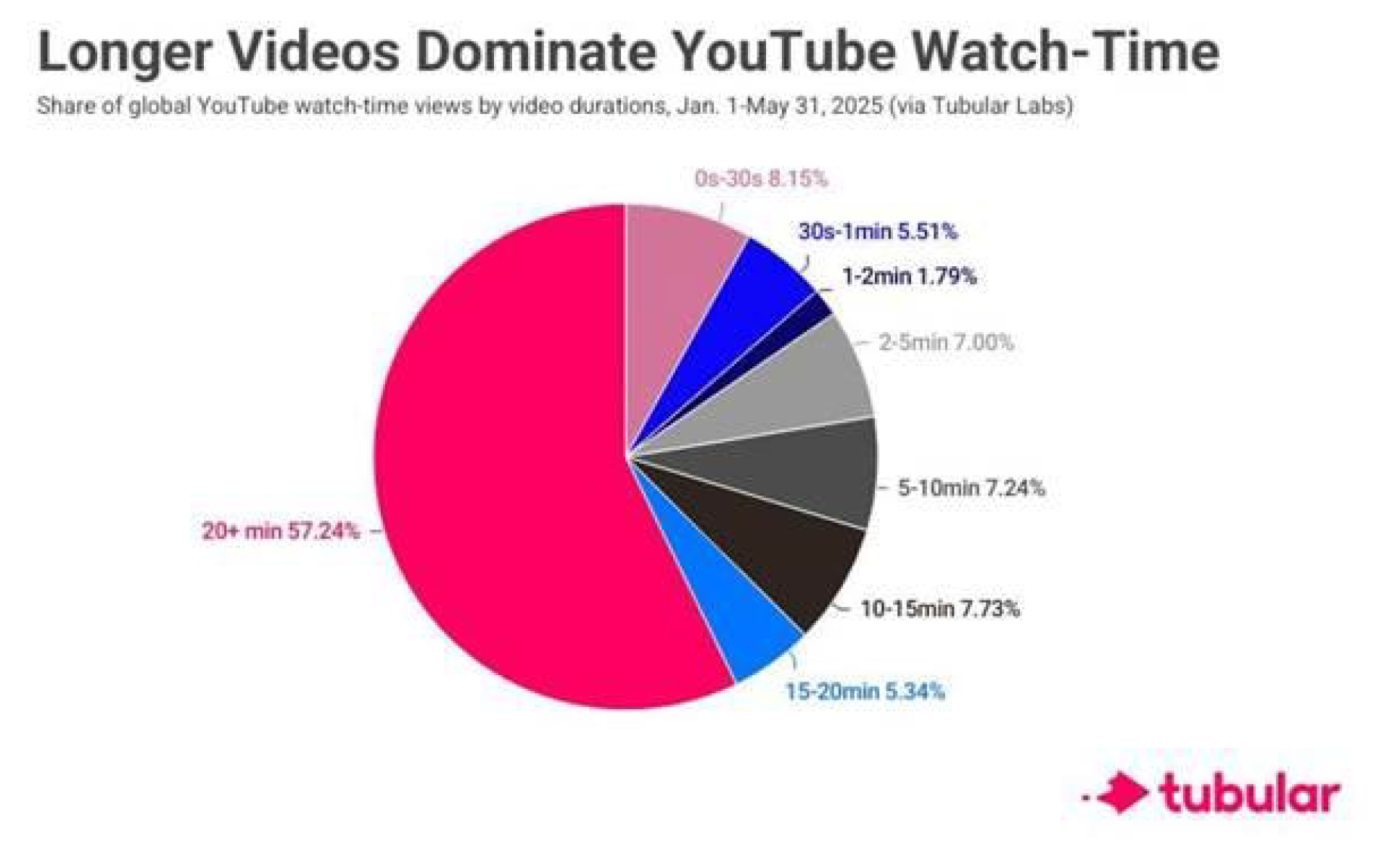

A study by Tubular Labs also analysed the length of YouTube videos and their correlation with viewing time. It revealed that longer videos made up the greatest percentage of the total time spent on YouTube, with videos over 20 minutes long making up 57% of the total watch time.

Longer videos also have an added advantage for content creators, in that YouTube allows for the insertion of multiple ads into videos which are over 8 minutes long. More ads mean more impressions mean more money potentially for the content creators.

One form of longer content that has been becoming popular is gameshow type content, which often involves a lot of money. People – sometimes regular, sometimes masters of their craft, sometimes both against each other – are put into situations that pit them against one another. The winner gets a big prize. The viewers vicariously share in the celebration.

The undoubted king of this sort of content is MrBeast, the most followed YouTuber with over 457 million subscribers. Staggeringly popular, the 933 videos he has uploaded on his channel have garnered over 105 billion views combined. Mostly these videos are productions covering a challenge (“Last to Leave Circle Wins $500,000” or “50 YouTubers fight for $1,000,000”, etc).

The videos certainly are on the longer side, usually between 10 and 20 minutes long, sometimes even longer: a duration that is on the sweet side – one episode isn’t too short, can stand on its own, can even last you the duration of your mean, and if there’s a desire for more it can be satisfied without falling into an hour-long ditch, as you might with many TV episodes. And, as mentioned, they allow the content creator to make more money by running in more ads.

This trend of content is already gaining a foothold in Pakistan, and might point to the changing preferences of Pakistani audience. A local content creator going by the name of “Zalmi” produces content modelled on MrBeast, and has even collaborated with him on multiple videos, trying to complete challenges MrBeast has set, going to visit his production set, and so on. Zalmi has over 3.92 million subscribers and his 221 videos have collectively been viewed over 881 million times.

What is noteworthy about these videos (mostly) of two brothers is that they bring in a lot of views. It is quite likely that the number of videos they have that have amassed over a million views, which currently stands at 156, far outstrips the number by any other Pakistani YouTube content creator. There is certainly a big market for this type of content, and other YouTubers like Shahveer Jafry are also branching into similar sort of content.

At the same time, the rise in the spread of smart TVs in Pakistan has aided the creation and popularity of such content, not to mention the myriad TV channels who now air their content directly on YouTube in addition to the traditional broadcast streams.

The number of smart TVs in Pakistan continues to rise, and the manufacturers and importers are keen to keep a steady supply of these TVs.

Earlier this year, Pakistan Electron Limited (PEL) announced a strategic partnership with Panasonic “to introduce premium smart LED TVs and display solutions to the local market”. The Chinese tech company Xiaomi, which it appears is on a mission to produce every type of consumer electronic device, also entered a partnership this year with Air Link Communications to locally assemble its line of smart TVs. Xiaomi, through its wholly owned subsidiary, Selected Technologies, is also seeking to expand its reach in the Pakistani market.

At the same time, already present Chinese brands like TCL and Haier continue to dominate the local market, accounting combined for 62% of the total market in 2024, TCL accounting for 44%, while Haier making up 18%. Local players like Eco Star and PEL account for most of the rest.

With the increased popularity of such TV sets, and trends in other countries which point to YouTube’s popularity on these devices, it would not be a stretch to say that YouTube might become a key focal point in the evolution of Pakistan’s entertainment landscape. In fact, it might be argued that it is already halfway there – as shown by the popularity of TV channel content on the website.

Where its greatest potential probably lies is in allowing local content creators to exercise their creativity and encouraging them to make money from what they produce. The quality of the content doesn’t matter at this stage. As people aim to both bring their real lives in a bid to make more ‘relatable’ content, as resources to improve production quality become more accessible, as more people start using YouTube locally demanding whatever content they might have come to prefer, it would help steer the course the content creators will choose to make.

Yet, with the occasional government snatch of censorship, it remains to be seen, how well it encouraged – or discourages – this one way for people to tell stories of who they are, where they live, and what they believe in.